Can we learn from history, or do we simply repeat history?—Trump’s trade policy from an economics perspective

When similar events occur

Prof. Inoki Takenori

In his book Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crisis, C. P. Kindleberger, the economic historian who analyzed the history of financial crises, adopts quite a gloomy historical perspective on the interactions between economic systems and people. Bubbles occur when mania (hyper-optimism) becomes prevalent in society. However, bubbles will burst at some point, causing panic and, in the end, plunging economic systems into collapse and panic. Have we not been through these processes any number of times in the modern era? Such hyper-optimism suggests a social climate where the prevalent economic behavior is excitable, yet relaxed about reckless borrowing and lending, believing all will be well. The pattern of manias, panics, and crashes applies unchanged to the collapse of the bubble economy in Japan in the late 1980s, the United States at the time of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy ten years ago, the bewilderment in the EU over the whole financial crisis in Greece, as well as other instances.

The first edition of Kindleberger’s book was published in 1978. In the fourth edition (2000), the last one to be revised before his death, Kindleberger states pessimistically that the world does not seem to learn from past mistakes and is unlikely to learn anything in the future.

It is hardly newsworthy to say that similar phenomena are repeated throughout history. However, observing the world economy and the upheavals in international relations of recent years, one is compelled to once again consider whether there is not some deeper truth inherent in the phrases “learning from history” and “repeating history.”

It is hardly surprising that similar events will recur unless humanity changes. However, being steeped in the modern sciences that emphasize reason, we have a tendency to think that the human mind is continually enlightened through education and rational thinking based on the intellect, and that promising technological progress will create a society of unending affluence and stability. In the progressive view of history where reason finds solutions to all problems, a particular period in history is simply the precursor to the next period and has no other value or significance.

Do integration and separation recur?

When reflecting on the world affairs of the past several years, one becomes aware that the move toward integration and convergence, which had been making steady progress, is now in retreat while the tendency for separation and dispersion has again become predominant. In 2016, Britain took the decision to leave the EU following a national referendum while Donald Trump, inaugurated as President of the United States in January 2017, emphasizes an “America First” approach that changed the nation’s course toward policies that highlight protectionism and exclusivism. If we understand civilization as “the will to coexist,” these developments toward separation and dispersion represent a revival of barbarism that is opposed to the progress of civilization.

The concept of civilization requires the power to imagine how human beings can coexist with each other. This point is also evident in the way that the concept of the citizen is linked to civilized society. Citizens are intrinsically discrete individuals who come together for a common advantage while learning to coexist with people who have dissenting views.

A society where there is no dissent and where the homogenous majority has forced itself into a position of strong civil power cannot claim to be a civil society. As José Ortega y Gasset points out in The Revolt of the Masses, it is the true nature of civilization to coexist while acknowledging those who have dissenting views. The concept of barbarism, which is the opposite of civilization, implies a state that is focused solely on combat without any will to coexist. The age of barbarism was a time when humanity was dispersed, a time of rampant separation and antagonism between small communities.

With this perspective in mind, looking back at the past several years of turmoil and moves toward separation and exclusion, there is a growing sense that the pendulum is swinging back from the age of civilization to the age of barbarism. The principle of equality among nations has suffused both trade and diplomacy, which accounts for the diminishing influence of the United Nations and the WTO, as well as the decline in the leadership of the United States on the stage of international politics. In a context where the Trans-Pacific Partnership is becoming less effective, and where numerous existing free trade agreements constitute the core of the world trade systems, we can see how multilateral international trade frameworks with WTO freedoms are changing direction toward separation.

The principle of equality in democracies is separating people, plunging them into individualism where they shut themselves into a private world of self and family, losing interest in the common advantage. A similar trend toward separation is also manifest in the principle of America First, which stands for a turning inward and prioritizing of one’s own country.

Two arguments by Trump

Under these circumstances, the new US President is hammering out a rapid succession of policies that ride the current of separation and dispersion. Trump has shifted the position of the United States toward bilateral negotiating frameworks, withdrawing from one multilateral treaty and agreement after another including the TPP, the Paris Agreement, UNESCO and the nuclear agreement with Iran. Such unilateralism, trade protectionism and exclusionism are incompatible with the forces that move civilizations forward.

Since the presidential election campaign, Trump has continually claimed that the trade deficit with China and Japan takes jobs from the US manufacturing sector. He claims that the most urgent trade policies for the United States are to introduce high tariffs to prevent imports from China, to correct the trade deficit with China, and to restore employment in the US manufacturing sector. At first glance, such a trade policy appears intuitive and obvious, but the logic is flawed when viewed from a macroeconomic perspective.

In a macroeconomic context, a country’s external balance is constrained due to its accounting relationships (identity equation). To finance a country’s private sector investment and the government budget deficit requires an equal amount of private saving and current account balance surplus (net exports of goods and services). In other words, in accounting terms, the constraint is that the share of private sector saving that exceeds investment is always equal to the sum of the budget deficit and the surplus in the current account balance. This fundamental identity equation in the international macroeconomy tells us that the external balance of payments depends on a country’s total saving, investment balance and the budget deficit. If all other conditions are equal, this means that any deficit in the external balance of payments will not be eliminated unless domestic saving exceeds investment.

Seen in this light, it would appear that politicians and policymakers in the United States—a country where economics should be advanced—do not have a well-developed understanding of the macroeconomy. One is also compelled to point out that neither politicians nor citizens have learned much from the past.

To examine Trump’s factual awareness and assertions about trade policies, I would like to consider the issues from two perspectives while keeping the abovementioned points in mind. (1) What degree of truth is there in the assertion that the rapid increase in imports from China has taken jobs from the US manufacturing sector? (2) Is a protectionist trade policy in the face of the worsening external balance of payments the correct (profitable) policy for the United States?[1]

To go directly to the conclusions, where the first point is concerned, the sudden increase in Chinese imports when China joined the WTO—the so-called China shock—led to a decrease in US manufacturing sector employment of just under twenty percent. On the second point, the US (and the world economy) will gain nothing from Trump’s protectionist policies unless the budget deficit and / or the saving and investment structure of the US macroeconomy changes.

(1) To what degree has employment in the US declined due to the Chinese export offensive?

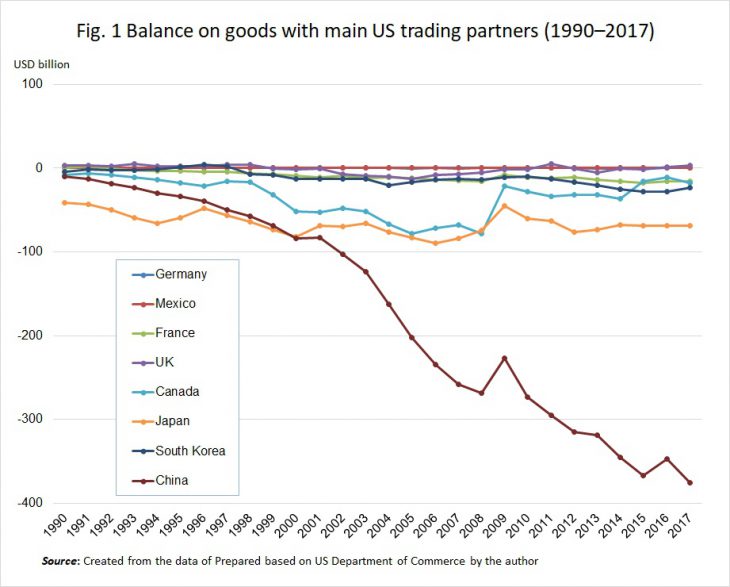

To start with, let us confirm the circumstances of international trade and employment in the manufacturing sector in the United States. Fig. 1 illustrates the balance on goods with the main US trading partners from 1990 to 2016. Since the year 2000, the US trade deficit with China has risen rapidly from USD 84 billion in 2000 to USD 347 billion in 2016, or 4.1 times the earlier figure.

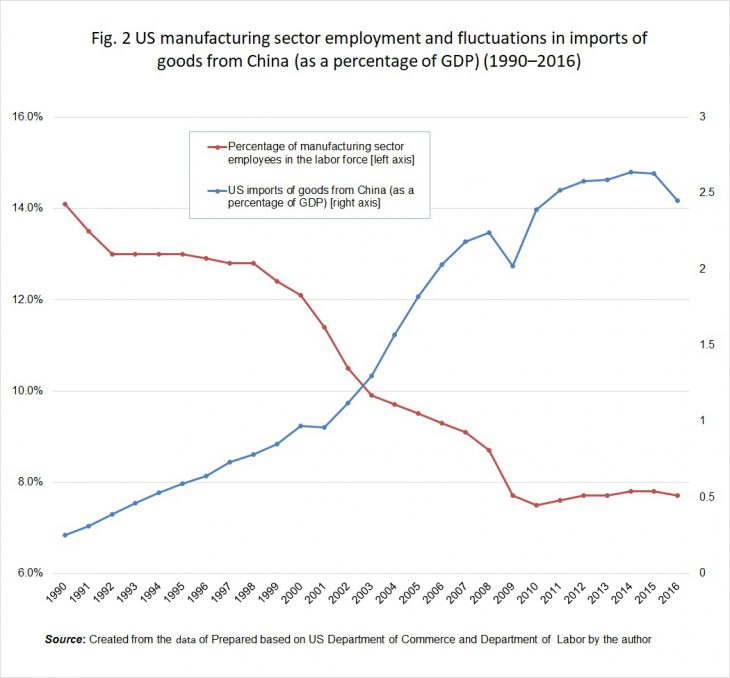

Looking at US fluctuations in imports of goods from China (as a percentage of GDP) in Fig. 2, the percentage rose from 0.25 percent to 2.45 percent in the period between 1990 and 2016. Meanwhile, the percentage of manufacturing sector employees in the US labor force retreated substantially from 14.1 percent to 7.7 percent in the same period.

If we look at other sets of statistics to find the ratio of Chinese imports to US manufacturing commodities, Chinese imports did not exceed 3.1 percent in 1990, but by 2016 they had risen sharply to 24.2 percent, or nearly a quarter of all imports. In the same period, the number of people employed in the US manufacturing sector fell by more than five million from 17.7 million (1990) to 12.31 million (2016). Even if we only look at the figures as of the year 2000 (17.26 million), the actual recorded decrease is 28.7 percent.

Seeing these figures, it is tempting to infer a causal relationship where the substantial decline in employment in the US manufacturing sector is due to the Chinese export offensive. However, such a causal relationships is not feasible without modification. The decrease in manufacturing sector employment and China’s export offensive occurred at the same time, but the introduction of IT to rationalize the manufacturing industry and changes in the industrial structure in the United States may have had a hand in the decline in employment. Other important factors may also have been at play.

To what degree has the increase in Chinese imports had an impact on the decrease in US manufacturing sector employment since 2000? US economists have been hard at work to come to grips with this question. I would like to briefly outline the results of some of the analyses (said to have opened the door to the White House for Trump).

First, what impact has the sudden increase in imports from China had on the wages and employment of US workers? Autor and Dorn analyzed this issue in their research, which created controversy and attracted the attention of experts during the election campaign.[2] One of the conclusions of their papers is that approximately one quarter of the employment decline in the US manufacturing sector can be attributed to the rapid increase in imports from China since 2000. They also reveal that workers excluded from the manufacturing sector could not be adequately absorbed into sectors other than manufacturing. The researchers used data that tracked the employment situation of individual workers over time (panel data) to statistically estimate the extent of the influence of rising Chinese imports on workers’ average income ratio, the number of years of continuous employment, and average income by year of continuous employment in the sixteen years between 1992 and 2007.

In addition, Acemoglu and Autor analyzed the influence of the rise in imports on employment and its effect on the US economy in terms of both direct and indirect effects.[3] They did detailed calculations on a nationwide scale where the direct effect is the effect of the rapid increase in imports on industries producing the same finished goods, and the indirect effect is the effect on upstream and downstream industries of a direct hit on industries that manufacture products that compete with imports. Here, I will only summarize the main conclusions.

Comparing the early 1990s with the end of 2011, the direct effect of the rise in imports from China was a loss of 560,000 jobs in the manufacturing sector. This corresponds to approximately ten percent of the loss of 5.8 million jobs in the manufacturing industry in the same period. When indirect effects are factored in, it is estimated that at this time 985,000 workers (1.98 million for the US economy as a whole) lost their jobs in the manufacturing industry alone due to imports from China.[4]

In terms of showing the extent of the impact of the China shock on the US labor market, the research is persuasive because the calculations have yielded extremely detailed and concrete figures. Broadly speaking, this suggests that ten to twenty percent of the decrease in US manufacturing employment is due to the China shock.

(2) Is protectionism the solution?

As for the second point, President Trump has set out a policy of protectionism, but will it be beneficial for the US economy? What effect will it have on the world economy?

Certainly, some of the decline in US manufacturing sector employment is due to the Chinese exports offensive, but as I already pointed out, from the perspective of macroeconomic principles, it is not possible to improve the balance of payments unless Americans rein in spending on consumption, and national savings exceed investments. Once again, I hardly need point out that even if high protectionist tariffs are introduced to oppose the (Chinese) export offensive, the problem will not be resolved. Rather, protectionism will have a negative effect on the world economy.

The Hoover Years

In the twentieth century alone, US protectionist policies were not only domestic failures, but they were also international disasters. The international economy after World War I is a classic example of protectionism gaining prominence and the development of bloc economies.

During World War I, many political and economic policy leaders in the principal countries had the vague idea that after the war the world economy would return to pre-war conditions. However, the end of the war became a historical turning point when the global situation changed in major ways. The League of Nations and other means of international cooperation failed and the economy descended into confusion and a worldwide recession.

One important phenomenon observed in the process was the segmentation of the international market and the emergence of trading blocs. Here, the war had a major impact. During the war, the warring powers were forced to develop their own industries due to the blockades on trading. Japan also developed a system of self-sufficiency in several important industries, including steelmaking and dyes, during World War I. These circumstances applied in all the warring countries. Frequently cited examples include the machine industry and the dyes needed to manufacture explosives.

Incidentally, when the war ended and trading resumed, there was a great influx from Germany to the developed countries of good-quality and cheap steel, machines, dyes and other industrial goods. As a result, the countries that were nurturing these industries resorted to high tariffs to prevent imports and to protect their own industries. These measures led to the establishment of import quotas and other disadvantageous tariff barriers, including retaliatory tariffs, as the trend to block the influx of goods from other countries accelerated. This is one aspect of the mechanism of the protectionist chain.

A turning point in world history came in June 1930 when the US Congress enacted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which introduced high tariffs focused on agricultural produce—a move that the rest of the world saw as the go-ahead for high tariff policies. At the time, nearly one thousand economists in the United States petitioned President Hoover not to sign the Tariff Act, but the President disregarded the logic of economics and signed the bad legislation.

As Douglas A. Irwin (2017) points out, the introduction of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was one of the reasons for the Great Depression, but in Canada, for example, the US protectionist stance led to a change of government when a pro-American Liberal administration was replaced with a protectionist conservative administration that turned Canadian trade policy toward protectionism focused on a policy of retaliatory tariffs.[5] Seeing the current situation in this light, Irwin claims that high tariffs on imports from Mexico have the potential to prompt the emergence of an anti-American presidency and to intensify economic nationalism. He also argues that Mexican nationalists may forge a united front with Cuba, Venezuela, and other ultra-leftwing governments in Central and South America.

The Reagan Years

In actual fact, discussions that ignored basic macroeconomic relationships in the same way that Trump does were prevalent in the United States more than thirty years ago. It was the time of the Reagan administration when the United States engaged in aggressive “Japan-bashing” and used Section 301 under the Trade Act (Super 301) to designate Japan an unfair trading partner. Looking at Fig. 3, the reasons for the start of Japan-bashing become clear. However, preventing imports from Japan by no means solved the problem. Despite the appeals of intelligent and sensible US economists (Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow, Franco Modigliani), who pointed out the extent to which Reagan’s protectionist policies were an affront to common economic sense, the appeals were dismissed out of hand and US trade policy in the 1980s became centered on protectionism.

As expected, the policy of raising barriers to trade under the Reagan administration did not always result in the revitalization of key industries in the United States. A report by the Congressional Budget Office stated that “Trade restraints have failed to achieve their primary objective of increasing the international competitiveness of the relevant industries.” (Has Trade Protection Revitalized Domestic Industries? Nov. 1986, p. 101). In other words, most of the shocks inflicted on US industry had nothing to do with trade and imports did not decrease due to the relief measures.

What then caused the manufacturing industry to retreat under the Reagan administration?[6] One factor was the fiscal austerity measures at the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) to deal with progressive inflation. A major factor was the rise in the value of the dollar by 40 percent in the four years from 1981, causing the products of the US manufacturing industry to lose their export competitiveness. There were also other important structural factors. In the steel industry, manufacturers of low-cost electric furnaces captured market share from large-scale blast furnaces while the shift toward a demand for high-quality compact cars with good fuel consumption impacted on the three major automobile manufacturers.[7]

On the other hand, US consumers were dealt a severe blow when the price of Japanese cars rose by an average of 16 percent due to the import restrictions implemented by the Reagan administration in the early 1980s. The import restrictions on steel imposed high costs on the downstream industries that use steel while the restrictions on imports of textiles and apparel raised the cost of living, pushing low-income households into a difficult situation.

Trying to protect domestic industry with protectionist policies, the United States committed a serious blunder in the 1980s. Unless the Trump administration acknowledges this point, it is possible that the US economy will slip from its position as a high-flyer among developed countries of the past two years.

The biggest risk posed by the return to the Reagan years, which it must be said is the essence of Trump’s policy on trade, is that the GATT and the WTO, the multilateral free trade organizations that the world has worked so hard to build in the wake of World War II, might collapse, provoking retaliatory tariffs.

In other words, if Trump’s trade policy is to stockpile cash and to create a trade surplus by means of high import tariffs and export subsidies, it is the equivalent of the delusional mercantilist policies that create wealth for one country (sharply criticized by Adam Smith 250 years ago). The accumulation of foreign currency is not the focus of attention of a country’s economy. Expanding production and consumption through trade is linked to the creation of wealth.

What’s behind the weakening of the high tariff effect?

In any case, the main reason for the decline in employment in the US manufacturing industry today is not the trade deficit with China. The number of jobs in the US manufacturing industry started to decline in the 1960s due to technical innovation and rising productivity, so the prominence of the Chinese economy is not the sole reason. Reducing imports from China will not recover employment in the United States.

Rather, where trade policy is concerned, the United States should consider how trading structures have changed in important ways in recent years. The increase and prevalence of direct investment is one of the main features of the modern world economy. According to UNCTAD data, the FDI outward stock worldwide was USD 2,253.9 billion in 1990, but by 2016, it had increased more than tenfold to USD 26,159.7 billion.

Multinational corporations conduct their business activities around the world through direct investment. The US manufacturing industry set up overseas manufacturing subsidiaries at an early stage, spreading global production and sales systems. If we look at the statistical data on US multinational corporations, sales by overseas subsidiaries of the US manufacturing industry reached USD 2,657.3 billion in 2014 (US Department of Commerce). This amount is nearly twice as high as exports of manufacturing industry commodities from the United States to countries worldwide (USD 1,408.8 billion in the same year).

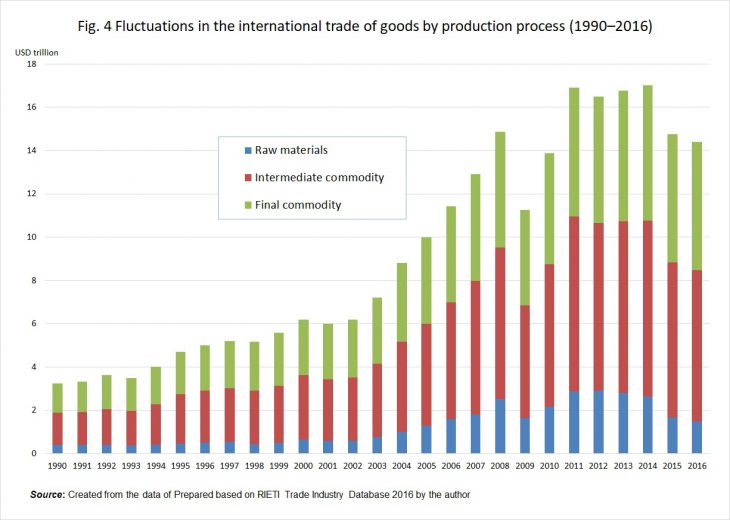

Another special characteristic is that the tradable commodities are not the final products, but most of them are intermediate commodities. With the advance of globalization, production is no longer completed in one country, but a global supply chain is formed through trade. Looking at the fluctuations in the trade of goods by production process illustrated in Fig. 4, we can confirm that the trade in intermediate commodities increased from USD 1,490.8 billion in 1990 to USD 7,435.0 billion in 2001. Different kinds of intermediate commodities, including machine components and processed goods, are transacted within this global supply chain, but should imports of any of them stagnate, the production activities of any country involved would be dealt a fatal blow.

Computers and electronic devices, electrical equipment, household appliances, and their components account for roughly half of US imports of goods from China. Most of them are final commodities (however, these final commodities are the products of an international division of labor in the East Asia region), but the situation is completely different where trade with Canada and Mexico are concerned. Since the North-American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect in 1994, the international division of labor between the United States and Canada, and between the United States and Mexico has become far-reaching, and there is an extremely high level of economic interdependence due to direct investment and trade. The automotive industry is a classic example. Nearly half of US imports of automotive parts come from Canada and Mexico (according to the Center for Automotive Research, NAFTA Briefing, January 2017).

What would happen if a policy of protectionist tariffs is implemented where a framework of international division of labor has been created? The import restrictions may cause corporations in the upstream industries in the United States to raise prices. However, from the perspective of corporations in the downstream industries, imposing high tariffs on the intermediate commodities used in their production processes would lead to sudden price increases, dealing these companies a major blow and causing them to lose competitiveness on the international markets. These downstream industries normally employ more people than the upstream industries. Consequently, there is a high likelihood that more people will lose their jobs at companies in the downstream industries than the number of jobs that will just about be preserved (or recovered) in the protected industries. Since the automotive industry is a classic example of a downstream industry, the impact is unfathomable.

In addition, among developed countries, the United States is exceptional in the sense of its low dependence on trade, but even so, the amount of trade has been rising in recent years, so the impact of retaliatory tariffs would likely be greater than in the 1930s or the 1980s.

Is China advocating free trade?

In the modern era, there has always been a country that has attained economic supremacy. In the nineteenth century, it was Britain, the success story of the world’s first industrial revolution, which established itself as the world’s factory, supplying the best quality industrial goods for a long period. Consequently, even though the country was open to free trade, the foreign export offensives did not deal the domestic industry any fatal blows. In addition, Britain had already made overseas investments and built up adequate military, political and economic power to develop an international strategy. In the case of grain alone, it was clearly cheaper to rely on overseas imports as the cost of producing grain in Britain was high. If British workers could survive on cheap grain, Britain would have a comparative advantage and be able to keep down the prices of industrial goods, thus increasing its international competitiveness. But there were reasons for Britain choosing to abolish tariffs on grain and to advocate free trade. The emergence of the theory of the free trade advantage as the theory representing the industrial capitalists (not the land-owning classes), who compete on the international market, is taught in the history of economics doctrine. Britain was a strong advocate of the theory of free trade because it would bring the country great advantages, but British advocacy was by no means rooted in any theoretical clarity on the advantages of trade.

Thus, Britain abolished the Corn Laws in 1846 and established the basic guidelines for its trade policy to ensure free trade. It was an expression of the firm confidence of an international economic superpower. The theory of free trade became prevalent outside Britain because it gradually became evident that latecomers could recreate the logic of the British experience as the principle of comparative advantage. In short, at the stage when it became clear that free trade would bring advantages to those involved, many countries started to set out their positions with regard to the principles of free trade.

Here, it must be noted that at the stage when the world joined the system of free trade, there was a leader to manage and supervise the system. It was vital to have a nation with the ability to maintain the trading systems and world economic order in a stable manner. Britain filled that role until World War I, but the country’s ability to lead declined as a result of the chaos of the interwar years. It hardly needs to be said that after World War II, it was the United States that took on the role of anchor for the world economic structures.

But what is happening now? At the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) at Davos, Switzerland, in January 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave a keynote address where he emphasized the importance of globalization and free trade, saying “No one will emerge as a winner in a trade war.” People who subscribe to stereotypical political views were surprised and may even have thought the ideas brazen. However, there is no doubt that President Xi was amazingly persuasive in his use of similes (“Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room. Wind and rain may be kept outside, but so is light and air.”), or when he said that countries should not sacrifice other countries in pursuit of their own advantages.

Comparing this speech with the inaugural address by President Trump, who took office shortly after, one is startled anew to realize we have arrived at a turning point in time where it is difficult to say with certainty which speech was made by which country’s representative.

Simply put, revived after an interval of two hundred years, China has attained rapid growth and entered the international marketplace to become a champion of free trade in contrast to the United States, which is barricading itself behind protectionism. China is advocating free trade and the United States is embarking on protectionism. Such a retreat in the relative position of a past dominant power indicates that the country has become estranged from the international economic order.

As if to hint at the sudden reversal of the position, the transition phase is hardly likely to progress smoothly, but it is also difficult to imagine that the polarized system will continue for a long time. Assuming that US protectionism is not confined to issues of trade and economic performance, the maintenance of the political and economic power of the United States, i.e., its hegemony, is also involved in some way.

How do we respond to the internal contradictions of “learning from history” or “repeating history” mentioned at the outset of this article. The role and limits of economics is a key factor. The logic of economics as intellectual legacy is able to clearly point to the inconsistencies between policy intent and outcome. However, politics move in spite of these inconsistencies. President Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act regardless of the petition signed by more than one thousand economists. Something similar occurred again under the Reagan administration.

Under the Trump administration, it is possible that no one will pay any attention to the power of economics or the opinions of economists due to the shortsighted perspectives of politicians and citizens. In the long term, the negative economic consequences of protectionism taught by economics are not mistaken. However, in realpolitik, the doctrine that “no one will emerge as a winner in a trade war” is only accepted as something extremely inconvenient for winning elections.

In other words, citizens do not learn from history in the absence of a long-term outlook or awareness of the public good. If we only focus on scientific development or technological progress, it would appear that humanity becomes increasingly intelligent. However, there is apparently every reason to agree with Professor Kindleberger’s pessimistic theory that far from making progress, humanity is simply repeating history and losing wisdom in the process.

Economic gains alone do not move politics. Conflict and tense relations between nations do not always originate in economic problems. As is the case with individuals, nations also have their points of pride and self-esteem. When there is conflict between nations, violence (the ultimate reasoning) may be invoked when pride and self-esteem have suffered an injury—which is also what happens when children quarrel.

Even so, there is no doubt that economic interests provide the foundation for a range of both domestic and international conflicts. The least harmful method of solving such short-term conflicts of interest is neither plunder nor protectionism, but to get to know the other party through free exchanges and trade, and to gradually adapt to the changes. We must once again remember that international trade as an important means of keeping the peace was first emphasized in Western European society in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries at a time when society was split, and conflict and separation was extreme due to religious conflict.

Seen in this light, we need to be familiar with the economic logic of trade, and to reflect on the consequences of ignoring that logic. It is now more important than ever to emphasize the importance of what we learn from history.

Translated from “Tokushu—Toranpu Seiken kara Ichine: Rekishi kara manaberunoka, rekishi wa kurikaesu dakenanoka (Special Issue—One Year Since Trump’s Election: Can we learn from history, or do we simply repeat history? — Trump’s trade policy from an economics perspective),” Chuokoron, December 2017, pp. 94-107. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [December 2017]

[1] Below, the quantitative understanding of trade structures is based on the results of my own work where the Asia Pacific Institute of Research (2017) is indicated. For details, please refer to the publication.

[2] Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2013), Autor, Dorn, Hanson, and Song (2014)

[3] Acemoglu, Autor, Dorn, Hanson and Price (2016)

[4] According to the same paper, it is conceivable that employment in other domestic industries increases when a particular industry is directly hit by imports from other countries, but in the period under consideration, there was a substantial decrease in overall demand in the United States (consumption and investment) so there was no link to increased employment.

[5] Irwin (2017) p. 42

[6] Irwin (2017) p. 36

[7] Inoki (1998)

Keywords

- Tramp’s trade policy

- C. P. Kindleberger

- Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crisis

- Bubble economy

- Lehman Brothers bankruptcy

- America First

- protectionism and exclusivism

- WTO

- TPP

- China shock

- protectionist chain

- Hoover

- Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

- Japan-bashing

- Super 301

- Reagan

- GATT

- global supply chain

- NAFTA

- international division of labor

- Xi Jinping