China in Xi’s third term: Reconciliation of interests still extremely difficult under a de facto personal dictatorship

The photo is the “holy land” of the Chinese revolution in Yan’an City, Shaanxi Province, China. All seven members of the Standing Committee visited here on October 27. It was a performance to emphasize the unity of the members. The authority of Xi Jinping was “strengthened within a political structure that retains the form of a collective leadership system,” points out the author.

Eto Naoko, Professor, Gakushuin University

Key points

- Formal continuation of collective leadership as a means of consolidating the power structure

- Attempt to shift the legitimacy of the CCP to the manifestation of socialism

- Need for Japan to share legally enforceable international rules with China

Prof. Eto Naoko

The 20th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) concluded on October 22, announcing its policies and appointments to the Central Commission. The following day, on the 23rd, with the new leadership inaugurated at the 1st plenum of the 20th CCP Central Committee, the way was paved for General Secretary Xi Jinping’s long-term government as he was reappointed for a third term.

This marked the end of the “system-based transfer of power” mechanism, which had been emphasized as a lesson of the Mao Zedong administration period that had brought major disruptions and setbacks.

The four new members of the Politburo Standing Committee are all close associates of General Secretary Xi, while a majority of the 24 top officials who make up the members of the Central Politburo of the CCP also have personal ties to Xi, belonging to the so-called “Xi faction.” Moreover, with the resignation of political leaders from Xi Jinping’s generation, such as Li Keqiang and Wang Yang, there is no longer anyone in the new leadership who can disagree with Xi. Overall, it can be said that Xi’s rule is approaching a de facto personal dictatorship.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that the slogan “Two Establishments,” which makes Xi’s authority absolute and was repeatedly mentioned at the Party Congress, was not included in the amendment to the CCP Constitution adopted on the 22nd. Instead, the Constitution came to include the slogan “Two Safeguards,” meaning loyalty to Xi and the Central Committee.

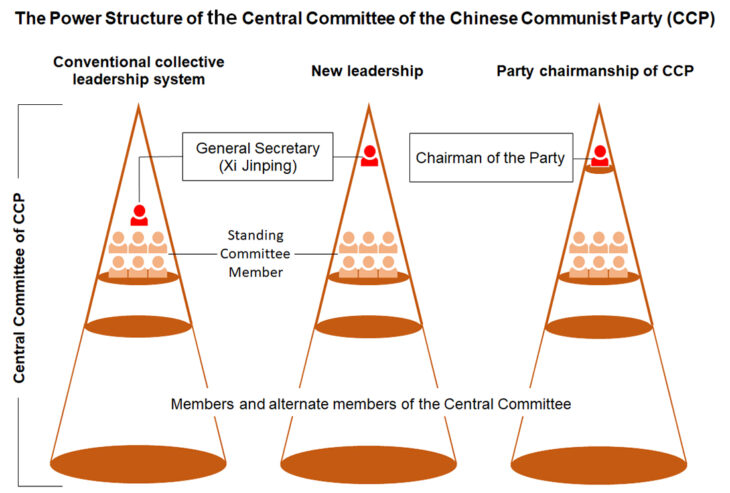

The main difference between the “Two Establishments” and the “Two Safeguards” is whether the Central Committee is explicitly stated to be the governing entity. In other words, the inclusion of only the “Two Safeguards” in the Constitution meant a retention of the rhetoric of a “collective leadership system by the Central Committee.” Just like the non-reinstatement of the position of Chairman of the Central Committee of the CCP (Chairman of the Party), which was often discussed before the Party Congress, and the decision not to use terms that would increase the authority of Xi as an individual, such as “Xi Jinping Thought” and “People’s Lingxiu (Leader),” in the Constitution, this marked an avoidance of identifying Xi Jinping as the governing subject.

However, this does not necessarily mean that Xi Jinping’s authority has declined. On the 27th, after the Party Congress, all seven members of the Standing Committee visited Yan’an City, Shaanxi Province, which is considered a “holy land” of the Chinese revolution, in a performance that not only signified a return to the original intention of the “Yan’an Spirit” overcoming a period of hardship but also emphasized the unity of the Standing Committee members. The authority of Xi Jinping, who has always been standing at the center, is thought to have been rather boosted indirectly by increasing the importance of the unified Central Committee. In other words, individual authority was strengthened within a political structure that retains the form of a collective leadership system.

Why did the centralization of power take this form? The fact that there was deep rooted opposition within the CCP to a structure directly linked to a “personality cult” is doubtless a contributing factor. Concerns about the overconcentration of power were voiced in various quarters and Xi’s leadership which professes party unity presumably had to take heed.

But at the same time, this formal continuation of collective leadership may have been a way to eliminate the political leaders of the non-Xi Jinping faction. Xi Jinping, who reported to the Party Congress at the opening ceremony on the 16th, said that the five years since the 19th National Congress have been “truly momentous and extraordinary,” and that there had been “external intimidation, restraint, blockades, and extreme pressure.” Expressing a sense of crisis about national security in a severe international situation, he asserted that “we will stay closely rallied around the Party Central Committee,” very much indicative of a desire for strong leadership and a functional Party management team.

For the third term, Xi Jinping was likely justifying the appointment of persons close to him under the banner of the “Party’s solidarity and unity” with this understanding of the situation.

So, where is the legitimacy of the Xi Jinping regime to be found? What emerges from the Party Congress discussions is the image of a leader with “red genes” who will complete the building of the socialist country. In his report to the Party Congress, “the Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” which is written bearing his name in the National Constitution, is explained to mean “a new breakthrough in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context and the needs of our times” and using “this new theory to arm ourselves intellectually.”

“Adapting Marxism to the Chinese context” means to adapt the theories of socialism to China’s national circumstances and traditional culture, a concept proclaimed by the CCP in the 1930s and that later culminated in Mao Zedong Thought. In other words, Xi Jinping is framed as a political leader who develops Marxism according to the changing times based on Mao Zedong Thought and who successfully builds “China into a modern socialist superpower” by 2049.

This is an attempt to shift the legitimacy of the CCP, which has previously relied on historical perceptions (past achievements) and economic development (present achievements), to the manifestation of socialism (future achievements). In fact, Xi’s leadership’s goal of “common prosperity for all” means correcting disparities and transitioning to a society in which everyone prospers through the redistribution of wealth and is seen as a departure from the reform and opening-up policy which prioritized economic development.

That said, partly due to the aging of society and the effects of stringent COVID measures, conditions are such that the whole pie is not going to get any bigger and the redistribution of wealth will necessitate smaller slices for some. It is extremely difficult for the CCP, which has grown to incorporate various vested interests and more than 96 million members, to coordinate interests without incurring any dissatisfaction. If Xi Jinping’s leadership enforces a redistribution of wealth under the socialist slogan of “common prosperity for all,” that will probably reduce the cohesive force of the CCP. Above all, property market and tax system reforms, which have important implications for China’s economic structure, will be extremely difficult. To put it another way, steering the country in the direction of socialism out of a desire to show strong leadership could ironically undermine the CCP’s cohesion.

A key strategy for increasing the cohesion of Xi and the CCP will be to use socialist ideology to sway public opinion. Ideological education was noticeably stepped up during the second term of the XI administration and, since 2021, studying Xi’s political thought has become an essential part of every curriculum from elementary school through to graduate school. What is more, the latest report to the Party Congress also clearly specified the policy of “developing and institutionalizing regular activities to foster ideals and convictions” and enhancement of “youth-related information campaigns.”

If the “correctness” of socialist ideology can permeate mainly among young people, the values of Chinese society will fundamentally change in the medium to long term.

How should Japan coexist with a China whose very nature as a state is changing under the Xi Jinping regime?

The areas to focus on now the Party Congress is over are determination of Xi’s leadership’s political line and the United States’ escalation of strategic competition under this situation. In its National Security Strategy announced on October 12, 2022, the Biden administration declared its intention to “outmaneuver our geopolitical competitors.” Similarly, in various discussions I joined in the United States in early November, there was general consensus that China would not be allowed to become a leading high-tech power. Japan must prepare quickly for the move toward decoupling stemming from geo-economic rivalry.

At the center of US-China tensions is the Taiwan issue. In response to large-scale military exercises conducted by the People’s Liberation Army in August, the US is considering ways to deter China, including increasing its military support for Taiwan.

Meanwhile, the report to the 20th Party Congress indicated China’s understanding of the situation, saying that China had carried out “major struggles” against “separatist activities aimed at “Taiwan independence” and gross provocations of external interference in Taiwan affairs.” Although the chances of a Taiwan invasion in the next few years are slim, there will no doubt be increasing military tension in the run-up to the Taiwanese Presidential election in 2024.

To prevent a Taiwan contingency, Japan needs to share a common crisis awareness with China through strategic communication whilst seeking to strengthen defense capabilities. At the same time, it is in the interests of both Japan and China to share legally enforceable international rules and increase the predictability of each other’s actions. Realistic diplomacy that works to build relationships based on rules is vital.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 10 November 2022 under the title, “3-ki me, Shu Seiken no Chugoku (II): Kojin dokusai mo rigaichosei wa shinan (China in Xi’s third term: Reconciliation of interests still extremely difficult under a de facto personal dictatorship).” The Nikkei, 10 November 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Eto Naoko

- Gakushuin University

- Xi Jinping

- collective leadership

- personal dictatorship

- 20th Party Congress

- Chinese Communist Party

- CCP

- transfer of power

- Xi faction

- Two Establishments

- Two Safeguards

- centralization

- Marxism

- socialist ideology

- ideological education

- US-China

- decoupling

- Japan

- Taiwan

- diplomacy