Nago City Hall: How did Atelier Zo Engage with Okinawa?

Nago City Hall, north side

Atelier Zo + Atelier Mobile (Team Zoo)/1981/Location: 1-1-1 Minato, Nago City, Okinawa Prefecture

In 1981, Nago City Hall was completed. Now, after 40 years, discussions are underway regarding rebuilding, including the possibility of relocation.

All photos by the author

Kamachi Fumiko, Representative, ConTon Architects

Architecture — Ashagi Terrace and Pillars

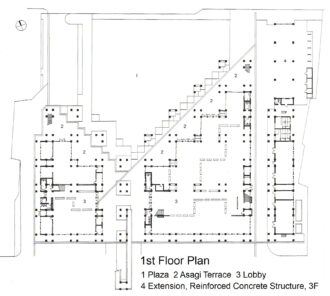

From 1972 to 1974, a 40-hectare area on the seaside of Nago City was reclaimed, and a national road was constructed to meet the deadline for Expo ’75. Nago City Hall was built facing this road. This City Hall has two faces. The north side faces the urban area and features the “Ashagi[1] Terrace,” which invites visitors with its stepped-back design both in plan and section. The south side faces the national highway and showcases a majestic facade with striped pillars and 56 shisa[2] statues (legendary beast statues of Okinawa often installed on roofs).

Drafted 40 years after the completion of Nago City Hall in 1981, the Nago Bay Coastal Basic Plan (2021) details consideration of renovations to the hall including its relocation. Currently, foundational surveys regarding these plans are being conducted. All shisa statues have been removed due to the risk of deterioration.

Visitors to Nago City Hall on weekdays may encounter various scenes: people having meetings on the Ashagi Terrace, towels swaying on the adjacent terrace, employees watering plants during lunch breaks or heading to the amahaji[3] (the deep eaves of Okinawan houses) washroom while brushing their teeth. Visitors from the urban area seem to be familiar with the layout, knowing which Ashagi Terrace entrance to use to access the building. Daily activities are not hidden but rather overflow, and the boundaries may be blurred. The distance between visitors and staff is close, and the city hall doesn’t appear overly formal.

In the Nago City Hall design competition, the question of “What should a City Hall be?” and “What is architecture in Okinawa?” were raised. The designs incorporated innovative approaches to climate and environment, reflecting contemporary design methods in Okinawa. Regarding the aforementioned Ashagi Terrace, “ashagi” refers to a detached room for visitors located in the front yard (mya) of the main building (ufa) of a traditional Okinawan house (it can also refer to a shaded space composed of stones and banyan trees). Ashagi Terrace, as its name suggests, is a space for visitors to the main building (City Hall).

The floor plan consists of separate Western and Eastern wings, designed with a double grid of 7.2 m and 2.4 m composite pillars. Within the 2.4 m square, there are either four or three pillars measuring 0.64 m square. In the Ashagi Terrace space, both the number and thickness of these columns are crucial, as without the pillars, the space would feel lacking. The challenge was to incorporate the culture of Okinawan stone culture into the construction of the space, using concrete blocks. The drawback is that upon entering the indoor area, the spacing of the columns in the double grid is wide, resulting in the loss of rhythm in the columned space.

The outer layer of the building, including amahaji eaves, “hana blocks[4]” (decorative concrete blocks), louvers and turf, appears to be designed based on their shading and insulation functions and the intended use of the space. However, the consistent design of the pillars, both inside and outside, is distinct. They are made of two-toned pink-and-gray laterally striped formwork concrete blocks, which I consider to be a significant expression of Atelier Zo + Atelier Mobile’s engagement with Yoshizaka Takamasa’s “Iuke-logy” (a coined word for his concept) in Okinawa.[5]

They confronted Yoshizaka’s Iuke-logy, which discussed the work for a new connection between humans and materials. In the process, they speculated on how to handle and present standardized factory-produced concrete blocks, which were becoming common in Okinawa. Rather than imitating Okinawa’s stone construction culture, it is inferred that the space has been reconstructed using three elements: “stone” (concrete block), “reinforced concrete,” and “plants.” Therefore, each block had to be painted separately instead of being treated as a large mass, and it was not acceptable to have them entirely white or entirely red. This spirit is consistent throughout every corner of this architecture. The louvers of Ashagi Terrace retain the shape of flat blocks, while the pillars and walls are created as blocks, maintaining their presence as blocks without filling the joints with plaster. Where does their sentiment for Okinawa come from?

The Three Principles of Autonomy and Regionalism

Atelier Zo’s engagement with Okinawa began in 1970, before the islands’ reversion from US control to mainland Japan in 1972. The company conducted thorough investigations of Okinawa on the eve of large-scale development using a “heuristic method” aimed not just at observation but also creative exploration. Their proposals for urban planning went beyond conventional approaches, and in the Okinawa Onna village basic concept (1972), they explicitly stated the village’s three principles of autonomy: (1) preserving the beautiful natural environment, (2) taking control of the village’s future in their own hands, and (3) improving living environments and infrastructure. After the reversion to mainland control, with Expo ‘75 as a catalyst, a wave of development for tourism sites surged, and while alternative proposals were put forward, deeming the provision of large-scale development sites undesirable. However, the focus on autonomy hit at the core of the issue. Tamanoi Yoshiro (1918–85) was an advocate of “regionalism” from an economic perspective who taught at Okinawa International University from 1978 to 1985. He defined “regionalism” as the residents of a specific region having a sense of unity with their community based on the region’s unique characteristics, and seeking the administrative, economic, and cultural independence of that region (Chiiki-bunken no Shiso [Idea of decentralization], 1977).

In his book Chiikishugi, Atarashii shicho eno riron to jissen no kokoromi (Attempts in theory and practice for regionalism and new tides of thought), Shigemura Tsutomu, representing Atelier Zo, contributed an article titled “Yanbaru no chiiki-keikaku” (Regional plan for Yanbaru). Both “Reverse Disparity Theory”[6] and “latent resources”[7] view Okinawa from an external perspective. Atelier Zo likely incorporated the ideology of regionalism into Nago City Hall.

Oshiro Tatsuhiro, a writer from Okinawa who recognized the perspective of “regionalism,” had doubts about whether Okinawa, with its potential, would be able to act autonomously as a prefecture. He foresaw that the key for Okinawan regionalism would lie in its ability to control individualistic desires (such as profit-seeking) within the region.

Energy Issues Faced by Okinawa

“In City Hall, the only sources of heat were lighting fixtures and people. Even telephone devices didn’t require AC power.” This quote comes from a lecture given in Okinawa by Shigemura Tsutomu, a founding member of Atelier Zo. There may be no other public buildings in the subtropical region of Okinawa that have managed to minimize heat load to such an extent and pursue comfort through various passive designs, with “paths for the breeze” being the forefront. However, I have not had the opportunity to experience it myself. Mechanical air conditioning was introduced in Nago City Hall using the air conditioning equipment introduced during the Kyushu-Okinawa Summit in 2000, and the ends of the “paths for the breeze” were closed off.

At the Glasgow Climate Pact during COP26 (2021), a phased reduction of coal-fired power generation was agreed upon. However, as of March 2023, ahead of the G7 Ministers’ Meeting on Climate, Energy, and Environment scheduled for April, the draft joint statement from the host country, Japan, has faced backlash from six other countries for not specifying a deadline for the phased abolition of coal-fired power plants. The government announced in 2020 that adjustments were being made to suspend or retire 100 coal-fired power plants nationwide by 2030 out of a total of 114, but there have been no further updates. In Okinawa, coal accounts for 60% of the power generation mix (2020, Okinawa Electric Power Co. Inc.).

The moat is gradually being filled, but it may be just a quiet transition to liquefied natural gas-fired power plants, which would be a postponement of the problem. While nuclear power generation receives attention nationwide, Okinawa encompasses the issue of coal-fired power generation.

Regionalism and the New Form of Capitalism

A movement from market fundamentalism to distributive stakeholder capitalism has begun in Europe and the United States, and in Japan, the ruling administration at the time raised its flag as a “New Form of Capitalism.” Among the challenges of the “New Form of Capitalism,” it seems that the construction of Uzawa Hirofumi’s “Social Common Capital” is included. During the tumultuous period before and after the reversion to mainland control, Atelier Zo, which was involved with Okinawa, used methods such as the “heuristic method” in Nago City Hall. They reconfigured the utilization of spatial elements inherent to communities (such as ashagi and amahaji) found in Okinawan settlements and homes, incorporating the ideology of “regionalism” into the functionality of architecture through the use of new material combinations.

Currently, I believe that “regionalism” and the “New Form of Capitalism” are converging with the environment and resources as keywords. The Nago City Hall, even after 40 years since its completion, continues to represent a future that we cannot catch up with.

Translated from “Okinawa kenchiku no hanseiki: Nagoshi Chosha—Zo sekkei shudan wa donoyouni Okinawa to mukiattaka (Half a Century of Okinawan Architecture: Nago City Hall—How Did Atelier Zo Engage with Okinawa?),” Kenchiku Journal May 2023, No. 1342, pp.16–17 (Courtesy of Joint Enterprise Cooperatives Kenchiku Journal)

Keywords

- Kamachi Fumiko

- Representative, ConTon Architects

- Nago City Hall

- Okinawa

- Ashagi Terrace

- shisa statues

- pillars

- Nago Bay Coastal Basic Plan

- amahaji eaves

- Atelier Zo + Atelier Mobile

- Yoshizaka Takamasa

- Iuke-logy

- stone

- reinforced concrete

- plants

- autonomy

- regionalism

- reversion

- Tamanoi Yoshiro

- Shigemura Tsutomu

- Oshiro Tatsuhiro

- air conditioning

- “paths for the breeze”

- energy

- Kyushu-Okinawa Summit

- New Form of Capitalism