Europe: De-risking as a strategy for economic self-reliance

At the Japan-EU Summit Meeting held in July 2023, in terms of economic security, the leaders discussed coordinating to build resilient supply chains, reducing strategic dependencies, and responding to economic coercion. At this time, the two sides also signed a memorandum of understanding on semiconductor cooperation, which aims to establish an early warning mechanism for the semiconductor supply chain and enhance cooperation in semiconductor research and development.

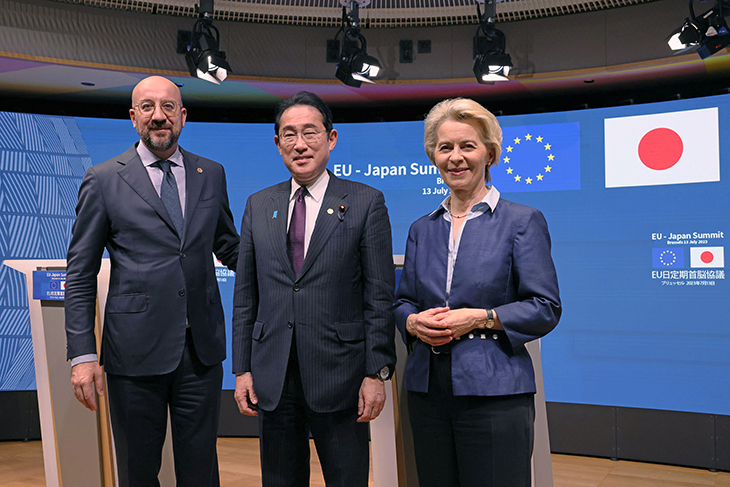

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Unlike the American decoupling approach, de-risking is attracting more attention as an approach to China spearheaded by Europe. This is characterised by tightening regulations in specific fields for economic security. This article explains what measures the EU is taking and what are Brussels’ aims.

Hayashi Daisuke, Associate Professor, Musashino Gakuin University

At the G7 Hiroshima Summit in May 2023, the G7 announced its commitment to a de-risking approach towards China. The concept of de-risking was originally proposed by the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, and was later incorporated into the G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué with other member states, such as the United States and Japan.

However, what is the concept of de-risking, and how does it differ from decoupling? I provide an overview of the origins of the concept of de-risking, specific policy developments, and cooperation with other countries.

Decoupling and de-risking

While some experts argue that there is no substantial difference between decoupling and de-risking because of the ambiguity of these two conceptions, I evaluate de-risking as different from decoupling, particularly in terms of goals and objects. First, the concept of decoupling has the nuances of disconnecting or separating from interconnected relationships, and has been used mainly when it is intended to cut off economic relations or military alliances. In this sense, decoupling may include the termination or separation of relationships as its goal.

On the other hand, the concept of de-risking focuses on risks such as excessive dependence and imbalance rooted in relationships, rather than the relationships themselves, and aims to reduce these risks. As such, it is intended not to break relationships, but to develop healthier and more stable ones by reducing risks while maintaining the connection. In this sense, de-risking is not necessarily argued in a negative context but can be interpreted as a concept that has positive nuances.

The question then arises of what should be regarded as a risk. De-risking, often described as ‘small yard, high fence’, is assumed to narrow down what may be considered risk and seek strict regulations against them. In particular, the concept emphases areas related to economic security, such as ensuring energy and other scarce resources, protecting high-tech industries and advanced technologies, and stabilising supply chains. Therefore, de-risking is closely related to economic security.

The background of these two distinct concepts is reflected in the differences in how China is viewed by the United States and Europe. In the ‘National Security Strategy’ released in October 2022, Washington identified Beijing as the only competitor to reshape the international order, seeing China’s economic and military rise as a real threat to America’s preeminent position.

Europe, on the other hand, not only views China as a competitor but also paints a more complex picture. ‘EU-China – A Strategic Outlook’ released by the EU in March 2019, depicts China as a cooperating or negotiating ‘partner’ for the EU, an ‘economic competitor’ and a ‘systemic rival’. These complex views of China have been passed on to various policy documents in the EU and its member states. The European Council’s conclusions on China at the end of June 2023 and Germany’s first Strategy on China released in July 2023 included similar statements. In this way, one could say that Brussels is seeking a different approach to decoupling because of growing concerns about economic security in its relations with China.

The emergence and spread of the de-risking concept

Based on such a complex image of China, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen briefly and publicly mentioned the concept of de-risking for the first time at the Davos Conference in January 2023. However, it was not until she delivered a speech in Brussels at the end of March, ahead of her visit to China, that the concept was fully brought into the spotlight, as she attempted to provide a more comprehensive account of de-risking.

First, she explicitly rejected decoupling from China, arguing that it was neither viable nor in Europe’s interest, and instead proposed de-risking as a new concept to guide Europe. In her speech, von der Leyen presented four pillars for implementing de-risking strategies towards China: (1) making the European economy and industry more competitive and resilient, (2) better using the existing toolbox of trade instruments, (3) developing new defensive tools for some critical sectors, and (4) alignment with other partners, including Japan. Regarding pillar (1), the EU depends on Chinese supplies of 98% rare earth, 93% magnesium, and 97% lithium. On this point, she kept in mind the case of Japan. As Beijing put so much pressure on Tokyo by threatening to halt rare earth exports to Japan in the wake of the Chinese fishing boat collision near the Senkaku Islands in 2010, von der Leyen feared the risk of a similar situation. Similarly, regarding (3), she identified the following five sensitive high-tech fields as important industrial sectors which should be protected from China: microelectronics, such as semiconductors, quantum computing, robotics, artificial intelligence, and biotech.

Along with such developments, Washington began to pay attention to the concept of de-risking in April 2023, with Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan mentioning that the United States is aiming for de-risking from China rather than decoupling. Following this, the G7 Hiroshima Summit held in May declared that they would pursue economic resilience and economic security in relation to China based on the concept of de-risking.

Economic security initiatives by the EU

How is this concept of de-risking reflected in policy? As mentioned previously, de-risking is closely related to economic security. Even before this concept came about, problems related to economic security gradually became more apparent in the EU’s relations with China, requiring Brussels to address them.

The first problem is foreign direct investment screening. In 2016, the German industrial robot manufacturer Kuka was acquired by China’s Midea Group (called the ‘Kuka Shock’). Kuka possessed advanced technology that could be diverted to military use, and the Obama administration of the United States was also wary of the possible leakage of that technology. However, the German government and the European Commission cleared the takeover, saying that they saw no security threat.

One thing this dramatic acquisition made clear was that the EU lacked a framework for regulating foreign investments for reasons of security and public order. While the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS) plays this role in America, only 12 of the 28 EU member states had screening mechanisms in place at that time. Moreover, each member state implemented a different screening methodology, with no coordination to review investments which may impact multiple countries across borders in Europe. Faced with such a situation, the European Commission drafted a new investment screening framework in September 2017 which integrated these divergent screening standards among EU member states and enabled Brussels to introduce more rigorous checks and reviews on applications for acquisitions, especially in the high-tech, defence, and energy sectors, with reference to security and public order concerns. This framework came into force in October 2020.

The second is the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) for subsidies granted by non-EU countries. In principle, the EU prohibited subsidies from member state governments to specific companies to prevent distorting the level playing field in the EU market. However, there were no such restrictions on non-EU governments. In May 2021, the European Commission submitted a draft regulation that would authorise Brussels to conduct rigorous screening by requiring companies to give advance notifications and disclose information about whether they are subsidised by non-EU member states when entering the EU single market. This draft regulation came into effect in January 2023 and officially began to apply after the implementing regulation was adopted by the European Commission in July 2023. Although the FSR does not target specific countries, given that many Chinese companies receive subsidies from the Chinese government, it is expected that they will be subject to rigorous scrutiny because of this.

The third issue concerns the European Chips Act (ECA). The EU relies on imports from East Asian countries and the United States for much of its semiconductors and semiconductor products, with China playing an important role. In response, the European Commission drafted the European Chips Act in February 2022 built on the following three pillars: (1) the ‘Chips for Europe Initiative’, which aims to strengthen R&D, design and production capacities of semiconductors through public-private investment funds; (2) preferential treatment to ensure stable supply of chips by attracting semiconductor production facilities; and (3) monitoring semiconductor supply chains and crisis responses for any disruptions to the supply. The bill was adopted and enacted by the Council of Ministers in July 2023 and will come into force upon publication of the Act in the Official Journal of the European Union. Accordingly, the EU is attempting to increase its global share of semiconductor production from the current 10% to more than 20% by 2030.

The fourth category relates to economic security strategies. In June 2023, the EU released its first ‘European Economic Security Strategy’. It is not intended to specify China but to design the de-risking strategy of the EU as a whole, with the aim of promoting the competitiveness of EU industries, protecting European economic security by tightening restrictions on investments and exports, and partnering with like-minded countries. Based on this strategy, the EU will identify and thoroughly assess risks in the following four areas: supply chain resilience, including energy security; security of critical infrastructure; technological security and technology leakage; and weaponization of economic dependencies and economic coercion. This will lead to stricter restrictions on investment and export controls as required.

Brussels is now drafting additional measures related to economic security beyond the context of its relations with China. Among them are the ‘Critical Raw Materials Act’ (CRMA), which is designed to ensure stable supply of critical raw materials by securing, mining, and expanding production of important resources; the ‘Net-Zero Industry Act’ (NZIA), which aims to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and stable supply of diverse energy (both bills were submitted in March 2023); and the ‘Anti-Coercion Instrument’ (ACI), which incorporates various measures against economic coercion (an interim agreement was reached by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers in March 2023).

What these measures underlie is the notion that Europe should fundamentally reexamine the growing risks of unhealthy and disproportionate external relations, including its relationships with China and enhance its economic independence and resilience. This is partly influenced by the idea that China should be seen as a security threat to Europe, and China can be considered one of the main targets of Europe’s de-risking strategy. However, it is more important to avoid jeopardising the EU’s economic survival and economic growth because of its reliance on a few specific countries for resources and raw materials. In this respect, one can argue that it differs from the US, which is inclined to emphasise security threats in its strategy.

Seeking cooperation with other countries

How then does the EU cooperate with its G7 partners and other countries on de-risking?

First, to diversify its trading partners for important resources and raw materials, the EU is expanding its network of free trade agreements (FTAs). More specifically, Brussels is negotiating mainly with Australia, New Zealand, India, ASEAN, and MERCOSUR (the Southern Common Market of Latin America), with whom it has no FTAs. Furthermore, the EU has already signed an FTA with Mexico and Chile and is negotiating revisions to make them more comprehensive and up-to-date.

Moreover, vis-à-vis Japan, the Japan-EU High-Level Economic Dialogue convened at the foreign and economic minister levels after the EU released its European Economic Security Strategy in June 2023. In this dialogue framework, economic security has been discussed as one of the main agenda items, and Tokyo and Brussels have sought cooperation on economic security by exchanging the security concerns of Japan and the EU through mutual consultations. At its June meeting, Japan positively evaluated the EU’s economic security strategy, notably discussing responses to economic coercion, the buildup of resilient supply chains, export controls, and investment screening.

In July, the Japan-EU Summit Meeting was held in Brussels between Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, President of the European Council Charles Michel, and President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen. In terms of economic security, they discussed coordinating to build resilient supply chains, reducing strategic dependencies, and responding to economic coercion. They also signed the Memorandum of Cooperation on Semiconductors, which aims to enhance collaboration on an early warning mechanism for the semiconductor supply chain and cooperation in the research and development of semiconductors.

At this stage, as the EU’s cooperation with other countries for de-risking from China has just begun, it is still difficult to explore how this cooperation will continue. However, in these circumstances, the perception gaps on China remain a problem between them. Undeniably, Japan, the United States, and Europe have different views on various matters pertaining to China. In April 2023, French President Emmanuel Macron said that Europe should not be embroiled in the US-China confrontation over the Taiwan Strait. Macron himself did not downplay the Taiwan Strait issue, but his intention was to say that Europe should maintain its diplomatic autonomy even under growing US-China tension. However, this statement was subsequently met with several criticisms. Regarding de-risking, it is necessary to limit the scope of what should be considered a risk. Hence, it is necessary to repeatedly check, build upon, and share views on the risks they face related to China. Moreover, as Japan has close geographic and economic ties with China, Japan could cooperate with the EU in terms of de-risking China on many fronts.

Translated from “Oushu: Keizaiteki jiritsu-senryaku tositeno derisukingu (Europe: De-risking as a strategy for economic self-reliance),” Gaiko (Diplomacy), Vol. 81 Sept./Oct. 2023, pp. 48-53. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [January 2024]

Keywords

- Hayashi Daisuke

- Musashino Gakuin University

- Europe

- EU

- China

- de-risking

- decoupling

- G7 Hiroshima Summit

- economic security

- economic resilience

- economic self-reliance

- supply chains

- raw materials

- energy security

- technological security

- European Commission

- Ursula von der Leyen

- foreign investment

- European chips act

- FTAs