Inward-looking China and the Decline of Belt and Road Initiative

Uncertainty about the future caused by domestic and international factors has the potential to significantly change China’s former foreign investment and financial aid policy, as represented by the Belt and Road Initiative, in the medium to long term.

Map: MicroOne / PIXTA

How should the international community face up to a superpower that is growing increasingly inward-looking due to the US-China conflict, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Ukrainian war?

Kajitani Kai, Professor, Graduate School of Economics, Kobe University

Prof. Kajitani Kai

As COVID-19 continued to spread in early 2022, Shanghai City in China entered a total lockdown on March 28. The lockdown lasted more than two months. The outside world found out from social media that many residents were exasperated and stressed by uncertainty about the future, and that the lockdown delayed distribution and caused difficulties with food deliveries. By June, the lockdown was finally lifted, but activities remain heavily restricted.

Even if they do not go as far as total lockdown, many cities implement a policy of dynamic zero-COVID whereby, if a single infected person is found in an apartment building, residents are not allowed to exit the building until there are zero new infections. Questions have been raised not only overseas, but also in China, about the stance of the Xi Jinping administration, which seems unable to disregard the experience of past success and remains committed to the zero-COVID policy even in the case of the highly infectious omicron strain that is less likely to cause serious illness. Meanwhile, it remains be seen what compromises will be made with regard to reorganizing supply chains due to the US-China economic friction that predates the COVID-19 pandemic. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the subsequent economic sanctions imposed by the West is another major uncertainty factor for the Chinese economy.

What impact will the growing uncertainty caused by these domestic and international factors have on the future of the Chinese economy? This article focuses on the potential for such opacity about future prospects to significantly change China’s former foreign investment and financial aid policy, as represented by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in the medium to long term. The article also considers how this would impact the world economy.

The cost of adhering to a zero-COVID policy

The economic statistics for April 2022, published in mid-May, revealed the negative effect of the lockdown of major cities due to the zero-COVID policy on the economy as a whole. Consumption was hardest hit with retail sales for April dropping by 11.1% compared to the same period in the previous year, the first decline since January 2020.

In terms of production, mining and manufacturing recorded a year-on-year decline of 2.9% in April. In addition, cumulative investment in fixed assets from the start of the year to April rose by 6.8% year-on-year, a significant drop from the 9.3% increase achieved in the period to March. Reflecting the decline in both supply and demand, a nationwide survey in April found that the unemployment rate had deteriorated to 6.1%, topping 6% for the first time in the two years since April 2020. If the numbers are narrowed down to the 16-24 age group, the unemployment rate for the same period is 18.2%, suggesting that young people are particularly vulnerable to insecure unemployment. It is conceivable that the successive lockdowns of Xi’an, Shenzhen, Changchun and Shanghai not only depressed production and consumption in those cities, but also impacted on the economy as a whole through distribution interruptions, and other reasons.

Professor Zheng Song of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who analyzes and researches trends in the Chinese economy, published a paper in April 2022 in which he and his team analyzes the impact of lockdown on economic activities based on GPS information collected from long-haul trucks in the period from April 2020 to January 2022. According to the analysis, if a city enters lockdown for a period of one month, the number of trucks entering and leaving the city is cut by about half. If the four major Chinese cities (Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Shenzhen) are placed in lockdown for one month, real income in the four cities would be reduced by 61%. The real gross domestic product (GDP) for the whole country would shrink by 8.6%, of which 11% would be spillover effect to other areas. The negative effect would be even greater if you added in the dampening effect on long-term savings and investment.

In an interview with the economic magazine Caixin Weekly (April 18, 2022), Professor Song also suggests a projected loss of about 0.7% to GDP if even one of the four major cities is put into lockdown for one month.

The Chinese economy and greater domestic circulation strengthen inward-looking thinking

As the domestic and international risks to the Chinese economy increase, the stance of the Chinese government on economic policies is becoming increasingly inward-looking.

Greater domestic circulation is one of the important keywords indicating China’s shift toward introversion. At the meeting of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Committee in July 2020, greater domestic circulation was adopted as the main constituent of the new growth framework, which is to encourage domestic and international dual circulation. The motion for the 14th Five-Year Plan approved at the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (Fifth Plenary Session) in October 2020 defined greater domestic circulation as “More reliance on the strong domestic market, and more seamless connection of economic processes, such as production, distribution, circulation, and consumption, will help remove impediments to rational flows of factors of production, and contribute to supply-demand equilibrium, conducive to creating a virtuous economic circle.” This definition clarifies the characteristics of greater domestic circulation, which promotes supply-side structural reform through the marketization of production factors while cautioning against protectionism by local governments.

As early as March 2020, the Communist Party of China released a policy document entitled Opinions on Building a More Complete System and Mechanism for Market-oriented Allocation of Factors. The opinions on the five production factors of land, labor, capital, technical, and data emphasized the courses of action as (1) to ensure highly efficient market-based allocation, (2) to remove systemic factors that impede the free flow of production factors, and to promote the establishment and development of a market for production factors.

In January 2022, as a follow-up to the aforementioned opinions, the State Council published a policy document entitled Master Plan for the Pilot Program of the Comprehensive Reform of the Market-oriented Allocation of Factors, which clarified the concrete plans for marketization of the aforementioned five production factors. The policy document refers to efficient use of land through the marketization of the right to use land for industrial purposes, strengthening systems for evaluating the skills and techniques of workers, promoting a mobile labor market that leverages the skills of workers, and establishing systems to guarantee intellectual property rights for advanced technologies.

The content of this series of policy documents suggests that greater domestic circulation continues the supply-side structural reforms advocated by the Chinese government since around 2014, that is, promoting the mobility of production factors, and trends that aim for growth patterns that differ from extensive growth. The prolonged US-China conflict is also without doubt a factor that has strengthened the inward-looking attitude of the Chinese government. Xu Qiyuan, Senior Fellow at the Institute of World Economics and Politics, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, points out that the Chinese government has started to pay attention to the stability of value chains because of the prolonged US-China conflict.[1] For example, industries that rely on overseas for important intermediate goods imports are vulnerable to risks of economic sanctions imposed by the United States and other countries. How to develop alternative supply systems to prepare for such risks is an important topic under discussion.

With regard to industries where the vulnerability of value chains is of concern to China, in particular, electrical and electronics, machinery and equipment, plus optical and medical equipment, Xu et al. insist that China must rebuild value chains that incorporate the central and western regions of China rather than overseas. Specifically, Xu proposes policy schemes such as introducing a progressive tax system that varies by area, promoting corporate investment in the central and western regions, improving constraint mechanisms and incentives for local governments in the central and western regions, raising the level of marketization and local government efficiency, and improving relations between local governments and corporations. These ideas agree with the aforementioned greater domestic circulation advocated by the Chinese government. Specifically, it can be said that they support the inward-looking attitude of returning investment funds to China.

The Ukrainian war has hastened the demise of Belt and Road Initiative

It is possible that the growing inward-looking thinking with regard to economic policies discussed above will significantly change the nature of China’s foreign investment and financial aid policies represented by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Originally, the capital export type economic development strategy symbolized by the BRI was intended to mitigate excess supply capacity by “releasing” swelling foreign exchange reserves and domestic excess capital to overseas in the context of expectations for the renminbi (RMB) appreciation. Economic growth in emerging countries through foreign aid and direct investment by the Chinese government would also expand the market for excess production capacity in China.

However, the premise was already significantly shaken as the RMB depreciation trend continued after the inauguration of the Trump administration. In addition, analyses by experts in international finance suggest that the international situation after the Ukraine crisis will also cause severe headwinds for China’s foreign capital exports in the future.

For example, Yu Yongding, Senior Fellow of the Institute of World Economics and Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, an expert in international finance, has pointed out that the large foreign exchange reserves held by China have the potential to become a new risk factor in the future due to the financial sanctions against Russia by Western countries after Russia invaded Ukraine. If the United States freezes the dollar-denominated assets held by the central bank in China as they did to Russia, the value of China’s overseas assets could potentially be zero.

With regard to such risks, Yu’s recommendations to the policy authority is to reduce vulnerability through financial system reform, to introduce as much flexibility as possible in the exchange rate, to reduce the scale of foreign exchange reserves and to adjust overseas assets and debt structures, such as reviewing the cost of debt structures and reducing holdings of US government bonds, in addition to reducing the scale of cross-border capital movement.[2] His recommendations echo the Chinese government policy of pegging capital management on greater domestic circulation, while being selective about foreign investments and limiting them to those that are more effective.

A recent study by Sebastian Horn, Chief Economist at the World Bank, states that China’s overseas investment boom represented by the BRI is likely to be confronted with more serious obstacles due to the war between Russia and Ukraine.[3] The basis for the claim is the size of the loans by Chinese government financial institutions to Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. According to Horn et al., lending by China’s state-owned banks to Russia since 2000 exceeds USD 125 billion, and has mostly financed Russian state-owned enterprises in the energy sector.

China has also provided about USD 7 billion to Ukraine, mainly focused on projects in agriculture and infrastructure, as well as USD 8 billion to Belarus. These three countries together account for nearly 20% of China’s foreign loans over the past twenty years.

It has been pointed out that Chinese loans to emerging and developing countries, which have increased rapidly in recent years, may be vulnerable to default and other risks as the criteria for granting the loans are not clear. Horn points out that in 2010 the proportion of China’s foreign loans to countries experiencing debt crisis was approximately 5%, but has now increased to 60%. In many cases, these loans to developing countries have been granted by the China Development and the Export-Import Bank of China, or other government financial institutions, but the recipient countries have hardly been sufficiently vetted, and they have often been subject to restructuring and reorganization.

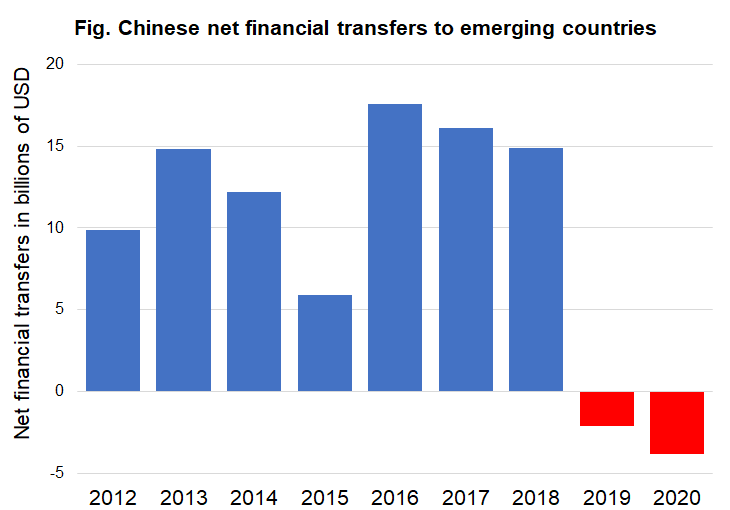

Note: This figure shows net transfers (new disbursements minus principal and interest payments) from Chinese bilateral creditors to public sector recipients in developing and emerging market countries.

Source: World Bank’s International Debt Statistics

In addition, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread worldwide, the G20 introduced the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), a common framework to support debt restructuring and address insolvency and liquidity issues, in order to temporarily suspend public debt repayments by the poorest countries. According to Horn et al., there has been a sharp increase in the number of debt restructurings for developing countries arranged by Chinese government financial institutions based on the DSSI framework since 2020. In actual fact, Chinese loans for emerging and developing countries, which peaked around 2015, clearly reached a watershed several years ago. For example, according to the World Bank International Debt Statistics (IDS), the net transfer of funds from China to government departments in low income and middle income countries has decreased from the peak in 2016, turning negative in 2019 and 2020 (see Fig.). Based on this data, Horn et al. point out that China’s state-owned banks have already become debt collectors rather than providers of funds for growth.

Interestingly, 2019 coincides with President Xi Jinping’s frequent remarks about a shift to high quality development with regard to BRI. In short, it could be said that for several years already reality has been quite different from the initial image of BRI as diverting funds to emerging and developing countries irrespective of the situation with domestic surplus funds.

This trend is likely to accelerate due to the risks posed by the Ukraine crisis and the subsequent economic sanctions confronting the economies of Russia and its allies. Chinese government financial institutions may compensate for the risks of future loans to Russia and others turning into bad debt through debt collection or by suspending new loans to high-risk debtor countries. Such impact has the potential to become a far bigger problem than the Debt Trap brought on by BRI which is widely discussed in the West.

How to deal with a shortage of capital in emerging countries

This paper takes the view that the inward-looking attitude of the Chinese government is likely to become more pronounced as a result of the zero-COVID policy, the US-China conflict, the Ukrainian war, and other domestic and international risks. In particular, aggressive fund turnover by both the public and private sectors in China, as represented by the Belt and Road Initiative, is likely to be curtailed in the future. This may slightly alleviate the sense of alarm in the international community, which views the BRI as a challenge to the existing economic order. However, an increasingly inward-looking attitude in China, which already has a strong position as a superpower in the world economy, may bring other risks to the international community. For example, how do we support sustainable economic growth in emerging countries if China withdraws from its role as a generous provider of funds?

Here, we may need to recall the tumult when the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was set up in 2015. At one time, there were warnings that the AIIB challenged the international financial order led by the United States, but as a result of participation by more than 100 countries, including European countries, the AIIB as an international organization has been compelled to focus on transparency, and is currently approving loans that are quite far removed from the intentions of the Chinese government. On the other hand, the performance of AIIB lending is far inferior to that of its predecessor, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the lack of competence is undeniable. Originally, the starting point for the AIIB vision was that existing international financial institutions did not adequately address the infrastructure demands of emerging countries. If so, as China takes an increasingly inward-looking attitude, now is the time for the international community to return to the starting point and, in cooperation with China, to seriously address the issue of how to solve the shortage of funds confronting emerging countries. The role of Japan, which already has a wealth of experience in aid to emerging and developing countries, should definitely not be minor.

Translated from “Chugoku no Uchimukika to ‘Ittai-ichiro’ no Suitai (Inward-looking China and the Decline of Belt and Road Initiative),” Voice, August 2022, pp. 77–83. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [August 2022].

Keywords

- Kajitani Kai

- Graduate School of Economics

- Kobe University

- Belt and Road Initiative

- US-China conflict

- COVID-19

- zero-COVID-19

- lockdown

- Russia

- Ukraine

- domestic circulation

- inward-looking

- investment funds

- loans

- bad debt

- developing and emerging market countries

- capital shortage

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)