Dialogue: Will the Day Come When China and India Coexist as Major Powers?

|

|

| Horimoto Takenori, Visiting Professor, Gifu Women’s University of Japan | Kawashima Shin, Professor, University of Tokyo |

Kawashima Shin: China is making a range of moves, both large and small, with the National Congress of the Communist Party of China imminent this fall. But we need to keep our eyes on India, in addition to observing how China will change in units of 10 years and 20 years when we think about the future of the world and the future of Asia.

Horimoto Takenori: China and India combined are said to have accounted for half of the global GDP in the middle of the 18th century. The same situation is likely to emerge in the second half of the 21st century. To begin with, only two countries in the world, China and India, have populations exceeding 1 billion at the present time. The framework of the world order may change significantly when China and India combined account for half of the global GDP once again. David Shambaugh, a China specialist in the United States, concluded China Goes Global, his recent book, by stating, “China’s opening to the world in 1978, the world has changed China—and now China is beginning to change the World.” In other words, China is transforming itself into a game changer. The question is whether India can actually do the same thing. I think that India has the potential to achieve such self-transformation.

Kawashima: I think so, too. The armed forces of both countries are continuing their standoff in Bhutan at this very moment. (The armed forces of China and India agreed to their “prompt evacuation” on August 28, 2017.)

Horimoto: China began constructing a road on Doklam plateau, which is a disputed territory on its border with Bhutan. India objected to this action and sent its armed forces to the plateau. That was in mid-June. The two forces have remained in a state that is one step short of an armed conflict in the area for more than two months now. Bhutan was under the protection of India until 2007, when it regained diplomatic autonomy at long last. India continues to pour 1 billion U.S. dollars into the national budget of Bhutan every year, though. A country with no diplomatic relationship with China, Bhutan wants to shake off the yoke of India. However, India stops resources and food from entering Bhutan by blocking the land routes when the country shows any attempt to approach China. The ongoing standoff began under these circumstances. According to one view, the road China is building will be able to bear the load of vehicles weighing 40 tons each. In other words, the road is said to be solid enough for tanks to pass.

Kawashima: A railroad line to Lhasa in Tibet that opened in 2006 will be extended this year. Its eventual extension to Nepal is in sight already. Roads are being built one after another. From an Indian point of view, China must look like it is inching toward South Asia. It may be difficult to tell India not to exercise caution.

Horimoto: To begin with, India has distrusted China for many years. But strangely, China has had no such distrust of India.

Kawashima: China has practically no sense that it fought a war with India (known as the Sino-Indian War). On the other hand, India is planning to carry out joint military exercises with Russia in October 2017. A press secretary for the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced expressly that the exercises are regular ones that should not be linked with Sino-Indian relations. They are enough to irritate China, however.

China is Beginning to Feel Impatient

Horimoto: India has viewed itself as a major power for many years. But no other country has accepted this view. This view is now finally becoming a reality. The United States is still a major power, but China is rapidly closing in on it. India is following China one or two laps behind. I think that is the current picture.

In my opinion, major powers have both of the following two factors. The first factor is the possession of the self-capacity to cope with the influence exercised by other countries. The second factor is the ownership of the capacity to exercise an influence on other countries. China is beginning to have both of these capacities, but India has only the former. In short, India lacks the capacity to construct a world order.

Kawashima: But India has the willingness to perform the task. India’s transformation into a major power is easy to understand when you look at its increasing economic and military might.

Horimoto: Looking at the economy, India ranks seventh in the world in terms of GDP in 2016. Its economic growth rate is around 7%. The rate for India has started to surpass that for China. According to data released by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute last year, India ranks fifth in the world after the United States, China, Russia and Saudi Arabia in terms of military expenditure. The country has overtaken Japan before we realized it. On top of this, India is a nuclear power.

What supports India’s strength is definitely its population of 1.3 billion, which is the second largest in the world after China. The key aspect of this population is its median age, which is a young 25 years. The median age in China is 35 years, and that in Japan is 45 years.

Kawashima: Population is an extremely important issue. In China, the workforce has already started to decrease. But India still has a workforce of a considerable size in reserve. The median age of 25 years of people in India means it will take several decades before the country’s population starts to age.

Displaying the level of strength it is showing now will hardly be possible for China in the 2030s and 2040s. As you are aware, Japan allocates 5 trillion yen to defense expenses and devotes 100 trillion yen to social security expenses. Though not to the extent of Japan, China is spending more than 50 trillion yen on social security. China will have to spend more money on social security in the future as the aging of its society advances. It will become increasingly difficult for China to make inroads in foreign markets because its economic growth has already reached a ceiling. For this reason, China is currently pursuing the basic policy of doing what it can before it is too late.

Horimoto: When viewing matters from the Indian side, it is easy to understand that China is beginning to grow impatient.

Kawashima: India studies how China is doing things, keeps China in check from the outside from time to time, and observes how things are from the inside by moving into China’s plans now and then because the country still has plenty of time. India, which is able to take these actions, looks both envious and unpleasant to China.

Horimoto: I think that India also has geopolitical advantages. India is located precisely in the middle of the Eurasian Continent. It is located away from both Europe and East Asia to a certain extent. In addition, India sticks out into the Indian Ocean. Fortunately or unfortunately, China is located on the edge of the Continent.

Kawashima: Historically speaking, India became a British colony precisely because of its location in the middle of the East and the West. China was able to escape full colonization because it was located in the Far East. However, India obtained the weapon called English in exchange for colonization. This can be seen as an overwhelming advantage today. In addition, there is a troublesome country called Japan located very close to China. This country has been an obstacle to China’s global and regional plans. What Japan means to China is different from what Pakistan means to India.

But neighboring countries, such as Sri Lanka and Nepal, must think about how to keep India in check while sensing its power, because it is a huge nation. Tense relations between India and its neighbors produce openings for China to step in.

Horimoto: Neighboring countries can never match India one on one. For this reason, they always play the China card.

To begin with, countries like Japan and the United States expect India to play the role of a checker of China. India understands this expectation very well.

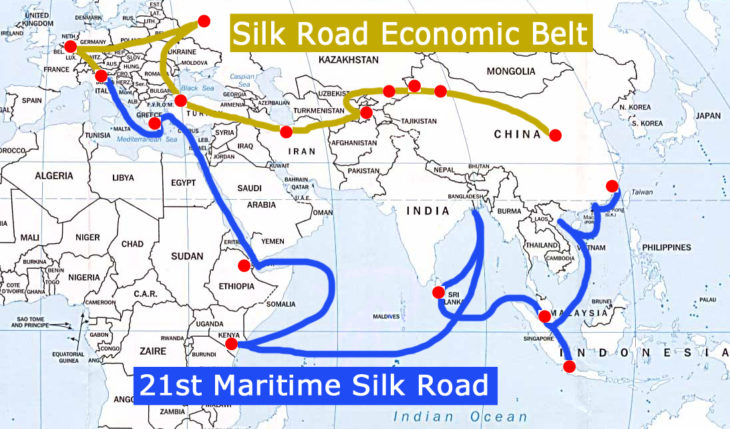

Kawashima: Under the Barack Obama administration, the United States attempted to build a huge tetragon in an area stretching from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean by taking Australia and India into its group. Xi Jinping found this attempt extremely unpleasant because it was aimed at placing a cordon right around China. That is why China is approaching India’s neighbors wanting to use the China card and building roads and ports for them. By doing so, China is keeping the cordon in check in return. The One Belt and One Road (OBOR) Initiative is a classic example of such activities. China is taking advantage of the axes of conflict and problems in the politics of the respective regions to increase its influence. India’s neighbors know that China is dangerous, but they feel that they must use China to counter India, which is their main enemy. I think that countries in South Asia are feeling entirely differently from those in East Asia regarding this point. I felt this strongly when I visited India and Sri Lanka in December 2016.

One Belt and One Road Initiative is Irritating India

Horimoto: The OBOR Initiative gives the impression of a great game over South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a flagship project in this game. The CPEC is a project for comprehensive development, including the establishment of special economic zones and the development of the electric power business, not limited to transportation infrastructure. The project covers an area that stretches from Kashgar in China to Gwadar facing the Arabian Sea by way of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK), which India claims to be its own territory. It is estimated that investments in the CPEC will total 63 billion U.S. dollars.

Kawashima: The OBOR Initiative is irritating India, isn’t it?

Horimoto: That’s right. India cancelled its participation in the OBOR Forum held in May 2017 at the last minute, citing the Kashmir border dispute as the reason for doing so.

China has the right to manage and operate Gwadar Port. It won’t be surprising if China transforms the port into its naval base in the future. The port may already be on its way to becoming the Chinese base. China is now building Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka in the same way. China’s military presence in the Indian Ocean will rise dramatically when it obtains bases in Gwadar and Hambantota.

| China’s One Belt and One Road Plan |

|

Kawashima: Economy and military affairs are the two wheels of the OBOR Initiative. Initially, China placed the emphasis on both land and sea. But things advanced better at sea. Under Donald Trump, the U.S. administration is reducing its commitment at sea, including the Indian Ocean. China is acting more strongly in areas such as the Indian Ocean for that reason. The situation is making things very difficult for India. The country asked Japan and the United States to have the idea that India equals the Pacific in terms of weight and to view security in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean as a set. When I visited the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, many officials told me that Japanese people view the OBOR Initiative overoptimistically.

Horimoto: In the Indian Ocean, the United States has bases in Diego Garcia and Djibouti. I think that the United States cannot allow China to do as it likes too readily because the Indian Ocean is related to the situation in the Middle East.

The OBOR Initiative is affecting politics among India’s neighbors significantly as well. For example, dissatisfaction is feared to worsen terrorism if the Pakistan route of the CPEC does not pass through the poorest area. Furthermore, China’s investments in Pakistan are said to require repayment to a considerable extent, even though the breakdown is unknown. There is a view circulating in India that Pakistan will become a province of China. As a matter of fact, in Sri Lanka, the current administration is blaming its predecessor for the conversion of the country into a Chinese province with debts in connection with the construction of Hambantota Port. From a negative perspective, this is a debt trap policy.

Kawashima: Doesn’t the Chinese way of grasping points among India’s neighbors, such as the port in Sri Lanka and the course of the CPEC, remind you of something? China took the right to operate the port for 99 years by lease and seized a dozen kilometers of land around a railway it built. Those are the things that other countries have done to China in modern history.

Horimoto: I see.

Chinese Rules and India with No Rules

Kawashima: As I said before, India did not take part in the OBOR Forum held in May 2017. But India joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) with Pakistan as its official member in the following month. India appears to be attempting to enter the inner sanctum of China while keeping the country in check.

Horimoto: India is taking part in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as well. India is doing so because it needs funds for investments in infrastructure. There are people who say that India’s foreign policy is to please every nation. India is careful not to cause any problems with China and the United States in particular. People in Japan often describe India’s diplomacy using the word “nonalignment.” But nonalignment has now become a myth. A scholar in Australia described India’s diplomacy as diplomacy for fishing in troubled waters. That description is closer to the true picture.

Kawashima: Sino-Indian relations have experienced several turning points, haven’t they?

Horimoto: Relations between the two countries had cooled following a border confrontation in 1962 in which India was humiliated. That changed in 1993, though the humiliation as a part of its collective national memories vis-à-vis China lingered. China and India signed the Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas and agreed to the policy of advancing their economic relations by leaving the border dispute to their special representatives at a high level; in other words, leaving the matter on the shelf. China and India are continuing to discuss the border dispute because they face domestic and international compulsions if they do not. But those talks have produced virtually no result as far as I can see.

Kawashima: From a Chinese point of view, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 were one turning point for its diplomacy in Asia. Western countries imposed economic sanctions on China after the incident. Under the circumstances, China succeeded in reversing the state recognition of countries that had originally recognized Taiwan, such as South Korea, Singapore and Brunei, to China. Almost all countries surrounding China recognized the government of the People’s Republic of China as a result. This situation became the foundation for China’s current diplomacy for the surrounding countries. In addition, China worked to solve its border disputes in the 1990s. China solved border disputes with Russia, with which it has a long border, countries in Central Asia such as Kazakhstan, and Vietnam. China did this because trans-border trade is essential to the economic development of its frontier provinces, such as Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. The country succeeded in almost all negotiations. The only disputes remaining were those over the land and sea borders with India.

Horimoto: I suspect that China is leaving those disputes unsolved on purpose.

Kawashima: That may be the case.

Horimoto: In short, China wants to have cards remaining; cards it can use for anything at any time. Perhaps, India too. In addition, China does not want adverse effects on the Tibetan issue because border disputes with India inevitably involve the issue.

Kawashima: Speaking of Tibet, the water in the Ganges River has been a problem recently, hasn’t it?

Horimoto: It has been a huge problem. The Brahmaputra River originates in the Tibetan Plateau and flows into the Bay of Bengal after joining the Ganges River in Bangladesh. China is currently building dams at 20 sites along the Brahmaputra River. Countering protests by India, China is explaining that they are flood mitigation dams used solely for generating power. But that is not true as a matter of course. When the water in the Brahmaputra River is dammed…

Kawashima: The downstream areas experience disadvantages.

Horimoto: For India, the Tibetan issue is no longer about the Dalai Lama, as it used to be. It is now a water issue. There is a proverb in China that states, “Two tigers cannot live together on a single mountain.” China scholars in India cite this proverb to explain China’s hostile view of India. In short, they argue that China is attempting to build an Asian order based on its unipolar domination by confining India to South Asia.

Kawashima: China attempts to make its neighbors follow the Chinese rules to the end, instead of embracing orders in other regions. And China maintains that the Chinese rules are fair and open.

Horimoto: After all, China can play the game by the Chinese rules only.

Kawashima: That’s right. China’s basic stance is to expand the application of its rules. What is India’s position regarding this point?

Horimoto: Generally and historically speaking, India tends to be accommodative. . Not many people in India show strong reactions against foreign countries. This tendency may be the result of the foreign rule that the country experienced twice: firstly by Muslim forces in the 12th century and secondly by Britain in the 18th century.

Kawashima: Compared with the diversity of India, I feel that China is a relatively homogenous society.

Horimoto: China absorbs and assimilates all comers. It did so when Genghis Khan arrived and when the Qing dynasty moved in from Manchuria. India might be the same.

Is it Possible for Japan to Keep China in Check in Partnership with India on a Sustained Basis?

Kawashima: I think two game changers called China and India will appear in the same region of Asia, although there will be a time difference in their emergence. There will be a clear time lag between the peak time for China and that for India. China will reach the peak first, and India will do so subsequently. The question is how long the time lag will be. Will their peaks arrive in time to realize replacement? Or will the two powers join forces to confront Western nations? Another question is what Japan will do. It will be good if Japan can form a team with India and keep China in check. However, a major problem will arise for Japan if India considers it a better idea to form a team with China, instead of Japan.

Horimoto: The current relationship between Japan and India is a marriage of convenience like many instances of important bilateral relations in the past. In other words, they married each other for their respective convenience. They are maintaining friendly relations because they need each other at the moment. Their relationship may change from now on. Indo-Japanese relations are bound to undergo changes too, if and when India grows bigger than China in 10 years’ time.

Kawashima: I agree with you completely. China will move closer to India when its power declines. In 2050, Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan will be countries of old people. I think that the center of Asia will shift from East Asia to regions such as South Asia, and the power balance between China and India will change.

Horimoto: Speaking of the near future, leaders from Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) will hold their summit conference in Xiamen, China in early September 2018. By that time, China and India must do things that will be sufficient for each of them to excuse themselves domestically over the tensions in Bhutan.

Kawashima: Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo is planning to visit India in mid-September 2018 as well.

Horimoto: I think that the policies toward China and the Indian Ocean will be on his agenda. Japan-India relations are likely to grow closer and closer for some time to come.

Translated from “Tokushu ‘Shu Kinpei no kenbo,’ Taidan: Chugoku to Indo ryoyu narabitatsu hi wa kuruka (Feature Article – The Machiavellianism of Xi Jinping, Dialogue: Will the Day Come When China and India Coexist as Major Powers?),” Chuokoron, October 2017, pp. 132-139. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [October 2017]