Pros and Cons of China Joining the CPTPP: An Opportunity to Negotiate Membership and Take Corrective Action on Problems

Ito Shingo, Senior Economist, Institute for International Economic Studies

Key points

- Aim to reduce dependence on the United States and contribute to the global economy

- Membership will inevitably require major adjustments to the economic system

- Negotiations should consider China’s economic characteristics and security exceptions

Ito Shingo, Senior Economist, Institute for International Economic Studies

On September 16, China applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Membership of this high-level FTA will however inevitably require China to implement bold reform and opening up, giving rise to various observations regarding the true motive behind its application and the seriousness of its intention.

In this regard, the Chinese government has stated that its application to join the CPTPP signals (1) its will and commitment to achieving continuous deepening reform and opening up further; and (2) its support for free trade and its will to contribute to the recovery and growth of the global economy through the active promotion of regional economic integration together with the liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment.

There is clearly a keen awareness of the need for deepening reform and further opening up, given the increasingly important and pressing need to improve productivity. The decline in labor input due to the declining birthrate and aging population as well as the fall in the savings and investment rate due to a shrinking population could gather pace in the future. Moreover, growth that is dependent on real estate development is at a crossroads.

The Chinese government is ready to stimulate innovation and economic efficiency by creating a level playing field through the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025). As part of such efforts, the central party may have accepted to some degree the notion of using the CPTPP to apply outside pressure on Chinese companies to increase productivity, a strategy long advocated by Chinese reformers.

It may also be that the intensifying confrontation between China and the United States coupled with the materialization of supply chain risks due to COVID-19 have increased the strategic value of opening up to the outside world through accession to the CPTPP. Strengthening economic ties with CPTPP members would enable China to stabilize its supply chains and reduce its dependence on the United States.

The Chinese government is hurriedly constructing a “dual circulation” model that will lead to high quality growth through a virtuous cycle of both domestic and foreign demand. This model hinges on ensuring high-quality development and national security by leveraging both the expansion of domestic demand through reform and the opening up of China’s economy to make strengthened economic relations with China a more attractive prospect for other countries, while at the same time encouraging other countries to open their markets to China. The application for CPTPP accession is an important means to achieve this end.

According to estimates by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, China’s accession to the CPTPP would allow it to expand its real income by 1.1% as of 2030. It is also estimated that the share of China’s total exports to and imports from the United States would be reduced by 2 percentage points and 1 percentage point respectively, while the share of exports and imports to CPTPP members would be increased by 7 percentage points and 8 percentage points respectively. Further, China’s accession would lead to a 0.5% increase in global real income, which would also achieve the additional purpose of “contributing to the recovery and growth of the global economy.”

However, a large disparity still exists between China’s political and economic system and the trade and investment rules for CPTPP membership. Numerous concerns have also been presented with regard to compliance with WTO Agreements, which require a lower level of liberalization than the CPTPP.

Commentators have noted that China’s accession to the CPTPP faces significant hurdles in diverse areas. These include freedom of association and recognition of the right to collective bargaining, and acceptance of the CPTPP Three Principles on e-commerce (free data flow, general restriction on data localization, and ban on mandatory source code disclosure).

State-owned enterprises are expected to pose a particular challenge in this regard.

The CPTPP requires state-owned enterprises to act in accordance with commercial considerations and principles of non-discrimination when engaging in commercial activities. However, China’s state-owned enterprises are expected to play a role that goes beyond commercial considerations, including that of ensuring macroeconomic stability.

Further, the CPTPP rules prohibit the provision of non-commercial assistance to a company on the grounds that it is “state-owned” if it would have an adverse effect on the interests of other parties to the agreement. Non-commercial assistance refers to donations and debt relief; provision of loans, debt guarantees, goods, and services on more favorable than market terms; and investments that do not conform to the normal investment practices of private investors. However, the Chinese government has positioned strategic emerging industries (next generation IT = information technology, biotechnology, new energy, new materials, new energy vehicles, etc.) as areas in which to concentrate state-owned capital through optimization of deployment and expansion of scale, and is providing various forms of support to that end.

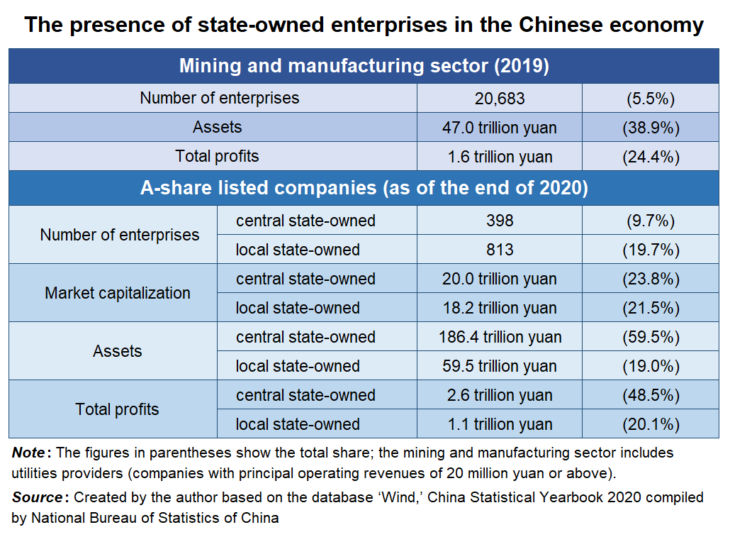

China’s Constitution positions state-owned enterprises as a fundamental institution of the state, stipulating that the state-owned economy is the “leading force in the national economy” and that the state ensures the growth of the state-owned economy. It will not be easy to reconcile the CPTPP and state-owned enterprises, which still have a significant presence in the economy (see table).

In spite of this, some are of the opinion that the Chinese government applied for membership because it believes that its strong economy will enable it to secure reservations in areas such as state-owned enterprises, thereby lowering the hurdle for membership. Some observers have suggested that after joining the CPTPP, China will use a large number of security exceptions to protect its own political and economic system.

Some even believe that CPTPP accession is more about China seizing the initiative with a view to shaping the trading order in the Asia-Pacific region. Holders of this view maintain that even if the CPTPP’s activities are hindered by the disagreement over China’s access to the CPTPP, China can still show initiative in shaping the trade order around the RCEP, which it has been actively promoting.

Be that as it may, China’s accession should not be rejected out of hand. Japan will benefit from having more CPTPP members on condition that they comply with and implement all existing rules and adhere to the provision of the highest level of market access. During the course of negotiating China’s accession, Japan and other parties to the agreement should urge the Chinese government to make its policies transparent and to respond in line with the aforementioned will and commitment. In the process, Japan will gain a better understanding of China.

In discussions regarding China’s accession, attention needs to be paid to the characteristics of its economy. For example, many of the obligations in the state-owned enterprises chapter of the CPTPP agreement do not apply to local state-owned enterprises, which are very large and influential in China. The way they are dealt with in the CPTPP will be subject to additional negotiations within five years of the CPTPP coming into force, which will need to be taken into account when regulating the treatment of China’s local state-owned enterprises. Another potential area for debate is the influence of party organizations within corporations on corporate governance pertaining to the definition of state-owned enterprises.

A further issue of importance is the weakening of CPTPP rules by the frequent use of security exceptions, which must be avoided. The Chinese government’s security concept (a Holistic Approach to National Security) encompasses a broad range of more than ten areas such as politics, land, military, economy, culture, society, science and technology, information, and resources. A review of trade/investment management legislation is imperative to ensure that industries are not protected in the name of national security.

Meanwhile, Japan also needs to factor in consistency with international trade rules when developing its own economic security system. Japan’s choice of target areas and means of ensuring security are highly likely to impact China’s choices. In addition, Japan should join other countries in urging China to make greater efforts to ease tensions on the security front so that we can expand and deepen our economic relationship through the CPTPP agreement with confidence.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 5 November 2021 under the title, “Chugoku, TPP sanka no zehi (II): Kameikosho, mondaiten zesei no koki (Pros and Cons of China Joining the TPP (II): An Opportunity to Negotiate Membership and Take Corrective Action on Problems).” The Nikkei, 5 November 2021. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Ito Shingo

- Institute for International Economic Studies

- China

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

- state-owned enterprises

- state-owned capital

- state-owned economy

- free trade

- liberalization

- 14th Five-Year Plan period

- “dual circulation” model

- strategic emerging industries

- United States

- Japan

- security