Issues after the Lower House Election: Developing an Environment to Improve Private Sector Vitality

Komine Takao, Professor, Taisho University

Key points

- Uniform benefits go to savings and do not boost consumption

- Overall income slump is more severe than widening disparities

- Speed up industrial and corporate metabolism and regulatory reforms

Prof. Komine Takao

Following the lower house election, I would like to consider the future direction of economic policies. The Kishida administration’s economic policies have so far only consisted of slogans such as “a new form of capitalism,” “Reiwa double income,” “without distribution, there will be no subsequent growth,” and “neoliberal policy shift.” Depending on how these are concretized in the future, they may take the economy in a good direction or in a bad direction.

The first thing that will be required of future economic policies is a switch from election mode to practice mode. Election mode, which has been active throughout the Liberal Democratic Party presidential election and the Lower House election, emphasizes only the benefits of policy while obscuring the necessary costs. During the Lower House election, the parties have exclusively been advertising their policies without clarifying where the money will come from.

Yet, were they able to convince the people? Neither the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ) nor the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) were able to secure more seats in the Lower House election. Some have pointed to the opposition parties’ failure to cooperate, but I think it might have been that the public did not accept the details of their policies. Many opposition parties have proposed blatant pork-barrel policies such as reducing or abolishing consumption tax, income tax cuts, and benefit payments that go directly into people’s wallets. Voters might have been put off by this, thinking that “It sounds too good to be true.”

With this sound reaction in mind, it is necessary to approach policy in practice mode from now on. In formulating the supplementary budget and the budget for the next fiscal year, it will be necessary to go through the contents of government spending and aim for wise spending while clarifying where the funds will come from, carefully explaining how a balance with fiscal consolidation will be achieved.

Secondly, they must not forget the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. In the unprecedented battle against this infectious disease, there was no choice but to develop economic policies on a trial-and-error basis, but the errors ought not be repeated. Let me give you two representative examples of errors.

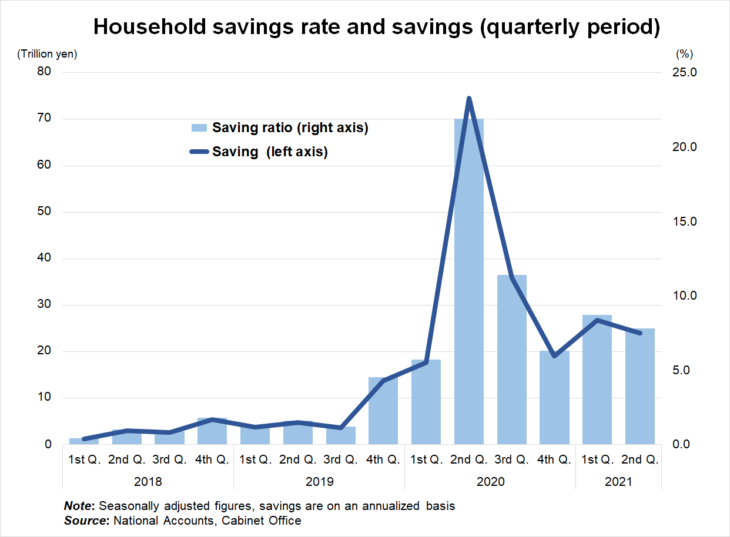

One is a uniform 100,000-yen benefit payment to all citizens in the spring of 2020. What happened to household income back then? According to the Cabinet Office’s “National Accounts,” household savings increased sharply in the April-June quarter of 2020, and the household savings rate, which shows the ratio of savings to disposable income, reached an unusually high level of 21.9% (see figure). Although employee compensation (wages) decreased, an additional 100,000-yen benefit was added in a situation where household consumption had decreased and savings increased even more. From a macroeconomic perspective, those 100,000 yen went straight into savings.

Since then, even after the effect of the 100,000-yen benefit has disappeared, savings have continued at a high level. In the April–June quarter of 2021, the household savings rate was at a high level of 7.8% (the pre-pandemic household savings rate was 1–2%). Households as a whole remain in a state of surplus, so further benefit payments will not increase consumption. In the future, if concrete plans for some kind of benefit payments are made, it will be necessary to closely examine their purpose and effects.

The other example is the “Go To campaign.” In-person service consumption (travel and dining out), which has an infection risk, is “external diseconomy.” The textbook answer is to tax entities that caused the external diseconomy or subsidize entities that do not. But Go To subsidized the entities that cause the external diseconomy. If we want to resume Go To in the future, it is necessary to sufficiently ensure consistency with infection risk responses.

Thirdly, the goal should be to implement policies backed by economic logic and data. Let’s take the issue of distribution and disparity that all parties discussed during the Lower House election as an example. Everyone is fully aware of the importance, and it has been discussed to death by many debaters. All I will do is list a few points from a macro perspective below.

Looking at macro data on the economy and society as a whole, we can conclude the following. Firstly, the claim that disparities have widened under Abenomics is false. The Gini coefficient, which is an important disparity indicator, went down from 0.3791 in 2011 to 0.3721 in 2017, which indicates less disparity (“Survey on income redistribution,” Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare).

Likewise, there is little evidence for the claim that the middle class has shrunk in recent years. 92.8% of the population thinks their lifestyles are roughly intermediate (total of lower intermediate, middle intermediate, and upper intermediate in 2019). The most recent five-year average (2013–2019) shows that 57.1% consider themselves “middle intermediate,” which is actually higher than the earlier five-year average (55.7%) (“Public Opinion Survey Concerning People’s Lifestyles,” Cabinet Office).

Seen internationally, Japan is not a country with particularly large economic divides, and the Gini coefficient is average among developed countries. On the other hand, there is a lot of data showing that nominal income and wages as a whole have not increased in Japan. Nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the last decade (2011–2020) has been an average 0.7%, with employee compensation growth also recording no more than 1.2%. That is slow growth by the standards of developed countries.

In light of this, I suspect that many people misunderstand the income slump to be due to widening disparities. If so, creating an environment for economic growth and sustainably raising the overall income level (so-called growth strategy) becomes a silver bullet to dispel disparity consciousness.

I will also say something about the logic of the relationship between economic growth and distribution. The idea that “without growth, there will be no subsequent distribution” is correct because the resources for distribution become available only when there is economic growth.

At the same time, it is true that when the distribution goes from high-income earners to low-income earners, consumption demand increases and growth is promoted because propensity consume is higher among low-income earners. Yet whether economic growth is visibly promoted is another matter. Common sense dictates that it is difficult to promote growth through this mechanism unless the income is redistributed at an unrealistically grand scale. It is somewhat suspicious whether it is true that “without distribution, there will be no subsequent growth.”

The truth is that creating new added value, achieving economic growth, and boosting income overall has the potential to help resolve more or less all economic issues, not just that of distribution. Growth increases the sustainability of the social security system, stabilizes employment, and makes public finances easier. Above all, higher income means happier people. I think it is right to say that “without growth, there will be nothing.”

Nonetheless, it is difficult to increase the underlying growth potential through policy alone. Although many cabinets have worked on growth strategies, the underlying growth rate remains inferior to those of other developed countries. Simply increasing fiscal spending or easing finance is not enough to accomplish this.

Since growth is basically achieved by private companies and human resources, the government can do nothing more than create an environment that enhances the private sector vitality. Indispensable to this are regulatory reforms that promote industrial and corporate metabolism, change workstyles, and facilitate increased productivity.

This may contradict Prime Minister Kishida’s slogan “neoliberal policy shift.” If it slows the progress of regulatory reforms, we might end up with “slogan concretization that takes the economy in a bad direction” as described in my first example.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 10 November 2021 under the title, “Shuinsengo no Kadai (II): Minkan no katsuryoku kojo he kankyoseibi (Issues after the Lower House Election (II): Developing an Environment to Improve Private Sector Vitality).” The Nikkei, 10 November 2021. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Komine Takao

- Taisho University

- Lower House election

- Kishida administration

- slogans

- “neoliberal policy shift”

- private sector vitality

- economic growth

- benefits

- savings

- consumption

- income slump

- wages

- disparities

- regulatory reforms

- government spending

- household savings rate

- COVID-19

- Go To

- middle class