“Distance with Korea” considered from the Japanese-Korean publishing situation

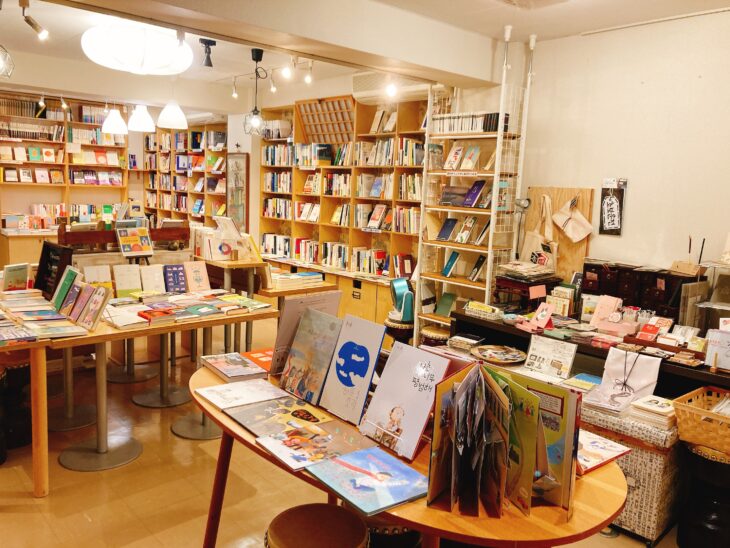

CHEKCCORI, located in Jimbocho, Tokyo’s bookstore district, is a book café run by Cuon Inc., a publishing house specializing in Korean books. In addition to about 3,500 books in Korean, including novels, poems, essays, picture books, comics, cookbooks, humanities books, and art-related books, the café also stocks about 500 Korean language study books and Korean-related books in Japanese. (As of May 2024, the café service is currently suspended.)

Photo: Courtesy of Cuon Inc. and CHEKCCORI

In recent years, there has been a growing tendency for books that are bestsellers in South Korea to become hits in Japan, and vice versa, for books that are popular in Japan to become hot topics in South Korea. A representative of a publishing company that pioneered the Korean book market in Japan talks about the current situation in Japan and Korea.

Kim Seung-bok, CEO of Cuon Inc.

Japan and South Korea have become competitive societies

——In 2019, Mr. Kim Soohyun’s essay Watashi wa Watashinomamade Ikirukotonishita (I decided to live as me [original title: 나는 나로 살기로 했다 (2016)]) (Wani Books Co., Ltd., 2019), which Ms. Kim was involved in translating and publishing, was published in Japan and became a bestseller with a cumulative circulation of 550,000 copies (1.8 million copies worldwide). Why do you think Korean “picture essays” have become such a big hit in Japan?

Kim Seung-bok: As is often said, both Japan and South Korea are highly competitive societies. Especially young people in their teens and twenties are tired of competing with others. This is probably why the book’s message of “live your life as you are without worrying about what others think” has captured the hearts of young people in Japan and South Korea.

In fact, if you look at the readership of this book, there is not much difference between Japan and Korea. The readers are mainly people in their teens and twenties. The structure of the book, with little text and lots of illustrations, is probably one of the reasons why it appealed to the younger generation. In addition, there was information on social media that Jung-kook, a member of BTS (a seven-member Korean idol group, also known as Bangtan Boys), loved reading this book, and it became a huge hit in both Japan and South Korea. It became a catalyst.

——Korean illustrator Mr. Ha Wan’s essay Ayauku Isshokenmei Ikirutokoro datta (I almost had to live hard [original title: 하마터면 열심히 살 뻔했다 (2018)]) (Diamond, Inc., 2020) also became a bestseller, selling over 300,000 copies in Korea and 150,000 copies in Japan. This book also deals with the themes of “competitive fatigue” and “self-care.”

Kim: One of the themes of the current bestselling books in both Japan and Korea is “healing.” As for books from Japanese publishers, the novel Neko wo Shoho Itashimasu (I will prescribe a cat) (by Ishida Syou, PHP Bungei Bunko) published last year (2023) became a hit in Japan with over 100,000 copies sold. The theme of this work is exactly “healing,” and there was a very fierce bidding competition among Korean publishers for the rights to publish the translation.

——Will “healing” continue to be a “popular theme” in the Japanese and Korean publishing industries?

Kim: There is definitely a demand for it. However, in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, I feel that books with different themes and messages are starting to appear in Korea.

For example, self-help books written by female opinion leaders in their fifties and sixties are selling well in South Korea. In their books, they convey the following message to the younger generation:

“The eight hours you spend at work are your life. So do your best at whatever you do.”

The essay I mentioned earlier, Ayauku Isshokenmei Ikirutokoro datta, sends the exact opposite message. It is a very interesting phenomenon that a book like this, which encourages “hard work,” is gaining support, especially among the younger generation of Koreans. Japanese publishers have already decided to publish these self-help books, and we are watching closely to see how they will be received in the Japanese market.

In any case, I think it’s true that in recent years there has been a growing tendency for books that are bestsellers in Korea to become hits in Japan, and vice versa, books that are popular in Japan to become a hot topic in Korea.

Young people in Japan and Korea

——It has been pointed out that in Japan, young people are becoming less and less interested in reading, and the number of books that can be called bestsellers is decreasing. Is there a similar trend in Korea?

Kim: The amount of money and time young people spend on books is definitely decreasing compared to other forms of entertainment such as movies and sports. However, in every era, there are always people who read books.

Korean publishers are able to throw a stronger ball to this group of people, which is probably why there have been blockbusters like Watashi wa Watashinomamade Ikirukotonishita.

——I get the impression that in South Korea there are a lot of highly designed books that young people want to pick up. Attention to the details of the book’s appearance, such as the binding and design, can be said to be one of the factors that has attracted the support of the younger generation.

Kim: It is true that Korean books have a characteristic that could be called “Korean-ness” in their bindings and designs.

For this reason, when Korean books are translated and published in Japan, it is often the case that the cover and other aspects of the book are left unchanged as much as possible. This is because young Japanese readers are increasingly buying books because they can smell the “Korean smell” in the book’s cover and are attracted to it.

——So Japanese young people are able to identify “Korean books” by their senses.

Kim: I think it’s because they are exposed to Korean information on a daily basis through social media. If they follow Korean idols and talents on X (formerly Twitter) or Instagram, they will naturally see what is trending in Korea. In other words, there are opportunities for them to see the cover of a Korean book before it is translated and published in Japan and think, “That’s a cute book.” Also, through exposure to other cultures, such as music and fashion, they may subconsciously feel something “Korean.”

——Could you say that the demographic of people who pick up Korean books in Japan has changed significantly from the past?

Kim: That’s an important point. In the past, “intellectuals” in Japan who loved books bought Korean books.

In recent years, I’ve often seen people who don’t read many books buying Korean books (translated books). Most of them are in their teens or twenties, and they like K-pop, Korean fashion, and Korean dramas.

In other words, they buy Korean books to learn about the clothes their favorite Korean celebrities wear, the novels and essays they read, and even the culture they live in.

Korean literature and the vague boundaries

——Korean literature is also beginning to be read in Japan. For example, the novel 82-nen Umare, Kimu Jiyon (Kim Jiyoung, Born in 1982 (2020) [original title: 82년생 김지영 (2016)]) (Chikumashobo Ltd., 2018) by Cho Nam-joo, which was published in South Korea in 2016, became a bestseller in Japan, selling about 300,000 copies (1.36 million copies in South Korea). Is there a “change” in the number of people reading “Korean literature”?

Kim: In the past, only a handful of Japanese people read Korean literature. In bookstores, it was often lumped together with other works such as Chinese literature in the “Asian literature” section. In recent years, however, works such as 82-nen Umare, Kimu Jiyon (Kim Jiyoung, Born in 1982) and Saishokushugisha (The Vegetarian (2016) [original title: 채식주의자 (2007)]) (by Han Kang, Cuon Inc., 2011), which you introduced, have become a hot topic in Japan, and I feel that more and more bookstores are setting up shelves dedicated to “Korean literature.”

——What are Japanese readers looking for when they read Korean novels instead of Japanese novels?

Kim: When 82-nen Umare, Kimu Jiyon became a big hit about five years ago, I think the majority of Japanese readers who read “Korean literature” did so because many of the works dealt with feminism and the difficulties of living in society. Recently, however, the stereotype of “Korean novels = feminism and the difficulties of life” is no longer true.

In fact, more and more publishers in Japan are showing interest in publishing translations of Korean science fiction and mystery novels. In addition, on the shelves of “Korean literature” in large bookstores, books are now separated by the author’s name, such as “Cho Nam-Joo” or “Han Kang.” In other words, more and more people are choosing works out of pure interest, crossing national boundaries, rather than picking up works because of “Korean literature” but because of “this theme” or “that author.”

——On the other hand, how is “Japanese literature” read in Korea?

Kim: We see similar trends. When Japanese novels came to Korea, the majority of people who read them were attracted to the genre of “Japanese literature.” I remember that the uniquely Japanese “I-novels” were especially popular.

Recently, however, an overwhelming number of readers say, “I read it because it’s Murakami Haruki” or “I pick it up because it’s Higashino Keigo.” In other words, I feel that the framework of “Japanese literature” and “Korean literature” is gradually becoming vague for readers.

——So the criteria for judging is becoming less about the country and more about the author and the theme.

Kim: That’s right. It’s pretty much the same reason why young Japanese girls become fans of BTS and NewJeans (a Korean five-piece girl group).

They didn’t fall in love with BTS because they were “Korean idols,” but because they were attracted to them as artists, and it just happened to be a Korean group.

Looking back, in the food industry, a Korean dish called “cheese dakgalbi (Korean spicy chicken stir-fry)” was popular with Japanese people for a while. For Japanese people, it’s not because they want to eat Korean food, but because it’s delicious. More specifically, there may have been a very simple reason: “It looks good on social media.” In particular, I feel that the younger generation in Japan has a rather “flat” view of Korean culture.

——How do young Koreans view Japanese culture?

Kim: It’s the same with young people in Japan. I feel that there are many people who come into contact with Japanese culture without prejudice, saying “I like what I like” and “what’s cool is cool.”

On the other hand, Koreans in their fifties and older may have a different impression of Japan than younger people.

Simply put, there are still people who have a sense of rivalry with Japan, and they evaluate Japanese culture with a “catch-up and overtake” attitude.

However, as I mentioned earlier, young Koreans today have neither admiration nor inferiority feelings toward Japan. Like young Japanese, they have a “flat” perspective, and if they see Japanese culture that they think is “cool,” they will share it on social media, and if they think “Akihabara’s culture is interesting,” they will visit it on vacation.

——How do young Koreans view the “political problems” that exist between Japan and South Korea?

Kim: In terms of “cultural demand,” as far as I know, there doesn’t seem to be any political influence. I feel that there are more and more Koreans, especially among the younger generation, who don’t bring the statements of politicians or the atmosphere of politics into cultural exchange.

Are there any “books that can only be sold in Korea”?

——As the current young generation becomes the center of society, will there be a gradual decline in the number of books that can only be sold in Korea or, conversely, that can only be accepted in Japan?

Kim: That’s a difficult question. For example, a book that deals with Korean labor issues would be good if it sold 2,000 copies domestically. Of course, the chances of it becoming a bestseller in Japan are close to zero.

Recently, however, we have been receiving offers from Japanese publishers to translate specialized books. The underlying idea seems to be that even if they don’t expect a big hit, they will publish the book because there are people who need it.

This means that even if a book deals with issues unique to Korea, there will always be readers at home and abroad who want to read it.

In addition, although the Korean conscription system does not exist in Japan at present, events and books that explain the system are now attracting interest, especially among Japanese young women. This is because they are curious about what kind of system and life their favorite K-pop idols will lead if they serve in the military.

In this sense, it is impossible to predict what will trigger a deepening interest in a country, and I feel that the number of “books that can only be sold in one country” will probably decrease.

South Korea generously supports the publishing and bookstore industry

——Are there any major differences between Japan and Korea in the publishing industry as a whole?

Kim: South Korea’s population is about 50 million, much smaller than Japan’s, and the publishing industry is in a difficult situation. However, I think the government support measures are more comprehensive than in Japan.

In fact, the reason why so many Korean books are sold in Japan is because of the strong support and policies of the Korean government. Of course, there are similar systems in other countries, but Korea has a much more generous support system.

First of all, books and magazines are tax-free in Korea. For example, in a bookstore attached to a coffee shop, sales of food and beverages are subject to tax, but sales of books and magazines are exempt from sales tax.

Second, there is a system in which the government buys 10 million won (about 7,338 USD) worth of books from publishers and supplies them to libraries. In other words, the government not only provides subsidies, but also supports the management of publishers by purchasing high-quality books. The purchased books can be sent to overseas organizations as promotional samples.

Third, South Korea also has a system of supplying books to the military. They come in a wide variety of genres, including novels, poetry collections, essays, and history books, and when they are delivered to the military, publishers receive orders for tens of thousands of copies. In fact, I heard a friend who works in a Korean publishing house say, “Business has improved because we were able to supply the military this year.”

Fourth, there are also support measures for publishers expanding overseas. For example, publishers receive subsidies for participating in book fairs in countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Taiwan, Japan, Spain, and the United States. Of course, there is an entry system, but if you are selected, you will receive a substantial grant from the government.

——Why does the Korean government support publishers and bookstores so generously?

Kim: I think it’s because we believe that “book culture must not die out.” In fact, “reading” is not as deeply rooted in society in Korea as it is in Japan. That’s probably why there’s a sense of crisis that the publishing industry will collapse if nothing is done.

South Korea also has a system that supports small town bookstores and civic book clubs. In fact, if a small bookstore holds a lecture by an author, the government will pay the author’s fee. Of course, if you apply and get approved, it’s a story. In addition, the cost of citizen book clubs can be subsidized by the government as long as the application is successful. Behind these support measures, we can see a sense of impatience that “publishers and bookstores should not be put out of business.”

——What kind of activities do you plan to do in the future, given the tough publishing environment in both Japan and South Korea?

Kim: I’m from Korea, so I can read books published in Korea faster than Japanese editors. Also, since we have a publishing company in Japan, we can get our hands on popular books in Japan faster than Korean editors.

By using this strength, we want to connect Japan and Korea and bring “good books” from Japan and Korea to more people. My happiness is to make good books known, but I’m sure that will lead to everyone’s happiness as well. Like the young people in Japan and South Korea, I would like to continue to discover “good content” from a flat perspective.

Interviewed by Abe Junpei, Editorial Department of Voice

Translated from “Tokushu 1 Kankoku no Genjitsu: Shuppanjijo kara kangaeru ‘Kankoku to no kyori’ (Special Feature 1 The reality of South Korea: “Distance with South Korea” considered from the publishing situation),” Voice, May 2024, pp. 84-91. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [June 2024]

Keywords

- Kim Seung-bok

- Cuon Inc.

- CHEKCCORI

- Korean literature

- Japanese literature

- publishing industry

- bookstores

- novels

- picture essays

- self-help books

- healing

- competitive fatigue

- self-care

- self-help

- Kim Soohyun

- Watashi wa Watashinomama Ikirukotonishita

- I Decided to Live as Me

- 나는 나로 살기로 했다

- Jung-kook

- BTS

- Ha Wan

- Ayauku Isshokenmei Ikirutokoro datta

- I almost had to live hard

- 하마터면 열심히 살 뻔했다

- Ishida Syou

- Neko wo Shoho Itashimasu

- I will prescribe a cat

- Korean idols

- social media

- Cho Nam-joo

- 82-nen Umare, Kimu Jiyon

- Kim Jiyoung, Born in 1982

- 82년생 김지영

- Han Kang

- Saishokushugisha

- The Vegetarian

- 채식주의자

KIM Seung-bok

KIM Seung-bok