Edo and Tokyo as Viewed by Kobayashi Kiyochika, the “Last Ukiyo-e Artist”

Kobayashi Kiyochika is often referred to as the last ukiyo-e artist. Kobayashi goes by this name because he stuck to colored woodblock prints known as nishiki-e and kept pinning his hope on their potential until the end, despite the diversification and development of printing techniques in modern times. He must have had the pride of a defeated person because he was a vassal of the shogun born in Edo (present-day Tokyo). However, the innovativeness of Kobayashi and his importance as a modern artist stand out when we take away such frameworks associated with Kobayashi’s profile as an ukiyo-e artist.

Kobayashi as a vassal of the Shogun tossed about by the Great Transformation from Edo to Tokyo

We can learn how the young Kobayashi lived through the turbulent times from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period in Kiyochika jigaden (Self-portrait of Kiyochika), an autobiography he wrote in 1913 at the age of 66.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915) was born in a family of a low-ranked Tokugawa shogunate officials in a daimyo warehouse-cum-residence in Honjo. Kobayashi grew up watching his parents whittling bamboo swords and doing needlework late at night to make a modest living. The family home was lost as a result of the Great Ansei Earthquake in 1855. Kobayashi also saw people around him die in a cholera epidemic in 1858. Incidentally, Utagawa Hiroshige was one of the people who died in the epidemic. Utagawa, a master landscapist of Edo, passed away when Kobayashi was 11.

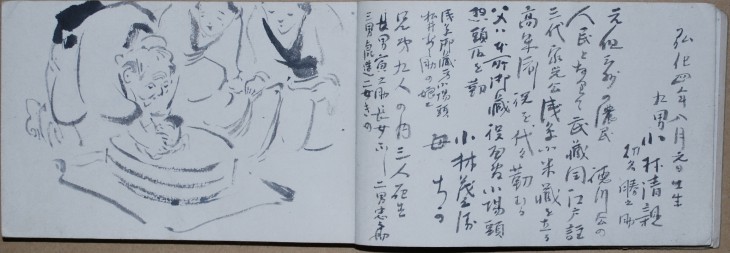

Sketchbooks

1878 to 1913/ privately owned

These books contain the accumulated sketches of Kobayashi. Ten of them remain today. The sketches include many watercolor designs from which Kobayashi produced his kosenga, such as Kudanzaka Satsukiyo (Night in May at Kudan Hill), which is introduced below.

Kobayashi lost his father in 1862, when he was 15. He succeeded his late father as the head of his family, even though he was the youngest of nine brothers. Accompanying Tokugawa Iemochi on a visit to Kyoto, Kobayashi stayed in the ancient capital and in Osaka in 1865. He witnessed street fighting in Kyoto in 1868 when he took part in the Battle of Fushimi. Kobayashi returned to Edo as a member of the defeated Tokugawa shogunate army, and witnessed the surrender of Edo Castle.

In addition to these sudden changes in society that Kobayashi experienced himself, the autobiography covers standard episodes that hint at his future, such as Kobayashi’s love of drawing from early childhood, his habit of sketching street scenes, and an incident in which he threw a model drawing back at a sketch artist in town because it didn’t portray bamboos and plums in a natural way.

The autobiography ends with Kobayashi being beaten by the high-handed members of the imperial army and burning sketches that he had made during the years of public unrest following Edo Castle’s surrender. Kobayashi appears to have started writing his autobiography with the original plan of sketching his whole life. However, his pen seems to have stopped there, possibly reflecting the mixture of his mettle as a vassal of the shogun and his thoughts on days gone by, such as his desolate feelings as a failure.

This is why we have no way of knowing something that is very important.

Following Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s order, Kobayashi moved to Shizuoka with many other vassals of the shogun in the subsequent period. However, Kobayashi returned to Tokyo suddenly in 1874, and made a sensational debut with his kosenga (light beam pictures) in 1876. The circumstances and the course of study that led to this debut remain completely unknown, however. Kobayashi is said to have had close exchanges with sketch artist Kawanabe Kyosai and lacquerer Shibata Zeshin, studied photography under Shimooka Renjo, and learned Western painting from Charles Wirgman, a correspondent and an illustrator for the Illustrated London News. However, no conclusive evidence has been available.

Kudanzaka Satsukiyo (Night in May at Kudan Hill), 1880

Privately owned (placed in the care of the Nerima Art Museum)

Kosenga were pictorial descriptions of noted places in Tokyo whose new sensitivity to the times and themes differed entirely from those of traditional ukiyo-e woodblock prints. What and from whom Kobayashi absorbed in a matter of just two years before the kosenga’s birth are points that are extremely interesting. However, Kobayashi himself offers no clues whatsoever. In the meantime, watercolor sketches, from which those light beam pictures were produced, remain in his sketchbook. We cannot overlook the fact that Kobayashi created these watercolors, whose level of perfection is too great to call them sketches. His mastery of expression, which compares favorably with that found in the watercolor sketches of his contemporaries, such as Takahashi Yuichi and Goseda Yoshimatsu, modern Western painting leaders in Japan who had a teacher-pupil relationship with Wirgman, deserves admiration.

Were ukiyo-e sketch artists aware of contemporary trends in Europe?

Kobayashi’s kosenga did not necessarily include lines showing the outer edges of the depicted items like those found in traditional ukiyo-e woodblock prints. His light beam pictures are characterized by compositions with color fields in which burs and gradations are frequently employed, and the accumulation of dots and meshes is reminiscent of copperplate prints and lithographs. Watercolors were necessary as conceptional drawings for sharing images in order to use woodblocks to express light and darkness, which change delicately over time, and the weather and atmosphere overflowing from the pictures, neither of which had existed before in the world of ukiyo-e woodblock prints that are produced through the joint work of craftsmen such as sketch artists, wood-carvers and printers. Making watercolor paintings must have been a great transformation in the process for producing ukiyo-e woodblock prints in view of the traditional role of sketch artists, which was to draw lines showing the outer edges of depicted items.

There is one interesting work that is believed to have been published in 1876, when kosenga made its debut. A man in a purple coat with his back to the viewer in this picture, called Ueno Koen gaka shaseizu (A painter sketching at Ueno Park), appears to be a painter. There is an item that looks like an easel in front of the man, with a white canvas on it. Under close examination, it is clear that the painter in the picture has a brush in his right hand and something that looks like a palette in his left hand.

Whether in the East or in the West, paintings were completed in studies as a matter of course, even if sketches were made outdoors. In the middle of the nineteenth century, painters who made sketches, colored them and finished the landscapes in the open air, or the so-called pleinairists, arrived on the scene in Europe.

There is no way of knowing whether the painter depicted in Ueno Koen gaka shaseizu was Kobayashi himself. It is not even certain whether a painter like this man actually existed. However, the knowledge of the approach and idea of setting up an easel and making color sketches in the open air bring into view an image of Kobayashi as a modern artist who was not bound by the frameworks under which ukiyo-e artists worked.

Kobayashi stopped creating kosenga suddenly in 1881. After that point, he produced works such as comic pictures, satirical drawings (published in Marumaru chimbun magazine) and pictures of the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. Kobayashi worked remarkably in each of these fields in ways that only he could. However, woodblock prints began to decline continuously from the end of the nineteenth century. This trend caused Kobayashi to leave woodblock prints and switch to original drawings. Kobayashi often visited a variety of provinces in the name of sketch trips. We can find his footprints in various parts of Japan, including Kansai, Shinshu and Hokuriku.

Kosenga produced by Kobayashi, who had withdrawn from the frontline, underwent reevaluation from the end of the Meiji period (1868–1912) to the first year of the Taisho period (1912–1926).

People often describe kosenga as depicting nostalgia for Edo, but that is not how these pictures were viewed at the time when they were published. This was the case because kosenga portrayed cheerful, proud scenes of a Tokyo full of things that were new and modern, such as rickshaws, locomotives, gaslights and telegraph wires. The assessment that light beam pictures depict nostalgia for Edo belongs to the second generation of authors in the Meiji period, who lamented over a Tokyo that had developed rapidly from Edo and kept nostalgia and yearning for Edo in their respective works. This view has its roots in the members of Pan-no Kai (the Pan Group), such as Nagai Kafu, a novelist who returned from his stays in Europe and North America, writer Kinoshita Mokutaro and poet Kitahara Hakushu. In particular, Kinoshita went to see Kobayashi with great glee after learning that the venerable artist who had produced these light beam pictures was still alive. This visit took place when Kobayashi was 66 and Kinoshita was 28.

There is one original drawing that Kobayashi is believed to have made in his twilight years. A bridge in this drawing, which is called Kaika-no Tokyo Ryogokubashi-no Zu (A picture of Ryogoku Bridge in civilized Tokyo, which is in the possession of the Ota Memorial Museum of Art), is the old Ryogoku Bridge built of wood before its substantial repairs in 1875. The bridge depicted here looks like the Ryogoku Bridge in Utagawa Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e works. The lights shown on the bridge could be oil lamps or gaslights. Streetlights are said to have come on over the Ryogoku Bridge considerably late in the Meiji Period. Another question is why Kobayashi, who had never given a title to his original drawing, titled the picture “civilized so-and-so” and drew an old bridge built of wood. We can detach this question and contradiction from the artistic activities of the young authors cited above and social trends. In other words, Kobayashi wanted to draw a nostalgic picture of the Ryogoku Bridge in a civilized Tokyo.

A big ship lays its mast low

And a boatman yells out

As the ship goes under the bridge of Ryogoku

Moist river winds of May 5 cool the skin

Waves toss about the gentle paddle beats of an early boat from four squares

And butterflies in workmen’s livery coats dyed with peonies

Kiku Masamune, an excellent sake from Nada,

Brings a nostalgic aroma to a sake cup made of usuhari glass

The sun’s dim departing rays arrive

From the second floor of a Western restaurant

Across the dreamlike round roof of the Kokugikan Arena

My heart loses its composure somehow

As I catch the shadows of birds flying far at sunset

Kinoshita Mokutaro, Ryogoku (1910)

This poem appears to have been created after the original drawing by Kobayashi. In this poem, we can understand how an old ukiyo-e artist, who was believed to have disappeared from the scene with the decline of woodblock prints, synchronizes himself sensitively with young artistic activities and trends.

In the meantime, we can point out similarities between this work, Kaika-no Tokyo Ryogokubashi-no Zu, and Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (1872 to 1875, in the possession of the Tate Museum in Britain) by James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), an American painter who worked successfully in Britain. In both of these works, mere shadows of people are depicted on an old wooden bridge near dusk. Both have a ship with warped bows like a gondola on a river and its boatman controlling an oar. Lights visible on the other side of bridge piers are depicted in many colors in both pictures, including blue, red and yellow. They both express lights reflected on the surface of the water with wavering lines. We cannot view these similarities as a coincidence.

Again, it is Kinoshita who links these two works.

The spacious canals nearby were green like the ground, and those in the distance shone white like silver.

A deep black shadow of a bridge like the one in Whistler’s painting, whose tone a painter might call purple ash or ash green, crosses the center of this picture. [Omitted paragraphs here.] The black shadows of men come and go on the Whistler-style bridge in patches. These shadows present their shapes distinctively like pine trees illuminated from behind by the setting sun, because green-gold lamplights that shine through the windows of a white-walled school located in the distance throw light on them as the shadows move close to the far end of the bridge.

Kinoshita Mokutaro, an excerpt from Rokugatsu-no Yoru (Night in June) (December 1909)

This verse describes the area around the Sumida-gawa river by citing Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge. We can also see the verse as a description of Kaika-no Tokyo Ryogokubashi-no Zu. Kinoshita had never visited Europe when he wrote these sentences. However, he referred to another painting by Whistler, made a comparison, and gave the poem its title. As these actions imply, Kinoshita must have viewed Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge by some means, including as a photograph or a block print. It does not surprise me that Kobayashi had the chance to do so.

It has been said since Whistler’s lifetime that Utagawa Hiroshige’s works had an influence on Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge. Inspired by this Whistler painting, Kaika-no Tokyo Ryogokubashi-no Zu was born, as if to conform to the viewpoint of keeping the eyes fixed on Edo and Tokyo.

It has not been recognized that Kobayashi, who is referred to as the last ukiyo-e artist and who had placed himself in a system for sketch artists, was among the first to learn watercolor painting, and that Kobayashi was able to gain a world of his own that is in tune with young artists in his twilight years. The very portrayal of Kobayashi as an ukiyo-e artist is another aspect that we must consider from this point on.

Translated from “Saigo no Ukiyo-e-shi: Kiyochika no Miteita Edo / Tokyo (Edo and Tokyo as Viewed by Kobayashi, the “Last Ukiyo-e Artist”),” Tokyo Jin, May 2015, pp. 128-132.

(Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [May 2015]