The future of Japan and ASEAN: Closer cooperation to address shared challenges

Over the past 50 years, Japan’s position has changed, but the economic and political relationship between Japan and ASEAN has grown closer and more trust-based. As partners navigating an uncertain future together, the importance of international cooperation between Japan and ASEAN continues to grow.

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Key points

- Rapid growth with coexisting developed- and developing-country challenges

- Shifting to a mindset that prioritizes sustainability and equity

- Concern over the low number of Japanese young people studying abroad in Asia

Endo Tamaki, Professor, Saitama University

2023 will be the 50th Year of ASEAN-Japan Friendship and Cooperation, and a summit meeting is scheduled for December in Tokyo. Over the past 50 years, the relationship between Japan and ASEAN, as well as Asia’s economy and society, has changed significantly. Asia’s rapid economic development has progressed while economic interdependence within the region has deepened. After World War II, Asia was known as a region of poverty and stagnation, but it has shown what has been called a “miracle” of high economic growth and has emerged as an emerging Asia, despite facing several crises. In the 21st century, the GDP share of Asia, including China, has surpassed that of the United States and Europe, and has become the center of economic development, transforming from a region that follows the lead of developed countries to a region that is a production base and a source of innovation. At the same time, risks and crises originating in Asia are having a serious impact globally. Although there are large disparities between countries, ASEAN countries have also joined the ranks of middle-income countries. In the 2010s, not only Singapore, but also Thailand and Malaysia transitioned from being recipients of direct investment to becoming investing countries.

Japan certainly played a leading role in the 20th century. Until the early 1990s, Japan generated 70% of East Asia and Southeast Asia’s GDP, and its nominal GDP was approximately eight times that of ASEAN10. However, this aspect has already changed significantly since the beginning of the 21st century. GDP per capita was surpassed by Singapore (2010) and Brunei (2011) (the latter varies depending on the period). The IMF predicts that ASEAN’s combined GDP will exceed Japan’s in 2026. At the level of individual companies and industries, competition is taking place that cannot be understood based on national hierarchies of developed and developing countries. For example, new services utilizing digitalization are emerging or developing faster in ASEAN countries (exemplified by companies like Grab in Malaysia and Go-jek in Indonesia). Innovations led by companies in emerging countries such as Thailand’s CP Group (Charoen Pokphand Group Co., Ltd.) are attracting attention. The transition from the era of “catch-up” to “leapfrogging” development will be further accelerated by digitalization. This is because ideas, not just capital and technological capabilities, are the source of competition.

The remarkable development of ASEAN countries will continue in the future. However, looking ahead to the next 10 years, and even 50 years later, it is not possible to be optimistic. This is because each country faces complex challenges and risks that cannot be effectively resolved without a change in thinking.

First, the emerging economies of ASEAN have not only developed at a rapid pace, but have also experienced “compressed development.” As a result, they are facing a more complex situation than Japan experienced in the past. For example, their birthrates are declining and aging at a faster rate than Japan’s, before they have fully developed their social security systems. This kind of compression of “time” can also be seen in the urbanization process of emerging ASEAN countries. As infrastructure and other connectivity accelerated across emerging countries, similar social transformations occurred across the region. Consequently, a situation has emerged in which both developed and developing country-type issues coexist within each emerging country. An illustrative example is the labor market, which succinctly encapsulates this dynamic.

In the labor markets of emerging countries such as Thailand, the number of white-collar workers and global elites is also increasing. However, since the 1997 Asian financial crisis, some countries have already introduced a non-regular employment system similar to Japan. On the other hand, the “informal economy,” a phenomenon that was thought to be unique to developing countries and one expected to disappear someday if they developed, still remains on a large scale today. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), approximately 60% of workers in Southeast and East Asia are engaged in informal employment. The number of gig workers, known as the digital version of the informal economy, is also increasing rapidly. Furthermore, like in developed countries, unemployment among university graduates has become a social issue, while there is also a serious shortage of workers in the field called 3Ds labor (dirty, dangerous and difficult). For example, Thailand employs 3 million foreign migrant workers (workers from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos), about 10% of the working population.

Second, the preconditions that made Asia’s rapid development possible are being shaken. In Asia 2050 (published in 2012), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) set out the conditions for Asia’s steady prosperity (including avoiding the middle-income trap). These conditions include: (1) the maintenance of peace in the long term and the absence of serious conflicts and political conflicts, (2) open global trade and stable financial systems, and (3) effective international cooperative action to address climate change. ADB noted that these three will be essential. Needless to say, all of these conditions are shaky.

The stability of an era that prioritized economic development while deepening interdependence within the ASEAN region has been shaken, and the “era of politics” is returning. In addition, there is a strong possibility that changes in “society,” such as the declining birthrate, aging population, and natural environmental conditions, will become more of a limiting and defining factor for economic development. The difficulty in Asia is that the factors that have promoted growth are also the causes of widening inequality, environmental problems, and human rights issues.

Third, various crises are making Asia’s future even more uncertain. As many international organizations have pointed out, Asia has a high disaster frequency and scale. In fact, environmental risks such as land subsidence in megacities, cross-border smoke pollution, and frequent disasters are pressing threats for many countries in Southeast Asia.

The frequent occurrence and compounding of crises within and outside the area, such as the coronavirus pandemic, disasters, and conflicts, make it difficult to steer policy management. Emerging economies need to deal both with peacetime issues and emergency responses to crises, political tensions (security, etc.), the expansion of social spending (social security systems and education), and other challenges, all at the same time. In the face of financial constraints, limited resources must be allocated to multiple issues that are sometimes trade-offs. Increasing uncertainty can lead to financial constraints on the selection of policy instruments for medium- to long-term challenges.

◆◆◆ ◆◆◆

Over the past 50 years, Japan’s position has changed, but the economic and political relationship between Japan and ASEAN has grown closer and more trust-based. As partners navigating an uncertain future together, the importance of international cooperation between Japan and ASEAN continues to grow.

To tackle Asia’s complex challenges, first of all, a bold shift in thinking is required. We need to seriously consider not only the “economy (efficiency and growth),” but also the balance and trade-off between the three value axes of “sustainability” and “equity.” At the same time as tackling urgent issues, it is also important to take a backcasting perspective, thinking about the present from the perspective of the future 50 years from now. It is also necessary to envision a stable society with a high level of well-being for people and regions from a long-term perspective. In that case, not only post-event responses and strengthening resilience, but also preventive and mitigation efforts will be crucial. Multifaceted thinking that combines short-, medium- and long-term strategies is required to respond to issues ranging from political conflicts to environmental problems and equity.

Second, Japan shares many challenges with ASEAN, but it has not yet found effective solutions as a leading country in addressing these challenges. In cases of global phenomena that occur simultaneously, such as the gig economy, ASEAN countries are responding more quickly than Japan. It is not always possible to apply Japan’s past experience, so we must find new solutions through mutual learning.

Third, looking toward the future, the key lies in securing and supporting channels that accurately reflect the perspectives of young people. The author places equal importance on a mock conference involving Japanese and ASEAN university students (Model ASEAN Meeting Plus Japan and JENESYS2023), conducted in Indonesia and Japan, as on the summit meeting. The phenomenon of compressed development has not only compressed socioeconomic development and transformation but also “experience” between generations, resulting in a generation gap in social awareness that is more substantial than older generations may think.

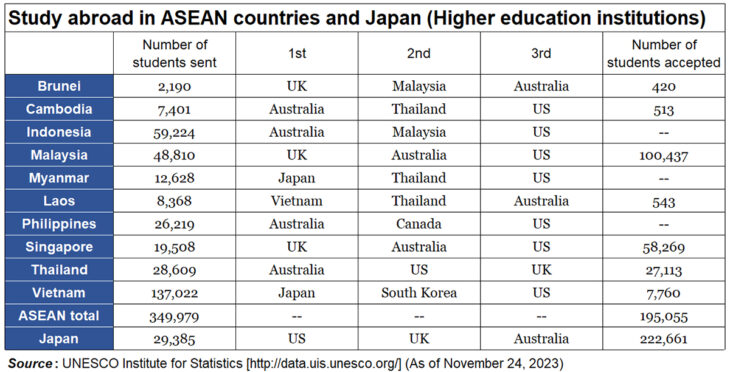

The young generation will be the key bearers for the future 50 years from now. According to data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), approximately 350,000 ASEAN students are pursuing higher education abroad, not only in Europe, America, and Japan but also within the ASEAN region itself, where the number of students studying abroad is on the rise. According to the same data, approximately 30,000 people from Japan study abroad. For reference, according to the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) (2019), approximately 25,000 people from Japan study abroad (for 3 months or more), and only 20% study abroad in Asian countries. Japan’s figures are not encouraging at a time when it is necessary to think together with the youth of Asia. It is also worrisome that there is a lack of opportunities to think about and discuss contemporary Asia, even in higher education.

ASEAN remains a highly diverse region. Beyond economic perspectives such as investment destinations and consumer markets, it is important for Japan to create mechanisms to deepen relations through exchanges not only among nations, but also among diverse actors in various phases.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 8 December 2023 under the title, “Nihon to ASEAN no Mirai (II): Kyoyukadai kaiketsu e renkei kinmitsuni (The future of Japan and ASEAN: Closer cooperation to address shared challenges),” The Nikkei, 8 December 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Endo Tamaki

- Saitama University

- ASEAN

- ASEAN-Japan

- Asia

- economic development

- compressed development

- emerging economies

- developed countries

- developing countries

- informal economy

- gig workers

- unemployment

- inequality

- era of politics

- crises

- sustainability

- youth

- generation gap

- higher education

- study abroad