Toward New Solidarity in Global Health: Universal Health Coverage and Reform at the WHO

As COVID-19 infections spread across the world, the question of how vulnerable health and medical systems in developing countries will weather the crisis is an urgent issue. We track new approaches and the progress of a health diplomacy based on Universal Health Coverage.

(The interview was held on January 6, 2021 and the transcript was finalized on January 19.)

Dr. Ezoe Satoshi, Director, Global Health Policy Division, International Cooperation Bureau,

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Interview by Nakamura Kiichiro, editor-in-chief, Gaiko (Diplomacy)

——Dr. Ezoe, until August 2020 you were mainly overseeing global health at the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations in New York.

Dr. Ezoe Satoshi

Dr. Ezoe Satoshi: In January 2020, we had reports from Wuhan in China of an outbreak of infection. By February, the spread of infection on the Diamond Princess was widely reported in Japan, but in New York the initial perception was that the problem was primarily an Asian one. However, by mid-March, the number of positive cases in New York had risen rapidly. Even in April, after the lockdown, there were ten thousand new cases a day in the state of New York, and on some days the number of deaths exceeded one thousand, so the situation was quite serious. In New York, 42nd Street (where the UN is located) was completely deserted even in the middle of the day. It was truly a strange sight. The United Nations (UN) was also physically closed, but since there were countless virtual meetings, I was constantly busy attending meetings or conducting negotiations from home.

——Please tell us about the developments at the United Nations and the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations.

Ezoe: As a result of the global spread of COVID-19, masks and medical tools were in short supply around the world. We also started hearing outcries about such shortages, so figuring out a response became an urgent issue for the UN.

In March 2020, the UN launched the COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). The Japanese government has been quick to provide more than 170 billion yen (1,496 million US$) in COVID-19-related support to the health and medical sectors in vulnerable countries with fragile health and medical systems through bilateral assistance and international organizations. In addition, the Japanese government is also ready to provide international yen loans of a maximum 500 billion yen throughout fiscal 2022. The support has been welcomed by the international society and developing countries because it is on a scale that will have an impact.

While measures to control the immediate spread of infections are important, this is also a moment of renewed recognition of the importance of universal access to affordable health and medical services worldwide. We also feel that we have to use this opportunity to look at specific support the international society can provide to make Universal Health Coverage (UHC) a reality. UHC is the concept and the policy that forms the foundation for Japan’s global health diplomacy. It is a medium- to long-term initiative, but it is also an urgent issue in the sense that it is directly linked to COVID-19 response.

——Japan has worked hard on global health diplomacy for some time now.

Ezoe: Global health cooperation is a strong area for Japan. It is one of the pillars of Japan’s diplomacy, one that is backed by the knowledge and persuasiveness stemming from a society that has achieved economic growth as well as one of the healthiest population with longevity including through the national health insurance system, the Japanese version of UHC, and a long track record of bilateral and multilateral assistance. The topic of infectious disease was covered at the G8 Kyushu-Okinawa Summit in 2000. The issue of strengthening health systems was addressed at the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit in 2008. The Strategy on Global Health Diplomacy was formulated in 2013, and in 2015 the government formulated the Basic Design for Peace and Health. In the same year, Japan made a strong case for incorporating UHC in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the UN General Assembly. H.E. Abe Shinzo, Prime Minister at the time, has contributed two articles about Japan’s vision to the well-known medical journal The Lancet (Japan’s vision for a peaceful and healthier world, and Japan’s strategy for global health diplomacy: why it matters). The former Prime Minister also led discussions about UHC at high-level international conferences including the G7 Ise-Shima Summit in 2016, the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD VI), the UHC Forum 2017, the G20 Osaka Summit in 2019, and TICAD VII.

UHC Taking Root at the UN under Japan’s Leadership

——Global health policy is mainly discussed at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva. What is the relationship with New York?

Ezoe: Technical issues are discussed by health ministers from all member states at the World Health Assembly. However, in recent years, financial resource mobilization, the development of legal systems, and many other issues have required whole-of-government engagement. The established trend over the past twenty years has been that heads of state have committed to handling important health issues at the UN General Assembly. The United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS (UNGASS) in 2001 was the first High-Level Plenary Meeting on health issues organized by the UN. Subsequently, meetings have dealt with themes such as non-communicable diseases (referred to as lifestyle-related diseases in Japan) in 2011, antimicrobial resistance in 2016, tuberculosis in 2018, UHC in 2019, and COVID-19 in December 2020. Starting with the resolution on AIDS in 2000, discussions at the UN Security Council have also addressed health issues, including the Ebola virus disease in 2014 and 2018, and COVID-19 in July 2020.

——How did it function at the working level in UN?

Ezoe: In the case of the UN High-Level Meeting on UHC in September 2019, we were directly involved from concept to organization and agreement on the leaders declaration (Political Declaration). In December 2018, Japan established a group called “the Group of Friends of UHC and Global Health” with member states with an interest in UHC. Then Ambassador Bessho Koro, Permanent Representative of Japan to the United Nations, chaired the meeting, the purpose of which was to deepen understanding among UN members the importance of achieving UHC around the world by 2030 as depicted in the SDGs. On that occasion, the sense of trust in Japan and the network we had built when Ambassador Bessho successfully facilitated the UN High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis in 2018 proved useful. In fact, seven countries showed an interest at the start, but the number has grown to more than sixty-five countries. As a result, the High-Level Meeting in UHC agreed on a Political Declaration with the ambitious goal of “progressively covering one billion additional people by 2023 with quality essential health services” and “providing measures to assure financial risk protection and eliminate impoverishment due to health-related expenses by 2030”, with special emphasis on the poor as well as those who are vulnerable or in vulnerable situations. Then Prime Minister Abe was the only head of state and government invited to the closing ceremony of the High-Level Meeting where he once again made a global appeal for UHC while referencing Japan’s experience with the national health insurance system as Japan’s UHC. (A case study on the UN High-Level Meeting on UHC is available here (page 235-252).)

On September 23, 2019, then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo (front row, second from left) addressed the closing session of the UN High-Level Meeting on UHC. Bessho Koro (back row, third from left), then Ambassador Permanent Representative of Japan to the United Nations, is sitting behind Abe. H.E. Tijjani Muhammad Bande, President of the 74th Session of the United Nations General Assembly (front row third from right), Director General Tedros of the WHO (front row right hand side), Ms. Melinda Gates (front row left hand side) also participated in the session.

Photo: Cabinet Public Relations Office

——This is also linked to the response to the coronavirus, isn’t it?

Ezoe: Co-chaired by Ishikane Kimihiro, Japanese Ambassador to the United Nations, the Group of Friends has continued to convene online meetings since May 2021. Confirming the importance of UHC, the Director-General of the WHO, the Deputy Secretary-General of the UN, the President of the UN General Assembly, and from the Japanese side, Takemi Keizo, Member of the House of Councilors and WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Universal Health Coverage, have all addressed the meetings. It is significant that the Secretary-General of the UN and the Director-General of the WHO have backed the increased importance of UHC amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsequently, we asked the Secretary-General of the UN to issue a Policy Brief on COVID-19 and Universal Health Coverage. When the Brief was released, Japan compiled a statement of support that was endorsed by 120 countries.

Unlike Geneva, there are not so many health experts among the UN officials and Missions in New York. By creating the Group of Friends and working hard on the process of deepening understanding, we have not only increased trust in Japan and enhanced understanding of UHC, but we have also created personal connections in the global health field. I also believe that the UHC input provided to world leaders and high levels of UN agencies has influenced the smooth rollout. Without the Group of Friends and the High-Level Meeting, I believe quite a few countries would still be asking “UHC? What is it?”

——When [then] Prime Minister Suga delivered his statement to the 75th Session of the UN General Assembly via video in September 2020, he devoted a significant amount of time to discussing COVID-19 measures and global health.

Ezoe: As well as presenting the goal of making UHC reality while leaving no one behind based on principles of human security, Prime Minister Suga placed particular emphasis on three areas. Firstly, “to safeguard lives from COVID-19, Japan fully supports the development of therapeutics, vaccines and diagnostics, and works towards ensuring fair and equitable access for all, including those in developing countries.” Secondly, to prepare for any further spread of COVID-19 and future health crises, “Japan is committed to expanding its efforts in developing countries to build hospitals as well as to assist strengthening health and medical systems through providing equipment and supporting human resource development.” Thirdly, to take measures “to ensure health security in an even broader context […] such as improving the conditions of water, sanitation and hygiene, nutrition and other environmental factors.”

As well as moving forward in these areas, Prime Minister Suga announced that Japan has provided foreign aid of over 170 billion yen to the medical and health sectors (the figure became approximately 430 billion JPY or 3.9 billion USD. See the updated summary as of September 2021). He continued to say that the WHO is key in our collective response to infectious diseases, but he also said that there is need for review and reform at the WHO, and that Japan will cooperate with this process.

——Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu co-hosted the Ministerial Meeting of the Group of Friends of UHC in October 2020.

Ezoe: In addition to cabinet ministers from the interested nations, the Secretary-General of the UN, the Director-General of WHO, the Executive Director of UNICEF, the Chief Executive Officer of Gavi (a global Vaccine Alliance), and the Executive Officer of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) participated in the meeting and confirmed development of “the countries’ capacity to tackle COVID-19, including ensuring equitable access to vaccines, and strengthening health systems in preparation against future health crises.” As well as stating that “Japan will continue to promote UHC and proactively lead international efforts with a focus on the above together with the international community,” Minister Motegi declared that “Japan will contribute more than 130 million USD to the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC)[1], in order to enable countries to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. This contribution is a part of Japan’s pledge of 300 million USD which was announced at the Global Vaccine Summit in June 2020.”[2]

The discussion about vaccines is a good example. Access to medical care and pharmaceuticals in developing countries is a core elements of UHC, but another important element is to continue with essential health services, such as non-communicable diseases, or maternal and child health. The COVID-19 pandemic has put pressure on UHC even in developed countries, so I believe this is a good opportunity for international society to recognize its importance. To borrow the words of António Guterres, Secretary-General of UN, “No one is safe until everyone is safe.”

WHO Reforms Have Begun

——Criticism of the WHO increased with the spread of COVID-19.

Ezoe: At the time, the WHO explained that they did what they could as an organization given their mandate and the situation, but it is true that the WHO response, including the initial response and the timing of the declaration of a public health emergency of international concern, have met with doubts and criticism. Therefore, the member states attending the World Health Assembly in May 2020 agreed to carry out a robust review of the response. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response, which is external to the WHO, was established in September 2020 with an international panel of analysts and experts to conduct a comprehensive review. The WHO is also carrying out an internal review of the International Health Regulations, which are the international rules regarding public health crises such as COVID-19. Japan is actively cooperating with the initiatives. The outcomes will be presented to the member states as recommendations at the World Health Assembly in May 2021.

——Discussions about more fundamental WHO reforms are also underway.

Ezoe: What is the function of the WHO in the first place? The Constitution of the WHO defines its mission as “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health,” but one could summarize that, it is (1) leadership and coordination, (2) norm setting and technical guidance, (3) technical support and advice, (4) operations, (5) financing, (6) research and development. However, is it realistic for the WHO to have sole responsibility for all these elements today? An argument can be made for being more selective and focused. For example, points (1) to (3) should be reinforced because they can only be done by the WHO, whereas the WHO does not necessarily have to do everything involving points (4) to (6).

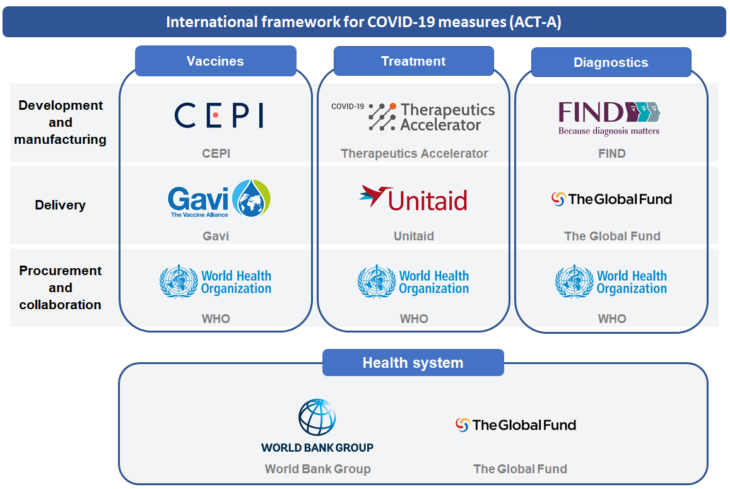

In this regard, I would like to draw attention to the ACT (Access to COVID-19 Tools) Accelerator (ACT-A). Launched in April 2020, ACT-A is an international framework that aims to accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to safe and effective vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics at a fair price. ACT is the joint proposal of nine countries and regions, including Japan, the WHO, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as other countries and organizations.

It is a framework that organizes international support for the COVID-19 response into the three pillars of Vaccines, Treatment, and Diagnostics, and shares the work among the international organizations and bodies that have the most expertise at each stage (see figure). For example, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations CEPI (a global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations) is responsible for the development and manufacturing of vaccines, Gavi handles delivery, while WHO is responsible for procurement and collaboration. I think this initiative shows one possible direction for the global health framework, one that includes collaboration between civil society and private sector, which is already common practice in global health.

——Looking at the COVID-19 era and the post-COVID-19 era, how should global health diplomacy move forward from here?

Ezoe: International approaches in the health field have evolved from “tropical medicine,” which studies diseases in the tropical areas, to “international health,” which has added the broader perspective of international cooperation with developing countries. In recent years, the concept of “global health” as a global-scale issue common to developing and developed countries has become the mainstream in the context of globalization, stressing the importance of global health diplomacy. The COVID-19 pandemic is a strong reminder that health issues are not only issues for developing countries or health authorities, but also global diplomatic issues concerned with security, economy and development, including in the developed countries in the West where the pandemic is particularly virulent. Rebuilding the global health architecture and governance is a pressing issue amid the conflict between unilateralism and multilateralism. At this time, the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP) announced the Proposal for Japan’s global health diplomacy in the post-COVID era to boost the presence of global health diplomacy based on relevant policy recommendations.

The healthcare field, which deals with people’s lives, has properly been regarded as the foundation for international cooperation and trust-building among nations. As a country that has built trust based on healthcare, I feel that the real test will be whether Japan can turn this crisis into an opportunity for international cooperation by mustering the knowledge and resources of the international society, the public and private sectors.

Translated from “‘FOCUS Korona-kiki kokufuku no mitorizu’ Kokusaihoken wo meguru aratana rentai e—yunibasarru herusu kabarejji to WHO kaikaku, Gaiko (Diplomacy) Vol. 65 Jan./Feb. 2020 pp. 100-105. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [October 2021]

[1] COVAX is one of three pillars of the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, which was launched in April by the World Health Organization (WHO). COVAX is co-led by Gavi (The Vaccine Alliance), the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and WHO. Its aim is to accelerate the development and manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines, and to guarantee fair and equitable access for every country in the world. All participating countries, regardless of income levels, will have equal access to these vaccines once they are developed. The COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC) is to ensure that the 92 middle- and lower-income countries that cannot fully afford to pay for COVID-19 vaccines themselves get the same access to COVID-19 vaccines as higher-income self-financing countries and at the same time.

Source: https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press4e_002929.html

[2] Japan later co-hosted the COVAX AMC Summit on 2 June and pledged to contribute 1 billion USD to COVAX AMC and to share approximately 30 million COVID-19 vaccine doses (which was increased to 60 million September 2021). The COVAX AMC Summit succeeded in mobilizing more than 8.3 billion USD in total to cover 30% of the eligible population in developing countries. Source: https://www.mofa.go.jp/ic/ghp/page1e_000326.html; https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/world-leaders-and-private-sector-commit-protecting-vulnerable-covid-19-vaccines

Keywords

- Dr. Ezoe Satoshi

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- COVID-19

- Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations

- UN launched the COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan

- Universal Health Coverage

- UHC

- global health diplomacy

- national health insurance system

- Strategy on Global Health Diplomacy

- SDGs

- TICAD VI

- UHC Forum 2017

- WHO

- Group of Friends of UHC and Global Health

- Policy Brief on COVID-19 and Universal Health Coverage

- UNICEF

- CEPI

- Gavi

- Therapeutics Accelerator

- FIND

- Unitaid

- The Global Fund

- World Bank

- COVAX Advance Market Commitment

- Access to COVID-19 Tools

- ACT

- ACT Accelerator

- post-COVID era