The Changing Flavors — and Drinkers — of Sake

The sake industry is booming — at least in one sense. Many of the varieties produced by small and medium-sized breweries have become hard to obtain. And what is notable is that sales of sake produced by the smaller breweries are being driven not just by middle-aged and elderly men, the traditional market for the sake industry, but also by women and young adult consumers.

The sake industry is booming — at least in one sense. Many of the varieties produced by small and medium-sized breweries have become hard to obtain. And what is notable is that sales of sake produced by the smaller breweries are being driven not just by middle-aged and elderly men, the traditional market for the sake industry, but also by women and young adult consumers.

This fact was conspicuous at the annual Wakate-no-Yoake (“Dawn of the younger generation”) sake-tasting event in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward October 2014, when more than 2,000 people gathered to sample the wares of thirty-one up-and-coming breweries, many of those visitors being women and young adults.

“We are seeing more and more young people and women attend these events every year,” says Watanabe Koei, president of the exhibiting Ippaku Suisei brewery, confirming the trend.

Events such as Wakate-no-Yoake, where visitors can sample a variety of sake brands and talk with the breweries’ representatives, have increased in number in recent years. Some of the events are targeted at women exclusively. The consumer environment surrounding sake is plainly undergoing a sea change.

“I’ve been working in this business for thirty-five years and this is the first time I’ve seen a situation like this,” says Hasegawa Koichi, president of Hasegawa Saketen, a producer and retailer of sake.

Against a background of declining consumption of sake overall, Hasegawa has worked tirelessly to extol the beverage’s virtues while also providing guidance to breweries on everything from taste to business management. In the meantime, Hasegawa has continued to open new stores and the chain now has outlets in numerous Tokyo locations including Tokyo Station and Omotesando Hills.

“The resurgence in sake today is due in large part to the efforts of Hasegawa,” says one young brewer. “At one time everyone in the industry sighed with the shared recognition that sake wasn’t something that would sell, but from last year the winds started to change direction. Sake has started to attract a lot of attention and things are now looking up for the industry as a whole.”

The trend is also apparent at Watami, a major chain of traditional Japanese izakaya restaurants.

“Just two or three years ago, sake appeared as something of a footnote on the menu,” says Product Planning Department manager Kikumoto Tetsu. However, in the spring of 2014 Watami revamped its menus and now displays varieties of good quality sake prominently on the menu, accompanied by photographs of the labels. The lineup included brews such as Dassai and Kuheiji that would delight lovers of sake [the offerings have since changed again].

Kikumoto argues the growing interest in sake comes in as a result of improvements to sake flavors and an increase in the younger sake-drinking population. Connoisseurs of sake have reacted with surprise, amazed at the fact that “an izakaya chain, and Watami at that, would stock such brands.” The offering has generated a buzz among consumers who are new to sake. “I now often see younger customers enjoying sake at our restaurants,” says Kikumoto.

While there has been a large drop in demand for the varieties of sake produced by the major breweries — the kind of sake found on the shelves of supermarkets and convenience stores — interest has grown in the varieties produced by family-run breweries and breweries which perhaps employ less then ten people. Such breweries are happily reporting that “production isn’t keeping up with demand” or that “inventory is being exhausted as soon as it’s created.”

That said, most breweries are not rushing to step up production to extreme levels. Many are taking a down-to-earth approach, saying things like, “we aren’t going to increase production any more than this,” or “even if we did increase production, it would be between twenty and thirty percent over the long term.”

Behind this conservative stance are painful memories of past failures of the sake industry.

Looking to a golden age while reflecting on past lessons

After peaking in 1973 at 1.5 million kiloliters, sake production has continued to decline, and today has fallen to less than a third of that level, at just 440,000 kiloliters. One of the big reasons the sake industry struggled with a decline in consumption lies in the pursuit of quantity over quality.

In a time when there were few varieties of alcoholic beverage and not as many choices as there are today, sake sold extremely well. As a means to handle the demand for increased production, a process of “dilution” that involved the addition of various raw ingredients was employed. As a result, consumers began to steer clear of sake, complaining of poor taste, a syrupy and overly sweet nature, or that it would cause headaches after consumption.

Although there used to be more than 2,000 sake breweries across Japan, most of them were operated under contract to major brewers, with the sake they produced provided to major brewers on a per-vat basis.

The end products of these major manufacturers demanded quantity over quality, and with subcontracting arrangements preventing the minor breweries in each locality from producing specialty varieties of sake, they lost fans.

After several booms surrounding locally brewed sake, circumstances began to change. From the mid-1990s in particular, distinct breweries have been popping up one after another across Japan.

This chain of events is not a mere fad. Behind the prosperity lies significant structural changes. The sake industry has entered its golden age.

Prosperity is No Fluke!

The Structural Changes that Occurred in Sake Production

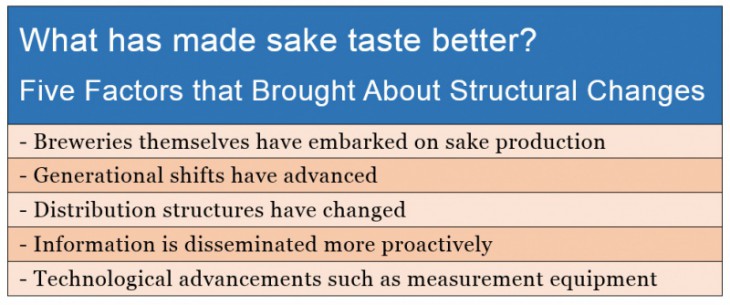

The recent popularity of sake did not just happen to coincide when better tasting varieties started to appear. The surge in popularity arises from significant structural changes that happened behind the scenes. Sake from new brewers has changed drinking scenarios and the demographics of drinkers themselves.

From a job in New York handling 800 billion dollars a day to the path of a sake brewer…

Aoshima Takashi, managing director and toji, or “master brewer” of the Aoshima Shuzo brewery located in the city of Fujieda, Shizuoka Prefecture, boasts the unique resume of working as a fund manager and then returning to the family business of sake brewing.

Aoshima’s method of brewing is stoic to say the least. For one thing, he spends half the year locked away in the storehouse. So committed is Aoshima that he shaves every part of his body, eyebrows included, as he goes about the brewing process, and this focus prevents him from going out.

He gets around three hours sleep a day, and avoids eating beef and pork because he says they dull his sense of smell. On top of that, Aoshima has no time whatsoever to check information from television, newspapers or the Internet, he says.

Then, for the remaining half of the year, Aoshima takes responsibility for growing the rice used as the raw ingredient for sake together with local rice growers. As no pesticides are used, he sets out early each morning to remove weeds from the fields.

Then, for the remaining half of the year, Aoshima takes responsibility for growing the rice used as the raw ingredient for sake together with local rice growers. As no pesticides are used, he sets out early each morning to remove weeds from the fields.

Aoshima has continued this lifestyle for almost two decades. Despite the abrupt change in lifestyle, going straight from glamorous finance work overseas to sake brewing, Aoshima says he thoroughly enjoys his work. “It’s not tough at all,” he laughs.

The sake produced in this way is shipped under the Kikuyoi brand. Kikuyoi goes down smoothly and tastes good. A popular variety with fans of sake, its stock is in short supply.

Aoshima makes sake in a way that wasn’t even conceived of a few decades ago, when there were clearly divided roles between the sake brewery as the operator of the business and the toji (master brewer) responsible for production of the sake. It was considered common sense that one role would have no say in the other.

For example, even if a son and heir returning to the family business after working for a major firm in Tokyo made the case for “making the flavor a little more refreshing,” the toji would not listen.

Toji are people who belong to a kind of technical group who work in agriculture in the summer and switch to brewing in the winter, and in Japan there are several schools of thought with respect to the techniques employed. Breweries would approach a toji union to dispatch a toji, but that didn’t always mean a skilled toji would be sent.

Under these circumstances, the brewery was not able to have a deep level of involvement or control over the end product.

Quality improved when the business operators themselves ventured into production

However, in the space of a couple of decades, the situation started to change in a significant way.

The young brewers taking over family businesses started to take over the role of toji and become involved in the production process.

Behind this movement was the strong desire of breweries to change the quality and flavor of their sake in the midst of the advancing decline of the sake industry as a whole, the narrowing financial leeway to hire toji amid worsening business conditions, and advances in brewing technologies that reduced the reliance on the intuition of toji.

By taking on the dual roles of management and production, a brewery’s policy could now be reflected directly in the sake brewing process.

Heirs to family brewery businesses noticed the increase in good sake and thought, “perhaps I should take over the family business after all,” setting off a chain reaction of heirs returning to their family breweries.

The resumes of the brewers who have embarked on production are varied. The industry is not filled entirely by people who have acquired their knowledge on the brewing course at the Tokyo University of Agriculture or by training at a brewing research institute. Some have learned on the job under the wing of a toji for two or three years. Some are humanities graduates and have worked for famous companies or record labels. There are freelance writers turned toji. And the work is not the preserve of men only.

Of course, there are also breweries producing famous varieties of sake using the traditional method of employing a dedicated toji. The wide range of breweries each with differing backgrounds and approaches has taken on the aspect of many flowers blooming in profusion. The taste of sake has undergone a dramatic transformation and diversification as a result.

At one time, excellent sake was regarded as having tanreikarakuchi (light, clear and dry) qualities. Even today, many customers at traditional izakaya restaurants will ask for a dry variety of sake.

This is because there was little diversity in the way sake was made, and there was a strong negative impression of the sweeter varieties being syrupy. Moreover, an acidic flavor was thought to be representative of lower tiered varieties of sake, because traditionally, the negative aspect of there being bacteria present in sake produced an acidic flavor. Today, sweetness and acidity are accepted by fans of sake, and these are the qualities that the new generation of breweries are challenging.

That is not to say, however, that these newer brews exhibit the syrupy sweetness or unpleasant acidity of their forerunners. They are infused with a clearer taste and a smoother fragrance and sweetness, and the acidic taste has also been added in a calculated way so as to complement western cuisine.

In addition to breweries embarking on sake production themselves, other structural changes have occurred in the world of sake (see Table).

Among them, the generational shift has had a large impact.

Most sake breweries are local personalities. For this reason, it has been common practice for one to take over the responsibility after accumulating some experience in the trade, and many toji were in their sixties or older.

However, breweries began to take on production responsibilities in addition to management, and a younger generation intent on changing the way things were done started to assume control of breweries.

Take Jikon, from the city of Nabari in Mie Prefecture, for instance. Among fans of sake, this is such a popular and hard to obtain variety of sake that many want to try it but cannot. The brewery itself produces the sake, headed up by Kiyasho Shuzo Brewery president Onishi Tadakatsu. At 39 years of age, he is a young brewer.

After graduating from Sophia University and working for a dairy product manufacturer, Onishi took over the family business a decade ago. At the time, the business was on the verge of collapse, he says. Given the circumstances, the brewery thoroughly reviewed their processes by doing away with the use of toji and producing the sake on their own. By also placing a focus on cleanliness, the quality of the sake also improved.

Then there is the Akita Prefecture-based Aramasa Shuzo brewery president Sato Yusuke, who is currently attracting the most attention in the sake industry as the flag-bearer of unconventional reforms. Sato is also just 39 years of age.

Sato, dubbed the “Steve Jobs of the Sake World,” basically loves new things. With experiments such as repurposing malt meant for shochu (a distilled Japanese liquor) production for sake brewing, or trying to brew in a way that actively reduces alcohol content, Sato is trying to completely change techniques for making sake that have stood for hundreds of years.

Sato has also joined forces with four nearby breweries in the prefecture to form a team known as NEXT5.

The NEXT5 members strictly evaluate one another’s creations, and meet to exchange technical information and hold discussions. All five members also hold events in efforts to disseminate information.

These information dissemination efforts are actually quite important. “Even compared with wine and shochu whose winemakers and brewers are based overseas, over the past two decades sake breweries have frequently held events in Tokyo and elsewhere. This has propped up the popularity of sake even as total consumption has declined,” says a brewer based in the Tohoku region.

In addition to events that attract hundreds of attendees, it is also common for popular brewers to take part in events organized by restaurants at which only ten or so people can gather.

Distribution has also changed. An increasing number of breweries are doing away with the conventional distribution that relied on wholesalers, instead visiting major liquor retailers in Tokyo with 1.8 liter bottles in hand and getting them to carry their sake directly.

Sake is inextricably linked with Japanese agriculture

With the taste of sake having changed dramatically and information dissemination efforts gaining momentum, the way sake is enjoyed has changed.

Sake used to go well with elements of Japanese cuisine such as sashimi and grilled fish, but with the emergence of sake varieties with stronger acidic and sweet qualities, it has also become a good match for meat dishes and Western cuisine.

Moreover, with different types such as those suited to being consumed during a meal or drunk after warming, as well as varieties with a refreshing taste or those that leave a strong aftertaste, choices can be made to suit the dish or the sensibilities of the drinker.

The opportunities to learn about this diversification of sake have increased through events and magazine coverage, leading to increased consumption on the part of women and younger drinkers. Wine enthusiasts have also begun to show an interest in sake.

Since the increased quality means sake can be enjoyed during meals like wine, there is interest in overseas expansion. In fact, there are many breweries thinking about expanding overseas.

At present, most of the popular breweries can’t even keep up with domestic shipments. There are also issues with storage if they were to ship products overseas in the future. Many varieties of sake need to be properly maintained at a constant temperature in refrigerators.

Most important is the cultural aspect. Wine is made by harvesting the grapes that serve as the raw ingredient right there from the vineyard. The basic premise is local production for local consumption, and this is ingrained into other cultures and environments. Many breweries are concerned that the practice of gathering together various raw ingredients and materials to make sake will evoke the image of an industrial product in the eyes of overseas consumers.

With this in mind, many breweries have started to place an importance on local procurement. In addition to water, some now procure rice that has been cultivated locally without the use of pesticides, and use locally sourced yeast.

Sake has always been a part of Japanese culture. It is closely linked with regional environments and agriculture.

“By drinking sake, you can contribute to Japanese rice cultivation and agriculture,” explains alcohol and food journalist Yamamoto Yoko.

While the rice acreage reduction policy will be abolished in 2018, even now, more than a million hectares of rice paddies are not being used.

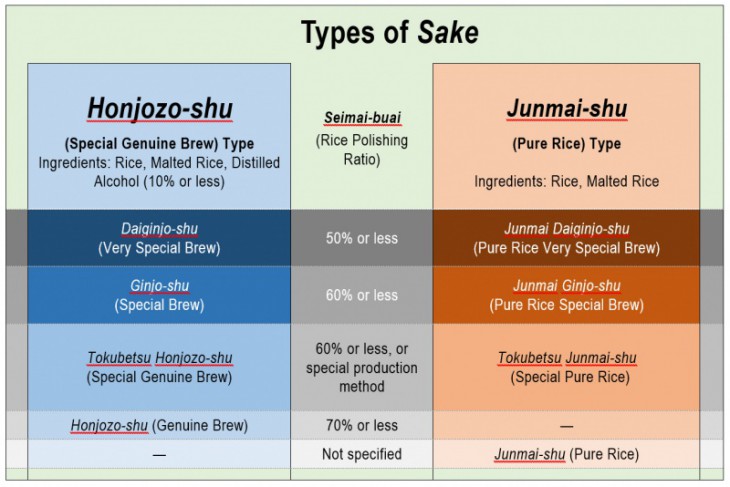

Three square meters of rice paddy is required to make a single 1.8 liter bottle of junmai-shu (pure rice sake). If Japanese people start to drink more sake and farmers start to cultivate more of the higher-priced shuzo kotekimai (sake rice) on idle farmland, Japanese agriculture and regional economies could be energized overnight.

According to Yamamoto’s calculations, if shuzo kotekimai was cultivated in all of Japan’s idle farmland to make junmai-shu, 3.6 billion 1.8 liter bottles could be produced annually. While this may seem an impossible number, if it were divided by Japan’s adult population it would correspond to thirty-six bottles a year for each person. In other words, one go (180 ml serving) a day.

If the rice were further scaled back to produce junmai-ginjo or junmai-daiginjo varieties instead of junmai-shu, the number of bottles would decrease further.

Although sake gets all the attention for its flavor, it is a drink closely linked with lifestyles and agriculture. I hope you keep that in the back of your mind the next time you tilt back on a serving.

Translated from “Kawaru Nihonshu no Aji to Nomite(The Changing Flavors — and Drinkers — of Sake)” and Kakkyo wa Guzen dehanai! Nihonshu-dzukuri de okita Kozohenka (Prosperity is No Fluke! The Structural Changes that Occurred in Sake Production” DAIMOND WEEKLY, November 1, 2014, p.52-53, 56-58. (Courtesy of DIAMOND, Inc.) [November 2014]