Manga as Culture: Encountering expressions beyond borders

Manga enjoys international recognition as a Japanese popular cultural form. The Japan International Manga Award was launched 15 years ago to promote cultural diplomacy through manga. Manga artist Satonaka Machiko is a prominent figure in the world of manga and has been involved in the Award since its inception. Here, she speaks about the significance of the Award and her vision for its future.

Satonaka Machiko, manga artist

Interview by Nakamura Kiichiro, editor-in-chief, Gaiko (Diplomacy)

–– FY2021 marked the fifteenth anniversary of the International Manga Award, established in 2007 and renamed the Japan International Manga Award in 2016. Satonaka has been a member of the Selection Committee of the Award since its inception and has served as Chairperson since 2009.

Satonaka Machiko

Satonaka Machiko: The Award originated in a statement in 2006 by then Foreign Minister Aso Taro expressing a desire to create an international manga award in Japan. However, when it came to making it happen, ministry officials were feeling their way in the dark. At a loss as to how to proceed, a ministry official coordinating the Award initiative approached me for guidance. Thinking it would be a good opportunity to promote Japanese manga culture overseas, I agreed to be a judge, albeit with some apprehension about what lay ahead. I remember how right from the word go, we set about establishing the method of soliciting applications and the judging criteria, and selecting judges, in preparation for the launch. And we had a hard time managing within the tight budget (laughs).

–– The world had begun to take notice of Japanese manga.

Satonaka: In terms of the global scene, until then there had been two main types of comics. One was American comics, which were produced through a complete division of labor so that consistency in the material could be maintained even if a different author was used. The other was bande dessinées that took the form of pictures with dialogue, mainly produced in French-speaking countries. Japanese manga differ from these types of comics in that a single artist handles all genres and themes and is given a totally free rein in terms of ideas for story development, scene composition, and character creation. Having developed in this unique way, Japanese comics gradually attracted international attention, and before long Japan had become the world leader in manga. I thought it would carry great weight if Japan, as part of its cultural diplomacy, were to publicly honor the works of creators around the world who share an affinity with manga.

Japan International Manga Award

In 2007, then Foreign Minister Aso Taro established the International Manga Award as part of Japan’s cultural diplomacy, saying,

“I would like for Japan, as the origin of manga, to award to the standard-bearers appearing in the world of manga all around the globe a prize which carries real authority-the equivalent of a Nobel prize in manga.” The best cartoon from the entries submitted by manga artists overseas will receive the Gold Award and three distinguished works will receive the Silver Award. The Japan Foundation [Executive Committee member of the Award] will invite award recipients to Japan for about ten days. The participants will pay courtesy calls on Japanese cartoonists, publishing companies and others.

–– The screening process must surely be a challenge.

Satonaka: Back then, the Japanese embassies and consulates and the Japan Foundation helped to publicize the Award in their respective countries and accept entries, mailing the originals or copies of the works to us. Thanks to their cooperation, for the first Award we received 146 entries from 26 countries and regions.

It was a really hectic time. In the first round of judging I had to do a preliminary reading of all the entries. Since I don’t know any foreign languages I wanted to ask the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to provide me with at least literal translations. However, I was told they couldn’t spare the time or manpower at that stage, so I had no choice but to skim through the original works. While I wasn’t able to read the stories in their entirety, I could get a sense of the quality of the works from the flow of the panels, artistic sense, and so forth. I boldly whittled the entries down to a dozen or so shortlisted finalists, all of which were accepted. Then with the help of the other judges, I chose the best cartoon (Gold Award) and three distinguished works (Silver Award). Given all the hard work I had put in, I asked the foreign minister Aso to attend the Award Ceremony. He accepted my request, and since then, successive ministers have attended the ceremony. Award winners were invited to Japan for around ten days to network with Japanese manga artists, publishing companies, and others in the industry. Currently, this takes place online because of COVID-19 but we hope to get the winners over to Japan once the pandemic has been contained.

Diverse depictions of the struggles of young people across the world

––The Japan International Manga Award has gradually achieved recognition.

Satonaka: The following year, the second Award received 368 entries from 46 countries and regions. Since then, the number of entries has fluctuated from year to year, but this year’s 15th Award received 484 entries from 76 countries and regions.

I am pleased to report that both the winners and shortlisted finalists were delighted with the final selection. It’s not uncommon for the winning entries to be featured in the local news in their respective home countries, or for the winners to receive national awards from their governments. It was a thrilling reminder of how the young culture of manga that evolved uniquely in Japan is now accepted without question as a globally recognized form of expression.

Minister Aso wanted to make the Award the “Nobel Prize of Manga.” The reason Japan is able to give outstanding entries the “seal of approval” is because demand for the Japanese cultural product of manga has arisen spontaneously outside Japan and spread across the world rather than being promoted by the Japanese government. Having their work recognized in Japan means a great deal to the award winners in terms of their careers. In this respect, I think the Japan International Manga Award is a worthwhile project, not only in terms of the weight the award itself carries, but also in terms of cost-effectiveness.

–– In December 2021, the winners of the 15th Award were announced.

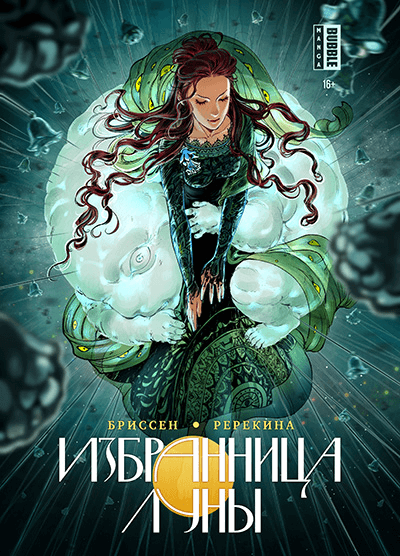

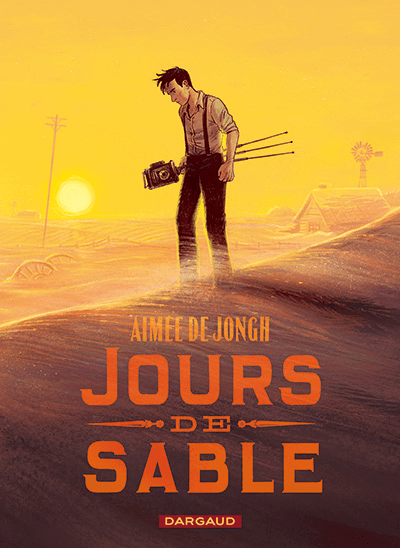

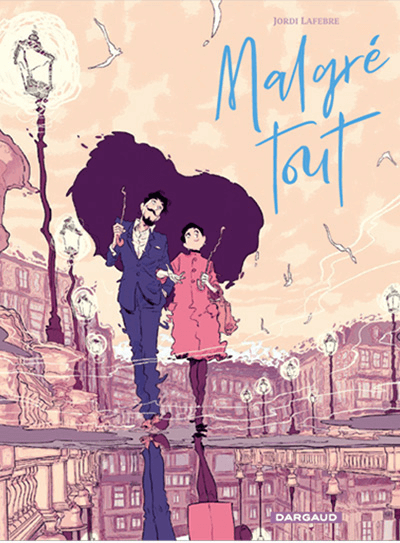

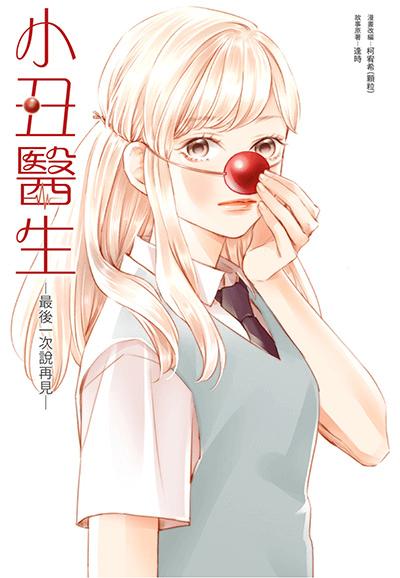

Satonaka: The Gold Award went to Aimée de Jongh (Netherlands) for Days of sand, and the Silver Award went to artist Nataliia Rerekina (Ukraine) and story writer Gilbert Brissen (Ukraine) for Moonchosen; Jordi Lafebre (Spain) for Always never, and artist Cory (Taiwan) and story writer Feng Shi for CliniClowns: last goodbye. The Gold Award winner, Days of sand, was selected for its high level of accomplishment, notably in terms of its superb composition and skillful portrayal of emotions. Excerpts of the winning entries will be available for viewing on the Japan International Manga Award section on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website.

|

Gold Award: Days of sand Artist: Aimée de Jongh (Netherlands) |

|

Silver Award: Moonchosen |

Silver Award: Always never Silver Award: Always never©Dargaud Benelux 2020 ©2022 LAFEBRE – DARGAUD BENELUX(Dargaud Lombard s.a.) Artist: Jordi Lafebre(Spain) |

Silver Award: CliniClowns: last goodbye Silver Award: CliniClowns: last goodbyeCliniClowns: last goodbye ©柯宥希/MirrorFiction Inc. All rights reserved. Artist: 顆粒 (Cory) (Taiwan) Story Writer: 逢時 (Taiwan) |

All works from the website of Japan International Manga Award (https://www.manga-award.mofa.go.jp/en/prize/15th/index.html) |

||

–– Have you noticed any changes in the works over the 15 years you have been judging the entries?

Satonaka: Most of the entries come from the younger generation. Some works strongly reflect the cultural and social backgrounds of the entrants. But a considerable number are coming-of-age dramas featuring Japanese high school students and other young people. There are also historical works. If you think about it, shojo manga aimed at teenage girls have long been set in Paris and New York. Those manga artists didn’t have any particular experience of living in those places, but felt they knew them from books or movies. When travel overseas became widely affordable, they went overseas to check out those places for themselves. Personally, it was only then that I learned that in Paris you have to pay at the time of ordering in cafes and that most train stations have no ticket gates (laughs). Today, with access to the internet, I’m amazed at just how accurately information about Japan is portrayed, even overseas.

To digress for a moment, when I read the entries, I feel that regardless of the setting, the mental anguish of the mostly young people depicted surrounding friendships at school, family relationships, worries about love, work, and the future, and so on are deeply universal. Young people with limited experience of the world bottling up their feelings and suffering about things that from an adult perspective are considered not worth worrying about is a sadly universal state of affairs. However, the importance of human relationships and ties is a constant. Cultural and artistic endeavors are the expression of human empathy and human emotion in response to issues such as these. Manga is a dramatic expression that reflects the creator’s personality and ideas without need for sets or makeup as in movies or plays. Rather, the creator depicts the world he or she wants to portray by means of the situations and characters that are easiest for them to express. The reader just has to be able to enter that world. So even when I’m judging works set in a different country or a different time period I haven’t noticed much change.

From award-winning works to best-sellers

–– Did the COVID-19 pandemic have an impact?

Satonaka: The application format changed significantly. Online applications have increased since 2020 when we started accepting them in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. I assume the online application format has made the Award more accessible for those who want to take on the challenge. In terms of how entries are produced, there has not been much change. The act of drawing or reading a work can basically be done by one person, and this is all the more the case in a situation where production and distribution are increasingly online.

As for the content of the entries, the essential impact is yet to emerge. We will never really know until the children who are going through adolescence and puberty right now become adults.

–– What are your hopes for the Japan International Manga Award in the future?

Satonaka: I would be happy if we could bring about a situation where having a manga career in Japan is regarded as a sign of excellence and a dream for creators around the world to aspire to, just as young people who play basketball or baseball aspire to play in the professional leagues in the United States. It would be wonderful if the Japan International Manga Award could be a gateway to achieving this dream. So we would like to see some of the award-winning works published in Japan and become bestsellers. Unfortunately, however, this has yet to happen. Some individual works have been digitally distributed, but without a certain volume their impact is limited. In this sense, we need to explore various possibilities for distribution and sales, such as promoting “award-winning works” of the Japan International Manga Award as a single volume. This is in fact one of our aims in inviting editors from publishing companies to participate in the screening process. While giving too much prominence to economic incentives may not be desirable, it is undoubtedly a motivating factor and I would like it to be taken into account in our vision for the future of the Award.

Translated from “Bunka toshiteno manga, kokkyo wo koeta hyogen tono deai: Nihon kokusai manga-sho 15 kai no ayumi wo furikaeru (Manga as culture, manga as a diplomatic tool: Looking back at the 15 years of the Japan International Manga Award), Vol. 71 Jan./Feb. 2021, pp. 128-132. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [March 2022]

Keywords

- Satonaka Machiko

- Japan International Manga Award

- manga

- Foreign Minister Aso Taro

- Aimée de Jongh

- Days of sand

- Nataliia Rerekina

- Gilbert Brissen

- Moonchosen

- Jordi Lafebre

- Always never

- Cory

- Feng Shi

- CliniClowns: last goodbye

- coming-of-age dramas

- shojo manga

- COVID-19