Evaluation of Kishida’s diplomacy and challenges for the next generation

On May 21, 2023, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who visited Japan to attend the G7 Hiroshima Summit, laid flowers

at the memorial at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park together with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio.

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Looking back on the three years of the Kishida Fumio administration, there have been major diplomatic achievements, including support for Ukraine, the three national security documents, the G7 Hiroshima Summit and Japan-Korea relations. As the new prime minister moves to the next stage, he must have a strategy for the new era where diplomacy and economics intersect.

Editor’s note: This article was written before the LDP presidential election vote on September 27 and first published in Japanese in the Sept./Oct. 2024 issue of Gaiko (Diplomacy).

On August 14, 2024, Prime Minister Kishida announced his intention not to run in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) presidential election next month, and his nearly three-year tenure as president of the LDP and prime minister is coming to an end. The reason for Kishida’s resignation is likely to be his inability to withstand growing criticism over domestic issues, mainly related to the economic situation and the LDP’s response to political funding issues. On the other hand, the foreign and security policies of the Kishida administration have been highly praised by both international and domestic experts. In fact, there are several achievements that deserve praise, such as the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the revision of the three security documents, the hosting of the G7 summit in Hiroshima, and the improvement of Japan-South Korea relations. Kishida’s resignation may be indicative of a common feature of current democracies in that foreign policy leadership does not necessarily translate into domestic acclaim. In this article, I will summarize the achievements and challenges of the Kishida administration’s foreign and security policy, consider why such a gap in assessment exists, and offer clues to the challenges facing the new administration.

The invasion of Ukraine that defined Japan’s diplomacy

Looking back to around October 2021, when the Kishida administration began, the world was still busy responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, and Japan was not in an environment to actively pursue diplomacy. This situation changed dramatically on February 24, 2022, when Russia launched a large-scale military invasion of Ukraine. As a result, the Kishida administration’s diplomacy was consistently defined by its response to this situation.

The G7 served as Japan’s main diplomatic channel regarding the situation in Ukraine. In 2022 alone, the G7 held six summits, including online summits, and eleven foreign ministers’ meetings, attempting to lead the international community’s efforts. The Japanese government was also quick to respond, joining other G7 members in supporting Ukraine and imposing sanctions on Russia. The sanctions against Russia, although their content varied from country to country, included financial sanctions (exclusion from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication [SWIFT] and freezing of assets of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation), export restrictions to Russia, import restrictions from Russia, withdrawal of most-favored-nation status, freezing of assets of President Putin and oligarchs, and other measures, and except for restrictions on energy imports, they were almost in step with Europe and the United States. It can be said that Japan led South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and other countries in the Asia-Pacific region that joined the sanctions against Russia. In March 2022, Russia took countermeasures by designating 48 countries and regions that joined the sanctions as “unfriendly countries and regions,” causing a chill in Japan-Russia relations.

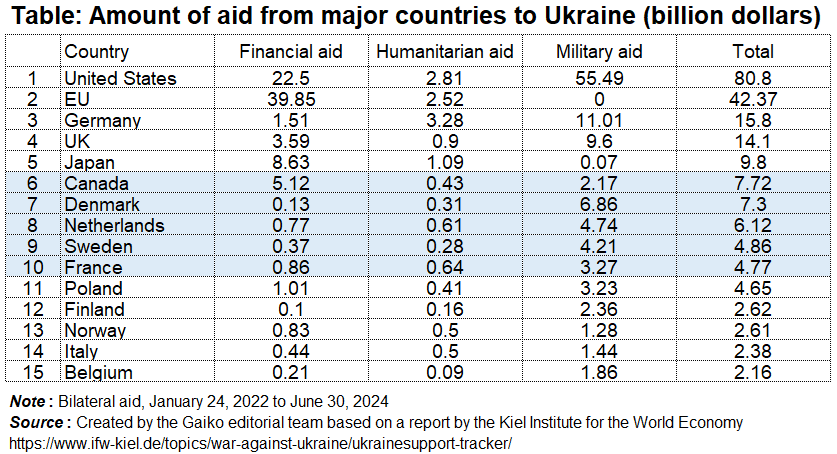

As of June 2024, the international community has donated a total of $210.8 billion to Ukraine, led by the United States with $80 billion (military, humanitarian, and financial aid). Japan has donated $9 billion, making it the fifth largest donor after the United States, the European Union (EU), Germany, and the United Kingdom. The EU and Japan specialize in financial and humanitarian aid (see table).

In addition to supporting and sanctioning the warring parties, Japan has also been active in communicating the injustice of Russia’s actions to the international community, especially to countries in East Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Looking around the world, there are few countries that actively tolerate Russian aggression, but the strength of opposition and criticism is not uniform. On March 2, 2022, in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, the UN General Assembly resolution, co-sponsored by more than 90 countries, including Japan, demanding that the Russian Federation immediately cease its illegal use of force in Ukraine and withdraw all its forces, was adopted by an overwhelming majority of 141 countries. However, 35 countries, including China and India, abstained (12 did not vote, 5 voted against), and the situation has not changed in subsequent General Assembly resolutions in which a certain number of countries abstain. Moreover, the number of countries actively working to impose sanctions on Russia and support Ukraine is limited. Many emerging and developing countries, while critical of Russia’s invasion, continued to maintain “realistic” relations with Russia and China in accordance with their national interests, prioritizing their suffering from rising food and energy prices and climate change. As the invasion of Ukraine dragged on, the stance of these emerging and developing countries grew in importance. Around this time, the term “Global South” became popular worldwide (Gaiko also ran a special feature on “The World According to the Global South” in its 75th issue [September/October 2022]). In response to this situation, Japan has become more proactive than ever in its role as a bridge between Western countries and the Global South, inviting countries such as Indonesia, India, and Brazil, which will chair the G20 from 2022, to the G7 Hiroshima Summit in 2023.

Three documents indicate a major shift in security policy

In the context of responding to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one of the most important achievements of the Kishida administration is the revision of the three security documents (the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program) in December 2022. In terms of form, the National Security Strategy, which was first formulated in December 2013 under the second Abe Shinzo administration, has been revised along with the National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) and the Mid-term Defense Buildup Program in light of changes in the international situation over the past decade, but the changes made are quite significant and substantive.

The foreign and security policies of the Kishida administration basically follow the lines of the second Abe administration, but the impact of the shift in relations with Russia due to the situation in Ukraine was significant. As Prime Minister Kishida has repeatedly stated, “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow,” Russia’s armed invasion and protracted fighting, as well as its growing nuclear threat, have made the risk of military conflict in the Indo-Pacific and East Asia more apparent than ever. At the same time, sanctions against Russia have strengthened security ties with Europe, creating momentum for building a defense posture.

This shift is also reflected in the explicit positioning of the National Security Strategy as the highest level security policy document and the clarification of its relationship to the National Defense Strategy and Defense Buildup Program, which have been renamed from the previous National Defense Program Outline and Mid-Term Defense Program. The National Security Strategy outlines policies based on a definition of national interest and an understanding of the international situation, but what is important is that it was formulated primarily by the National Security Council (NSC) and calls for a government-wide effort that includes not only the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense, but also economic ministries and agencies. It is a strategic document that addresses security issues as a whole-of-government effort in areas where the need has long been recognized but progress has not been made, such as strengthening cybersecurity.

It is also important to note that the defense spending level for fiscal year 2027 is set at 2% of gross domestic product (GDP), which is on par with the goal of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries. However, this is positioned as defense spending in a broad sense, including research and development and infrastructure development, in addition to defense spending as the budget of the Ministry of Defense. This reflects the fact that national security is seen not only as a matter of expanding defense equipment, but also as a matter of overall national strength, including the economy and technology. Of course, the defense budget in the narrower sense has also been significantly increased, and in addition to the construction of an integrated missile defense system, including the development of stand-off missiles, active contributions have been made to areas that have not received adequate budgetary allocations in the past, such as the expansion of ammunition and hardening of facilities that are essential for strengthening war-fighting capabilities. This can be said to be a landmark shift in Japan’s postwar security and defense policy.

The G7 Hiroshima Summit had clear goals

The culmination of Kishida’s diplomacy was the G7 Hiroshima Summit in May 2023. Held in East Asia a little more than a year after the invasion of Ukraine, and with the A-bombed city of Hiroshima as its stage, the summit attracted a great deal of international attention, especially because it focused on nuclear disarmament as one of its themes.

The first achievement of the Hiroshima Summit was that the G7 clearly communicated their unified commitment to continued support for Ukraine. This message became even more symbolic with Ukrainian President Zelensky’s surprise visit to Japan. Second, the fact that the summit advocated “de-risking,” with partial competition in mind, rather than “decoupling,” which evokes a complete break with the Chinese economy, is noteworthy as a new approach to achieving economic security and economic resilience. Unlike the Soviet Union during the Cold War, it did not deny China’s presence in the global economy, but expressed a sense of the problem of how to achieve the “small yard, high fence” advocated by the Biden administration.

Third, the “Hiroshima Vision” was announced, which proclaimed efforts for nuclear disarmament, and the participating countries reached a consensus that they would never tolerate the use of nuclear weapons by Russia. Fourth, relations with the Global South were strengthened. The summit was attended by the leaders of eight countries, including Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Korea and Australia. In light of the above, it appears that the overall policy of the G7 Hiroshima Summit was clear and that the intended goals were largely achieved.

Still, the apparent success covered the potential contradiction on the nuclear issue. The agreement to avoid the use of nuclear weapons by Russia was an important achievement, but the fundamental contradiction between Hiroshima’s original wish for nuclear disarmament and abolition and nuclear deterrence as a countermeasure against “changing the status quo by force” by Russia and other countries has become more acute than ever. This contradiction reflects the difference in positions between developed Western countries and some developing countries, and may be consistent with the absence of G7 ambassadors at the Nagasaki Peace Memorial Ceremony this summer. The absence of the ambassadors was primarily a sign of the Western countries’ continued strong support for Israel in the Gaza conflict that began last year, and was also a protest against the policy of treating Israel and Russia on an equal footing at the ceremony. However, in terms of the “contradiction” mentioned earlier, it also reflects the conflict between Japan’s position, which emphasizes maintaining the status quo through force, including nuclear deterrence, and Japan’s pacifist sentiment in its desire to abolish nuclear weapons.

Promoting stronger relations with friendly and like-minded nations

The third achievement of Kishida’s diplomacy is the strengthening of relations with friendly and like-minded countries. The improvement in Japan-Korea relations is particularly noteworthy. This trend was led by the change in policy toward Japan by the South Korean administration of President Yoon Suk Yeol, but Prime Minister Kishida seized the opportunity to conduct shuttle diplomacy and establish a close personal relationship, which greatly advanced Japan-Korea relations. This also promoted cooperation among Japan, the United States and South Korea. It is still fresh in our minds that a summit was held at Camp David in the United States in August 2023, and the joint statement, “The Spirit of Camp David,” heralded the beginning of a new era of Japan-US-ROK partnership.

Prime Minister Kishida (right), President Biden and President Yoon attend the Japan-US-ROK summit held at Camp David on

August 18, 2023.

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Furthermore, with Australia, the “Japan-Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation” was announced in 2022, and the Japan-Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement was concluded in 2023. With the Philippines, the Japan-US-Philippines Summit was held in Washington in April 2024. In July, the Japan-Philippines Reciprocal Access Agreement was concluded. As for Europe, Japan has participated in the Partner Countries’ Session in the NATO Summit for three consecutive years starting in 2022, and agreed on a framework for jointly developing a next-generation fighter aircraft with the United Kingdom and Italy from last year to 2024. As the security environment in East Asia becomes increasingly challenging, strengthening cooperation with friendly and like-minded countries is an issue that the new administration must continue to actively address.

The revision of the Development Cooperation Charter in June 2023 should also be mentioned. The new guidelines position “human security” as a guiding principle, and with the concept of a free and open Indo-Pacific in mind, they advocate the strategic use of ODA in a contemporary manner, such as the introduction of an “offer-type” approach involving various actors. For Japan, ODA will continue to be a useful diplomatic tool, and at the same time, it will be important as an approach to the Global South that is different from that of Europe, the United States, and China.

In this way, it can be said that there are sufficient reasons for Kishida’s diplomacy to be highly regarded internationally.

The remaining agenda—dialogue with China

The most important issue that Kishida’s diplomacy has yet to address is dialogue with China. Since Prime Minister Abe visited Beijing and met with President Xi Jinping in 2018, there has been no summit in the form of a bilateral visit. In 2020, the Abe administration was preparing to invite Xi as a state guest, but this did not materialize due to the impact of COVID-19. Despite rising tensions with China, Western countries continue to hold dialogues with China at the summit and ministerial levels, while Japan seems to have been somewhat left behind.

While the Kishida administration’s China policy has been enthusiastic about improving deterrence, the other pillar of diplomacy, dialogue and cooperation, has not necessarily progressed smoothly. There is probably more than one reason for this, but it is also true that there is no momentum for dialogue on the Japanese side. In the past, when governments were unable to move forward, politicians and businessmen who were familiar with China sometimes acted as mediators. Over time, however, the aging of the people involved and the growing burden of being labeled “pro-China” have narrowed these channels. Nevertheless, the importance of dialogue with the neighboring major power and the risk of weakening relations through the absence of dialogue are undeniable. Communication between leaders is particularly important with countries where the nature of personal dictatorship is becoming more pronounced. It is unclear whether the change of prime minister will be an opportunity, but efforts will be needed to advance summit diplomacy while explaining and persuading the public.

In this regard, the lack of public explanation and persuasion may have been a weakness of Kishida’s diplomacy. This was also seen in the revision of the three security documents. It seems that many people recognized the importance of strengthening the security system in the abstract, but opportunities for serious debate on concrete contingencies have been seriously missing in the Diet or in the media. This lack of explanation may have been connected with the lack of the discussion on funding for the defense spending. The public is expected to resist tax increases, but defense spending is a permanent expense and it is natural that stable funding is needed for the future. The government should have made efforts to explain and persuade the ruling party and the public, but the Kishida administration postponed the discussion of tax increases in the fiscal 2024 budget and covered the increase in defense spending by resorting to a stopgap measure by using the surplus funds from the fiscal accounts. This issue will be a challenge for future administrations.

An era in which diplomacy and the economy are linked

The new administration’s diplomacy will likely begin in earnest after the results of the US presidential election are announced. However, regardless of who wins, the US’s political division and inward-looking tendency will continue, and the “US-led international order” as it was in the past will not be a given. Furthermore, even if the new US administration tries to focus on the Indo-Pacific region with competition with China in mind, it will be impossible for the US to completely withdraw from issues in other regions. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in Europe and the Gaza conflict in the Middle East have shown the need for US involvement. Japan must maintain the US’s presence in the Indo-Pacific region while strengthening its relations with friendly and like-minded countries in the region and Europe in order to maintain the international order.

In this regard, as stated in the National Security Strategy, Japan should conceive of its security by integrating elements such as economy, technology, and intelligence in addition to diplomacy and defense in the narrow sense, and this could also become a strategy for restoring Japan’s national strength.

Future leaders will need to consider and develop measures to strengthen Japan’s economic, technological, and intelligence power. There will be an increasing number of areas where security and the economy intersect, such as the development of artificial intelligence (AI), building economic security and resilience, global environmental issues, energy issues, and responding to green transformation (GX). However, given the limitations of Japan’s human, material, and financial means, resources cannot be allocated without planning or limitlessly simply because some policy appears important. In the future, it will be necessary to make strategic investments after carefully considering how much human, material, and financial resources to allocate to each area. In addition, leaders will need to explain the impact of such investments to the public and gain their understanding.

In this regard, although the Cabinet Office has established the NSC as the control tower for diplomacy and national security, and the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy as the control tower for economic and fiscal policy, given the increasing need to fathom the national power comprehensively, they seem to lack the function of comprehensively considering the overall cultivation of national strength and resilience in peacetime as well as in times of emergency. At a time when the world situation is in a state of tension, we need deep strategic insight that can gather the wisdom of the general public, and we must avoid wasting resources by being swayed by a superficial sense of urgency. The resignation of the Kishida administration, which had achieved many diplomatic successes, shows the need for leadership with a broad perspective that can oversee diplomacy, domestic affairs and the economy.

Translated from “Kishida Gaiko no Hyoka to Jisedai eno Kadai (Evaluation of Kishida’s diplomacy and challenges for the next generation),” Gaiko (Diplomacy), Vol. 87 Sept./Oct. 2024, pp. 6-13. (Courtesy of Toshi Shuppan) [December 2024]