Japan and “China” in the Context of the 19th-Century Seikanron Debate on the “Opening” of Korea

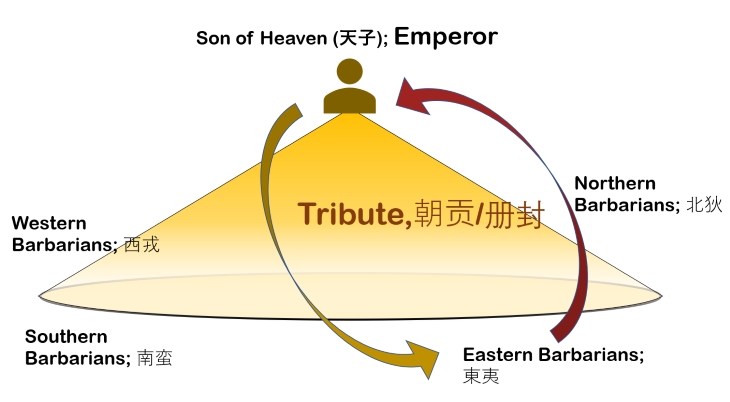

Conceptual diagram of Sinocentrism and Hua-Yi Order

Created by the author

Ishida Toru, Professor, Department of International Relations, The University of Shimane

Introduction: The Contemporary Position of “Zhonghua” in Japan and South Korea

The notion of the “Rising China” started to gain prominence in the mid-1990s. It became more tangible around the time of the Beijing Olympics, and China’s nominal GDP surpassed that of Japan in 2010. Towards the end of November 2012, General Secretary Xi Jinping visited the National Museum of China and delivered a post-study lecture during the “Road of Rejuvenation” exhibition. Reflecting on China’s history since its defeat in the Opium War 170 years earlier, Xi Jinping stated, “[…] what is the Chinese dream? We believe that realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is the greatest Chinese dream of the Chinese nation in modern times,” and introduced the slogan “Chinese Dream.” The “Chinese Dream” encompassed both the “Dream of a Strong Country” and the “Dream of Enriching the People.”[1] Following this, China embarked on the path to fulfill the “Chinese Dream.” For example, it has increased its influence on the Senkaku Islands and Spratly Islands, or promoted the “Belt and Road” initiative (BRI) that spans Eurasia and Africa, promoting economic expansion to various parts of the world.

Against this China, South Korea celebrated the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Korea and China in 2022, but now the atmosphere of “anti-China” is stronger than “anti-Japan,” especially among the younger generation. Yoon Young-kwan, professor emeritus of Seoul National University (former Foreign Minister of South Korea), cited three factors as factors for worsening sentiment toward China: “system, United States, and China.” Regarding China or “Zhonghua” (中华 in Chinese, meaning China and the center of the world)[2], Professor Emeritus Yoon expressed his recognition that “China has a desire to revive China-centered ‘Sinocentrism’ in the Asian continent.” On the other hand, he said, “Korea has become accustomed to a horizontal order that respects the Western international law order and liberalism and emphasizes sovereign equality between countries. Because it is Korea that has grown up in such an order, it does not fit with Sinocentrism.” In other words, he points out the problem of “China-centered Sinocentrism.”[3] Since the Korean Peninsula has historically built a deep vertical relationship with “Zhonghua,” the impact of this indication is not small.

On the other hand, in Japan, the discussion of the “rise of China” is more focused on military power that is more visible in the media than on “Zhonghua (Chinese-ness, or China-centered Sinocentrism).” However, as Professor Emeritus Yoon expresses concern, there is a significant historical context behind the term “Zhonghua” that cannot be easily dismissed. While China may use the familiar word “Zhonghua” quite naturally, the reason one cannot help but be cautious with this term lies in the historical connotations it carries.

“Zhonghua” has a deep connection with Japan, and the word is still commonly used today. Shiba Ryotaro (author, 1923–96)[4] once warned that the term “chilled Chinese [Zhonghua] noodles” should not be taken lightly. Whether they know the meaning of “Zhonghua” and dare to look down on it, or whether they are innocent and don’t know it at all, in either case, modern Japan may take “Zhonghua” lightly. It is not easy for modern Japanese people to understand the weight of “Zhonghua.”

Therefore, this paper focuses on how Japan began to confront “Zhonghua,” mainly in the middle of the 19th century, which leads to the present day. I would like to go back to that point and think about what “Zhonghua” means to Japan.

Confrontation with “Zhonghua” 1: From the perspective of self-awareness

In the first place, the word “Zhonghua” is the self-proclaimed, self-identification of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) built by the Han Chinese in ancient China. Together with this term, the word “Barbarians (夷狄 in Chinese, meaning Barbarians or Four Barbarians; Eastern Barbarians, Western Barbarians, Southern Barbarians and Northern Barbarians)” surrounding Zhonghua was born. This is the recognition of others [夷 Yi; cultural or ethnic outsiders], which considers neighboring countries to be different from themselves [Hua or China] or to be inferior to themselves (barbaric). Both are collectively called “Hua-Yi (thought) (华夷(思想)).” From a different angle, it can also be seen as self-ethnic (or self-group)-centricism.

Furthermore, when we think about the meaning of Zhonghua, one is geographical, so to speak, “center (of the world),” and the other is cultural, so to speak, “the pinnacle of Confucian culture.” Koike Yoshiaki (professor emeritus, University of Toyo) describes the former as a “fixed Hua-Yi thought” that absolutizes and fixes the Hua–Yi distinction based on geographical motives, and the latter is based solely on cultural criteria, abstracting geographical motives. “Fluid Hua-Yi thought” that separates Hua-Yi—Hua-Yi thought as a method[5]. The latter way of thinking is particularly effective in understanding Japan’s self-awareness and external thought.

Hua-Yi thought’s logic as the essence of Confucian Culture is at the center (=Zhou Dynasty /Han Chinese). The farther away from the center, the less Confucian Culture (or Virtue of Heavenly Son at its core). In other words, it is inferior to that extent (the extreme end is “outside of virtue”). Therefore, the “barbarians” paid tribute to “Zhonghua,” and “Zhonghua” subdued the “barbarians.” This relationship—(moral) control using Confucianism—was repeated. Historically, “Zhonghua” has been monopolized (as Zhonghua) by Chinese dynasties, so the “barbarians” surrounding it have had no choice but to form themselves while constantly confronting the above two types of “Zhonghua.”

In other words, in the case of the “fixed Hua-Yi thought,” “China” remains “Zhonghua” and the surrounding countries remain “barbarians.” As long as “China” is the center, Korea and Japan are forced to self-perceive as “Eastern countries, barbarians,” and the only way to escape from that is to become the center. On the other hand, this is not the case with the “fluid Hua-Yi thought.” There is a difference in how “barbarians” can become “Zhonghua” depending on the criteria of “Zhonghua.”

“Transition from Ming to Qing,” where the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty (Zhonghua) was destroyed by Manchus Later Jin and Qing dynasties (both barbarians) in the early 17th century, is also called “Kai Hentai” (Metamorphosis from civility to barbarity) where “barbarians” became “Zhonghua.” This was the result of the physical occupation of the seat of “Zhonghua” = Chinese realm by “barbarians.” In the above two divisions, will it be the flow of “fixed Hua-Yi thought”? However, neighboring countries could not accept this (transition from Ming to Qing) as it was.

In the case of Korea, from the end of Goryeo [918–1392], efforts were made to embrace Confucianism (Cheng-zhu School), and during the Ming dynasty period (1368–1644), it promoted a more accurate understanding and practice of Confucianism. Korea often positioned itself as a close follower of the Ming dynasty. From such self-awareness, even though military threats forced Korea to do “Three kneelings and nine kowtows (三跪九叩之礼)” to the Qing Dynasty and it had no choice but to pay tribute, Korea was aware that no one but Korea could understand the essence of Zhonghua after the fall of the Ming Dynasty and be the successor of Confucian culture. A Little Chinese consciousness emerged that the Manchu Qing Dynasty could not be the successor. Not only that, in Korea, which is commonly understood as “Respect civil, despise and military realms,” in the latter half of the 17th century, it was said that the Qing Dynasty was subjugated in return for the Ming Dynasty and revenge for the destruction of Ming. Even Northern Expedition (북벌론) appeared.

The process of Korea becoming “Little China” is premised on the vacancy of the original “Zhonghua,” and the standard of “Zhonghua” has not changed from traditional Confucianism. In the case of Korea, what was being confronted was, so to speak, “barbaric Zhonghua (Qing Dynasty)” and not “Zhonghua” itself.

On the other hand, in the case of Japan, according to Katsurajima Nobuhiro (professor, Ritsumeikan University), until the first half of the 17th century, it was “Li Wen Chinese Centrism[6]” based on Confucianism. After the transition from Ming to Qing in the latter half of the 17th century to the first half of the 18th century, the conventional standard (Zhonghua) remained, but it emphasized the superiority of “Japan” and put Japan at the center of “Japanese Hua-Yi thought” has appeared. In the latter half of the 18th century, it became “Japanese [Chinese] Centrism” (a discourse that criticizes the theory of “China = barbarians” and claims “Japan = Zhonghua”), appeared notably in “Suika Shinto Thought (a thought of combination of Neo-Confucianism and Shinto).” However, these changes still had the influence of Confucianism, and in the 19th century, the growth of Kokugaku (Native Japan Studies) Thought led to a break from “China = Zhonghua.”[7]

Unlike Korea, Japan confronted “Zhonghua” and proceeded to overcome it. Japan did not pay tribute to the Qing Dynasty, so there was no hesitation to “Zhonghua.” However, as long as Confucianism was the axis = standard of the concept of “Zhonghua” itself, Japan could never occupy the position of “Zhonghua.” And in order to become “Zhonghua (Center),” Japan moved away from Confucianism and brought up “military glory” and “Emperor of Bansei-Ikkei (Unbroken Imperial line)” as different criteria. After the defeat of Qing in the Opium War, Sato Nobuhiro (1769–1850) said “Manchuria and the Qing Dynasty also became barbarians, and England also became barbarians,” and “I want Qing to be the western (defensive) wall of our country forever[8]” clearly showing the departure from “China = Zhonghua.”

Confrontation with “Zhonghua” 2: From the perspective of order

The “Zhonghua” that Japan confronted was not only about self-awareness. In building relations between countries, Japan once again ran into the wall of “Zhonghua.” This wall was not only Qing, but the tribute structure that Qing built. One specific arena of conflict was diplomacy with Korea during the transitional period of modernity (the other is Ryukyu). There were two major aspects. One is the clash between the Western-style state relations/diplomatic order and the Chinese [Zhonghua] order (= establishing relationships between suzerain and vassal countries through tribute), and the other is the clash in diplomatic negotiations with Korea.

The former conflict is the question of whether the countries paying tribute to Qing are independent when viewed from the Western order of “Sovereign nations are equal”[9]. If a country were to establish an equal relationship with Korea, what would happen to the relationship between that country and Qing? Even within the Japanese Foreign Ministry after the Meiji Restoration, several options were prepared for how to treat Korea, such as viewing it as an “independent country” or viewing it as a “semi-independent/semi-vassal state.” The Meiji Restoration Government proceeded in various ways in a Western manner—since it was a policy to set the standard of behavior in the Western style, it ultimately approached with a policy of being regarded as an “independent country.” Article 1 of the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876, which concluded with Korea after the Ganghwa Island incident (1875)[10], begins with Korea was “an independent state enjoying the same sovereign rights as does Japan.” It is a manifestation of the fact that the focus was on whether it was independent or not.

However, despite this conclusion, Korea and Qing continued to maintain a tribute relationship, so Japan deepened its conflict with Korea and Qing. The Sino-Japanese dispute over Korea ultimately ended in military clashes. The beginning of Article 1, Treaty of Shimonoseki (concluded the 1894–95 Sino-Japanese War) was to confirm that “China [Qing] recognizes definitively the full and complete independence of Korea.” However, the extent to which Japan respected the independence of its “full and complete independence” is another matter.

The latter conflict is commonly known by the term “Shokei Mondai (problem of letters).” Briefly, it was a matter of negotiations between after Taisei Hokan (Restoration of Imperial Rule of Japan), the Tsushima domain (currently Tsushima City in Nagasaki Prefecture) and the Korean government (the corresponding department is Dongnaebu [동래부, a contact point for early-modern Japanese-Korean diplomacy in present-day Busan City]). Words such as “royal/imperial (皇)” and “imperial decree (勅)” and content that denies the traditional Tsushima-Korea relationship were written in the letter (shokei) from the pre-negotiation messenger in which Tsushima notified Korea of the “Restoration.” Therefore, the Korean side refused to receive it.

Why did the Korean side refuse to receive it? First, the words “royal/imperial” and “imperial decree” were only available to Qing Dynasty, “Zhonghua.” As we saw earlier, there was certainly a Little Chinese consciousness in Korea. But from the latter half of the 18th century onwards, instead of viewing Qing as barbarians and loathing it, a philosophical trend of “Northern Learning” (learning from the Qing Dynasty) emerged, coexisting with the “Northern Expedition”[11]. In addition, during the 200 years of Korean tribute, flunkyism to the Qing Dynasty was deeply rooted in Korea, so Korea could not accept the words “royal/imperial” and “imperial decree” from countries other than Qing. From Korea’s point of view, Japan could never stand side by side with Zhonghua, and Japan’s use of the word “imperial” was enough to suspect that it was a manifestation of its ambition to invade Korea again. In other words, Japan did the restoration without paying tribute to Qing, and it was a strange country in East Asia at that time that did not pay attention to “Zhonghua” and used “royal/imperial” and “imperial decree” without hesitation. Japan unintentionally and naturally collided with “Zhonghua.”

Furthermore, the fact that the letter was brought by none other than Tsushima Domain (So clan) was a major reason for refusal to receive it. Since the Middle Ages, Korea and So clan have had a hierarchical relationship that could be called a pseudo-tribute relationship. Naturally, the “higher rank” is Korea. The “lower” So clan has used the “Restoration” as a rare opportunity to deny the traditional relationship. Of course, Korea could not accept it at all.

In this way, the stalemate in Japan-Korea diplomacy in the early Meiji period consisted of two conflicts, <Tsushima Domain tried to change the conventional relationship and Korea did not allow it> and <The Meiji Restoration government, which switched to a new Western-style standard, and Korea, which firmly adhered to the precedent = Confucianism.> It should be noted that the origin of the problem (Shokei Mondai) was not the Korean side’s “Expulsion of foreigners” policy toward Japan.

Another conflicting issue that emerged from the diplomatic negotiations at that time was the “protocol” issue. In contrast to Korea, which insisted on sticking to the “Zhonghua” axis and adhering to the Confucian protocol as before, Japan insisted on adopting a new Western-style protocol. One of the toughest points of contention was dress code. Japan, which set the standard of behavior to the West, adopted Western clothes for official government clothes, but Korea, which saw the West as “barbarians” based on Confucian standards, did not accept it. Korea has rather strengthened its “integrated view of Japan and the West,” which sees Japan and the West as one. Of course, there were also voices in Korea that Japan’s changes should be accepted as Japan’s problem, and that if Japan was irritated by rejecting it unnecessarily, it would lead to Japanese aggression. However, it never became mainstream within the Korean government at the time.

Pre-stage of Seikanron

In this way, Japan during the Meiji Restoration had problems with Korea from the very beginning. Inevitably, a stern opinion of Korea—Seikanron (theory of conquering Korea)—appeared. But Seikanron didn’t suddenly appear. For the time being, from the perspective of the flow of Japan’s external thought at the end of the Edo period, it can be roughly summarized as follows.

The “Western impact,” such as the defeat of the Qing in the Opium War (1840–42) and the reluctant treaties Japan was forced to sign (1854/1858) left the Japanese ruling class with a profound sense of crisis and humiliation. Overseas expansion was sought to overcome this problem. After the arrival of the Black Ships, a fierce conflict arose within Japan over whether to open the country or expel the foreigners. Surprisingly, however, those who opposed the opening of the country did not feel any resistance to going on business trips outside of Japan to conduct trade (outbound trade). Tokugawa Nariaki (1800–60), a staunch proponent of expulsion of foreigners, and Ii Naosuke (1815–60), who decided to open the country, argued that trade should be conducted outside of Japan, Nariaki went so far as to say that he would personally go to America with “three or four million people, including the second and third sons of ronin, peasants and townspeople.[12]” They were preempted by the West and forced to react passively without any initiative of their own. They felt a sense of crisis and deep humiliation about this, and in order to overcome it and avenge themselves, they thought that the only option was to take the initiative and invade overseas—to expand.

Such discussions are characterized by an omnidirectional expansion into surrounding countries and regions. Hashimoto Sanai (1834–59)[13], famous for the so-called “Seikanron (theory of conquering Korea) at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate,” argued that “Shandan (Lower Heilong River area), surrounding Manchuria, and Korea must be annexed and possessions must be obtained in the United States or India (however, since it is not possible now, we should ally with Russia).[14]”

A more famous argument by Yoshida Shoin (1830–59)[15] is that “Our country (those who are committed to maintaining the country well) should urgently prepare its military and open up Ezo (Hokkaido), granting it to various daimyo (feudal lords). Seizing the opportunity, we should take Kamchatka Peninsula and Okhotsk. Then, persuade Ryukyu to become one of our country’s vassals, question Korea and make them pay tribute as in ancient times. We should govern from Manchuria in the north to Taiwan and Luzon in the south, demonstrating a progressive and enterprising spirit[16]”), or after the conclusion of the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (Convention of Kanagawa) Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia (Treaty of Shimoda), “It would be better for Japan to build up its national power, pacify Korea, Manchuria, and China, which are easy to take, by force, and recover the amount lost in trade with Russia in Korea and Manchuria.[17]”

On the other hand, Yamada Hokoku (1805–77), who served as a brain to Senior Councilor of the Shogunate, Itakura Katsukiyo (1823–89), argued that in order to protect the Shogunate, which had lost its influence compared to influential domains in the southwestern region (such as Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa, and Hizen), he proposed to the major domains like Mito, Echizen, Hizen, Higo, and Choshu, “First, begin with a campaign against Korea, then shift to Northeast China, sweep through Manchuria and the Shandan (Lower Heilong River area), and finally extend their influence to Northern Ezo (Sakhalin) to block the path of the ‘Russians’.[18]”

Theory of conquering “Korea”

As can be seen at a glance, in these discussions, Korea is just one of many neighboring countries and regions. There were two catalysts for the fixation of Korea as the subject of such discussion. One is the Kokugaku factor centered on Japan, as shown in Shoin’s earlier discussion of “make them [Korea] pay tribute as in ancient times.” Above all, it is the understanding of Korea based on Nihon Shoki (The Chronicles of Japan) that later becomes Kokokushikan (emperor-centered view of history). Nihon Shoki details that Ancient Korea (Three Hans [Shilla, Baekje and Goguryo]) paid tribute to Japan. The important point here is not whether it is historical fact or not, but that those who read Nihon Shoki, including Shoin, took it as historical fact. Shoin was furious that Korea, which had not paid tribute for a long time, had to make tribute again.

These discussions are not limited to Shoin. For example, his disciple Kido Takayoshi (1833–77) wrote in his diary on December 14, 1868 (solar calendar January 28, 1869), “Send envoys to Korea, inquire about their impudence, and if they do not submit, strongly condemn their wrongdoing, attack their land, and fervently hope to enhance the prestige of the divine nation of Japan” (Diary of Kido Takayoshi 1),” trying to blame Korean “impudence.” However, this “impudence” does not refer to “Shokei Mondai (problem of letters),” but also to ancient Korean tribute. Similarly, Gaimu-Daijo (Senior Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) Sada Hakubo (1833–1907), who advocated the so-called “The Thirty Battalions’ Theory of Conquering of Korea” in 1870, said, “Since the time of Emperor Ojin [the 15th Emperor], Japan has a duty (responsibility to take care of) Korea, so it would be good to take advantage of the momentum of the Meiji Restoration and quickly take measures.[19]”

Speaking of the theory of conquering Korea, “Saigo Takamori’s theory of conquering Korea” in 1873, which has become the most famous, is “Saigo himself travels to South Korea to try to resolve the stalled diplomatic negotiations between Japan and Korea, and persuades the Korean government, but the Korean government is likely to ‘murder’ Saigo, so attack (Korea) afterward.” It is not clear what Saigo was trying to persuade when he went to Korea. However, from the standpoint of seeing Saigo’s claim as the “theory of conquering Korea,” it is emphasized that he was trying to correct the “meibun jori (a just cause and reason)” of the Restoration of Imperial Rule and the Meiji Restoration[20].

The key point of the theory of conquering Korea is that it tries to reproduce “Tribute to Japan (Emperor) by Three Hans” written in Nihon Shoki, that is, Japan is the center and the target is fixed to Korea.

Another catalyst was the Tsushima Domain (Izuhara Domain). In the case of Tsushima Domain, the premise of the discussion is Korean diplomacy, so naturally the subject of discussion is fixed to Korea. The Tsushima Domain was involved in interactions with Korea throughout the Edo period (1603–1867). However, at the end of the Edo period, due to factors such as the slump in Korean trade, the domain proposed seven measures to the shogunate to reform the existing Tsushima-Korea relations. The Tsushima clan persuaded the Korean side to present these reform proposals and urged the Shogunate to make the “courageous choice to implement significant punitive measures” if the Korean side did not acquiesce[21].

In addition, even after Taisei Hokan (restoration of imperial rule), the Tsushima Domain still offered its opinions to the Meiji Restoration government on how Korean diplomacy should be. Even at that time, the Tsushima said that Korea should “be attached to its inherent bad habits, fail to understand the meaning of imperial Japan’s loyalty, and if by any chance there is a feeling of disrespectful arrogance, make the “courageous choice to implement significant punitive measures.” Tsushima Domain repeated the theory of conquering Korea since the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, stating that the reign of an emperor who excels in valor should be established, and incited the Meiji Restoration government[22].

Tsushima Domain developed the theory of conquering Korea in the form of negotiating with Korea and urging the Japanese central government to make the “courageous choice to implement significant punitive measures” when the Korean side disagrees. In the theory of conquering Korea of this Tsushima Domain, there is a pattern pointed out by Kimura Naoya (Specially appointed professor, Rikkyo University), which is common to the theory of conquering Korea that will appear later, “First persuasion → If not accepted, then revenge.[23]” The theory of conquering Korea by Kido and Saigo mentioned above is also “negotiate first, then attack when negotiations are unsuccessful.” In this sense as well, the impact of Tsushima Domain on the theory of conquering Korea is not small. Moreover, Tsushima Domain said within the domain that if the Meiji Restoration Government actually invoked force, it would be “The calamity of Korea is the calamity of Tsushima right in front.[24]”. It was a very dangerous game of fire.

Also worth noting is the word “yocho (punishment).” “Yocho” is “chastisement,” even if it’s just rhetorical. This is because the side doing “yocho” is standing “upper” and looking down. Is it unreasonable to try to read the nature of “Zhonghua” here? In fact, however, the term was often used against China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, for example (“punish savage China”), or by China against Vietnam during the Sino-Vietnamese War. The situation in which “yocho” is used is very disquieting and should be taken with caution.

As described above, in Japan’s external thought, Korea changed from being treated as “one of them” to being treated as “only one” through two catalysts from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji Restoration. In this trend, “Shokei Mondai (problem of letters),” “diplomatic protocol,” and the Ganghwa Island incident (1875) occurred, and the theory of conquering Korea was advocated.

Sada Hakubo’s the theory of conquering Korea mentioned above was discussed in 1870 after the occurrence of “Shokei Mondai,” and the theory of conquering Korea also appeared that it extended to the use of force—gunboat diplomacy to protest against the refusal to receive letters. For example, Foreign Minister Soejima Taneomi (1828–1905) later wrote, “At that time, I was actually the person who was responsible for the theory of conquering Korea. As well as my theory of conquering Korea, it conformed to the correct reasoning that is widely accepted in international law, and it was a claim that justly accused the crime of the Korean imperial court.”[25] The “crime of the Korean imperial court” here is thought to refer to Shokei Mondai, and Soejima brought up “correct reasoning that is widely accepted in international public law” to protest.

Seen in this way, the theory of conquering Korea was not only a mere theory of aggression against Korea, but also a challenge to “Zhonghua,” which was the background. First, the theory of conquering Korea, which appeared from the end of the Edo period, was influenced by Kokugaku, and the idea of placing Japan at the center appeared. And in the theory of conquering Korea during the Meiji Restoration, the idea of switching the standard from “Zhonghua” (Confucianism) to “Western civilization” appeared.

Closing Thoughts: The Prospects for the “Zhonghua” paradigm

The concept of “Zhonghua” was not only a problem for its original China, but also had a profound effect on the self-perceptions of neighboring countries. This is because if nothing is done, neighboring countries will continue to be “barbarians.” If it is not tolerated, there will be a movement to become a “Zhonghua.” Zhonghua’s excessive self-esteem will stimulate their inferiority complex and evoke more radical reactions. For Japan, “Zhonghua” was not just the existence of China as a nation. At first, Japan accepted the civilization standard of “Zhonghua,” but later rebelled against it and changed to a standard (civilization) that departed from that framework. The change in self-awareness in early-modern Japan is proof of this.

In the 19th century, despite being able to break away from “China as Zhonghua” due to kokugaku (national study) factors, Japan was assigned a different standard—Western civilization (so to speak, the “West as Zhonghua”!?)—due to Western impact. What’s interesting about Japan is that, like its acceptance of Confucianism, it accepts the standards of Western civilization with relative ease. Under this new standard, the previous norm of “China as Zhonghua” was perceived as “barbaric and uncivilized,” and Japan positioned itself as being in a state of “semi-civilization.” From there, Japan pursued a policy of “civilization and enlightenment” to advance towards “civilization,” eventually developing to the point where it stood alongside the Western powers as a permanent member of the League of Nations. This can be explained by the logic of a fluid consciousness of “Hua-Yi” distinctions.

By the way, looking at it this way, there are actually some points of interest in Japan’s subsequent trends. Because, just like when Kokugaku first appeared, as long as the standard is in the West, Japan can’t be the center. As was the case with China in the past, the West’s pride was strong, and its disdain for non-Western countries was deep-rooted. This is because Japan’s self-awareness in front of the West—the feeling of inferiority—is unbearable, and the idea of breaking free from the yoke of Zhonghua = the West and making itself the center of reference once again revives.

Its symbolic appearance can be seen in Kokutai meicho undo (movement for clarification of the fundamental concepts of national policy [questioning of the Emperor Organ Theory])[26] and “Kokutai no Hongi” (Cardinal Principles of National Polity), which appeared in 1935. “Kokutai no Hongi” utterly denied Western standards, including constitutionalism, liberalism, and democracy that originated in the West, and which had been desperately adopted since the Meiji Restoration. And it was converged with the praise of “Emperor of Bansei-Ikkei (Unbroken Imperial line).” It was after this that the aforementioned Sato Nobuhiro and others were touted as pioneers of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” and the slogan “punish savage China” flew around.

After all, it is now “chilled Chinese [Zhonghua] noodles.” “Zhonghua” is a kind of trauma for Japan. In order to suppress this, the Japanese may be trying to turn away from the yoke of the “Zhonghua” standard by limiting “Zhonghua” to the existence of China as a nation and making light of it.

Korea, on the other hand, did not and could not replace standards in this way. This is because the Little Chinese consciousness was established according to the conventional Zhonghua criteria = Confucianism, and Koreans had a strong belief in Confucianism. As pointed out by Professor Emeritus Yoon at the beginning, of course there is no Little Chinese consciousness based on Confucianism in South Korea today. However, just as Japan repeatedly withdrew from “Zhonghua,” it would be worth paying attention to see if something like a Little Chinese consciousness is emerging in South Korea. I hope that both Japan and South Korea will not fall into the trap of “Zhonghua.”

Translated from “Seikanron kara miru Nihon to ‘Chuka’ (Japan and ‘China’ from the perspective of the 19th-Century Seikanron Debate on ‘Opening’ Korea),” Asteion, Vol. 098 2023, pp. 38-49. (Courtesy of CCC Media House Co., Ltd.) [August 2023]

Keywords

- Ishida Toru

- University of Shimane

- Zhonghua

- Zhou Dynasty

- Qing Dynasty

- Confucianism

- sinocentrism

- barbarians

- Korea

- Little China

- Japan

- Rising China

- Chinese dream

- Hua-Yi thought

- diplomacy

- Shokei Mondai (problem of letters)

- expulsion of foreigners

- Tokugawa Nariaki

- Ii Naosuke

- self awareness

- dress code

- Kokugaku (native Japan studies)

- Emperor Organ Theory

- Seikanron (theory of conquering Korea)

- Tribute to Japan (Emperor) by Three Hans

- Nihon Shoki

- Tsushima Domain

- Meiji Restoration

- Yoshida Shoin

- pay tribute

- Saigo Takamori

- Kido Takayoshi

- Sada Hakubo

- Sato Nobuhiro