“Value-Oriented Diplomacy” and Its Issues in Modern Japanese History

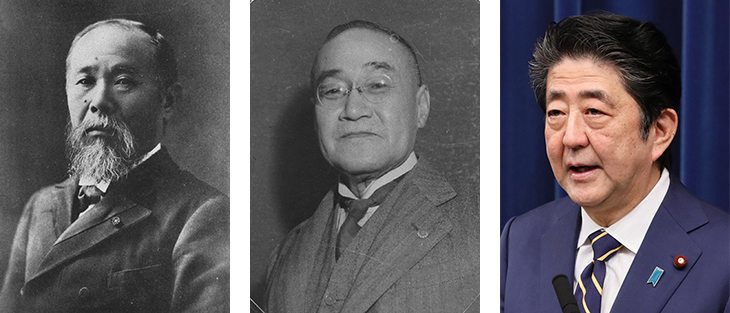

Ito Hirobumi (1841–1909), Yoshida Shigeru (1878–1967), and Abe Shinzo (1954–2022) were politicians who represented their times, and their diplomacy could be called “Value-Oriented Diplomacy.”

Photos of Ito and Yoshida: Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/)

Abe: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Naraoka Sochi, Professor, Kyoto University

When we look back on the history of Japanese diplomacy since the Meiji period (1868–1912), what kind of consistency is there to find? I shall attempt to consider some of the challenges of today in light of the history of value-oriented diplomacy.

Since the first Abe administration (2006–2007), it has been said that Japan pursues a “value-oriented diplomacy” based on universal values, which includes basic policies like the “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity” and a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.” Conversely, more conventional Japanese diplomacy has seldom been seen as having put values at the forefront. But what was the actual situation? I don’t think Japanese diplomacy was as thoroughly realist as people usually imagine. Rather, I think it has been quite consistent in the sense that it has actively accepted and emphasized the values that underpin Western countries today. In this paper, I would like to look back macroscopically on the “value-oriented diplomacy” of modern Japan from this perspective as well as examine its future direction and challenges.

“Value-oriented diplomacy” in the Meiji period

The opening of Japan in the Bakumatsu years (end of the Edo period; between 1853 and 1867) signified Japan’s reception of the concept of sovereign nation equals, the distinction between civilized and non-civilized countries, international law, and the resident diplomat system, all of which were basic ideas and institutions that supported the diplomacy of the Western powers. China (the Qing Dynasty) and Korea gradually came to embrace similar principles, but compared to the two, steeped in traditional Sinocentrism, the reception in Japan was prompt and thorough.

For example, Japan was the first of these three countries to send a permanent diplomatic envoy to Western countries. Even in Japan, the Joi Movement (the movement advocating the expulsion of foreigners), the murders of foreign nationals, and other incidents occurred during the Bakumatsu years and the beginning of the Meiji period, showing that the reception of Western diplomatic methods was not trouble-free, but it is worth noting that Japan was one of the first non-Western countries to adapt, its reception never wavering. This was not simply a successful transplant or import of institutions, but rather the result of Japan accepting the basic values of the Western countries that support these institutions.

What Japan learned from the Western countries was not limited to the diplomatic methods. The Meiji government engaged in the construction of a modern nation under the slogans of civilization and enlightenment and strengthening of military power, yet it not only sought to build a strong and prosperous country, but also importantly aimed to create a constitutional state modeled on Western countries.

There were many twists and turns to these processes, such as the Seinan War (Satsuma Rebellion) fought over whether to pursue the modernization line or not in 1877 and the conflict between the government and the Movement for Civic Rights and Freedom over when and how to introduce a constitutional system [in the 1880s], but when the Meiji Constitution was enacted in 1889 and the Diet was opened, this concluded one chapter of the movement to build a constitutional state. Although there were still many deficiencies, such as restrictions on freedom of speech, by the mid-Meiji period, Western-style liberal democracy had taken root with both values and systems having become fairly well established in Japanese society.

These shared values were actively advertised to the Western powers by the Japanese government. This was evident in the imperial edicts issued in the name of the emperor during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars. Both edicts were carefully drafted by the government, emphasizing that Japan was committed to fighting the wars in compliance with the international law as well as that war had become unavoidable despite Japan’s treasuring of “civilization” and “peace.” During the Russo-Japanese War, Japan dispatched Kaneko Kentaro (1853–1942) and Suematsu Kencho (1855–1920) to Britain and the United States to concretely demonstrate that Japan as a “civilized country” values the same shared values as those countries, such as being in compliance with international law, freedom of religion, and the opening of the door in Manchuria. As a result, Japan gained the empathy of the Anglo-American public, which led to the acquisition of funds for the war effort and other positives. This is the first full-fledged example of Japanese “value-oriented diplomacy” in practice.

Similar imperial edicts and government-issued documents were issued during World War I and the dispatch of troops to Siberia, so it is clear that Japanese diplomacy from the late Meiji period into the Taisho period (1912–1926) attached importance to signaling to the Western powers that they have common liberal values.

The “Ito Doctrine” and beyond

The “value-oriented diplomacy” at the time was inseparably linked to imperialism. The primary concern of Japanese diplomacy was the maintenance and expansion of territory and interests, so diplomacy was not conducted to disseminate or realize liberal values. As such, while Japan’s political leaders were eager to advertise the sharing of values with Western powers, they showed little interest in the sharing of values with Asian countries, meaning that the idea of solidarity with Asia (Pan-Asianism) never became the mainstream in the Japanese government. Seen as neither “civilized countries” nor countries with shared values, China and Korea eventually became the subject of Japanese territorial expansion.

Having said that, Japan’s political leaders were by no means favoring imperial expansion across the board. Ito Hirobumi (1841–1909), the most powerful man of the latter half of the Meiji period, believed that territorial expansion should be curtailed as much as possible. Ito’s fundamental political vision was one of state development while developing parliamentary politics internally and promoting international cooperation and commerce and trade externally. As such, Japanese foreign policy in the latter half of the Meiji period may be regarded as having been formed with Ito largely taking the lead, although there was antagonism and coordination with other leaders in the clannish government and military as well.

I believe that what may be termed the “Ito Doctrine” served as the basic idea that defined Japanese diplomacy in the Meiji period. Ito, who had a wealth of experience in Europe and the United States, was also enthusiastic about “value-oriented diplomacy” and had many opportunities to communicate his ideas in English. The aforementioned outreach to the Anglo-American public during the Russo-Japanese War was also the brainchild of Ito.

This diplomacy thus emphasizing and disseminating international cooperation and liberal values was inherited by Saionji Kinmochi (1849–1940), Hara Takashi (1856–1921), and other political successors of Ito. Especially Hara, who served as prime minister in the post-WWI period when the world order underwent a transformation, navigated foreign affairs admirably. Hara was an active participant in the Paris Peace Conference and the Washington Conference and promoted international cooperative diplomacy. He also curbed the expansion of interests in China and strengthened trade relations between Japan and China.

During the Paris Peace Conference, Japan was unmotivated to participate in the creation of a new international order, so the Western powers often criticized Japan, calling it a “silent partner.” Certainly this was due to language barriers and geographical disadvantages, but the communicative ability of Japanese diplomacy also was less than sufficient. However, it is quite significant that Hara, Saionji, the Japanese delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, Makino Nobuaki (1861–1949), and others accurately grasped the major changes in international politics after WWI and executed a major shift from the conventional policy of expansion to international cooperative diplomacy.

Although it is not a well-known fact, Hara thought that human history had entered a new phase after WWI and said that there is a need for “Harmony between Eastern and Western Civilizations.” Makino also explained at the Paris Peace Conference that Japan’s policies had changed significantly, earning the trust of US President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924). At the conference, Japan also put forward the Racial Equality Proposal, which was not adopted in the end but was of groundbreaking significance in human history.

The diplomacy of the Hara administration was followed by the Shidehara diplomacy [by Shidehara Kijuro, 1872–1951] in the early Showa period. However, as expectations for mainland expansion grew amid the fluidity of the Chinese situation and the recession in Japan, the rise of the military meant that the political camp following the “Ito Doctrine” lost influence. As party politics and international diplomacy declined, Japan gradually became more and more nationalistic and began to advocate its hegemony over Asia, and following the outbreak of the [second] Sino-Japanese War, it began promoting the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Greater East Asian War was a result of that. When that war was declared, no reference was made to compliance with international law. This is indeed suggestive and illustrates that Japan was engaged in self-righteous diplomacy without regard for the universal values shared with Western countries.

“Value-oriented diplomacy” after World War II

After WWII, Japan was reborn as a peaceful and democratic nation. Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru (1878–1967), who laid down the basic diplomatic line of postwar Japan, admired and was strongly influenced by Ito, Saionji and Makino, so it is possible to view the “Yoshida Doctrine” as an extension of the “Ito Doctrine.”

Yoshida gave his famous acceptance speech when he signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951. This speech is often highlighted as providing an explanation of his basic position on the issues of territory and reparations, but it is also important in the sense that Yoshida conveyed to the world what he envisioned that postwar Japan ought to be like. In this speech, he uses the word “peace” 29 times, the word “democracy” a total of 3 times, and the word “freedom [and free]” 6 times to describe how Japan was reborn. When he said, “Japan of today is no longer the Japan of yesterday. We will not fail your expectations of us as a new nation dedicated to peace, democracy, and freedom,” it clearly conveys an image of how he envisioned the nation.

Since then, Japanese prime ministers and foreign ministers have repeatedly signaled that Japan values “peace,” “democracy,” and “freedom,” for example in the United Nations General Assembly and joint communiqués with the advanced Western nations. When Japan joined the United Nations in 1956, Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru (1887–1957) spoke before the UN General Assembly, saying that Japan also places great importance on [UN] maintenance of peace and humanitarianism and that it is ready to become a “bridge between the East and the West.” Prime Minister Ikeda Hayato (1899–1965), the first Japan prime minister to address the US Congress in 1961, said that Japan’s ideal was to create a nation based on democracy and that “the democratic principles of freedom and respect for human rights are now firmly embedded in the minds of Japan’s people.” Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi (1919–2007) commemorated the 50th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1991, remarking that postwar Japan has worked hard for world peace and prosperity so as not to become a “military great power,” with Japan and the United States sharing the same “values” and being connected by deep trust and friendship 50 years onward.

Such speeches and statements have not been given much emphasis in the past, perhaps because they have been regarded as beautiful rhetoric that speaks of ideals or public positions. However, it is a significant fact that Japan has consistently maintained its position as a peaceful and democratic nation for more than 70 years since the end of World War II, continuously communicating such values to the rest of the world. In a sense, you could say that Japan has engaged in “value-oriented diplomacy” for many years, albeit modestly.

Japan has spoken of and practiced the core values it holds dear, even if not so loudly. The words of postwar diplomatic leaders make it clear that Japan belongs to the Western bloc not only because of obedience to the United States or pragmatism, but also because it shares values in addition to national interests with Western countries. In this regard, the basic position of Japan has not changed significantly since the end of the Cold War. The “value-oriented diplomacy” that has become more active since the start of the new century is an extension of such developments.

Three challenges for Japanese diplomacy

Today, “value-oriented diplomacy” has become something exceedingly important for strengthening cooperation with other countries as Japan implements realistic diplomacy that emphasizes its national interests and Northeast Asia faces a challenging security environment, but it also involves a few difficult problems. I would like to discuss three of them.

The first problem is how to reconcile “value” and “profit.” Kosaka Masataka (1934–1996), a specialist of international politics, has pointed out that international politics consists of the three phases of “power,” “interest,” and “value.” From this perspective, while Japan’s “value-oriented diplomacy” has generally been linked to the phases of “power” and “value,” it has seemingly struggled with how to relate to the phases of “interest” and “value.”

After the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989 and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Japan did not necessarily toe the line of economic sanctions by Western industrialized countries, instead seeking to improve relations with China and advance negotiations on the Northern Territories with Russia. These are examples of Japan prioritizing relations with non-democratic powers over the fundamental values it advocates. It is difficult to determine whether “value” or “interest” should have been prioritized in each case, so we need to await future historical evaluations, but this issue in “value-oriented diplomacy” is not limited to Japan. With the current Ukrainian War, all western countries are facing a major challenge about how to build relations with the global south as it does not participate in economic sanctions against Russia.

Secondly, there is the problem of how to position relations with Asia in “value-oriented diplomacy.” This paper shows that pre- and postwar Japanese diplomacy has consistently emphasized the sharing of values with Western powers and advanced nations. On the flip side, this means that values have not been shared or emphasized much with non-Western countries. After the end of the Cold War, as Asian countries grew economically and democratized, values such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law came to be shared among some countries. However, this has often not necessarily led to security cooperation. Moreover, there was a time in the 1990s when attempts were made at creating and sharing of “Asian values,” but there is little on that front today. How to build relations with Asian countries in terms of values is a problem both old and new.

In connection with this, there is concern that issues of historical perspectives will become a bottleneck in the development of Japanese “value-oriented diplomacy.” Since the late 1980s, amid various issues concerning history textbooks, comfort women, and such, the Japanese government has made efforts for reconciliation, including issuing the Murayama Statement and conducting joint historical research with other countries. The Abe administration likewise addressed this issue, presenting the Abe Statement [on the 70th Anniversary of the end of WWII] and concluding the comfort women agreement with South Korea. However, compared to the progress made in postwar reconciliation with Western countries, including Prime Minister Abe Shinzo (1954–2022) and President Barack Obama making mutual visits to Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima, it is difficult to say that reconciliation with Asian countries has progressed sufficiently. This problem is linked to the political systems of Asian countries and the popular sentiments on both sides, and although this is not easy to resolve, a need for steady and sincere efforts will likely remain.

The third problem is how to position liberal values such as peace and human rights in actual diplomacy. One of the issues that Japan cannot avoid when talking about peace is the nuclear issue. Today, when the possibility of nuclear arms use is increasing at an all-time high, Japan as the only country to have suffered atomic bombings has an extremely important role to play.

Can the Hiroshima Summit be used as an opportunity?

This year’s G7 Hiroshima Summit is hosted by Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, who is from Hiroshima and has a strong commitment to nuclear abolition. At the same time, that is not something easy to realize, and the Japanese government’s policy is not to eliminate nuclear weapons, but to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and to prevent the nuclear powers from ever using them again. Prime Minister Kishida has also explained this idea in his book Kakuheiki no Nai Sekai e (Toward a World Without Nuclear Weapons) (Nikkei BP). While this position often appears evasive and half-hearted, it is clear that it is impossible to advance directly to nuclear abolition, although diplomatic leaders have a responsibility to explain both the harsh reality and the ideals they should seek to attain. In this regard, the summit is a good opportunity, and I look forward to hearing Prime Minister Kishida’s message.

Finally, so-called “human security” that includes human rights relief, the environment, refugees, and poverty is also an important theme in “value-oriented diplomacy.” In recent years, the Japanese government has made tackling this problem a priority and is actively working on it through ODA and other means, but these efforts have been criticized for not being sufficient, owing to declining economic power and financial difficulties. As long as Japan advocates “value-oriented diplomacy,” it will be necessary to continue the steady efforts by paying attention not only to national security but also to areas such as this.

Translated from “Tokushu 1 Rekishiteki-tenkanten no Nihon Gaiko: Nihon Kindaishi ni miru “Kachhikan Gaiko” to Kadai (Special Feature 1 Japanese Diplomacy at a Historical Turning Point: “Value-Oriented Diplomacy” and Challenges in Modern Japanese History),” Voice, May 2023, pp. 68-75. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [July 2023]

Keywords

- Naraoka Sochi

- Graduate School of Law

- Kyoto University

- value-oriented diplomacy

- foreign policy

- Ito Hirobumi

- Yoshida Shigeru

- Abe Shinzo

- Meiji period

- universal values

- realist

- Bakumatsu

- Western-style liberal democracy

- peace

- freedom

- democracy

- Ito Doctrine

- Paris Peace Conference

- Racial Equality Proposal

- Yoshida Doctrine

- San Francisco Peace Treaty

- power, interest and value

- human rights

- Hiroshima Summit

- nuclear weapons

- human security