See a Historic Exhibition that Will Rewrite the History of Oriental Art

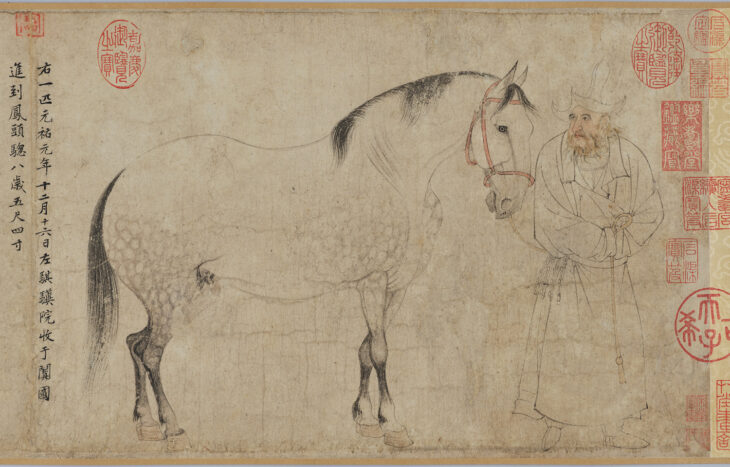

Five Horses (detail) by Li Gonglin

China Northern Song Dynasty, 11th century (Important Art Object), owned by the Tokyo National Museum

Source: ColBase (https://colbase.nich.go.jp/)

Hashimoto Mari, Director of Kankitsuzan Art Museum establishment preparation office, Odawara Art Foundation

“I will never be able to see an exhibition like this again in my lifetime.” “Researchers and collectors gather from all over the world.” This is not the Vermeer Exhibition at the Rijksmuseum [February to June 2023] we’re talking about. These comments were made in anticipation of the special exhibition “Masterpieces of Northern Song Paintings and Calligraphy,” which will be held at the Nezu Museum in Tokyo for just four weeks from November 3rd to December 3rd, 2023.

The Japanese art boom that began with Tsuji Nobuo’s (Japanese art historian, professor emeritus, University of Tokyo) Kiso no keifu (1970, Lineage of Eccentrics [2012, translated]) began in the 2000s, and interest in Buddhist statues, Jomon period artefacts and superb craftsmanship in many fields continues to this day. However, the boom has not yet reached its roots in Chinese art. Nevertheless, there are probably people who say, “Actually, I’m curious,” or people who visit exhibitions of contemporary or Western art and then one day think about Japanese and Chinese art as well. It’s better to take in as much as you can and not say it is too early to appreciate any form of art. The quotes at the beginning are no exaggeration. The upcoming exhibition is extremely important for understanding paintings and calligraphy in East Asia, including China and Japan. If you wanted to see each work separately at a later date, it would take decades.

Perhaps due to the influence of the Ito Jakuchu boom [2000s], many people nowadays associate Japanese art, especially painting, with highly colorful pictures. Before this familiarity with Ito Jakuchu, however, most people probably first thought of “light brown silk that looked as if it had been boiled” or “monochrome ink on paper” hanging in an alcove. The origins of such scroll-style works depicting mountains and water (landscapes) in black ink are to be found in Chinese paintings, specifically in the art of the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) when the form became established.

Until the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the mainstream painting method was to use brush strokes to outline the object and then add color. Paper and cloth were used as painting media, but the focus of production was on the walls of temples and palaces. However, in the 8th century, the hatsu-boku (splash-ink) technique was born, a painting method not unlike the “action painting” of the 20th century. This was a technique called “drawing mountains, stones, and other objects according to the visual associations that come from the shapes that can be created by pouring and sprinkling ink appropriately” (source of the original Japanese text: Heibonsha web version “World Encyclopedia”). However, the technique itself did not take root. Thereafter, the nature of painting changed greatly, moving from polychrome to monochrome, from figure paintings to shan shui paintings (Chinese-style landscape paintings), bird-and-flower paintings, and from wall paintings to movable hanging scrolls.

Meanwhile, the painters may be divided into two groups. One is the literati of the Song Dynasty (960–1279), those who became bureaucrats through the Imperial Examination, regardless of their family background, and who came into direct contact with the emperor, or a reserve group of them (later their scope expanded and changed). They were highly praised for the elegant spirit of their poems, paintings and calligraphy, which they wrote to relieve their boredom while doing their everyday government work. After the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), “the history of painting of/by/for the literati” became the standard. On the other hand, there were professional painters who served the imperial painting academy. Although they had mastered very advanced techniques, they were thought to be inferior to the literati in terms of the spirit of their output.

From the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–60) to the early Northern Song Dynasty, landscape painting as a form became established with the paintings regarded as art that depicted space itself. This led to the thorough pursuit of themes and techniques in which the logic of three-dimensional space was expressed on a two-dimensional plane, similar to the Renaissance in the West, taking into account the size of motifs and the intensity of light and shade. Culturally, art entered a period of maturity, such as seen in the calligraphy of Su Shi (1036–1101) and Huang Tingjian (1045–1105), who established the semi-cursive or cursive style, which emphasizes improvisational expression drawing on one’s heart. It can be said that the history of Chinese art since then has always been based on an awareness of and reference to the Northern Song Dynasty.

Although there are shades of gray in different periods, Japanese art has been enormously influenced by Chinese art throughout history. Of course, the cultural assets of the Northern Song period are no exception. However, despite the importance of Northern Song in Chinese art history, large-scale Northern Song art exhibitions have never been held at national museums such as the Tokyo National Museum or the Kyoto National Museum. The reason is simple: there aren’t many representative artworks in their collections. Northern Song paintings and calligraphy have always held a special position in China, and not many works from the period have left the country. This is less true for the paintings and calligraphy of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), the art of which period was especially loved in Japan. Although there are a few works from the Northern Song period that have been handed down in Japan, they are not sufficient to fill a large museum venue. Meanwhile, the hurdles are too high for borrowing representative works from overseas.

Thus, despite the works’ importance, there had been no “Northern Song Art” exhibitions until, at the end of 2018, a certain work was quietly added to the list of exhibits to be shown at the Special Exhibition “Unrivaled Calligraphy: Yan Zhenqing and His Legacy,” held in early 2019 at the Tokyo National Museum, Five Horses.

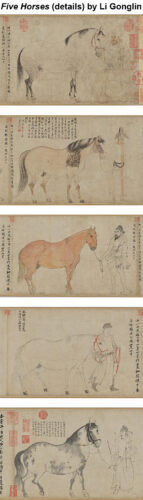

Five horses depicted on a scroll, from right to left (here from top)

Owned by the Tokyo National Museum

Source: ColBase (https://colbase.nich.go.jp/)

Five Horses, Attributed to Li Gonglin, Northern Song dynasty, 11th century (owned by the Tokyo National Museum)

News that Five Horses would be exhibited spread quickly among people all over the world who love, study, buy and sell Oriental art, and a silent roar shook cyber space. The Five Horses scroll painting was taken out of the deep courts by the Japanese during the turmoil of the Qing dynasty (1616–1912) collapse, but in 1928, it disappeared after being shown at an exhibition to commemorate the coronation of the Showa Emperor held at the Tokyo Imperial Museum (present Tokyo National Museum) and the Tokyo Prefectural Art Museum (present Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum). It was thought the work had been destroyed by fire during the Pacific War. The work’s appearance in the 2019 exhibition was the first time in 90 years that the existence of the “divine work,” for which monochrome collotype reproductions have been required to be included in Chinese art history textbooks, became clear for all to see.

In 2019, I wrote an article for Geijutsu Shincho titled “The scroll painting of five horses by Li Gonglin rewrites the history of painting in Japan and China.” In the article, I introduced the following comment from Itakura Masaaki (a specialist in the history of East Asian painting, Professor at the University of Tokyo, Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia), who was instrumental in the “rediscovery” of Five Horses. “Before the reappearance of Five Horses, the closest thing to Li Gonglin’s original work was The Classic of Filial Piety in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is clearly different from The Classic of Filial Piety as we know it, in other words, it greatly rewrites the understanding of Li Gonglin and the history of Northern Song painting, which has been established based on The Classic of Filial Piety. When I first saw the picture scroll from the beginning to the end, the question swirling in my head was, ‘What should I do about the historical position?’” (Geijutsu Shincho, August 2019, Shinchosha).

Four years later, this exhibition, supervised by Professor Itakura, confirms Five Horses’ historical position with its re-emergence. At the same time, this is an exhibition that brings together the paintings and calligraphy from the Northern Song period scattered throughout Japan.

Above all, the works to be exhibited that excited Chinese art fans, collectors, and researchers around the world the most were Li Gonglin’s Five Horses (Northern Song period, collection of Tokyo National Museum) and The Classic of Filial Piety (around 1085, Northern Song period, collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art), which will be exhibited at the same time. This is an exhibition that may never happen again. Furthermore, masterpieces from the Higashiyama Treasure—a large collection of karamono (Chinese items), including paintings and calligraphy, books, and crafts from the Song Dynasty (960–1279), which the Ashikaga shogunate collected in the Middle Ages and which came to be called by that name in later generations—will be exhibited. Among them will be Huizong’s Pigeon on a Peach Branch (1107, Northern Song period, private collection, National Treasure, exhibited only for 3 days during the exhibition period [dates to be determined]). This collection can also be seen as evidence of the Japanese authorities’ admiration of Emperor Huizong (1082–1135), the eighth Emperor of the Song Dynasty (second to last of the Northern Song Dynasty), who built a magnificent collection of cultural assets as an expression of royal power that transcended artistic taste.

On the other hand, Wintry Groves and Layered Banks by Dong Yuan (?–962) (Five Dynasties period (907–960), collection of Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures, Important Cultural Property), Pavilions Among Mountains and Rivers by Yan Wengui (967–1044) (Northern Song period, collection of Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts) and other masterpieces of landscape paintings from the Northern Song Dynasty were collected in modern times by collectors based in Kansai, Japan. I mentioned above that very few Northern Song period cultural assets such as paintings and calligraphy ever reached pre-modern Japan. However, at the end of the Qing Dynasty, all at once what had been kept in China flowed out. Apart from one work that was moved to Taipei (later stored in the National Palace Museum) by Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang, a considerable number of important works, including Five Horses, were shipped to Japan. This was partly due to Japan’s geographical proximity, but it was also due to the country’s outstanding understanding and respect for Song Dynasty art. As a matter of fact, works that have been brought to Japan since the modern era account for a large proportion of this exhibition.

Also on display will be Buddhist paintings, sutras, and bokuseki (the Chinese style of calligraphy brought by Zen priests from China) from the Northern Song period, including Peacock Myo’o (Mayura Vidyaraja) (Northern Song period, collection of Ninna-ji Temple, Kyoto, National Treasure, exhibiting only from November 21st (Tuesday) to December 3rd (Sunday), 2023), Certificate of proficiency in priesthood by Yuangwu Keqin (1063–1135) (1124, Northern Song Dynasty, Tokyo National Museum, National Treasure), which were brought from the Buddhist world that spread to the “outside lands” of the Emperor’s governing system (Sinocentrism). In addition, three calligraphy pieces by Huang Tingjian, who wrote the inscriptions on Five Horses, will be exhibited to highlight Li Gonglin’s reputation within the literati network.

It is interesting that a considerable number of kohitsugire (pieces of excellent classical calligraphy) from the Heian period (794–1185), which at first glance seem unrelated to Northern Song, are to be exhibited. They include masterpieces such as Kokin Wakashu-jo (Kansubon) (Preface to the Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times, book in scroll style) (11th–12th century, owned by Okura Shukokan, National Treasure), which can be said to be representative of the “Japanese-style” rather than Chinese, but the purpose of exhibition here is the “paper” rather than the calligraphy (which is also important). The paper used for Kansubon Kokin Wakashu-jo is a type of “wax paper” (decorated [stationery] paper) (Northern Song period) unique to China, in which auspicious omen motifs and other motifs are printed from a woodblock onto paper made from bamboo, and then a model pattern is added with kirazuri (a printing technique to scatter minute mica powder on a sheet of paper). This type of decorative paper made in China is called karakami, and later many Japanese karakami were made using the same technique in Japan.

In 2018, “A Special Exhibition of Painting and Calligraphy on Song Dynasty Decorated Paper” was held at the Taipei National Palace Museum, with the theme of writing paper in painting and calligraphy. Since then, it has become clear that karakami from the Northern Song period, decorated with patterns of flowers, birds and figures remain not only as relics from Heian-period Japan, but also in China. It is hoped that the similarities and differences that emerge from the comparison between the writing papers used by the literati in China and the papers used by the Japanese aristocrats will bring new perspectives to the art histories of both countries.

The amount of information obtained increases exponentially by comparing multiple works in the same space, even when some are already familiar. The inclusion of Five Horses in the upcoming exhibition may allow us to see new landscapes for the work that we could not have imagined before. And such a “view” undoubtedly holds the potential to change the way we look at Japanese art, too.

NEZU MUSEUM

Special Exhibition Masterpieces of Northern Song Painting and Calligraphy

Friday, November 3 – Sunday, December 3, 2023

Closed Mondays

Hours 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. (last entry: 4:30 p.m.)

General admission (On-line timed-entry tickets) Adult 1800 yen, Student 1500 yen

6-5-1 Minamiaoyama, Minato 107-0062, Tokyo Prefecture https://www.nezu-muse.or.jp/en/

This article is a translation of a revised and adjusted version of the article “Toyo Bijutsu-shi wo Kakikaeru, Rekishi-teki Tenrankai wo miyo (See a Historic Exhibition that Will Rewrite the History of Oriental Art)” in the May issue of Subaru by the same author.

Keywords

- Hashimoto Mari

- Kankitsuzan Art Museum

- Odawara Art Foundation

- art history

- Chinese art

- Japanese art

- Li Gonglin

- Five Horses

- scroll painting

- Northern Song

- painting

- calligraphy

- Nezu Museum

- Yan Zhenqing

- Higashiyama Treasure

- karamono