Spirituality of Earthquake Disasters: Living with the Dead

Approximately 2.8 million sunflowers have been planted on 7.6 hectares of coastal farmland that was severely damaged by the tsunami caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake. This is one of many parts of the recovery process. The author says. “… the goal of reconstruction is the living survivors and visible things such as rebuilding roads and houses. The invisible dead and the feelings of the living toward the dead are excluded from the process.”

Photo: YAEZAKURA / PIXTA

Questions from the Great East Japan Earthquake

The results of my decade-long research on the Great East Japan Earthquake[1] were published on March 11, 2024 as Ikeru Shisha no Shinsai Reiseiron—Saigai no fujori no tadanaka de (Living dead—A spirituality of earthquake disasters amid the absurdity of catastrophe) (Shinyosha). The concept proposed in that paper, “Study of Spirituality in Earthquake Disasters,” is something I happened upon while working on the issue of those who died in earthquake disasters. One of the reasons I recognized the concept could be that I had previously been a member of a cemetery research group. But more than that, the Great East Japan Earthquake prompted me to ask myself the urgent question of whether I needed to think about death and the dead from the perspective of people who were suffering from the loss of loved ones. It’s not as if anyone close to me had died. In this essay, I would like to reflect on the deep relationship between the living and the dead, which I had previously had little interest in, but to which I was now forced to turn my attention.

It is well known that the Great East Japan Earthquake caused the largest tsunami in a thousand years since the Jogan Tsunami[2] of 869. At the time, I was teaching at Tohoku Gakuin University in Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture. I felt the shaking of the earthquake, and after confirming the safety of my students, immediately began to consider compiling a record of my experience of the disaster from the perspective of human history, even though the power and water supply were cut off. Published a year later, 3. 11 Dokoku no Kiroku ― 71-nin ga taikan shita otsu nami genpatsu kyodai jishin (Records of lamentations on 3.11—The great tsunami and nuclear power plant earthquake experienced by 71 people) (Shinyosha) was a 560-page, 500,000-character memoir in a climate where most books on the disaster at the time were photo albums and other records. Historian Irokawa Daikichi (1925–2021) commented that “the value of the book will remain in the history of the Japanese people because it was written by 71 victims who experienced the massive earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident with deep feelings immediately after the disaster” (book review, Kyodo News).

At the time of its publication, however, the main subject was the survivors themselves, and I had not yet thought to examine the relationship between the survivors and the dead. After the publication of 3. 11 Dokoku no Kiroku, a reporter asked me, “What is the difference between what the victims themselves write and what the researchers hear and write down?” In reality, the book was published in less than a year with the aim of recording the disaster before memories of it faded away, and since the three most severely affected prefectures (Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima) were too large to research, the only realistic option was to have the surviving family members of the victims write about the events of the disaster. However, when I asked the people who wrote the notes again, I realized that contrary to my original intention, they were trying to write things down as more than just a record. When I brought the finished book to them, they sometimes displayed it next to a funeral portrait or held it in their arms as if embracing a loved one. When I asked them why, their unique perspectives on life and death emerged.

“Pain Co-preservation Method” through memories

Many of the people who wrote memoirs responded that they were able to “sort out their feelings” or “felt a weight lifted off their shoulders” through writing. Some people were reluctant to seek counseling. “The reason I can’t move on is because I feel that if I go to counseling and get rid of this pain, the sadness and suffering will also go away. If I feel better after counseling, that means I will forget about my husband. I want to erase this pain and escape, but that (the thought that I am the only one who will be saved) makes me feel guilty, so I can’t move forward.” In other words, this woman felt a sense of guilt that although she would feel better if she received counseling, she would also lose her memories of her loved one.

There is a part of me that wants to feel better [be saved] and a part of me that thinks I shouldn’t be the only one to feel better [be saved]. For survivors of disaster victims who have such conflicting feelings, forgetting feels like leaving behind their feelings for the dead and saving only themselves, so they resist it as a solution. Before we started our research, we didn’t know that the idea of putting the dead before oneself was at the root of people’s hearts.

So the third way, what I call the “Pain Co-preservation Method,” has become very important in mental health care. This method is based on the idea that it is not always necessary to eliminate pain. For the bereaved who are resistant to forgetting, writing down the memories of their loved ones in a notebook and storing them semi-permanently outside of themselves leads to freedom from the burden and sense of responsibility. It is only by preserving the pain, rather than trying to eliminate it, that surviving family members can regain some measure of normalcy in their daily lives. A bereaved person who lost a son said, “I have to face each painful memory one by one (while writing), but it’s also a time to face my son, and strangely enough, I had the illusion that my son was beside me, but I was able to write the manuscript calmly.”

This is more than just “preserving love by not forgetting the dead,” it is a feeling that only bereaved families can understand. Quietly writing records alone became a joint effort with the deceased relative, or a “happy time” to talk together. Critic Wakamatsu Eisuke defines the dead as Kyodo suru Fukashina “Rinjin”(Invisible “neighbors” working together) (Wakamatsu, 2012), explaining the synesthesia of being invisible but certainly nearby. This is why I have not been able to talk about the earthquake disaster without mentioning the existence of the dead since then.

“Ambiguous loss” and ghost phenomena

During the Great East Japan Earthquake, connections with the dead other than blood relatives also emerged in a unique way. In the course of fieldwork for the joint university seminar on “Earthquake Disaster and the Dead,” encounters between taxi drivers and “ghosts” often became a topic of conversation.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, reports of ghostly phenomena continued to come in from various areas along the coast of the disaster zone. One of the students who investigated the urban area of Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, noticed that taxi drivers were having particularly strange experiences. While other spiritual phenomena were vague, such as hearsay or semi-confirmed information that “they may have seen a ghost,” the drivers’ experiences were concrete in that they had directly taken the spirit into their car and spoken to it. Moreover, instead of bragging about the events, they kept them a secret from their colleagues and families, and even paid the fares of “customers” who had disappeared along the way.

For example, one late night about three months after the disaster, a male driver named SK, who was 56 years old at the time, was waiting for passengers near JR Ishinomaki Station (Ishinomaki City) when a woman in her 30s wearing a winter coat got into the car even though it was early summer. When asked where she was going, she replied, “To Minamihama-cho.” At that time, most of the area was vacant. Suspicious, SK asked the woman, “It’s almost all vacant land over there. Is that okay? Why do you go to Minamihama-cho? Isn’t it hot to wear a coat?” When she replied with a trembling voice, “Am I dead?” SK was surprised and looked into the back seat through the mirror and said “huh?” but there was no one there. (From Kudo Yuka, Yobisamasareru Reisei no Shinsai-gaku [Earthquake studies of awakening spirituality]).

What we wanted to know was not whether ghosts existed or not, but people’s awareness of the phenomenon. When I asked him again, the driver said, “At first I was just scared and couldn’t move for a while,” but he also said, “It’s not so strange now. A lot of people died in the earthquake, right? It’s natural for some people to have regrets about this world. I don’t feel afraid anymore. If I see someone waiting for a taxi wearing out-of-season winter clothes again, I’ll treat her like a normal customer.”

Normally, when dealing with ghosts that have not yet reached the afterlife, people pray to send their souls to the “other shore”[3] by saying things like “don’t come out again” or “go to the other world.” However, here, beyond the question of whether ghosts really exist, the surviving family members of the deceased looked forward to their return with a sense of awe and quietly welcomed them. This was in contrast to the fact that many religious people tried to send the dead to the other shore with prayers for their souls, even as their families searched for the missing.

The Great East Japan Earthquake was a disaster that resulted in a rare number of missing people in recent years. In this sense, it can be said that the question of where to place the fixed point of death has been fundamentally questioned. Since the body cannot be identified, should they go back to the origin of the death event [the great earthquake], or a month later, or a year later, or should they not recognize death at all? Dr. Pauline Boss, professor emeritus of family sociology at the University of Minnesota, calls the situation of missing and uncertain loss “ambiguous loss.” It is a state in which the mourning of death is left half-finished, as opposed to a clear procedure of loss such as a funeral, burial, or cremation after death.

However, in the disaster areas, many of the surviving family members did not view their relationship with the deceased as a negative emotion. They accepted the ambiguous existence of the “living dead” as it is, without talking about their encounter with the dead to others, as a precious experience. The image that emerges here is of ghosts—those who have passed away in the past—being allowed to appear in the future tense.

Meeting the dead in a dream

The above was also seen in the dreams of the bereaved families. After the disaster, as the bereaved families began to sort out their relationships with their loved ones, we asked them to write letters to their loved ones. (Hiai ― Anohi no anata e tegami o tsudzuru [Tragedy and love—Writing a letter to you on that day]). In the letters, there were many descriptions of meeting deceased family members in dreams.

In general, dreams are backgrounded as inconsequential and unrealistic and fall outside the scope of sociology. However, the dreams described in the letters are mostly important thoughts that people want to convey to their deceased loved ones, and in that sense they constitute reality. Therefore, to exclude the content of dreams from sociology would have been to ignore reality. Therefore, I decided to interview the survivors and friends of the disaster and collect information about encounters with loved ones in dreams (from Watashi no Yume made, Ai ni Kitekureta [Even in my dreams, he/she came to see me]).

When I was collecting stories about dreams that disaster victims had, a strange thing happened. When I listened to students who had interviewed people about their dreams many times, I had to confirm whether they were really dreams or real stories. The line between their dreams and reality was unclear, and the dream world was so real that it could be perceived by their five senses.

It became clear that the bereaved families interpreted the revelations in their dreams as messages from the deceased, and by superimposing their own hopes on them, they transformed the dreams into wishes and made them real. In other words, they transformed the “dreams they had (while sleeping)” into “dreams they had in reality (daily life) (as goals)” and by superimposing them, they found hope.

For the bereaved, dreams are not something they can see with the intention of seeing them on that day, but rather take the passive position of being “shown” them. It is the deceased who are the main actors in reaching out to those left behind in this world, and a mysterious world unfolds in which warm communication continues even after death.

In the case of a disaster, the goal of reconstruction is the living survivors and visible things such as rebuilding roads and houses. The invisible dead and the feelings of the living toward the dead are excluded from the process. This leads to the collapse of our assumptions about time. In the process of reconstruction, people who lived in the past before the disaster are recognized as people who cannot live in the present or the future, their existence is erased from society, and they are forced to face a second death.

Once the heartbeat disappears from this world (first death), even the fact that one has lived up to that point is erased (second death). Catastrophes and the way of reconstruction are based on a modern time management that goes beyond individual logic, and we are unconsciously pushed into it. Dreams can be said to generate the power to negate this double death by freely “overwriting” and preserving the facts that occurred in the past. It is a clear antithesis to the distortion of reconstruction and the modern way of life.

The spirituality of the earthquake disaster for the living dead

After the worst natural disaster in a thousand years, even the religions [involved], who are usually experienced in dealing with the dead, were in anguish. One priest held many funerals after the earthquake, but because his own mother was missing, it took him four years to hold her funeral. “People can’t be drawn to something without something to pray to. It’s only because there is a heavy urn or a memorial plaque that people can easily enter into prayer” (Shinsai to Yukue Fumei [The Earthquake and the Missing]).

In other words, religious acts can only be treated in an institutionalized way as a clear loss if there is an object of worship, the body. In this earthquake, however, there were many cases where the body could not be recovered as a clear loss, so individual responses and relationships were called into question. One of the characteristics of the Great East Japan Earthquake is that many people were swept away by the tsunami and disappeared. The existing religious framework of worshipping the “other shore of the dead” and returning them to “this shore of the living” was insufficient to deal with the “unrested dead” who had no fixed place. That is, corrections were needed in a state of “ambiguous loss,” in which the living struggle to respond (connect with the dead) and are drawn into the afterlife, or in which enshrined souls move back and forth between this shore and the afterlife. Regular rites were not enough to comfort the hearts of families who suffered when the life of a loved one was suddenly interrupted. This is because the bereaved, unable to accept the death of a close relative, were forced to repeatedly “negotiate” individually between the deceased (the soul’s curse and consolation, the impurity of death and exorcism) and the afterlife, which still could not rest in peace.

However, this individual negotiation can also be seen as positive. A typical funeral proceeds quickly and without interruption, whether or not the surviving family members agree. On the other hand, in the case of a missing person, the absence of a body can be interpreted as a situation in which the bereaved can say goodbye to the deceased at a time that suits them. The understanding is that as long as they cannot accept the death of their loved one, they can keep him in an ambiguous state in their own world. In other words, it is now possible to perform a funeral ritual that one is satisfied with, while preparing oneself and having a proper dialogue with the deceased. Existing religions had the aspect of institutionalizing the sending of the dead to the other shore. On the other hand, in “ambiguous loss” we can find the seeds of individual religiosity, which differs from institutional religion in that each person seeks salvation in his or her own way, in accordance with his or her own feelings.

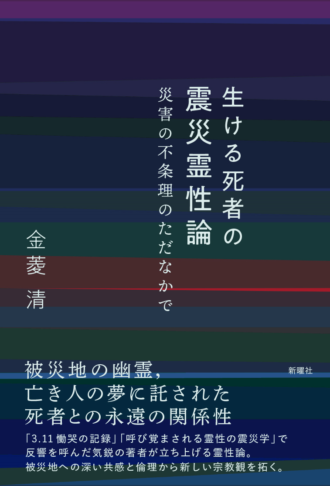

The author’s “Study of Spirituality in Earthquake Disasters” was published as Ikeru Shisha no Shinsai Reiseiron—Saigai no fujori no tadanaka de (Living dead—A spirituality of earthquake disasters amid the absurdity of catastrophe) (Shinyosha) on March 11, 2024, 13 years after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Photo: Courtesy of the author

Originally, there was a continuous transition between the other shore and this shore, but in the state of ambiguous loss, a gap is created and the “world of awai” is born (the spatial concept of “awai,” or the relationship that connects the other world and reality). A spiritual world in which the dead and the living intermingle is born. In a state where life and death are indistinguishable, various emotions arise, including a sense of guilt for “not being able to help” and a sense of gratitude that “the dead are with the living and helping them.” On the other hand, these conflicting emotions become a gift-giving relationship that becomes a support for living as the living respond and reciprocate, even though it causes suffering. This gift-like contractual relationship of intimacy with death is analogous to the “other world” of the Jomon period[4] (Kiyama, 2016) and was certainly present in our religious archaic strata. It has been denied in modern times, but it became clear in the recent earthquake. I have called this the Study of Spirituality in Earthquake Disasters and have clarified it.

This spirituality is not limited to the recent earthquake, but is also deeply rooted in traditional Japanese performing arts. Ghosts appear mainly in stories about curses and revenge. This belongs to the kabuki genre, such as Oiwa and Kasane[5], but noh is a little different. Yurei noh (Ghost noh) develops a gentle view of the dead and a story world of the “awai” between the dead and the living. The warlords who patronized noh were people who made a living from killing and feared curses, so they adopted and staged a gentle view of the dead, that “the dead are weak and suffer” (Imaizumi, 2009). According to noh performer Yasuda Noboru, ghosts are at the center of many noh plays, and by experiencing the mythical time of the ghost, who is the shite (the main actor), the audience can potentially go back in time and reset their lives as they live in the present (Yasuda, 2011). In other words, at first, the waki (actor opposite the main actor) unfolds with the flow of time (forward time) of the living actors taking precedence, but in the second half, the roles are reversed and a ghost (backward time) appears as the “shite.” In noh, ghosts initially look like normal “waki” people. However, when they appear for the second time, they wear masks and appear as ghosts in dreams. Ghosts, people from the past, enter the “here and now” under the guise of “now is long ago (long ago from the perspective of the present)” and a unique world unfolds. “Waki” become beings that connect this world with the next world by wandering around as people without a self. By meeting the other world, people can once again “live a new life.”

One bereaved family member said that through her dreams, “My feelings that I can die at any time haven’t changed, but when I meet my [deceased] son, I want to be a mother I’m not ashamed of.” Encounters with the dead, such as dreams and ghosts, encourage survivors to rebuild their relationships and lead meaningful lives.

Living with the dead

The “living dead” seen in dreams and ghosts, as well as in the notes and letters addressed to the deceased, have had a strong influence on the way the living exist. The existence of the “living dead” has created a way of thinking in the world we live in that does not require a strong and consistent subjectivity for the living, but allows us to live as weak, confused, passive, yet powerless subjects.

These efforts and reflections on the disaster over the past 13 years have been well received by people in fields other than sociology. For example, in the field of medicine and welfare, comments such as “Having the sensitivity to receive calls from the deceased is important in developing comprehensive community care” (Kamata Minoru, doctor and writer) gave me a hint for reconstructing the region, including the deceased. I have been studying the extremes of earthquake disasters from a sociological perspective, but I think the study of spirituality in earthquake disasters can provide new insights into the impasses and problems in other fields, such as medicine and the arts.

The study of spirituality in earthquake disasters also allows us to re-examine our view of life and death and the state of modern society. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as part of infection prevention measures, there were times when it was not possible to meet the dead and attend their cremations. As a result, it is still fresh in our minds that our ties with the dead were severed and they were turned into mere numbers, the number of deaths, and forgotten. The way the dead were treated during the COVID-19 pandemic is far from the view of life and death in which the dead live among the living as the “living dead,” and can be said to be an extremely stark demonstration of the state of modern society.

However, as I have shown in this paper, society is made up of the dead as well as the living. What the Study of Spirituality in Earthquake Disasters suggests for the present day is a re-examination of modern society and the way people exist, which are premised on a strong sense of subjectivity. Perhaps what is required of us today is to continue to listen to the forgotten dead, the silent others, the voiceless voices, and the living who are weak subjects, and to reconsider the state of society while sharpening our sensitivities.

References

Ikegami Yoshimasa, Shisha no Kyusai-shi ― Kuyo to hyoi no shukyo-gaku (A history of salvation for the dead—Religious studies of memorial services and possession), Kadokawa Sensho, 2003

Imaizumi Takahiro, Yurei-noh no Ichikosatsu ― “Kurushimu shisha”-kan no saiyo ni tsuite no oboegaki (A study of ghost noh—A note on the adoption of the view of the “suffering dead”), “Nihon Bungaku Shiyo” 79: 90 – 101, 2009

Kanebishi Kiyoshi (ed.), 3. 11 Dokoku no Kiroku ― 71-nin ga taikan shita otsu nami genpatsu kyodai jishin (Records of lamentations on 3.11—The great tsunami and nuclear power plant earthquake experienced by 71 people), Shinyosha, 2012

Kanebishi Kiyoshi (seminar) (ed.), Yobisamasareru Reisei no Shinsai-gaku ― 3. 11 Sei-to-shi no hazama de (Awakening spiritual studies of the disaster—Between life and death on 3.11), Shinyosha, 2016

Kanebishi Kiyoshi (ed.), Hiai ― Anohi no anata e tegami o tsudzuru (Tragedy and love—Writing a letter to you on that day), Shinyosha, 2017

Kanebishi Kiyoshi (seminar) (ed.), Watashi no Yume made, Ai ni Kitekureta ― 3. 11 Nakihito to no sore kara (Even in my dreams, he/she came to see me—After 3.11 with the deceased), Asahi Shinbun Shuppan, 2018 (Asahi Bunko, 2021)

Kudo Yuka, Shisha-tachi ga Kayou machi ― Takushi doraiba no yurei gensho (A town where the dead pass by—The ghost phenomena of taxi drivers), “Yobisamasareru Reisei no Shinsai-gaku (Earthquake studies of awakening spirituality),” Shinyosha: 1 – 23, 2016

Mogi Daichi, Aru Shukyo-sha wo Kaeta Nikushin no Shi ― Aimaina soshitsu no tojisha ni naru toki (The death of a family member that changed a certain religious person—When you become the party to an ambiguous loss), Kanebishi Kiyoshi (seminar) (ed.) “Shinsai to Yukue Fumei ― Aimaina soshitsu to juyo no monogatari (The earthquake and missing—A story of ambiguous loss and acceptance)”, Shinyosha: 93 – 108, 2020

Yasuda Noboru, Ikai wo Tabi suru Noh, Waki toiu Sonzai (Noh that travels to another world—The existence of the waki), Chikumashobo, 2011

Wakamatsu Eisuke, Shisha tono Taiwa (Dialogue with the dead), Toransubyu, 2012

Kiyama Soichi, Niraikanai no Genzo 3 (The original image of Niraikanai 3) “Yoronto Kuoria (Yoron Island qualia),” http://manyu.cocolog-nifty.com/yunnu/2016/07/810-4f54.html [in Japanese], 2016

Translated from “Shinsai Reisei-ron: Shisha to tomoni ikiru (Spirituality of Earthquake Disasters: Living with the Dead),” Sekai, August 2024, pp. 168–175. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [August 2024]

[1] On March 11, 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake occurred. As of June 20, 2011, the toll from this earthquake had reached 15,467 dead, 7,482 missing, 5,388 injured, 26,707 rescued, and 124,594 evacuated. 200,602 homes were totally or partially destroyed and 371,258 homes were partially damaged. Source: www.bousai.go.jp/kohou/kouhoubousai/h23/63/special_01.html

[2] In Jogan 11 (869), a magnitude 8.3 earthquake off the coast of Sanriku triggered a massive tsunami that surged several kilometers inland from the coast, killing more than 1,000 people. The affected area and scale are thought to be most similar to the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011.

[3] In Buddhism, this world, which is originally filled with earthly desires, is called “this shore.” In contrast, the world of the next world is called the “other shore.”

[4] The Jomon period, which lasted from around 14,000 BC to around the 10th century BC, corresponds to the Mesolithic or Neolithic period.

[5] Oiwa and Kasane are tragic heroines who appear in works by Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1755–1829), a kabuki kyogen playwright active in the Edo period (1603–1868), who portrayed each as a vindictive spirit. Each heroine was played by Onoe Kikugoro III (1784–1849), a kabuki actor of the time, who became very popular.

Keywords

- Kanebishi Kiyoshi

- Kwansei Gakuin University

- spirituality

- earthquake

- Great East Japan Earthquake

- tsunami

- disasters

- living

- dead

- survivors

- missing people

- ghosts

- Wakamatsu Eisuke

- invisible neighbors

- dreams

- memories

- bereaved

- guilt

- Pauline Boss

- ambiguous loss

- afterlife

- other shore

- awai

- religion

- sociology

- kabuki

- noh

KANEBISHI Kiyoshi, Ph.D.

KANEBISHI Kiyoshi, Ph.D.