The Future of Development Cooperation: Preventing Problems Rather than Solving Them

Dr. Nakamura Tetsu (1946–2019) delivered a speech at the ceremony for the completion of Sheiwa Intake and Canal on March

15, 2008.

Photo: Courtesy of PMS (Peace Japan Medical Services) & Peshawar-kai

Key Points:

- Aid based on the “request” of the recipient country needs to be reexamined.

- We must build trust on the ground. Dr. Nakamura Tetsu can be a role model.

- We should shift to identifying problems together with local people.

How has Official Development Assistance (ODA) identified problems and formulated projects in the past? The answer to this question will be an important starting point for predicting the future of ODA.

After WW2, Japan came up with the idea of including economic reconstruction in postwar reparations and economic cooperation. Economic cooperation eventually became ODA, and the purpose of maintaining the US-led free economic zone was added. The scope of activities also expanded beyond economic infrastructure such as roads and ports to include health, education, the environment, and peace-building. In recent years, there has been interest in the role of ODA in peace and security.

Although the scope of ODA has expanded, the method of project formation has remained almost unchanged. Japan has adopted a method of project formation by prioritizing requests from recipient governments. This yosei-shugi (the “request-based” principle) emphasizes the promotion of self-help efforts by recipient governments, in contrast to major Western donor countries that emphasize human rights, freedom and democracy. The attitude of respecting the development plans of recipient countries has also been useful in building relationships with developing country governments in a way that differs from that of the West.

In the 1980s, the Japanese method, in which corporations play a major role, was criticized by Western countries as “commercialistic and unprincipled.” Criticism also grew within Japan, especially of aid emphasizing hard infrastructure. When politicians in the recipient country are involved in “requests,” large-scale infrastructure and new technologies are given priority, and the environment and the rights of local residents are sometimes put on the back burner.

◆◆◆

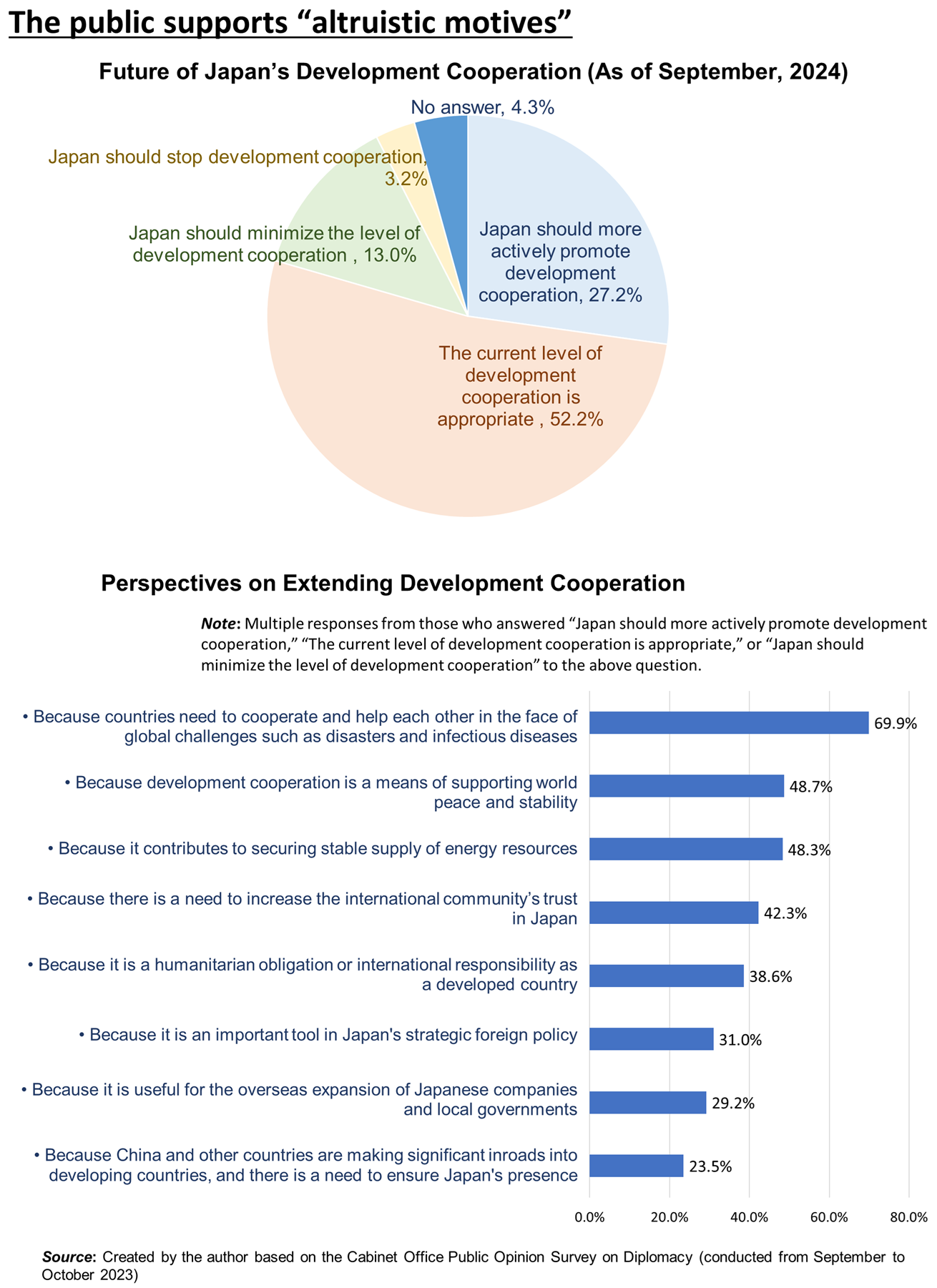

In the 21st century, the size of Japan’s ODA budget shrank, and former recipient countries, including China, gradually became donor countries. It was also during this period that the Japanese government began to put “national interests” first. In this context, the results of domestic opinion polls show an interesting trend. The reason why people support ODA is that they emphasize the altruistic aspects of aid, not because aid serves the national interests. For example, in the results of the most recent survey conducted in September 2023, the percentage of people who cited “mutual assistance among countries” and “world peace and stability” as reasons why development cooperation is necessary exceeded responses such as “important for Japan’s diplomacy” and “overseas expansion of Japanese companies” (see chart).

In this regard, it is meaningful to look back at the achievements of the late Dr. Nakamura Tetsu (1946–2019), who worked at the grassroots level in Afghanistan and Pakistan for 35 years while keeping some distance from ODA. Dr. Nakamura expanded his activities from treating leprosy patients to digging wells to secure water sources, with his motto “We choose not to go to places where everyone is willing to go, but rather to places where help is desperately needed and no one dares to go.” He was a doctor who eventually achieved the feat of turning the desert into green land through irrigation, and was shot dead in the area in December 2019.

The core aim of Dr. Nakamura’s activities was building trust with the local people. In the film Lighting a Light of Hope in the Wilderness, which documents part of this project, there is a scene where the villagers ask Dr. Nakamura, who is trying to persuade them to build a hospital, “Don’t you help us on a whim and then leave us right away?” Dr. Nakamura replies, “Even if I die one day, I am determined to keep this clinic going.”

Dr. Nakamura went beyond his specialty as a doctor and personally went into the field, using his local connections and blood ties to expand his activities to include flood control and agriculture. This is in contrast to typical ODA projects, which are limited to one sector over a five-year period and are supervised by Japanese personnel.

His choice of technology was also unique. Dr. Nakamura learned the local language and emphasized technology that the people could maintain and manage themselves while understanding their culture. A symbolic example of this is the irrigation canal, modeled after Japan’s Edo-period “Yamada Weir.” In the Edo period (1603–1867), when there was no choice but to rely on local resources and labor, Dr. Nakamura saw an example of technology that would be useful to developing countries today.

The greatest lesson he left us is to invest time in finding a solution that does not create problems, rather than trying to solve problems one at a time. The digging of wells and irrigation that made Dr. Nakamura famous, for example, was intended to prevent diseases caused by unsanitary water and to restore agriculture. We must remember, however, that it took him more than 10 years to get there.

His approach of going back to the roots of the problem also has great implications for world peace. Dr. Nakamura focused on agricultural assistance and flood control to maintain normal life and prevent the creation of refugees, rather than on reconstruction after peace has been broken.

◆◆◆

If I were to draw lessons for ODA from Dr. Nakamura’s experience, I would highlight the following three points.

The first is to arouse the interest of the Japanese people. ODA funded by taxes becomes stronger and stable when it has the broader public support. Dr. Nakamura tried to inform the public about what was happening on the ground by writing articles in the newsletter of the Peshawar-kai (society) based in Fukuoka City and giving lectures all over Japan. In order to gain widespread public support for ODA, we need reports that help the young generation identify role models following in the footsteps of such figures as the late Ogata Sadako[1] (1927–2019) and Dr. Nakamura.

The second is to enable aid recipients to rely on intermediate groups that are rooted in the local area, such as lineage and professional groups. People live their life by belonging to different groups at the same time. It is important to reach out to local groups such as cooperatives, community organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and to establish a system that can operate on its own even after the project is completed, rather than depending on governmental aid.

Dr. Nakamura found the importance of local ties rooted in each region to be the reason why a total of about 100,000 people enthusiastically participated in the construction of the irrigation canal. ODA should support organizations that are the key to fostering such local ties.

The third is to empower recipients to understand the “problems” that are the target of assistance. To avoid creating unmanageable problems in the region, a deep understanding of the mechanisms that cause problems in the region is necessary. This can be achieved through improvements such as extended staff rotation so that aid workers can stay in a particular region for a longer period of time, increased recruitment of local staff, and encouragement to learn the local language. And above all, we should guide ODA issues to be identified “from below” together with the people of the recipient country through the localization of projects. Up to now, key ODA priorities have been guided by established organizations such as the United Nations and the World Bank. In a world where pleasant-sounding terms such as SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) and good governance are being bandied about, we need to ask, “Whose development issues are these?” In contrast to conventional modernization in search of a convenient and comfortable life, we need to restore a humane life for people facing socio-environmental crises.

Where should we find a landing point between the opposing axes of investment-oriented development for modernization and the grassroots approach for restoring people’s lives? First of all, we must free ourselves from the curse of “problem solving” and devote ourselves to helping to train local communities to have a constitution that does not create problems to begin with. This is the future of development cooperation.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 31 October 2024 under the title, “Kaihatsu Enjo no Yukue (III): Mondaikaiketsu yori Hassei no Yobowo (The Future of Development Assistance: Preventing Problems Rather than Solving Them),” The Nikkei, 31 October 2024. (Courtesy of the author)

[1] Ogata Sadako (1927–2019) was the former United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the former President of JICA. After graduating from University of the Sacred Heart, she earned a master’s degree in International Relations from Georgetown University and Ph.D. from UC Berkeley. She also served as the Special Representative of the Prime Minister of Japan on Reconstruction Assistance to Afghanistan in 2001. https://www.japanpolicyforum.jp/diplomacy/pt2020073115321810555.html

Keywords

- Sato Jin

- University of Tokyo

- official development assistance

- ODA

- future of ODA

- development cooperation

- project formation

- yosei-shugi

- request-based

- mutual assistance

- self-help

- Nakamura Tetsu

- identifying problems

- local ties

- irrigation canal

- Yamada Weir

- Peshawar-kai

- Ogata Sadako