JAPAN PLAYS CATCH-UP TO WIN SATELLITE ORDERS

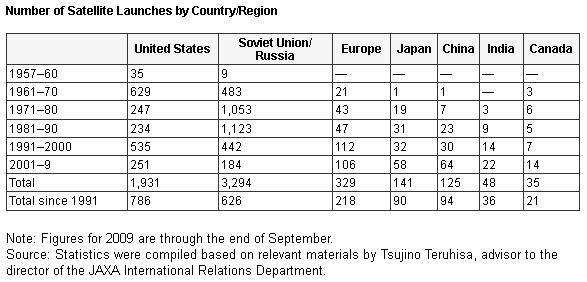

Exactly 40 years ago Japan launched its first satellite. In 1970, after four failed launches, the Ōsumi was successfully sent into orbit, making Japan the fourth country to have its own satellite–after the former Soviet Union, the United States, and France. According to materials published by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), Japan has launched 141 rockets as of 2009, placing it fourth after Russia (3,294, including the Soviet era), the United States (1,931), and the European Space Agency (329). In this sense, Japan can be described as a “satellite superpower.”

In the realm of business, however, Japanese satellite makers lag behind. There are two companies in Japan that manufacture commercial satellites: Mitsubishi Electric and NEC. Yet of the 20 telecommunication satellite models currently in use, 19 were produced outside of Japan. Mitsubishi Electric, which is Japan’s top satellite maker, only received its first overseas order for a commercial satellite (for use in telecommunications) in 2005. This was followed, in 2008, by the company receiving an order from telecommunication companies in Singapore and Taiwan for its ST-2 communications satellite. But no other satellite maker in Japan has received such overseas orders. Not only has Japan failed to catch up to the leaders in space exploration, such as the United States, Europe, and Russia, in this respect, it has not even been able to match China or India.

Struggling to Win Orders

So how did Japan find itself in this situation? Industry sources claim in unison that the culprit in this case was the US-Japan Satellite Procurement Agreement, signed in 1990.

Back in the 1980s, when export-driven growth was earning Japan praise as the world’s “number one” economy, trade friction with the United States intensified in the automobile, semiconductor, and computer industries. Japan gave in partially to the pressure exerted by the United States and signed the US-Japan Satellite Procurement Agreement, which stipulates procurement procedures for satellites. The agreement states that all government satellites for practical applications–apart from those used for research and development purposes–should be subject to open international bidding.

As a result, Japanese manufacturers were subject to intense competition with manufacturers in the United States and Europe that were the leaders in satellite development. Competing in the global market for commercial satellites requires the accumulation of know-how from handling a large number of satellites and the reduction of costs, but Japanese manufacturers found it difficult to garner the amount of experience needed as their overseas counterparts began grabbing orders for practical-use Japanese government satellites, such as the Himawari series of meteorological satellites.

Some telecommunication and other satellites were labeled “engineering test satellites” to place them outside the framework of the US-Japan Satellite Procurement Agreement so that the orders could go to Japanese manufacturers. However, this required the incorporation each time of some new technology for the sake of research and development. That caused a limit in how much repeated launching of the same satellite could increase the level of trust or generate a cumulative effect.

Mitsubishi Electric representatives, looking back, have noted that the company could not match US manufacturers at all, whether in the areas of performance, cost, or lead time, because of the greater level of experience of those rivals. There is even a resentful view within the industry that satellite production was sacrificed to safeguard the automobile and semiconductor industries.

Yet there are some hopeful signs on the horizon. In recent years, Mitsubishi Electric has been able to win orders thanks to the development of its “satellite bus,” which integrates the common components needed for any satellite, such as power supply and communication equipment as well as propulsion engines. With the use of the satellite bus, all that remains is to add the specific devices needed for the purposes of the satellite. This makes it possible to cut costs and greatly reduce lead time. The major overseas satellite manufacturers in fact all have powerful satellite buses. Now that Mitsubishi Electric has finally managed to set foot on the same playing field, it is gradually improving its competitiveness, and last year it won a bid from the Japan Meteorological Agency for the launch of the Himawari 8 and 9.

Last October, at Mitsubishi Electric’s first explanation of its space business for members of the press, Kurihara Noboru, then head of the company’s Electronic Systems Group, enthusiastically spoke of wanting to achieve a twofold increase in sales over the next 10 years, to the level of ¥150 billion, so as to move up from its current position as number eight and join the ranks of the world’s top five.

Japanese Government Backing

The Japanese government has also changed course with regard to backing the private-sector satellite business. The Strategic Headquarters for Space Development, headed by the prime minister, clearly stated in its “Key Measures in the Field of Space” document, released in May 2010, the “aim of achieving a twofold increase in the scale of Japan’s space industry over the next 10 years–to around the level of ¥14 to ¥15 trillion–by expanding the space equipment industry via international competition and broadening the base of the space utilization industry.”

The key policy for this endeavor will be cooperation between the public and private sectors to promote Japanese products in those Asian countries with budding space programs. Maehara Seiji, the cabinet minister in charge of transportation as well as space development, visited Vietnam in May to encourage that country’s introduction of satellites as an integral part of its social infrastructure–alongside nuclear power plants and high-speed rail.

Another effort underway, with an eye to development in Asia, is to spark new demand through the low price of a compact satellite that weighs under 500 kilograms. This ASNARO satellite, developed with support from the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, utilizes the compact NEXTAR satellite bus produced by NEC. The aim is for the satellite to be able, despite its compact size, to discern objects on Earth as small as half a meter in size.

But other leading nations in the space industry also have their sights set on making inroads in countries with budding space industries, knowing that many of the systems first introduced in those countries will end up becoming the mainstay systems. China in particular is likely to be Japan’s main rival in Asia in this competition.

Japan has been a major presence on the scene through hosting the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum and by engaging in activities that have included the provision of satellite data during times of disasters and offering space-related education. China has been participating in the forum, but recently it began its own independent activities by establishing the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization. China has also been actively providing countries in Africa and Latin America with satellite systems, perhaps with an eye to securing natural resources in return.

JAXA has continued its cooperative research efforts, which include a joint project with the space agencies of six countries (including Vietnam and Thailand) to develop a compact Earth-monitoring satellite. Winning satellite orders from developing countries requires not just technology but also providing advice on optimal ways to utilize outer space, fostering technicians, and putting in place a framework to make use of data. This sort of persistent interaction–along with support from government officials for the sales effort and financial backing–will be the key to success.

Translated from “Sekai yon’i no eisei taikoku Nippon, juchū no okure bankai e kōsei,” Ekonomisuto, August 24, 2010, pp. 96-97. (Courtesy of the Mainichi Newspapers) [September 2010]