System reforms for improving agriculture: A Vision for Digitalizing African Agricultural Infrastructure Based on Farmer Unionization

New Challenges in African Business

Goda Makoto, CEO of Nippon Biodiesel Fuel Co.

Starting with Ninomiya Sontoku’s hotoku shiho and Ohara Yugaku’s Senzokabu Association, which revived ruined farm villages at the end of the Edo period, Japan underwent a technological evolution going from the Cooperative Society Law enacted in 1900 (Meiji 33) to the agricultural cooperatives, cooperative associations, credit unions, and shinkin banks of today. The creative foundation of our business is about incorporating those experiences in spreading digitalized agricultural unions and marketplaces in countries in Africa. The cooperative membership rate (to population) in Sub-Saharan Africa is 2.73%, which is extremely low compared to 45.55% in Europe and 38.63% in North America. Looking at pick-up arm types, agricultural development agent types, farmland reform receptacle types, and cooperative sales organization types, the roles played as well as failures and successes recorded by agricultural cooperatives in African countries have varied, and the interconnections between nationalism and development contexts are complex. Also in Asia, there are countries where Japanese-style agricultural cooperatives fit in and where they do not.

Even so, structural reforms and market liberalization are happening in African countries, and TICAD also wants to see companies launched with development assistance. At the same time, market liberalization is facilitating the spread of information asymmetry between middlemen and individual farmers. As suggested by the African Union’s Agenda 2063, Aspiration 6: “Development is people-driven,” perhaps now is the right time for making meaningful support to help farmers autonomously sell jointly, purchase jointly, and create credit as mutual aid, which is the starting point of agricultural cooperatives, for the sake of improving their own living.

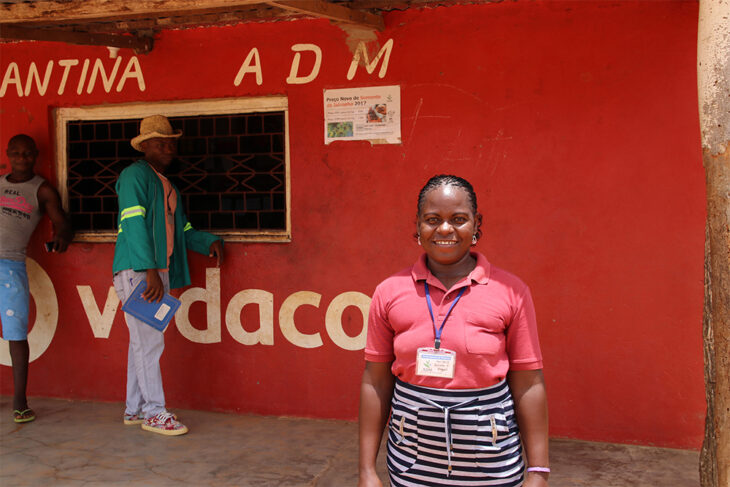

In the case of Mozambique, cell phones became usable in the farm villages in 2013. We introduced e-money in the north of Cabo Delgado Province where we have been working since November of the same year. Also when purchasing the produce and selling it at kiosks, we transfer value using contactless smart cards. This allows for the accumulation of a record of who sells what, when, and for how much to the company as well as who buys what, when, and for how much from the company. Based on that income and expenditure information, we give small loans to individual farmers and I believe this has shown that credit creation is possible also for small farmers in farm villages without electricity that have previously lacked access to information finance.

Nippon Biodiesel Fuel has introduced an e-money system in Mozambique. Users hold up their IC cards.

Nippon Biodiesel Fuel has introduced an e-money system in Mozambique. Users hold up their IC cards.

ALL PHOTOS: COURTESY OF NIPPON BIODIESEL FUEL

However, this presents two challenges. The first is that even if individual famers manage to create credit, the limit for such individual small farmers is about 50,000–100,000 yen. The second is that horizontal expansion is difficult in the case of direct purchasing and selling. There are more than 10,000 villages just in Mozambique, so it is difficult for us to manage produce purchase points and kiosks for all of them.

A first way to overcome these challenges is to organize individual farmers into agricultural collectives, which would make possible something like loans of 5–10 million yen per group of 100 persons. The aim is for this to allow cooperatives to buy trucks and directly transport produce to markets or buy tractors and expand the arable land. This can also expand the business opportunities for Japanese companies.

A second way is cooperating to build an online market for transacting produce and agricultural materials, known as the Virtual Farmers Market (VFM) of the United Nations World Food Program (WFP), with the aim of new credit creation that does not require us to purchase the produce, but is possible by accumulating data on the many other middlemen’s transactions across the country. Organization is important also in this case. Even if an individual farmer wants to sell 5 kg of produce and he cannot find a middleman to take it to the collection point 300 km away, a cooperative can gather 5 tons of produce and sell it altogether, which allows them to participate in VFM transactions.

|

|

| A Nippon Biodiesel Fuel representative (blue shirt) explains how to use the e-money system. | A kiosk staff member stands in front of one of numerous kiosks built by Nippon Biodiesel Fuel in rural areas of Mozambique |

In the future, we want to use the insights gained in Mozambique to provide digitalization that can enhance support for forming and managing agricultural cooperatives as well as market access. This will be a project that contributes both to further promoting the empowerment of agricultural workers, which is a priority area in the Yokohama Declaration and the Yokohama Action Plan, and to Japanese companies’ expansion in Africa.

Translated from “Afurika bijinesu—tsugi no itte: Nogyo kaizen no tameno sisutemu kaikaku—Nominkumiai-ka wo dodaitoshita Afurika nogyokiban dejitaruka koso (Business in Africa—The next step: System reforms for improving agriculture—A Vision for Digitalizing African Agricultural Infrastructure Based on Farmer Unionization),” Gaiko (Diplomacy), Vol. 55 Jul./Aug. 2019 pp. 46-47. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [August 2019]

Keywords

- Digitalizing agricultural infrastructure

- agricultural unions

- agricultural cooperatives

- agricultural collectives

- Africa

- Mozambique

- e-money

- Virtual Farmers Market