Three-Way Discussion: Why Should We Discuss the Global South Now?

Light and shadow of Mumbai, the financial capital of India. Former ADB President Nakao Takehiko points out three reasons why we should focus on the South: in the case of Asia, the size of its economy, its relevance to global issues, and its political and economic system.

Photo: Andrey Armyagov / PIXTA

With the world heading toward division due to the logic of the major global powers, we should turn our attention once again, not to Europe and the United States, or China and Russia, but to the emerging and developing countries—with their multilateral dynamics, working on multiple levels—as key players in population scale, economic power, and order building.

Endo Mitsugi (Professor, University of Tokyo), Nakao Takehiko (Chairman, Mizuho Research and Technologies) and Kawashima Shin (Professor, University of Tokyo)

Prof. Kawashima Shin

Kawashima Shin: Over the last few years, the world has been undergoing major changes—with the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and accompanying global high prices, primarily for energy and food—and the impact is spreading globally.

Looking at international reports of Japan, however, most of the news is focused on the United States and China. Even when Asia and Africa are discussed, situations are typically depicted in the format of Europe and the United States vs. China and Russia, and there is an overwhelming tendency for developed countries and major countries to be the central focus.

I think there are certain limits to such a view. There are an overwhelming number of emerging and developing countries in the world that are not part of either Europe and the United States or China and Russia, which can be referred to as the Global South. International understanding that does not take the logic of these countries and regions into account presents an unbalanced reality.

Of course, emerging and developing countries do not act as one, and we must pay careful attention to the contexts of each country and region. But in any case, they are not just objects or pawns in the game of great power politics between the major global powers. They operate based on their own national interests or regional logic and tend to avoid zero-sum thinking such as “the United States or China.” I think that we need to understand the world from the perspective of these emerging and developing countries. That is my take on this problem.

Chairman Nakao Takehiko

Nakao Takehiko: That’s an important point. The areas in which advanced democratic countries can control the world’s political economy are growing smaller. In addition to economic scale, addressing global issues such as geopolitical issues and climate change is now meaningless unless emerging and developing countries are involved. What is even more concerning is the decreasing attractiveness of the “market economy” and “democracy” models that advanced democratic countries have been responsible for promoting.

Prof. Endo Mitsugi

Endo Mitsugi: Even in Africa, which is the region in which I specialize, there are various dynamics at work on multiple levels. Historically the region has been closely related to Europe, but in recent years China has also expanded its influence significantly, and North and East Africa are also strongly influenced by the Middle East. Russia’s influence is also large in its own way, as highlighted by the recent increase in attention, so the situation is becoming more complex.

Recently, the United States—the influence of which was less apparent under the Trump administration—has also been signaling moves to respond to Africa with China and Russia in mind, with the announcement of the US-Africa Leaders’ Summit to be held from December 13–15, 2022, and a US Strategy toward Sub-Saharan Africa published on August 8.

African countries and regions are each making proactive efforts to involve themselves in this situation. While I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it is multipolar, it is not a unipolar system by any means, and there are multiple complex dynamics at work.

It has all the elements for considering international politics

Kawashima: Mr. Nakao, as a former president of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), you have watched over Asia for many years. How do you consider the significance of seeing the world from the perspective of the Global South, and the importance of talking about the South—including the changes during that time?

Nakao: Before that, I think that one of the key points of contention when discussing Asia is whether to consider China as a member of the Global South…

Kawashima: The question of whether China is part of the South is subtle, and depends on one’s point of view. However, one aspect is that China itself considers itself to be the representative of the South, or at least its big brother, and is trying to focus its diplomacy there. China’s vision of the world is not China and Russia vs. the group of developed countries led by the United States, but rather the Global South led by China vs. the group of developed countries led by the United States.

As I said earlier, though, emerging and developing countries don’t like the zero-sum thinking of China or the United States, and don’t just follow China.

Nakao: China itself still claims to be a developing country, and in fact still has the poverty and backwardness of a developing country. At the same time, though, in economic, military, and technological terms it is already a major global power, and is strengthening its hegemonic behavior. China itself needs to recognize that it is seen—and feared—as a great power on par with the United States, and act responsibly.

I would like to summarize three reasons why we should pay attention to the South, from my perspective of having been involved with Asia for many years. The first reason is the size of the Asian economic scale.

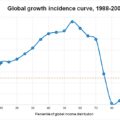

According to Asia’s Journey to Prosperity: Policy, Market, and Technology over 50 Years (published by the ADB in January 2020 and can be downloaded from the ADB HP), in 1960, Asia—including Central Asia but excluding the Middle East, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand—accounted for only 4% of the world’s GDP. In 2018, that share grew to around a quarter, and is on par with the United States and Europe.

If the GDP of Japan, Australia, and New Zealand is added to that figure, it increases by another 6–7%. At the same time, cutting-edge technologies are being created in countries throughout the region, and there is a possibility that some economies could leapfrog. East Asia is leading the way, and the scope of growth is now expanding to Southeast Asia and South Asia.

The second reason relates to global issues. This is an area that cannot be addressed without the cooperation of emerging and developing countries, but the interests of both sides often conflict. For example, climate change has dire implications for the countries of the South, including disasters, droughts and rising sea levels. Of course, they are willing to contribute to decarbonization, but at the same time access to energy is essential for economic growth, and there is a sense of distrust that the West—which has grown ahead of these countries with a lot of emissions historically—will take the lead.

The third reason is political and economic systems. Universal values of the West, such as marketization of the economy and democratization of politics, are not necessarily shared on the same level. The global spread of the market economy has brought prosperity to the world in general, including the least developed countries, and China is one example of a country that has reaped the rewards of that. But the question of whether that can be linked to the democratization of politics is another matter. I had thought that these countries were basically moving towards democratization and the expansion of civil liberties, but some countries—for example, Myanmar—have gone in the opposite direction, and in China the Communist Party has become more influential again recently.

Of course, marketization and democratization are important, but the processes leading up to them and the circumstances of each country differ greatly, and there is no single model that is the “right” answer. On one hand, China has begun to be recognized as an example of a new development model, while on the other hand Western countries that have displayed the conventional model are experiencing malfunctions, of a sort, including declines in economic performance and the division of domestic societies. In the United States, rioters even stormed the Capitol.

Kawashima: That’s exactly the case with the expansion of economic scale in ASEAN countries. In China, too, ASEAN countries are beginning to occupy a larger volume of the trade structure. In response to climate change, China is building a model in which it responds to global issues with a different logic than developed countries—including the green economy—and attempting to share it with other Asian countries and developing countries around the world. The story with marketization and democratization is similar, with China attempting to display a different development model from that of developed countries. So, China is, in a sense, aware of the importance of the Global South, and is trying to take advantage of it.

Endo: The point raised by Mr. Nakao is also important in Africa. While Africa it is not comparable to Asia in terms of economic scale, it has basically continued to display positive growth since the beginning of this century, at least from a macro perspective. China’s influence on its growth has been significant, and full-scale investment and aid from China—which began in around 2003—became one of the starting points. So, [the African economy] is essentially linked to trends in the Chinese economy. In 2016, when the growth of the Chinese economy slowed, so too did growth in Africa. The African economy itself is dependent on resource exports, so this is largely unavoidable. In fact, Africa experienced its first year of negative growth (this century) in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but has since returned to positive growth as of 2021.

One thing in particular to note about Africa is its population growth. According to UN projections, the current population of 1.5 billion will grow to two billion in 2040. Energy demand is expected to increase by around 60%, and there are concerns about food shortages. In recent years, some African countries—such as Ethiopia—have become self-sufficient in terms of food supplies, but most are still dependent on imports. Earlier, Mr. Nakao mentioned global challenges. The same also applies to food and energy, and I think that Africa’s population growth will also have a major impact on global supply systems in that respect.

Kawashima: What about the issue of democratization?

Endo: In terms of political systems, data from Freedom House indicates that democracy has declined in Africa in recent years. Certainly, Benin and Senegal—which were once the “honor students” of West Africa—can be seen to be retreating from democracy. In Mali and Burkina Faso, also in West Africa, there are moves to strengthen the power of military leadership authority, with frequent coups taking place. However, the reason for the setbacks here is the state of democracy as a political system, and it is not that African people dislike democracy as an idea. In fact, we can see some of the key values that make up democracy are already firmly ingrained. People want respect for human rights, don’t want one-party rule, and show support for banning candidates from running for three presidential terms.

Kawashima: I would also like to ask about development. Mr. Nakao, you have been involved as a financial stakeholder. During this time, I think that there have been major changes in development in Asia.

Nakao: For Asian countries, which have grown to a certain level, the importance of foreign development aid is declining. Originally, support such as bilateral aid (loans and grants) from Japan and other countries, and support from international financial institutions such as the World Bank and ADB was important for many Asian countries, but domestic development was funded mainly by domestic savings. In recent years, Asian countries have improved their expertise and technologies in areas such as infrastructure, and large loans are no longer necessary.

Some exceptional cases include large aid flows from China, such as those to Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In the case of Pakistan, fiscal expenditure was increased recklessly with each change of government, leading to a balance-of-payments (BoP) crisis. The IMF has repeatedly lent foreign currency to Pakistan, on the condition of adjustment policies. Sri Lanka, socialist economic management and a long-term civil war have caused political turmoil and economic exhaustion.

That’s where Chinese funding comes in. The problem is that the lender, China, is not a member of the Paris club (a group of creditor countries that monitors national debt and negotiates debt rescheduling—i.e., change of repayment terms—as necessary), and has made large-scale loans while ignoring the borrowers’ ability to repay them. In particular, under China’s “Belt and Road” policy, money has been lent easily through the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China and various Chinese state-owned enterprises without considering the economic viability of the projects, creating a so-called “debt trap” situation. While I don’t think that China set this trap deliberately, it will exhaust not only the debtors but China itself, which will have bad debts.

Kawashima: What about Africa?

Endo: Earlier, I mentioned the impact of China’s economic expansion. At the same time, as China’s foray into African countries has intensified—as Mr. Nakao points out—there has been increasing criticism of massive loans that ignore repayment capacity and methods of using them to acquire key facilities, and a growing number of countries are recently taking a more cautious stance. In 2013, President Xi Jinping first traveled to Russia, followed by Africa (Tanzania, South Africa, and the Republic of the Congo). At that time, a large port development plan was launched in Tanzania. Some time after the COVID-19 pandemic began, however, President John Magufuli announced the cancellation of the project. Construction of Uganda’s airport was also cancelled. China is also fully aware of this, and at the eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) held at Dakar (Senegal) in 2021, funding was reduced from $60 billion to $40 billion.

Kawashima: We have seen by focusing on the logic and autonomy of the Global South—or considering the challenges being faced by Global South—whether in Asia and Africa, thoughts of binary opposition between developed and developing countries are relativized, and the overall picture and outline of the problems of the international community are clarified.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and Ukraine situation

Kawashima: Next, I would like to ask—what significance have major changes such as the COVID-19 pandemic during the last few years, or the Ukraine situation in 2022, had for the Global South?

Nakao: There is no doubt that both the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine situation are very tough issues worldwide. In addition to requiring countries to fight infectious diseases, the COVID-19 pandemic has also raised the question of how to sustain the economy. Countries have developed expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. Now, both the United States and Europe are working to deal with recovery in demand, labor supply constraints, and creaking supply chains due to confrontation with China. Energy and food price increases due to the situation in Ukraine are also an issue and have caused non-stop inflation, and countries have rapidly tightened their monetary policies. This caused a backflow of funds from emerging countries to developed countries, which is a major challenge for Asian countries.

Endo: With the COVID-19 pandemic, infections were more common and severe among the elderly, at least in the early stages, but Africa’s population is predominantly young. So, in the African continent overall, the number of infected people was 12 million and the number of deaths was around 250,000—which was not as much as initially feared.

However, countries such as South Africa initially placed very strict restrictions on movement, including lockdowns, highlighting various disparities. Earlier, I talked about economic growth in Africa, but even if this is true on a macro level, the disparity between rich and poor is widening at the micro level. For the poor, lockdowns were literally a matter of life and death, with frequent riots in demand for food. The Ukraine situation has caused similar hardships, with soaring food prices. Disparity itself is a structural problem, and issues such as educational opportunities and Internet access have an impact—expanding and reproducing poverty among those who cannot afford them. While this is a common structure in the global context, it is very evident in Africa.

Nakao: The widening of inequality is similarly a big problem in Asia. When foreign capital enters the country, they look for land, local partners, and local people who are well educated and speak English. In developing countries, workers’ wages rise because of the inflow of foreign direct investment—but landlords, conglomerates that have local experience and connections, and highly educated people become even richer. Education should have a redistributive function, but it is often a factor that promotes inequality. Widening disparities due to globalization and the adoption of advanced technologies, and stratification due to education are global issues, including in developed countries.

Kawashima: Why doesn’t the redistributive function work well?

Nakao: For both governments and companies to survive fierce international competition, it is difficult to raise taxes because companies and people flee the country. In terms of social thinking, the influence of social democracy, which emphasizes the redistributive function, is weakening.

Phases of confrontation over political systems

Kawashima: With COVID-19 measures being implemented, we often hear that authoritarian tendencies in national politics have grown stronger, or hear opinions recognizing the superiority of authoritarian regimes. Especially from Japan’s point of view, the conflict between developed countries vs. China and Russia over the Ukraine situation seems to be becoming increasingly apparent. Is there a growing perception toward dividing the world in two?

Nakao: Yes, there is a growing perception, but it doesn’t benefit anyone, and it won’t go straight in that direction. The Global South surely wants to avoid that at all costs. In recent years, there is growing awareness of economic security to avoid supply chain disruption and the need for restructuring production networks. To put it a little exaggeratedly, it could lead to a return to imperialist enclosures, or “blocs.” In that sense, the globalism that had been driving global economic growth is now being adjusted, becoming stagnant or partially receding. Shrinking of the foundation for growth is a big problem for the South.

Kawashima: In terms of responding to that, countries in Central Asia—for example—are part of the former Soviet bloc and seem to have common characteristics in regional and national responses. But do they tend to emphasize relations with Russia?

Nakao: As Prof. Kawashima said earlier, emerging and developing countries do not have the mindset of choosing one side or the other. They basically engage in opportunism to maximize their economic interests and other national interests. The close relationship of Central Asian countries with Russia is a consequence of historically strong political and economic ties with Russia, which simply makes them appear that way. In reality, they do not love Russia all that much, as was shown by the intense independence movements at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Also, even if China’s influence is growing it does not mean that these countries are uncritical of China’s behavior. I am sure that Islamic countries in Central Asia, for example, are concerned about the Uyghur problem. India, too, engages in joint military exercises with the Russian army, despite being a member of the Quad (the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States), and I often hear the opinion that “We don’t know which side they’re on—the West or Russia.” From my perspective, that question is nonsense. India is simply India, and a major global power in its own right. It is concerned with its own national interests. There is nothing else to rely on.

Kawashima: You’re right. In another example, the new government of the Philippines is said to be pro-American, but it stems from the context of domestic politics. Foreign media and other media report on this in the context of the US-China conflict, so they are only concerned with pro-American and anti-China stories. The reality is not so simple. The government is working based on domestic politics and regional logic. I hope that research on the diplomacy of not only the Philippines, but also other countries such as Indonesia and India, will proceed based on this kind of internal, regional logic. What is the situation in Africa?

Endo: With regard to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kenyan Ambassador Martin Kimani’s speech at the UN Security Council Emergency Meeting on Ukraine on February 21, 2022—directly before the Russian invasion—attracted attention. He strongly condemned Russia, expressing the view that Russia’s recognition of the independence of the two eastern states of Ukraine against the backdrop of military power reflects the painful history of Africa, and is completely unjustifiable. At the same time, he emphasized that African countries had accepted the national borders drawn by the Western great powers and have been working towards future-oriented and stable relationships. It was a great speech that impressed many people around the world.

On the other hand, at the UN General Assembly held after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there were two resolutions of condemnation against Russia in March and a resolution in April to expel Russia from the Human Rights Council (HRC). However, when it came to voting time, many African countries disagreed, abstained, or indicated their intention not to vote, particularly on the HRC issue. The deep relationship between various African countries and Russia is often pointed out, but both the speech by the Kenyan Ambassador and the results of the UN vote can be said to be in accordance with African regional logic. Russian aggression against Ukraine cannot be forgiven. On the other hand, for example, an area of East Africa—called the Horn of Africa—is currently suffering from severe drought, and he disruption of food supplies from Russia and Ukraine has led to famine, primarily in Somalia. As the term “famine” is also being used at the UN, a situation has arisen in which lives are being lost, and emergency assistance from the international community is anticipated. Without recognizing such realities, it may be difficult to understand Africa’s response [to the Russian issue].

Nakao: One thing I would like to add about the South’s response to the UN resolutions is that it shows that there is dissatisfaction and distrust of Western double standards and deceptiveness. When I spoke with a minister from the Philippines, he said that Russia’s behavior is completely indefensible, but that the United States also had a history of suppressing and killing members of the Philippine Independence Movement. European countries did not recognize the independence of colonies even after World War II, and a lot of blood was shed in wars of independence. Vietnam, Indonesia, Algeria… The list goes on. Those memories are still very much alive, in both Asia and Africa. There is deep-rooted suspicion of Western “justice.” They feel that the actions of Russia are terrible, but looking back, the Western powers were not that great either. Those sentiments are understandable.

Kawashima: The shared experiences of colonial rule, which may be called the “memories of the South,” have created an instinctive wariness of the West’s one-sided ideas of justice.

Nakao: There is a similar image of democracy. When it comes down to it, election-based democracy is ultimately “domination by the majority.” However, in many countries with ethnic minorities and religious conflicts, domination by the majority can often turn into the suppression of minorities.

Kawashima: There is no shortage of such examples, such as the attitude of the Bamar (Burmese) people towards other ethnic groups in Myanmar.

Nakao: Democracy and elections are important, but it is not always possible to put Western standards and methods into practice straightforwardly in Asian and African countries, which have different histories and circumstances. The West, too, was originally run by monarchies and restricted elections, and democracy was not based on elections with voting rights for all citizens from the initial stages of its development.

Kawashima: There is an opening there that China can use. Of course, Chinese justice is also questionable.

Nakao: Asian countries are opposed to China’s hegemonic behavior. They don’t just think what China says is right. However, there is also an element of a shared sense of discomfort with Western deceptiveness with China, and it should be taken into account that there is a basis for a kind of sympathy to take root there.

Kawashima: China intends to use “memories of the South” as a foothold to appeal to other countries about its differences from developed countries and draw in members of the Global South. Similarly, its logic in standing up to Europe and the United States emphasizes maintaining its sovereignty and national borders. How do African countries regard this?

Endo: Sovereign equality, non-interference in internal affairs, and territorial integrity have been principles of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) since its establishment in 1963, and are shared by many African countries. This does not mean that they simply go along with China’s assertions, and there is also a critical perspective on the way in which they are put into practice, as I mentioned earlier in the section on development aid.

The philosophy and message required in Japanese diplomacy

Kawashima: Finally, I would like to hear your opinions about the role that Japanese diplomacy should play in relation to the Global South and its increasing presence.

Nakao: Japan should look for an approach that matches its current economic power. In the past, Japan helped to develop infrastructure in Asian countries through large-scale ODA and showed a growth model for their industries. However, while that model has been shared around the world, Japan itself has been left behind in terms of strong growth, and neither its economic power nor its investments and aid to developing countries can match China’s. In this situation, it is impossible for Japan to be ambitious about uniting Asia or raising up Africa, and in reality, there is no need to compete with China in quantitative terms.

Since the Meiji period, Japan has succeeded on its own in the democratization of politics, such as the establishment of a parliament and universal voting rights for its citizens, and economic development based on market functions. This process involved not only importing systems from Europe and the United States, but also devising ways to establish them in Japan by adjusting them to fit in with the Japanese context. This experience contains many historical and cultural elements.

I think that there is a need to maintain diverse nuances in the economic and cultural spheres and engage with other countries in these regions with a flexible attitude, while at the same time ensuring the Japan-US Alliance for security purposes, but without falling into the binary mentality of democracy or tyranny.

Kawashima: As far as China is concerned, if Japan becomes Western-oriented, it will be easier to handle. On the other hand, if Japan adopts a flexible stance of involving itself with Asia rather than focusing solely on the West, then it will present problems for China. What is the African perspective? In August 2022, the eighth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD8) was held in Tunisia.

Endo: Compared with the time of the first TICAD in 1993, the way in which Japan regards the African continent has shifted significantly—from a target for development aid to a place for investment and business. At TICAD6, which was held in Nairobi (Kenya) in 2016, members of the Japanese business community traveled to the site for business negotiations, and the total number of participants exceeded 10,000. By comparison, TICAD8 was quite small. In fact, Japanese companies’ investment in Africa peaked in 2013 and has since been in decline, and things are not progressing as expected.

The day after TICAD8 ended, the Yomiuri shimbun newspaper published a review by a Kenyan researcher stating that he could not see the strategic nature of TICAD. The Tunis Declaration (TICAD8) contains so many items, but what is the point of it? Prime Minister Kishida announced at the beginning of the conference that Japan would invest 30 billion dollars, but he has not conveyed anything of what he wants to do with it. There may be a strong desire to do something “for Africa”—but I think it’s time to abandon that way of thinking. What is the purpose of Japan, with its limited economic power, being involved in African development? One of the shadow agendas of Japan’s African diplomacy is based on the request for Japanese cooperation with UN reform. It is necessary to properly clarify this, and the aims of Japan’s African diplomacy.

Kawashima: The fact that Japan is not properly conveying what it wants to do is an important point. It is a major prerequisite that we do not impose the binary opposition-based worldview of “the United States or China,” or question their allegiance and force them to choose sides. At the same time, we must strive to understand the perceptions and mindsets of the Global South while avoiding the intention of simply trying to do things “for them.” I think this is the basic policy line. But this alone is not enough. We have to send a clear message, based on Japanese philosophy.

For Japan, the Global South is not simply a political “meadow” to graze in and secure their interests, but simply being close and understanding each other does not make for proactive diplomacy. It will be a new arena and challenge for Japanese diplomacy.

Translated from “Tokushu Gurobaru Sausu kara mita Sekai: Naze ima Gurobaru Sausu wo ronjirunoka (Special Feature “The World According to the Global South”: Why Should We Discuss the Global South Now?),” Gaiko (Diplomacy), Vol. 75 Sept./Oct. 2022, pp. 6-17. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [November 2022]

Keywords

- Endo Mitsugi

- University of Tokyo

- Nakao Takehiko

- Mizuho Research and Technologies

- Asian Development Bank (ADB)

- Kawashima Shin

- Global South

- Europe

- United States

- China

- Russia

- Asia

- ASEAN

- Africa

- emerging countries

- developing countries

- development

- COVID-19

- Ukraine

- international politics

- democracy

- democratization

- civil liberties

- market economy

- aid

- famine

- ODA

- UN

- double standards

- “memories of the South”

- Japanese diplomacy

- TICAD