A JOURNEY ALONG THE DESTROYED OKU-NO-HOSOMICHI (NARROW ROAD TO THE DEEP NORTH)

Takayanagi Katsuhiro

Not being able to offer even the nutrients of a slice of bread, nor the warmth of a single blanket, nor the usefulness of a single battery–this is what the words of poetry are all about.

In particular, haiku poems are like fragments of words, with just 17 syllables. In the face of the overwhelming reality of the earthquake and tsunami disasters, I could not just sit there and say that a haiku poet does not need to concern himself with this. Wasn’t there something I should do too, even though all I had was 17-syllable poems? Uncertain feelings swirled around in my head. But I could not find an answer, no matter how hard I tried.

I decided that I should ask someone. There was only one possible person to ask: Matsuo Basho, the great master of haiku poetry. “Oku-no-Hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North),” his major work, is a diary of his extensive travels, mostly in today’s Tohoku region, only covers a little less than 40 pages of 400-character manuscript paper. However, it is the crystallization of Matsuo Basho’s literature. The path he followed on the narrow road to the deep north overlaps with the areas affected by the earthquake and tsunami in many places. In particular, Matsushima is the place Basho thought of as the destination of his journey, as indicated by the statement “The moon in Matsushima lit my mind first” in the first chapter of Oku-no-Hosomichi, the departure chapter. Aside from Matsushima, places such as Sendai, Tagajo, Shiogama, Ishinomaki, Hiraizumi and other places where Basho stopped and composed haiku poems are said to have been terribly damaged. I decided to walk on foot through these places to appreciate the literature of Matsuo Basho, while at the same time imprinting on my mind what had actually taken place. I thought that by doing so, I might be able to find a clue to clarify what I should do next as a haiku poet. With this prospect in mind, I departed Tokyo on June 10.

Natori-gawa River: the seasonal words disappeared

After arriving at Sendai Station on a Shinkansen train, I took the Tohoku Honsen Line to Natori Station. In Oku-no-Hosomichi, Basho states “I arrived at Sendai after crossing the Natori-gawa River.” For this reason, I wanted to see the situation of the Natori-gawa River first. The Yuriage district on the estuary of the Natori-gawa River was totally destroyed by the tsunami, with scenes from there filmed and broadcast on TV many times. When I arrived at Natori, I found the usual suburban landscape in front of the station, to my surprise. A large discount store was operating in front of the station. Behind it, rice paddies and fields stretched extensively, with a few houses here and there. It was easy to find a taxi. However, this peaceful atmosphere vanished once I had crossed under the Sendai Tobu Road, about 1.5km from the station.

Natori-gawa River (photo by author)

There were toppled cars and boats lying in fields. Furniture fragments, pieces of metal, and other miscellaneous items could be seen among the debris. Brownish water was pooled in fields and rice paddies in many places. The taxi driver told me that the seawater had remained behind because the drainage pumps in the region were totally destroyed. The Sendai Tobu Road along the coast had functioned like a bulwark, stopping the flow of the tsunami there. This is why the areas in front of the station were safe.

The driver said, “You might not believe it, but the area has been cleaned up and things are now much better than they were.” Immediately after the earthquake, the roads and fields were completely filled with debris. After the debris was removed, the ground surface was exposed, reminding us that the tsunami had actually destroyed everything. When I got out of the taxi, a thick cloud of dust rose around my feet. The grey sand that covered the ground emitted a unique odor, a blend of the odors of raw fish and seawater. It must have consisted of the seabed sediments that were swept onto the land by tsunami and dried.

Debris removed from the town was piled up on the beaches. Uprooted pine trees were lined up neatly, waiting to be disposed of. I wanted to see the waves, but my view was blocked by the pile of debris. I found a small sandal in a pile, and noted “red sandal” in my haiku notebook. I found a sand hill and climbed to the top. The odor of seawater was strong, and white wave crests jumped before my eyes. I could not believe that the tranquil sea had transformed itself into a great tsunami and devastated the area. I took a photograph of the bindweeds that bloomed at my feet.

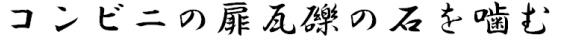

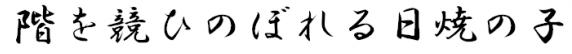

I returned to the taxi, and on my way back to the station, I wondered whether I could compose a haiku poem using “bindweed,” which is a seasonal word for summer. But nothing came to my mind, despite my efforts. It was the following haiku poem the came to me on the spot.

Haiku poems need to obey the rules of including a seasonal word and being composed of five-seven-five syllables. I was surprised to find myself composing a haiku poem without a seasonal word, which deviates from the rule, as if it were natural. I had always abided by the rule when creating haiku poems. Seasonal words have a long history, and a tremendous amount of time has elapsed with them. Take the seasonal word “cherry blossom,” for example. Behind this term is the history of enormous volumes of poetry that began with Tanka poems (in the Nara Period). The volume and substantiality of my predecessors’ works support haiku poems that only comprise 17 syllables. However, there are times when the historic nature of seasonal words does not prove valid in the face of overwhelming reality. Not valid might not be sufficient; I felt strongly at the time that history could even be a hindrance.

Mountain of rubble (left) and wooden grave tablets for the repose of victims’ soul (right) in Yuriage in Natori City (photos by author

A Mini Stop convenience store came into view through the taxi window. The store was crowded, and a woman at the cash register was taking care of the customers efficiently. Apart from the fact that the majority of customers were construction workers in work attire, the store was an ordinary convenience store such as those found everywhere in our daily lives.

I have never found the words Mini Stop (convenience store) so soothing. The name may be translated literally as respite. Although I only saw it for seconds from the taxi, the shop undoubtedly appeared as a respite after I had been shocked by the appalling reality that went beyond the imagination. There, I found a space for the steady daily lives of the people who are alive. The yellow and blue colors on a signboard that stood out in the desolate and monochrome landscape even appeared divine.

Konbini no tobira gareki no ishi wo kamuA convenience store is standing, with debris all around it. A pebble that had reached the entrance of the store is impeding the movement of the automatic door. It looks as if the surrounding debris was trying to enter the convenience store on its own will.

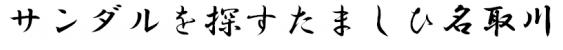

Then, another haiku poem came to me as if called forth by the previous one.

I am not sure whether the person who owned the sandals died or is still alive. But her soul must be searching for the other sandal.

Tagajo: shredded pine trees

I returned to Sendai Station from Natori Station and headed to Tagajo Station, several stations from Sendai, on the Sengoku Line. There, I was to meet Takano Mutsuo, a haiku poet living in Tagajo.

Black jeeps belonging to the Self Defense Force were lined up in front of the station. There was a banner reading “The 15th Brigade Okinawa,” indicating that they had been dispatched from far-away Okinawa. I asked a local man who walked by, and found out that the Self Defense Force had assembled a tent to house a bath, as no bathing facilities were available in the evacuation shelters. Recently, the city government had permanently leased a large-scale spa facility near the station, enabling people to bathe daily. As a result, the Self Defense Force had begun to withdraw a few days previously.

Takano arrived just in time, in a cool-looking polo shirt. Takano is the leader of the Koguma-za haiku group, which is based in the Tohoku region. He drove me to view the Port of Sendai, Gamoh wetland, Arahama region and other areas. In particular, I will never forget the pine forest at Shobuta-hama beach, a swimming beach.

In the Yuriage district, I had seen a large number of withered, copper-colored and uprooted pine trees. But the pine trees of Shobuta-hama were different from all of them. They were all twisted and shredded at the roots, as if a piece of paper had been twisted up. This would never have occurred without a tremendous force having been exerted in an instant. Takano said, “The force of the waves was tremendous,” and I could only nod.

Torn pine tree in Yuriage, Natori City (photo by author)

As he drove, Takano told me what had happened at the time of the earthquake. Fortunately, his condominium by a river had suffered only minor damage from the tsunami. However, life turned to chaos thereafter, because the life lines were interrupted. There was no running water, so he laid newspaper in the toilet, emptied his bowels, folded the newspaper and disposed of it himself.

“For a few days, I really felt depressed,” said Takano. “But after four or five days, we got used to the terrible situation,” he smiled.

I remembered the words of Dostoyevsky. “How strong people are when they are set to live their daily lives! Humans are creatures that adapt promptly to any situation.” Misery and pain are not the only reality in disaster-stricken areas.

As we drank together that night, Takano told me his thoughts about the haiku. There is a masterpiece haiku composed by a victim of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995 that is still being praised today. Takano hopes to compose a haiku poem that is equally distinguished, or rather, he feels that he must do so. Takano says that he is not obligated to do so for society. He believes that it is an obligation for himself.

I shared the thought that had been on my mind ever since the earthquake with Takano.

“I feel slightly guilty about composing haiku about the earthquake, because I was in Tokyo and only knew about the devastated areas through the reports on TV.”

Takano responded as follows.

“There are many types of victims. I have suffered relatively minor damage, while other people had painful experiences that have left scars that will remain for the rest of their lives. The majority of people must have undergone miserable experiences, but there could be some whose lives have turned in a positive direction due to the earthquake. Experiences are really diverse. The quake was felt in Tokyo as well. If your feelings about the disaster are serious, even if you have seen it only on TV, that is your ‘disastrous experience’ in your own way.”

Takano’s words soothed me. But I also felt that a similar attitude must be weighing on him. This was because Takano could have insisted that only haiku poets like him, who have suffered damage as a result of the earthquake, are in a position to speak about the disaster. But Takano does not wish to have the value of his haiku poems guaranteed by the fact that he is among the victims.

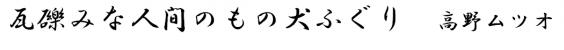

I recalled a haiku poem by Takano that was published in a magazine right after the earthquake.

All of the small chunks of stone and rubble were once part of something made by people. At the bottom of this poem lies grief over the fact that things that once supported human life and that were once cherished by people have turned into something we call “debris.” On the ground, the small, lovely flowers of inufuguri are blooming, as if they to caress those suffering a sense of loss.

Flower of Inufuguri

Note: Inufuguri, or Persian speedwell, is a weed often seen along the roadsides of Japan in spring. Its small, blue flowers cluster in groups, looking as if they are hugging the ground. It was given this name because its round-shaped berry looks like the testicle (fuguri) of a dog (inu). This humorous name adds to the familiarity of inuhuguri for the Japanese people.

Indeed, things that belong to nature do not turn into debris. Only things made by humans were destroyed and became debris. His viewpoint, which appears to do away with emotions, is indicative of his attitude that he is facing disaster as a human being, not as a victim. Persian speedwell that blooms in barren land is also mentioned, which I believe reflects his prayer for rebirth.

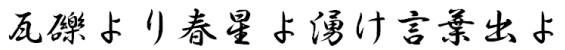

Here is my haiku poem, in harmony with his.

Note: Shunsei is a Japanese word meaning “stars of spring,” which somehow look as if they were shining in water due to the unique, moist atmosphere of spring.

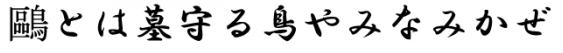

The following day, June 11, marked the elapse of three months since the earthquake. On that day, which saw drizzle commencing in the morning, I walked along a rainy road from Shiogama Station to Shiogama Shinto Shrine. I saw a group of people who looked like high school students in jersey athletic suits under the stone steps lined with huge cedar trees several hundred years old. The 202 stone steps are part of the main approach to Shiogama Shrine, and are noted as “Ishi no kizahashi kyujin ni kasanari (stone steps piling in kyujin)” in Oku-no-Hosomichi. Here, kyujin refers to an enormous height. The high school students climbed in pairs up the steep steps, which must have been slippery due to the rain, without being distracted. As soon as they reached the top, they immediately turned around and came down the steps at high speed. When I approached them, they saluted me with a “Good morning!” in voices clear enough to reach the heavens. I asked them which team they belonged to, and they told me that they were from the track team of Shiogama High School. They had recently recommenced their training, but could not use the school ground or facilities in the neighborhood because they had been damaged by the earthquake. That was why they were using the stone steps of Shiogama Shrine for training. While I was talking with them, I watched their sun-tanned, well-trained legs running at my side one after another. Did they know that the stone steps they were using for their training were the historic ones noted in Oku-no-Hosomichi? But seeing them devoted to what they needed to do at present, I came to realize that the historic background was of no significance. The faces of those high school students, wet from sweat and the rain, lifted my spirits.

Stopped clock shows the

time when the earthquake hit the

area, taken near the Shiogama Shrine by author

Matsushima: the bridge had collapsed

Next, I headed straight to Shiogama Port. A sightseeing boat leaves from here to cross the sea to Matsushima. A woman wearing black-framed glasses at the ticket counter told me about the disaster before I could even ask her.

“Black waves flowed toward us a number of times. This office was also flooded, and we had a hard time drying out the pages of the documents.”

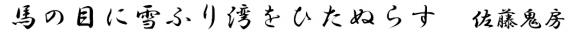

There was some time remaining before the boat was due to depart, so I walked along the path called Shiomo Alley. Monuments of literary figures associated with Shiogama lined the alley, but most of them had been uprooted, or become rusty due to the seawater. The following haiku was inscribed on one of them.

Sato Kibo is known as a stout-minded haiku poet based in the culture and climate of Shiogama. This is one of his best haiku poems, composed during the 1950s. I have always loved his haiku poems with their simple but romantic style, which are reminiscent of pictures for children.

But reciting his haiku poem here, the horse mentioned in the poem appears to be looking over the bay praying for the repose of the souls of the deceased. I could not help associating tears with the term “hitanurasu” (meaning continuing to fall on and make everything wet). Distinguished haiku poems may be appreciated anew, even after the elapse of time and in different settings. Even though the monument has fallen, the words inscribed on it are still alive.

It was time for the boat to depart. I was set to land in Matsushima, the destination of Basho.

Matsushima was filled with sounds.

Apart from the sound of the waves, there were the whistles of sightseeing boats, announcements inviting customers to visit restaurants, children screaming, sea birds crying, and even the cries of marine animals. Posters on the walls of many stores bearing the slogan “Go Forward, Matsushima” written in forceful brush calligraphy work also seemed to emit spirited calls for recovery.

It had been broadcast that the damage suffered in Matsushima as a result of the tsunami was relatively minor, because the numerous islands functioned as a buffer. But when I asked at a restaurant, the place had been flooded, causing all the electric machines to fail, and the shop had been forced to close for a while. Some of the souvenir shops in front of the gate of Zuigan-ji Temple still had their shutters closed.

I wanted to cross the water to Oshima Island, which is known as a sacred site. But all the walkways leading to the bridge were closed. I asked someone at the station about it, and was advised that Togetsu-kyo Bridge, the only bridge over which it was possible to reach the island, had collapsed due to the quake. Basho states in Oku-no-Hosomichi that Oshima is an island that continues from the land and reaches out to the sea. In reality, however, it is necessary to cross a bridge to reach the island. It was frustrating to find that I could not reach the island, even though it was right in front of me.

Basho is said to have composed a famous haiku that goes, “Matsushima ya Aa Matsushima ya Matsushima ya (oh Matsushima, Matsushima, oh Matsushima).” The fact is, however, that the popular comic poet Tawara-bo composed a similar poem (Matsushima ya sate Matsushimaya Matsushima ya), and this has been conveyed erroneously as a work by Basho. No haiku poem by Basho composed in Matsushima is mentioned in Oku-no-Hosomichi. In the departure chapter, Basho noted that the moon in Matsushima lingered in his mind more than anything. As can be seen, Matsushima was a place that Basho longed to reach. Why, then, did he not mention it in any of his haiku poems?

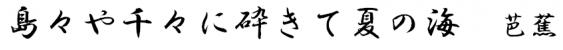

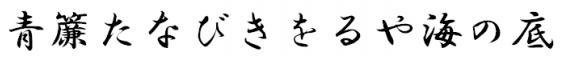

Basho once stated, “Our words are stolen in the face of a beautiful landscape and cannot be realized.” (“San-zoshi”) This means that our minds are swept away when we see beautiful landscapes, preventing us from composing poetry. In reality, however, Basho is said to have composed the following haiku poem in Matsushima.

Broken into thousand of places,

The summer sea.

Translation by UEDA Makoto, Matsuo Basho. 1982, Kodansha International

There is a countless number of islands, big and small, scattered in Matsushima Bay, and waves crash onto each of them. This can be described as waves crashing onto the islands, or the islands crushing the waves. It is a forceful haiku poem that provides a perfect depiction of the sea during the summer season, and I am personally very fond of it. But Basho appears to have thought that the haiku poem was not worthy of mention in Oku-no-Hosomichi, and he noted that he did not compose any haiku poems in Matsushima. Although the poem captures the nature of Matsushima Bay, which contains numerous islands, Basho must have considered that it did not capture the history of Matsushima that has been depicted in numerous tanka poems since the ancient days, or the accumulation of time behind the scenes. I feel overwhelmed by the spirit of Basho, who was devoted to poetry.

Matsushima Bay

Knowing that I could not cross the sea to Oshima Island, I walked to the beach opposite the island. It is the only sandy beach in Matsushima, with its rocky shore. Young couples were enjoying spending time on the sandy beach, and some of them had taken off their shoes and immersed their feet in the splashing waves. I sat on a log of driftwood and enjoyed the view of the waves for quite some time.

Note: Ao-sudare is a rush screen made of green bamboos. It is hung under eaves in summer to keep out sunlight and improve airflow in the house.

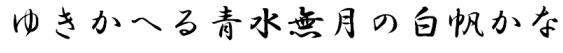

Note: Ao-minadzuki consists of “ao” for “green” and “minadzuki,” or “June” in the traditional calendar of Japan. June is called ao-minadzuki because green leaves grow thick at this time of year.

On that day, I traveled to Hiraizumi and stayed in a hotel there.

Hiraizumi: the light of a World Heritage site

The skies cleared beautifully the following day. Yaegashi Shiro, the Assistant Manager of the Construction and Water Supply Department of Hiraizumi Town Government, guided me through Hiraizumi. The town is located at the apex of a triangle formed by the routes of Oku-no-Hosomichi, and it is positioned as the pinnacle in the work. It is not hard to imagine that Basho had strong feelings for the location, as he was a fan of Yoshitsune. However, Hiraizumi was also seriously damaged in the earthquake.

“Golden Week turned out to be a nightmare. The number of tourists fell dramatically, to perhaps half the usual number of other years,” Yaegashi smiled bitterly. “We can’t really complain if we think about the disaster along the coast, and the damage we suffered does not seem like much. But roads have been blocked, as has the underground infrastructure. A lot more time will be needed for the restoration.”

Tabashine-yama Mountain

We followed the route that Basho took, and reached Takadachi. Setting aside the noise of the cars driving along National Highway 4, the landscape was superb, with the grand Kitakami-gawa River flowing slowly beyond the Tabashine-yama Mountain. I could see why Basho wrote, “I let tears fall as time passed by, holding my straw cap in place.”

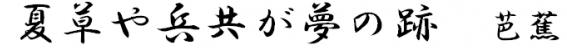

Next, we headed to the remains of Yanagi-no-Gosho at the foot of Takadachi. The recent excavations revealed evidence supporting the assumption that this place was the governmental office for the three generations of the Fujiwara Family, which is noted as “Hiraizumi-no-Tachi (Hiraizumi Mansion)” in Azuma Kagami, a text of the chronicles of events with the Kamakura Shogunate compiled in the 13th century. Basho noted in Oku-no-Hosomichi with regard to the landscape seen from Takadachi that the remains of the Main Gate must be found within several kilometers in the area. It is believed most likely that the remains of Yanagi-no-Gosho are the remains of the Main Gate referred to by Basho. Yaegashi said reluctantly that the white clover flowers covering the ground were to be removed. The flowers appeared to pacify the bloody history, and were too nice to be removed. In the remains, fossilized pollen of Poaceae plants, wild roses, Deutzia crenata and other plants have been found. The following is one of Basho’s best haiku poems, composed at Takadachi.

Of brave soldiers’ dreams

The aftermath.

Translation by Donald Keene, The Narrow Road to Oku

The summer weeds mentioned in the poem must have included these plants.

Some time before I departed on my journey, the news that Hiraizumi was to be registered as a World Heritage site, along with the Ogasawara Islands, was featured on the cover of newspapers nationwide. Yaegashi is one of the people who have made efforts over long years to have Hiraizumi registered as a World Heritage site. As we drove to Chuson-ji Temple, I asked him about the benefits of having the location registered as a World Heritage site. I expected an answer such as the fact that the economic impact would bring wealth to the region. However, he gave me an unexpected response.

“There isn’t any particular benefit. I just hope that the registration will enhance the identity and pride of the local people.”

During the 1970s, the Japanese Archipelago Reform Theory propounded by then Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei also affected the Hiraizumi region. According to the plan, land in the Takadachi region was to be cleared out on a large scale in order to build a national highway. It was the people from the local communities who had pleaded for the plan to be suspended in order to preserve the landscape.

“Even today, some people still believe in the ideas of Japanese Archipelago Reform. But we should be more strongly aware of the positive aspects of our land, rather than trying to copy Tokyo. I hope that registration as a World Heritage site will provide a starting point in that direction.”

The parking lot adjacent to the approach to the Temple was almost full. The location was crowded with numerous tourists, men and women of all ages. Yaegashi noted with a smile, “At last, things appear to have started recovering.”

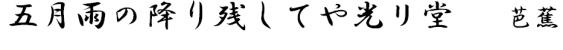

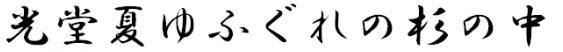

On the top of the mountain, I finally reached the Hikari-do (Konjiki-do) Hall, one of the major destinations of my journey.

At dusk in summer, when the heat gradually eases, I feel attached to the landscape around me. The Hikari-do Hall shining in the faint golden light behind the cedar trees, which have been growing there for hundreds of years, looks even more refined when seen at dusk. I felt as if the light will remain unchanged forever even as the human world constantly changes.

The Saya-do Hall that protected Hikari-do Hall when Basho visited the location was moved to a nearby site, and today a solid reinforced concrete building guards the crystallization of glory of the three generations of Fujiwara Family from the rain and wind. Amidst the great number of tourists that crowded the location, a girl in a wheelchair reached out as far as she could to drop a coin into the donation box set in front of Hikari-do Hall. Her mother stretched her hand from behind to tilt the box, and the girl was finally able to deposit the coin. Aside from the shine of the golden Hikari-do Hall, the subtle glitter of the silver coin she deposited also captured my imagination strongly.

The slope to the Konjiki-do Hall in Chuson-ji

temple. You can see the name of the hall

carved on the gravestone.

What could I do with poetry made up only of 17 syllables? Even since returning from my journey, I have not found any clear answer to the question I had in my mind when I departed. All I know is that I do not need to compose poems for anyone in particular. As a haiku poet, all I can do is believe in the strength of words and compose poems for myself. If the poems I compose happen to encourage or pacify someone, I should appreciate and celebrate that miracle. I will never forget the light I found in Hiraizumi, the last place I visited on my short journey.

At dusk in summer, when the heat gradually eases, I feel attached to the landscape around me. The Hikari-do Hall shining in the faint golden light behind the cedar trees, which have been growing there for hundreds of years, looks even more refined when seen at dusk. I felt as if the light will remain unchanged forever even as the human world constantly changes.

Translated from “Kuzureshi ‘oku no hosomichi’ wo yuku,” Bungeishunju, August 2011, pp. 134-141. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju Ltd.) [August 2011]