Global Trade Reconfiguration in the Election Super Year

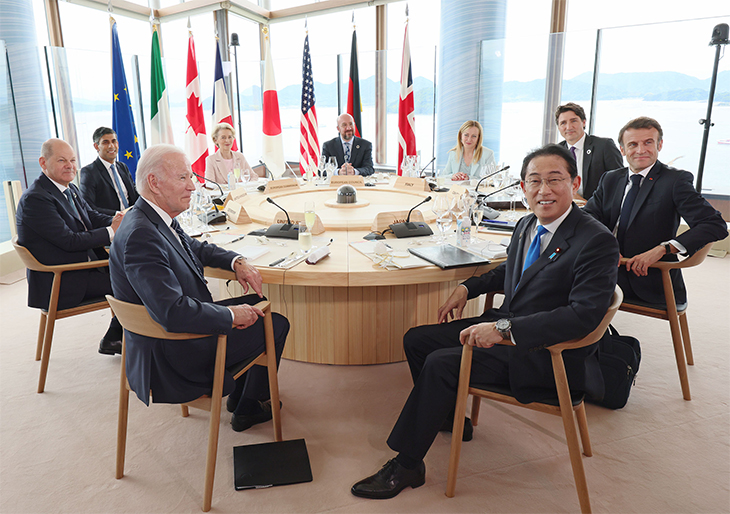

In their communiqué for the 2023 Hiroshima Summit, G7 leaders advocated concrete measures to “coordinate our approach to economic resilience and economic security that is based on diversifying and deepening partnerships and de-risking, not de-coupling.” It was an expression of determination to address global issues, but what should Japan do in the Election Super Year and beyond?

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Ito Sayuri, Executive Director, Economic Research Department, NLI Research Institute

Since the end of the Cold War, supply chains have expanded globally, and there are concerns about fragmentation due to multiple factors, including the escalating conflict between the United States and China, the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the climate crisis. At the G7 Hiroshima Summit in 2023, de-coupling was rejected as an approach to economic resilience and economic security, and a policy based on de-risking was affirmed. Friendshoring, the formation of supply chains among allied or like-minded countries; nearshoring, the relocation of business to neighboring countries; and reshoring and onshoring, the return of business to a country, became buzzwords to indicate the direction of restructuring supply chains.

Changes are already visible in global trade data. In 2023, the amount of trade between the United States, the European Union and Japan with China all decreased. From 2020 to 2022, the value of US imports was about the same as that of China and the EU. However, in 2023, while the decline in US imports from China slowed significantly, imports from the EU increased, widening the gap in import value. Imports from Mexico and ASEAN, especially Vietnam, also increased. In the United States, friendshoring and nearshoring appear to be occurring simultaneously. In the EU, intra-regional trade has a high share of around 60%. In addition, the trend towards friendshoring is clearly evident in extra-regional trade, as gas imports from Russia have had to be replaced by LNG imports from the United States and Norway, and imports from China have also declined. In Japan, exports to the United States are increasing to compensate for the decline in exports to China. Chinese statistics also show that trade with the US, EU and Japan has declined, reducing the country’s trade dependence on the West. The Global South is filling this gap and appears to be making progress in responding to environmental changes through diversification.

There are some points to keep in mind in order to determine whether these changes will become a sustainable trend and lead to both reaping the benefits of globalization and strengthening the supply chains.

First, the rise in the US share of exports from the EU and Japan and the decline in China’s share may reflect differences in economic conditions in the two countries rather than a realignment of supply chains. The US economy remains strong despite rapid and significant interest rate hikes and appears to be a “one-man winner.” On the other hand, China’s economy is becoming increasingly stagnant due to problems in the real estate market. However, it is possible that the economic ups and downs between the United States and China have been caused by industrial policies and corporate initiatives that encourage friendshoring, nearshoring, and even reshoring. These factors will need to be studied in the future.

Second, it is debatable whether the changes that can be identified from the statistical data will lead to the goals of strengthening economic resilience and security and de-risking. Exports and FDI from China are rising in Mexico and ASEAN, where US imports are rising. Criticism has been raised that the decline in US imports from China is simply a change in the flow from direct trade to indirect trade, and that there has been no change in the structure of the US dependence on China. Changes in trade flows for regulatory reasons rather than economic rationality lead to increased costs. The cost will be borne by the consumer. US citizens may be prepared to accept a certain amount of cost increases in order to strengthen the nation’s economy and strengthen its economic security, but the question is how much they can tolerate.

Third, there is also the question of the extent to which the government can intervene in the activities of private firms for the sake of economic security. Control of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) for the purpose of economic security is relatively easy to accept, and there will be little resistance to the development of defensive tools to protect technologies that may pose a security threat. However, there will be growing resistance to expanding the scope of export and outward FDI controls that constrain business activities and to intervening in overseas business. In the United States and Japan, conflicts between government and business over economic security have not become acute, but in Germany the relationship between government and large business over economic security has become strained. In Europe, there is growing concern about the deterioration of competitive conditions due to rising energy costs, rising interest rates, and the burden of stricter regulations to improve sustainability. Economic security seems to be reducing the momentum for reviewing supply chains.

The biggest problem may be the risk of destabilizing relations among allies and like-minded countries on industrial and economic security policies. Although the United States and the EU are closely linked through the activities of companies on both sides, they do not have a free trade agreement. Although currently on hold, there are also conflicts over subsidies to aircraft giants Boeing and Airbus and tariffs on steel and aluminum. Subsidy-based industrial policies, such as the “Bipartisan Infrastructure Act,” the “CHIPS and Science Act,” and the “Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)” in the United States, have raised concerns about industrial hollowing out in the EU, forcing the creation of a corresponding framework. On the other hand, the tightening of green and digital-related regulations promoted by the EU could also affect the activities of major US IT companies and Japanese companies. The EU’s “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)” to prevent carbon leakage also entered a transition period in October 2023. Expanding the scope will also increase the burden on allied and like-minded countries.

2024 will be the “Election Super Year,” with back-to-back elections around the world, including a presidential election in the United States and a European Parliament election in the EU. The politicization of Nippon Steel’s acquisition of US Steel is a move that indicates an “inward-looking” move to gain support for the presidential election. The risk is that the new post-election US-European regime will tend to look inward under the guise of economic security, leveling the playing field, and improving sustainability.

To prevent fragmentation from worsening, Japan must adopt the principle of “small yard, high fence” for economic security and strictly manage the narrow area that must be protected for security reasons. We must also firmly insist on not intervening in the activities of private companies without justifiable reasons. Japan should maintain an attitude that not only serves its national interests, but also aligns itself with the interests of the majority who support an open system.

Translated from an original article in Japanese written for Discuss Japan. [March 2024]

Keywords

- G7 Hiroshima Summit

- supply chains

- de-coupling

- economic resilience

- economic security

- de-risking

- friendshoring

- nearshoring

- reshoring

- onshoring

- trade

- United States

- EU

- China

- Japan

- imports

- exports

- industrial policies

- corporate initiatives

- Nippon Steel

- US Steel

- free trade

- Election Super Year

- inward-looking