Perspectives on Countermeasures Against the Declining Birthrate: The Real Issue Is Preventing Lost Income for Women

“In the last 50 years, the decline in the number of births has been pretty consistent, but there was a further rapid decline caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. […] We are in a state where unprecedented countermeasures against the declining birthrate are required …”

Photo: Gestalt / PIXTA

Suzuki Wataru, Professor, Gakushuin University

Key points

- The effects of cash payments and in-kind assistance are unclear

- Re-examining preferences towards stay-at-home mothers and Japanese employment practices

- All residents should pay for child insurance to secure financial resources

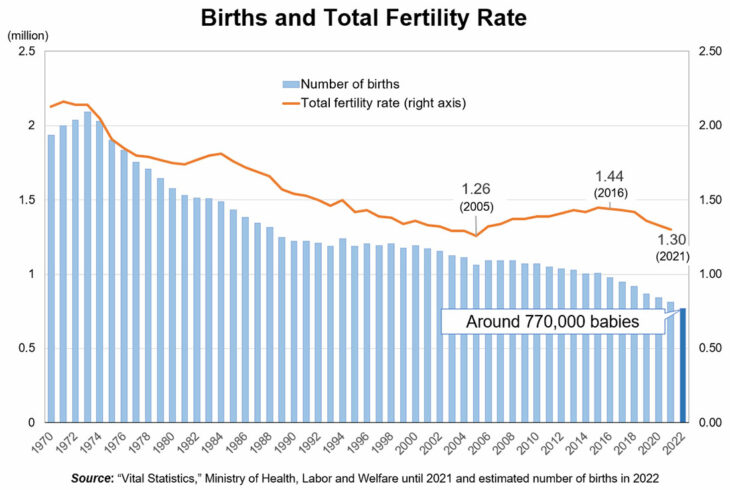

According to the flash report on Vital Statistics released at the end of February 2023, the number of births in 2022 was 799,000, the first time it has ever dropped below 800,000. This includes foreign nationals living in Japan and Japanese nationals living abroad, with an estimated 770,000 or so births among Japanese nationals living in Japan in confirmed reports. (see graph)

In the last 50 years, the decline in the number of births has been pretty consistent, but there was a further rapid decline caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is concerning that even the recovered total fertility rate has started to decline. We are in a state where unprecedented countermeasures against the declining birthrate are required, and these countermeasures should be divided into two categories for consideration: the declining birthrate that has progressed as a medium- to long-term trend, and the declining birthrate that has progressed due to the pandemic. In short, a solution for the former is difficult to find, but countermeasures are still possible for the latter.

First, the most prominent cause for the COVID-related downturn in the birthrate is the decline in the marriage rate. The average marriage rate between 2015 and 2019 was 4.9 per 1,000 people, but it plunged to 4.3 in 2022, 4.1 in 2021, and 4.2 in 2022 (preliminary report). Japan has a culture that makes it difficult to have a child without being married, so the decline in the marriage rate is a serious problem.

We can also confirm the status of married women in their 20s and early 30s abstaining from childbirth. What is concerning is the fact that attitudes on marriage and childbirth among young people have begun to change. In the 2021 Annual Population and Social Security Surveys (The National Fertility Survey), the average number of children unmarried women want was 1.79, dropping below 2 for the first time. About 30% of men and about 20% of women in their early 30s reported that they have no plans to ever get married. Without quick action, this trend will become established and it may become impossible to return to how things were before the pandemic.

On the other hand, the direct causes for medium- to long-term trends are late marriage, late childbearing, and non-marriage. Behind these causes are several factors, including (1) an increase in opportunity costs for women, whose higher education and employment rates have risen (an increase in lost income for women from suspending careers due to marriage and childbirth), (2) a direct increase in the costs of childcare, including education and housing costs, (3) instability and low wages in employment for young people, and (4) a lack of flexibility in working styles at Japanese corporations. A countermeasure against any of these is no easy task.

While it is valiant to talk about “doubling the budget for children” in the Kishida administration’s countermeasures against the declining birthrate, we have yet to see any concrete countermeasures. They had only really decided to raise the Childbirth Lump-Sum Allowance, leaving discussions on the expansion of child allowances and the content of subsidies for workers working shorter hours to the future. The actions of local governments are much faster, with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government deciding on monthly ¥5,000 subsidies, for example.

According to empirical research, the effects of various cash payments and in-kind assistance are not always clear, and if there are any results, they are minimal. In reality, we see no change in the declining birthrate trend, despite making early childhood education and healthcare free in recent years.

This is obvious even from a theoretical point of view. From an economic perspective, childbirth is a type of investment by a couple. The investment amount in children, a type of durable consumer goods, is decided upon by weighing the long-term costs and benefits. The costs of education and living expenses for one child is considered to be between 13 to 30 million yen.

The opportunity costs for women related to raising a child are greater than these direct costs. According to recent research by Professor Yanfei Zhou of Japan Women’s University, the lost income over a lifetime for women with a university degree who suspend their careers to raise a child is around 200 million yen. Even for women with only a high school diploma, the lost income is around 100 million yen. Compared to these tremendous costs, even doubling the monthly ¥10,000 of child allowance would be like a drop in the ocean. It is also not possible to make decisions on investments with an unstable system that constantly changes with each new administration.

When considered in this way, the focus of countermeasures against the declining birthrate should not be on increasing subsidies but in preventing lost income for women. Even now, roughly two-thirds of women who have a child under the age of 18 put their career on hold until after giving birth to their first child. The reason for this is the unchanging Japanese employment practices and institutions that give preference to stay-at-home mothers to support these employment practices.

In reality, characteristics of Japanese corporations, including long working hours, frequent job transfers, and a slow promotion system delaying childbirth, are quite simply detriments to marriage and childbirth for the younger generations, where it is common for both partners to work. The government needs to shift the focus of its policies from the traditional model household of long-term employed husband and stay-at-home wife to one aimed at the Western “dual-career couple,” where both partners continue working while raising children. If the government is talking about unprecedented measures, then it should force revisions to systems giving preference to stay-at-home mothers and to Japanese employment practices.

As an immediate countermeasure against the declining birthrate, the government should make haste to encourage those who were hesitant about marriage and childbirth during the pandemic.

According to 2021 Annual Population and Social Security Surveys, female cohabitation rates have almost doubled since before the pandemic. How about a government-sponsored Post-Pandemic Marriage promotion, in which the government offers partial subsidies for wedding costs and rent for a limited time for young couples who need a little encouragement to decide to get married? It is important to develop a social mood, just as the marriage rate increased with marriages during the first year of the new Reiwa period. Recently, it has become popular to use dating apps to search for a future spouse, but there have been many issues, including use of the apps by people who are already married. The government might actively intervene to improve the quality of the matchmaking market by imposing penalties for false information.

It might also be effective to implement temporary subsidies (subsidies for the 30% portion covered by the patient) for infertility treatments for people who reached the upper age limits for childbirth while abstaining from childbirth during the pandemic.

If the government really wishes to expand the child allowance for political reasons, then they must narrow down the target so that results, however small, can be projected, rather than widely distributing allowances based on budget size. Past empirical research has shown that increasing payments for the birth of second and third children and for low-income households has some effect.

In any case, it is essential to secure financial resources to strengthen countermeasures against the declining birthrate. It has been reported that the government is considering establishing a solidarity fund for childcare support. It would be a system to contribute resources to countermeasures against the declining birthrate from social insurance, including the national pension, healthcare, and nursing. As this system would be similar to existing contributions to children and childcare, it is considered easy to implement politically. However, there are two major issues.

The first issue is that there is a strong possibility that the current working generation that is also raising children will bear most of the costs. The Japanese social health insurance system mainly has the current working generation bear the costs of seniors citizens (a pay-as-you-go system), and the burden on senior citizens is small. The same will surely be true of a solidarity fund. Results cannot be expected as the increased payments will be paid for by households that are raising children. An increase in children and greater sustainability in the social health insurance system will benefit senior citizens, as well. Seniors should also be asked to contribute to this fund equally.

The second issue is that as contributions will be an appropriation of social health insurance premiums, it will be easy for the appropriations to be kept in a black box, making it hard to check where the funds are going. The possibility of these funds being used as subsidies for industrial groups not related to countermeasures against the declining birthrate cannot be denied.

Rather than depending on temporary measures, we should have discussions on securing financial resources fairly and openly. The previously considered “child insurance” system is one such potential option. This system would impose uniform insurance premiums on all residents, including senior citizens, and as the use for these funds to support children is clear, it is easy for the public to check. If the child insurance system is given the same budget as the Children and Families Agency, which is to be inaugurated in April, then it can demonstrate great power as a leader in policies for children.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 27 March 2023 under the title, “Shoshika taisakuno shiten (I): Josei no ishitsu-shotoku boshi ga honsuji (Perspectives on Countermeasures Against the Declining Birthrate (I): The Real Issue is Preventing Lost Income for Women).” The Nikkei, 27 March 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Suzuki Wataru

- Gakushuin University

- declining birthrate

- countermeasures

- fertility rate

- trend

- COVID

- lost income

- Japanese employment practices

- child insurance

- declining marriage rate

- childcare costs

- childhood education

- child allowance

- Childbirth Lump-Sum Allowance

- subsidies

- long-term employed husband

- stay-at-home mothers

- dual career couple

- solidarity fund for childcare support

- child insurance system