Amazed by Fujiwara no Teika’s handwriting—A gift that has lasted 800 years

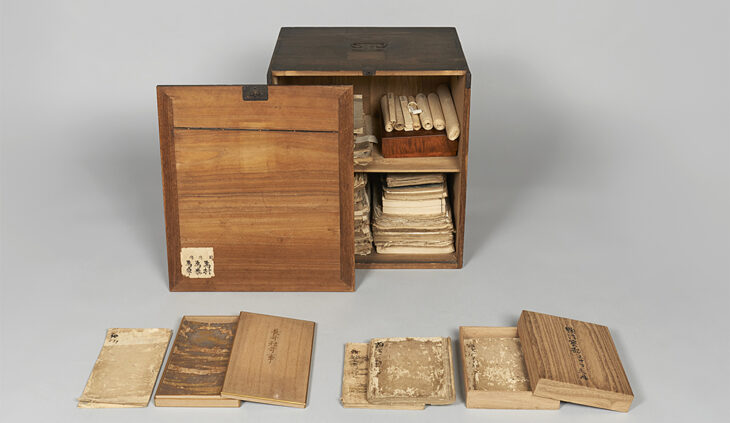

The box of “Kokin denju” for the succession of a secret poetic interpretation of the Kokin Wakashu where Kenchu Mikkan was found

Photo: Courtesy of Reizei Family Shiguretei Bunko Foundation

The existence of the box, which had been handed down in the Reizei family, was known.

It had never been opened since 1896 and had been passed down quietly in the family—I had just kept it out of respect without opening it.

In 1980, an investigation of the entire Reizei family book collection began, and as the collection was examined step by step, in 2022 the box was opened for the first time in almost 130 years. Many valuable documents had already been found in earlier research work, and I thought that there would be nothing of great value in the box. Therefore, I was surprised when the team of scholars in charge of the investigation told me that a commentary on the Kokin Waka Shu, the Kenchu Mikkan, handwritten by Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241) had been found. The professors who discovered it were still excited and said, “We never thought that something at the level of a national treasure would still be lying dormant.”

These are the words of Reizei Tamehito, the 25th head of the Reizei family, as he speaks about this discovery of national treasure level. The Reizei family has an 800-year history, with Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114–1204), who was regarded as a kasei (great poet), and his son Teika as distant ancestors. Known as a family that has taught waka (31-syllable poems) at the Imperial Court for generations, the Reizei family storehouse, which has protected many valuable documents, is known as the Shosoin [Repository] of Documents. Reizei Tamehito also serves as the president of the Reizei Family Shiguretei Bunko Foundation (Kyoto City), which preserves and passes on the documents. (This article is a compilation of comments made by Reizei Tamehito to the editorial staff of Bungeishunju.)

The box that contained the Kenchu Mikkan was about 35 cm long, 50 cm wide, and 55 cm high. It was not a high quality painted box, but a worn wooden box.

Kenchu Mikkan is a commentary on the first Japanese imperial anthology of waka poetry, Kokin Waka Shu (collection of ancient and modern poetry, usually abbreviated to Kokinshu)[1], in which Teika added his own commentary to that of the monk and poet Kensho (1130?–1209?). Kenchu Mikkan is an essential book not only for waka studies but also for Japanese literary studies, and although several copies survive, the original was thought to be lost.

A box that was opened only once when the head of the Reizei family took over

In fact, there was a time when this box was opened regularly. Whenever a new head of the Reizei family took over, the successor would open it once, carefully read the books inside, and inherit the kagaku (poetics) that had been passed down in the Reizei family.

In particular, the succession of the interpretation of Kokinshu is called “Kokin denju” (initiation into the Kokinshu) and since it took the form of isshi soden (sole succession) and was orally transmitted from father to only one son, it was considered very auspicious to open the box only once at the time of succession. After the denju initiation, a grand poetry party was held and a goei (portrait) called “juzo” was painted in commemoration. The head of the family who received the denju kept a box of “study notebooks” in which he wrote down the results of his new studies and passed them on to future generations.

For this reason, great care should be taken in opening this box. The starting date was October 3, 2022. A priest of ujigami-sama (the god of the family lineage, Goryo-jinja Shrine in Kyoto) was invited to perform a ritual and asked the waka gods and ancestors for permission to open the box.

When the Reizei family accomplishes something important, they perform a ritual called “kami-oroshi” and “kami-age” (before a festival, they welcome the spirits from heaven to the shrine and then return them to heaven after the festival). This time, the investigators rinsed their mouths and washed their hands before touching the boxes and books.

When they opened the box, they found a considerable number of documents and classics, including 60 booklets and 58 old documents. In addition to the documents mentioned above, the box also contained the study notes of past family heads, which were filled with small characters written between the lines.

It took time to carefully examine each item, but after listening to the opinions of many experts and undergoing thorough academic verification, we announced in April 2024 that the Kenchu Mikkan handwritten by Fujiwara no Teika had been discovered.

“Thanks to Teika…”

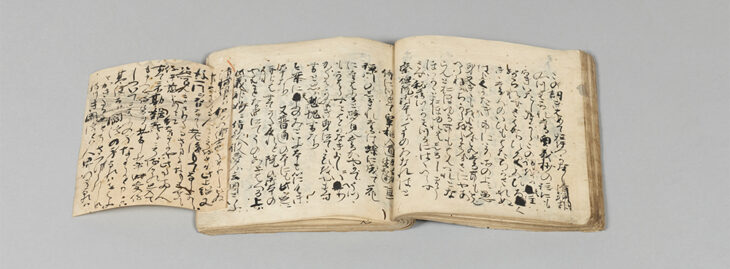

This research confirmed that the second and third volumes of the three volumes in the box were written in Teika’s own handwriting. The paper used dates from the late Heian period (794–1185) to the early Kamakura period (1185–1333), when Teika lived, and at the end of the third volume, Teika’s pseudonym (Hachiza Chinro) is inscribed in his own distinctive handwriting, proving that it is undoubtedly the original copy in his own handwriting. The marks and revisions not preserved in the manuscript provide valuable clues for studying Teika’s thinking.

By the way, the writing style, called “Teika-yo” (the Teika style), is unique and is still popular today. It is believed that Teika developed this style because he needed to write quickly and accurately in order to produce many copies. By writing rhythmically and quickly, the opening stroke [starting at a 45-degree angle (the angle at which the brush touches the paper), then re-striking (applying strong pressure once and releasing it slightly before moving on to the next stroke)] is naturally eliminated, the continuous kana character is reduced, and the thickness of the lines is varied.

Professor Katagiri Yoichi of Kantai University once told me this with deep emotion.

“Thanks to Teika’s existence and his active copying of classical documents, modern Japanese classical literature was established.”

Those words are still etched in my mind.

The books that Teika copied are the source books of today, including not only Kokinshu, but also Sarashina Nikki[2], Ise Monogatari (Tale of Ise)[3], Genji Monogatari (Tale of Genji)[4], Gosen Waka Shu[5], Shui Waka Shu[6], and so on. On the other hand, if he had not been so diligent in copying, these works might never have come down to us.

As far as we know, Teika copied the Kokinshu 16 times. Kenchu Mikkan contains interpretations written between the lines, additions made by pasting papers, corrections made by rubbing out, and kanmotsu (notes on letters, phrases, and sentences in a text compared to the original). These are vivid traces of Teika’s deepening thoughts on the Kokinshu. This discovery will allow us to come closer to understanding how Teika interpreted the Kokinshu and how he intended to carry on the tradition of the songs.

Kenchu Mikkan (medium volume) with colored paper on which Fujiwara Teika wrote and attached his own interpretation

Photo: Courtesy of Reizei Family Shiguretei Bunko Foundation

“Please compose a reply poem.”

I was not originally a member of the Reizei family. When I was 40 years old, I married my wife Kimiko and became a son-in-law in the Reizei family.

Until then, I had studied art history at the university, so I thought I understood that the Reizei family was the master family of waka and what kind of family it was. But when I actually entered the family, I realized that it was a terribly difficult place. Moreover, since I married into the family, I have to carry on the Reizei family line. Because of this pressure, I sometimes secretly asked myself, “Why did I join as mukoyoshi[7] (adopted son-in law)?”

The Reizei family has not only tangible cultural assets, such as classics like the Kenchu Mikkan, but also many intangible cultural assets, such as poetry parties and annual events. I will never forget the day of our first setsubun (bean-throwing ceremony) after our marriage. It must have been about three months since I joined the Reizei family. After we finished throwing beans in over 30 places in the huge residence, including the rooms in the main house, the kitchen, the entrance, and the outbuildings in the front and back, we all sat down to eat.

After a while, Tameto, the former head of the family and my father-in-law, suddenly stood up from his seat. I continued to eat, watching his back as he went into his study, and when he returned, he handed me a piece of paper. Before I could ask him anything, he said, “Please compose a poem in response to this poem of mine.” I quickly looked down and saw a poem written by my father-in-law on the paper: “Toshikoshi no / oniyarai suru / onoko woba / wagaya ni mukaeshi / kyo no yorokobi (Today I am so happy to welcome home a boy who will perform the New Year’s oni-yarahi (throwing beans to drive away demons).”

It was so sudden that I couldn’t answer right away and fell silent. After a while, all I could do was tilt the sake bottle in front of me and offer it to him, saying, “Here you go.” There was no way I could compose a poem.

I still vividly remember the look on the former head’s face when he received it, grinning and drinking without saying a word. Looking back, I think the first thing he wanted to tell me was that the Reizei family is a “house of waka.”

The waka in “kaeshi” (reply) comes from a poem I wrote in 2002, the year I became the Foundation’s third president: “Yaotose no / totsu miya no / fumigura wo / chiyo ni yachiyo ni / nao tsutaenan (May the library of our distant ancestors of eight hundred years be passed on for a thousand and eight thousand generations.)” It’s been 22 years already. This year marks my 40th year in the Reizei family.

“As the head of the Reizei family, what should I do first?” If asked now, I would say, “Get used to it.” Many traditional Japanese arts have a kata (style). It is said that Genji Monogatari follows Ise Monogatari, and there is a “kata” in it as well. In archaic Japanese, the word “manabu” (to learn) is pronounced “manebu” (to imitate), and it has long been said that “art begins with imitation.”

Especially for intangible cultural assets such as the Reizei family’s poetry parties and annual events, it is difficult for each person who inherits their content to have a correct and common understanding, and there is a risk that the original spirit contained in them will be lost over time and transformed into something else without being noticed. In this situation, “kata” that embodies strict norms and etiquette is indispensable. The head of the Reizei family has cherished Kokinshu for generations and has learned it as the “kata” of the ideal waka because he has felt the importance of “kata” in the tradition more deeply than anyone else.

I myself feel that I have been working hard to get used to these “kata” for the 40 years since I joined the Reizei family. Even if it is difficult to understand at first, you will naturally pick it up as you repeat it. I believe that passing on the “kata” that has been mastered in this way to the next generation is what will ensure the survival of tradition.

Shunzei’s handwriting made me shiver

However, the decision to take over a family that had been in existence for about 800 years was not an easy one. I will never forget the day I finally made up my mind.

It was around the time that the preparations for the major repair of the Reizei Family Residence began, so it must have been 1993. I had the opportunity to study Korai Futeisho (Notes on Poetic Style through the Ages), handwritten by Shunzei, the father of Fujiwara no Teika.

Korai Futeisho is a karonsho (study of poetics) in which Shunzei selected excellent poems from the Imperial Anthology of Waka Poetry from Kokinshu to Senzai Waka Shu[8] in addition to Manyoshu[9], showing the style of expression and its changes. When the Reizei family announced the existence of the original handwritten copy in 1981, it caused a great stir. Until then, only copies from the Edo period (1603–1867) had been available, and suddenly an original from the early Kamakura period, handwritten by Shunzei, was discovered. I was not a member of the Reizei family at the time, but I well remember how the newspapers and television all reported the discovery as a national treasure.

Then, when I saw the thin kozogami (mulberry paper) attached to the end of the second volume, I suddenly shivered, and a shock ran through my whole body as if my hair stood on end.

“What on earth was I looking at?”

I couldn’t take my eyes off it, wondering what it was. The writing of Shunzei was so dignified and beautiful. It had a dignified power and even a certain aloofness. I felt as if Shunzei was saying to me, “Please take good care of the Reizei family and its culture that has lasted for 800 years.”

I also noticed that the Korai Futeisho had been rubbed by hand. Think of the English-Japanese dictionary you had in high school. As you use it, the edges gradually darken and curl. The same thing happened to books from 800 years ago. Even though it is a precious book that must be treated with care, the fact that it still has these marks shows how avidly the successive heads of the family read it.

Seeing Korai Futeisho with my own eyes and touching its history, I decided to become the “kuraban (library keeper) of the Reizei family” and thus the “kuraban of Japanese culture.” At that moment, I realized that this was the job that had been given to me and that only I could do it. Since I married into the family and officially became the head of the family, it was Shunzei’s calligraphy [handwritings] that helped me relieve the anxiety and pressure I felt alone, and I still feel his unfathomable power in his calligraphy.

Salary turned into tiles and walls

I was determined, but there was a wall in my way. It was a big, thick wall called money.

“My salary has turned into roof tiles and walls.” When my father-in-law, Tameto, who was the head of the family and also worked for a cooperative, was drunk, he would complain that more than half of the money he earned disappeared in repairs to the Reizei family residence.

The Reizei Family Residence, located across from the Kyoto Imperial Palace, was rebuilt after being burned down in the great fire of the Tenmei period in 1788 and has been protected for about 235 years. It is the only surviving aristocratic residence in Japan and has been designated an Important Cultural Property by the government. However, this means that the owner must protect and pass it on. The Reizei Family Residence constantly finds places that need repair, so it requires a lot of money to repair.

In addition, the Reizei family has five national treasures, 48 important cultural properties, and well over a thousand classic books designated as national cultural assets. It costs a lot of money not only to maintain these resources, but also to pass them on to the next generation.

Major repairs costing one billion yen

My predecessor established the Reizei Family Shiguretei Bunko Foundation in 1981 to contribute to these expenses and to preserve and pass on the tangible and intangible cultural properties of the Reizei family.

The most important wish since the foundation’s establishment has been to make major repairs to the Residence, which had been postponed until then. However, the cost of the repair, which began in 1994, totaled 780 million yen, including various expenses such as environmental improvement. At that time, repairs to volume 54 of Teika’s diary Meigetsuki[10], which had begun in 1987, were being carried out in parallel with the renovation of the Residence, at an estimated cost of 220 million yen. Combined with the major renovation of the Reizei Family Residence, one billion yen was needed.

Frankly, I was at a loss. About half of the costs were covered by subsidies from the national government, Kyoto Prefecture, and Kyoto City, but the other half could not be covered even with the Foundation’s budget. Protecting a national treasure by one family alone is more difficult than I imagined.

So I thought about doing exhibitions. When I was studying art history, I often helped with exhibitions, so it was an opportunity to use my knowledge.

At that time, it was not easy to pronounce the family name “Reizei” correctly. By exhibiting the treasures of the Reizei family in Japan and abroad, I wanted everyone to know about the Reizei family first. With this thought in mind and with the help of my friends, I opened “Miyabi: Japanese Court Culture” at the Guimet Museum in Paris in 1993.

The exhibition was featured in local newspapers in Paris and was a great success. In Japan, we were able to hold two exhibitions, “The Reizei Family no Shiho-ten (The Reizei Family Treasures Exhibition)” (1997–1999) and “The Reizei Family Ten (The Reizei Family Exhibition)” (1999–2002), which attracted over 780,000 and 212,000 visitors, respectively, and sold a total of 135,000 catalogs. The profits from these exhibitions were used to cover the costs of repairs, and we were able to successfully complete the two major repairs.

“Not meant to be shown to others. …..”

Some things must be changed to preserve history and tradition.

There was a symbolic event during the aforementioned exhibition. In an exhibition called “The Heads of the Reizei Family” (the third part of The Reizei Family no Shiho-ten), goei portraits of the family heads and their wives from the Kamakura to Meiji periods were displayed. However, these were originally goshintai (sacred objects) and were only to be used during rituals performed by the Reizei family and were not to be shared with anyone outside the family. My mother-in-law was not very enthusiastic about exhibiting such important objects.

“They are the gods of the Reizei family and are not to be shown to the public.”

Considering the traditions and customs up to that point, this is exactly right. However, in order for the Reizei family to survive, the exhibition had to be a success at all costs. I kept telling her, “The exhibition will not be a success if our ancestors are not present (if they don’t approve of their portraits being displayed). Finally, my mother-in-law agreed, and we decided to display the goei of the waka god, which was also cherished as a “goshintai.”

The opening of the box, which had not been opened for about 130 years, could also be seen as a new attempt to preserve the tradition.

Recently, my feet have been hurting and I can no longer sit upright. Just when I was thinking about handing over the chairmanship to a younger person, Teika sent me Kenchu Mikkan after 800 years. We have only examined about a quarter of the library’s collection. There are probably many more valuable books lying dormant. As the kuraban (library keeper) of the Reizei family, I believe that I must continue to look to the future of this family and protect and pass on Japanese traditions.

Translated from “Kokuho Machigainashi no Daihakken: Jikihitsu no Fujiwara no Teika ni Gyotensita—Happyakunen no tokiwo koete todoita okurimono (A Major Discovery That Is Sure to Be a National Treasure: Amazed by Fujiwara no Teika’s Handwriting—A gift that has lasted 800 years),” Bungeishunju, July 2024, pp. 212–219. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [August 2024].

[1] The Imperial Anthology of Waka Poetry, completed in 905, consists of 20 volumes and contains about 1,100 poems. The collection of imperial anthologies of waka poetry from Kokin Waka Shu to the eighth, Shin Kokin Waka Shu (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poetry), is specifically referred to as Hachidai Shu (Eight Great Anthologies of Waka Poetry).

[2] A memoir written by Sugawara no Takasue no musume [a daughter of Sugawara no Takasue] about the first half of her life from the age of 13 to 51, written around 1060.

[3] A biography of a person believed to be the poet Ariwara no Narihira (825–880). Produced in the early Heian period, it is the oldest uta-monogatari (poem-tale). The author and year of its publication are unknown.

[4] A long story written by Murasaki Shikibu (973–1014 or 1025) depicting aristocratic society, composing 795 waka poems. It consists of 54 chapters, and the date of its publication is unknown, but it first appeared in literature in 1008.

[5] The second Imperial anthology of waka poetry after Kokin Waka Shu [the second of the Hachidai shu]. In 951, it was compiled by order of Emperor Murakami, and contains 1,426 poems. It is thought to have been compiled around 956.

[6] The third Imperial anthology of waka poetry after Kokin Waka Shu and Gosen Waka Shu. The author is unknown, but it is said to have been compiled around 1005–07.

[7] Mukoyoshi, son-in-law adoption, is a unique Japanese concept of family, lineage, and genealogy, and is a marriage method to ensure that a family line does not die out. The son-in-law is adopted by the wife’s parents, marries the wife, and takes the wife’s surname. This allows the son-in-law to inherit the wife’s family, land, and family business (the assets that make them up).

[8] It was compiled by Fujiwara no Shunzei, but it is said that Fujiwara no Teika also assisted in the compilation. This is an imperial anthology of waka poetry published in 1188. It contains 1,288 poems in 20 volumes.

[9] Published at the end of the Nara period (710–794), this is the oldest collection of waka poetry in Japan, containing some 4,500 poems in 20 volumes by a wide range of poets, from emperors to farmers.

[10] It is a collection of Teika’s diaries, covering a period of 56 years from 1180 to 1235, of which many fragments have been handed down, as well as the original handwritten version.

Keywords

- Reizei Tamehito

- Reizei family

- Reizei Family Residence

- Reizei Family Shiguretei Bunko Foundation

- Fujiwara no Teika

- Fujiwara no Shunzei

- poetry

- waka

- Kokin Waka Shu

- Kokinshu

- Kenchu Mikkan

- Kokin denju

- handwriting

- Teika-yo

- Teika style

- kata

- style

- copying

- Sarashina Nikki

- Ise Monogatari

- Genji Monogatari

- Gosen Waka Shu

- Shui Waka Shu

- mukoyoshi

- adopted son-in law

- manabu

- manebu

- imitation

- art

- Japanese literature

- exhibitions

- goei portraits

- goshintai sacred objects

REIZEI Tamehito

REIZEI Tamehito