The Future of Japan’s Trade Strategy: Avoid Protectionism in the Name of Security

“Considering past efforts to promote globalization by concluding FTAs, we should refrain from arbitrarily promoting protectionism and anti-globalization under the guise of security.”

Photo: HIT1912/PIXTA

Yamanouchi Kenta, Associate Professor, Kagawa University

Key points

- Japan’s FTA networks are nearing completion

- The weaker the relationship with the partner country, the greater the effectiveness of the FTA

- Diversification of supply chains through active internationalization

Prof. Yamanouchi Kenta

Some believe that trade policy is at a turning point. The government is working on toughening supply chains for semiconductors and other products and has been implementing a project to encourage their return to Japan since 2020. Furthermore, the launch of the “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework” (IPEF), a new economic zone initiative centered on the United States, was announced in May 2022. Recently, some policies that are seemingly protectionist have appeared in Japan as well.

On the other hand, Japan has concluded a series of region-wide FTAs and other agreements in recent years, and the FTA networks covering supply chains are generally nearing completion. In discussing future globalization, this paper evaluates Japan’s trade policy in the 21st century and provides implications for policy based on economic security.

In the 21st century, the focus of trade liberalization shifted from multilateral negotiations at the WTO to bilateral and regional FTA negotiations. Japan also concluded agreements with ASEAN and Latin American countries, but most of them were with the top 6 to 30 countries in terms of trade value from a Japanese standpoint, so there was a reluctance to engage in full-fledged trade liberalization. Of the 15 agreements that had come into force by 2016, only the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with ASEAN is a multilateral agreement.

In the 2010s, China competed with the United States for hegemony in the Asia-Pacific, with negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement led by the United States and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement in East Asia, where China exercises great influence, proceeding in parallel. As a result, region-wide FTAs and other agreements have come into effect one after another with Japan since the end of 2018. The TPP, from which the United States withdrew, entered into force in December 2018 as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the EPA with the EU came into force in February 2019 as the Japan-EU EPA. Furthermore, the US-Japan Trade Agreement (USJTA) came into force in January 2020, along with the RCEP Agreement in January 2022.

Trade value in the first half of 2022 was about 100 trillion yen including exports and imports, of which trade value with countries that have signed FTAs was about 77 trillion yen, accounting for nearly 80%. This ratio is higher than that of the United States and the EU (excluding intra-regional trade), which do not have FTAs with China. Although there are issues with the agreements’ content, Japan’s FTA networks are very close to completion. Excepting resource-rich countries, Taiwan and Hong Kong are the only major trading partners that have not signed FTAs.

So, have FTAs really played a role in promoting globalization and expanding trade so far? Recent studies have shown that FTAs generally have a heterogeneous impact on trade value, with many agreements not being so effective.

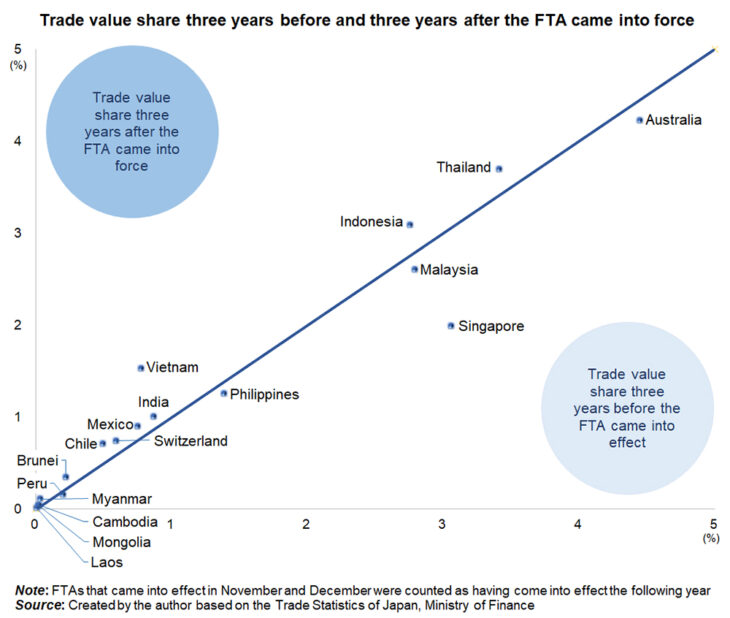

The figure shows trade with countries where FTAs came into force before 2016 with a horizontal axis showing three years before coming into force and a vertical axis showing three years after. Since trade value fluctuates considerably from year to year depending on economic trends and other factors, the method used here is rough but still illustrates trade as shares of total foreign trade value.

Many points in the figure are above the diagonal, suggesting that FTAs have contributed to trade expansion. In the past, I conducted an analysis that also took into account the economic situation of the partner country, which made it clear that about half of FTAs had the effect of increasing trade value.

Looking at it by partner country, trade value with low-income ASEAN countries such as Vietnam has increased significantly since the FTA came into effect. As such, it is thought that FTAs contribute to strengthening relations with countries with which economic relations were relatively weak before the conclusion of the agreement. On the other hand, trade value with Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, and other such countries did not increase since the FTA came into force.

There are several possible causes, but research conducted by Hayakawa Kazunobu, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) and Baek Youngmin, lecturer at Fukuyama University, has found that Japanese FTAs may have increased overseas production through foreign direct investments rather than trade.

In a joint study conducted by myself and others using detailed product-specific data, we estimated that Japanese FTAs increased the export value of taxable goods to signatory countries by about 30% and the import value of taxable goods from signatory countries by about 60%. In particular, the effect of FTAs was significant for products that had been strictly protected, but the effect of FTAs was limited for products with strict rules of origin.

Recent region-wide FTAs may have had a limited impact on Japanese trade, as they were concluded with countries that have engaged in active trade for a long time or that already had bilateral FTAs. Japan’s trade amount fluctuates with trillions of yen every year, but the trade value share with TPP signatories has hardly changed from around 12% when comparing pre-TPP with the present. The same is true for the Japan-EU EPA as well as USJTA and RCEP, which have all had limited direct trade effects.

It may be somewhat one-sided to consider the results of region-wide FTAs only in terms of trade value, but it must be said that there are no clear effects at this point. On the other hand, one of the main objectives of region-wide FTAs is to create international rules, which requires long-term commitment.

We have discussed changes in trade policy and its impact on trade, but how should policies based on economic security proceed in the future? Firstly, I would like to consider the impact of tariff policy, which cannot be ignored. Sufficient correlation has been found between tariff reduction and trade value increase. However, with the exception of some agricultural products, Japanese tariff rates are already low, leaving little room for additional reductions.

Furthermore, of the 14 countries that have pledged to join the IPEF, Fiji is the only one with which Japan has not signed an FTA. Tariff cooperation is not envisaged for the IPEF, but even if tariff reduction were included, the benefits to Japan would not be significant. On the other hand, if tariffs were raised for reasons of security, we should be prepared for corresponding impact along with retaliation from the other country.

Considering past efforts to promote globalization by concluding FTAs, we should refrain from arbitrarily promoting protectionism and anti-globalization under the guise of security. If avoiding dependence on China is an important security goal, it would be better to actively promote globalization and diversify supply chains.

In fact, some subsidy businesses are implemented with the aim of promoting supplier diversification. Yet this should be implemented in conjunction with tariff policy and not solely as subsidies. Specifically, conceivable policies include lowering most-favored-nation tariff rates and concluding new FTAs. It would be especially good to explore new region-wide FTAs involving developing countries with which strong relationships have not been built so far. By demonstrating to the world that we are promoting globalization, great political benefits are also possible if we can demonstrate our worth as a middle power.

Security concerns do not mean that policies to secure domestic production bases of a certain size are without legitimacy. However, considering Japan’s current situation, where the unemployment rate remains at a low level due to the declining birthrate and aging population, a large-scale return of the manufacturing industry to Japan is not realistic, and there is little meaning in actively promoting it. Labor is a scarce resource, so it should mainly be utilized by companies and industries with high labor productivity. We cannot afford to have uncompetitive companies and industries waste precious resources, at least not in Japan today.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 19 October 2022 under the title, “Nihon no Tsusho senryaku no kongo: Anpo meimoku no hogoshugi sakeyo (The Future of Japan’s Trade Strategy: Avoid Protectionism in the Name of Security).” The Nikkei, 19 October 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Yamanouchi Kenta

- Kagawa University

- trade

- trade policy

- free trade agreements

- FTA

- protectionism

- security

- IPEF

- EPA

- TPP

- CPTPP

- RCEP

- JUSTA

- trade value share

- overseas production

- foreign direct investment