Russian Violence and a Shaken Order: A “Crisis from an Eagerly Awaited Yen Appreciation” Posing a Greater Risk than the Situation in Ukraine

“There is nothing the Japanese government can do directly to address the current surge in resources prices. The priority should be to minimize the contraction of domestic economies. This requires an expansion of government spending.”

Iida Yasuyuki, Professor, Meiji University

Changing politics, society and security and the impact on the world economy

Prof. Iida Yasuyuki

What is the biggest economic risk that Japan will face as a consequence of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? It is neither soaring energy prices nor inflation. It is the warping of decision-making on economic policy because of too much attention being paid to the huge changes in the international situation.

News outlets file reports on devastated cities, countless victims and barbarous acts by the Russian military on a daily basis. The Ukrainian population is about 42 million (Russia about 147 million). The country’s GDP per capita is only about $3,700 (Russia’s is about $10,000), which really is not much at all, but the fact that a modern state in a corner of Europe has been hit with an all-out invasion will surely bring about large and irreversible changes in world politics, society and security.

Compared to these changes, the impact on the world economy is not big at all. We must not fail to discern this disparity in relative impact. If we pay too much attention to changes in politics, society and security and opt for irrational economic policy in what may be termed a panic, then that is likely to throw a shadow on the Japanese economy that is longer than the Ukraine crisis.

Public opinion changes as resource and food prices increase

The economic ties between Russia and Ukraine on the one hand and Japan on the other are not particularly significant. Japan’s total exports to Russia are 0.9 trillion yen and its total imports from Russia are 1.5 trillion yen, which amounts to shares of no more than 1–2% of total exports at 83.0 trillion yen and total imports at 84.5 trillion yen (2021). The trade with Ukraine is less than one-tenth of that with Russia. As such, if we exclude rare metals such as palladium, fisheries and such, the impact on the Japanese economy will be primarily indirect, via energy and energy prices. Moreover, increases in food prices for wheat and other products only has a small impact on the macroeconomy, but we also need to recognize that the impact it has on policy decisions cannot be ignored.

International increases in energy prices have undoubtedly gained steam since the invasion of Ukraine. However, do we have a correct perception of its quantitative impact?

The WTI Crude Oil Futures Prices, which trended around $50 per barrel in 2019, fell below $20 on April 20, 2020 (temporarily falling to nearly $0). After that, the price increased as countries responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, hitting $80 in October 2021. Amid growing concerns about a Russian invasion, it temporarily soared above $130 per barrel, but as of April 1, it is in the range of $100, which is not much different from what we saw in February. Excluding the surge after the invasion, the current high oil price is not far from the upward trend since last year. A price in excess of $100 per barrel is something we already had intermittently from spring to fall in 2008 and again in the period 2011–2014.

Whatever the cause, it is certain that a price surge is not desirable for Japan as an energy importer. The corporate goods price index (CGP) rose 9.7% on the previous year in February, the biggest jump since 1980. Regular gasoline prices have also surged to 174 yen per liter (as of April 11, 2022), and taking into account subsidies to wholesale dealers of oil products, it seems to have reached a level exceeding the old record from 2008 (185 yen per liter).

Moreover, wheat prices have climbed as Russia and Ukraine, some of the world’s biggest producers of wheat, fight their war. But wheat prices have a small impact on Japan’s overall price levels. Even wheat-related expenditures in a broad sense, including bread, noodles, and eating out, account for less than 5% of household consumption (“Household Survey,” Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications).

However, the rise in gasoline and food prices, as frequently purchased goods, raises the “experience inflation rate.” By the way, the actual inflation rate is expected to rise by 0.9% of the consumer price index (CPI) (overall) on the previous year, and even if the effects of last year’s cell phone rate cuts dissipate after April, the rate of increase is expected to be around 1.5%. Whatever the criterion we apply, this degree of price increase cannot be called a “high rates inflation.”

In response to the anxiety of soaring costs for companies and an increasing experience inflation rate for households, it has recently become more and more common for people to call for an appreciation of the yen or to talk about the ills of the yen’s depreciation. Partly due to a shift in monetary policy in the United States, where the CPI rose more than 8%, the Japanese yen has fallen sharply on the exchange market since the beginning of March. The yen-dollar exchange rate, which was around 110 yen last year, is in the 128 yen range (as of April 28), giving us a yen depreciation.

The invasion of Ukraine in combination with COVID-19 has heightened the anxiety of companies and households. The rapid depreciation of the yen has created the illusion that it is a major factor in the current economic problems. However, the main reason for the rise in domestic food and energy prices is not the weaker yen.

Misunderstandings about terms of trade

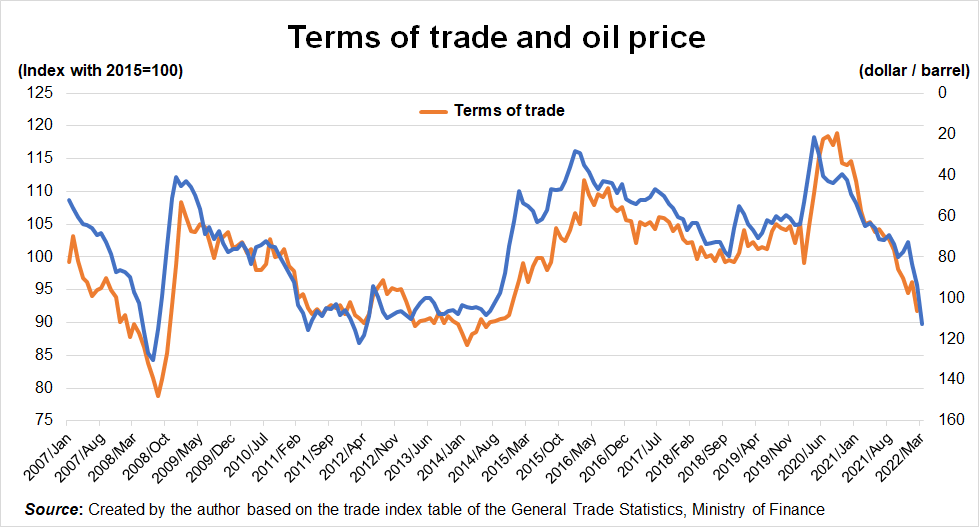

An economic index that is often mentioned when discussing the demerits of a weakening yen is terms of trade. There are many arguing that the yen depreciation is impoverishing the Japanese economy through a deterioration in the terms of trade. I was surprised recently to see an economic newspaper write “(The current yen depreciation) indicates a significant deterioration in terms of trade due to the (demerits of a) sharp rise in yen-denominated import price.” Then, I was once again surprised when I saw that the author was a research director of a famous stock company. This is a complete misunderstanding. The terms of trade is the ratio of export prices to import prices. It helps to understand it as “the amount of crude oil” that can be purchased with the money from “selling one car overseas.” From this, some people may think that if the yen weakens, the amount of crude oil that can be purchased for the price of one car sold will decrease as the price of Japanese cars overseas becomes cheaper. But that does not happen in the real world. Many of the overseas sales prices of Japanese products are dollar-denominated. Even if the exchange rate changes, it will not reduce the price of a product from $10,000 to $9,000. There are quite a few exports settled in yen, but most of them are transactions between Japanese companies and their affiliated overseas companies. The impact of the exchange rate on the ratio of Japanese car prices to crude oil prices in the United States is small. So, what has caused the deterioration in the terms of trade in recent years? It is the soaring international prices of resources and energy. Looking at evidence rather than theory, let us compare changes in the terms of trade and changes in the crude oil price (Dubai) over the past 15 years (see figure).

The two trends are indistinguishably consistent. The terms of trade of how much in terms of import goods you can buy with Japanese export goods do not represent Japan’s national power or what the world thinks of Japanese products, but it is no exaggeration to say that it is determined by resources prices alone. Moreover, international resources prices are not changed by Japan’s economic policy.

For the sake of argument, let us say that the argument that the yen’s depreciation is deteriorating the terms of trade stems from a mixing up of terms of trade and the real exchange rate. To be sure, the two are often discussed in close proximity in texts on international economics. Incidentally, the real effective exchange rate, which is used to give the impression that the current yen depreciation is peculiar and abnormal, is the average value of the real exchange rate of multiple countries (using trade value weighted average). In terms of the normal exchange rate (nominal exchange rate), the current yen depreciation is at a level we experienced around 2015. In 2001, the yen depreciated to the 130-yen range. Meanwhile, looking at the real effective exchange rate, it seems that it we are currently seeing a weaker yen than in 1972 under the fixed exchange rate system.

Exchange rate and real exchange rate

The real exchange rate is sometimes described as an exchange rate that takes into account the price index, but this is not very accurate. In fact, it represents “how many units of a good that can be purchased in the United States” after selling “one unit of a good in Japan,” acquiring yen, and exchanging that for dollars on the foreign exchange market. If you exchange “yen earned by tutoring for one hour in Japan” into dollars, it is good to think of it as “how many hours of tutoring can you receive in the United States.” If the exchange rate is 1 dollar = 120 yen, the real exchange rate = 120 × (American price index ÷ Japanese price index) (actually, the real rate in the base year is 100, while subsequent changes are indexed).

If this is the case, the real exchange rate will show a weaker yen whenever the exchange rate produces a weaker yen. From the sound of the word “real,” many people seem to feel that the real exchange rate is a more essential and meaningful number, but this is not the case. It is a customary designation that comes from the expression “realization” in economic statistical terms to multiply prices and the ratio of prices.

Why is the depreciation of the yen in terms of the real exchange rate more advanced than that of the general exchange rate? Now, recall the definition of real exchange rate. In Japan, there is little Japanese yen that can be obtained by selling one unit of a good; that is, in a deflationary phase, the real exchange rate will show a weaker yen. Currently, inflation in the United States is in the range of 8%, while in Japan it is less than 1%. Here, the discussion returns once more to the issue of deflation (or low inflation, to be precise).

The fear of deflation brought about by inflation

Japan’s economic policy will not be able to cope with the current surge in resources prices. What can be done is to devise ways to prevent the negative effects of the soaring resources prices from leading to a deterioration in the economy.

Gasoline and food, for which prices are currently soaring, are typical necessities, much of it imported. It is difficult to reduce the consumption of essential goods even if the price rises. As a result, higher spending on necessities reduces demand for other goods, many of which are produced in Japan. Reduced demand for domestic products will encourage lower prices for those products, meaning we get deflationary pressure. The CPI (core-core index), excluding fresh food and energy, as of February is minus 1.0% compared to the same month of the previous year. This shows that have yet to properly exit the deflationary phase.

The already apparent rise of the corporate goods prices also puts deflationary pressure on domestic economies. Companies that produce goods and services for the domestic market are also purchasing various resources as raw materials. Even if resources prices soar, it is difficult to raise prices significantly in a situation where domestic demand does not change. As such, the high resources prices will be absorbed by a decline in corporate profits or labor costs. The former will reduce the willingness of wealthy people to consume through a decline in stock prices and other factors. At the same time, it goes without saying that a reduction of labor costs puts a deflationary pressure on domestic economies.

Is it appropriate to use the exchange rate, or monetary policy to change the exchange rate, to solve this problem? It is true that since the domestic energy price is multiplied by the exchange rate denominated in US dollars, an appreciation of the yen might be able to suppress the energy price denominated in yen. However, as of April, while the oil price had doubled compared to 2019, the exchange rate showed the yen depreciating by about 10%. Even if strong monetary tightening could raise the exchange rate to 2019 levels, it is impossible for it to lower the prices of domestic resources, energy and food prices to a level that companies and consumers would feel is low. On the other hand, the damage caused by monetary tightening amid stagnant demand for domestic products would be immeasurable.

What is very much concerning in the current monetary policy situation is the relationship between inflation, experience inflation rate and voting behavior. The price increases of daily commodities that are frequently purchased are readily felt by many consumers, while lower prices on durable consumer goods, cram schools and lessons and other services are less noticeable. Even companies often think that poor sales may be due to their business model, as opposed to rising costs that are clearly not their doing. The rise in daily commodity and material prices easily makes both households and companies think that “society is getting worse through no fault of our own.”

Rising prices of essential goods does not benefit anyone. On the other hand, it should also be noted that no matter how bad the economy is, not all people will be in danger of losing their jobs. In past economic theory, it was hypothesized that politicians tended to downplay inflation and emphasize the unemployment rate in order to win elections, which results in a stronger inflationary tendency. However, this assumption does not apply to modern developed countries, especially Japan. In elections, all voters only have one vote each to give. As a result, the ruling party turns a blind eye to the economy and the issue of workers in a situation where it is easy to lose your job, instead being incentivized to do everything in their power to contain the rise in resource, food and material prices, which is disliked by almost all voters.

Where to apply government spending

I am repeating myself, but looking at the CPI, Japan is currently far from experiencing inflation. Moreover, the price index of companies and producers with a high proportion of import goods increased by 9.7%, which is far below the 31.4% increase in the eurozone and not much different from the 10.3% increase in the United States (all in February compared to the same month of the previous year). From this, it can be seen that the yen’s depreciation is not the main cause of the price rise for corporate goods. The challenge for the Japanese economy is how to minimize the contraction of domestic economies in response to rising resources prices and other factors that cannot be controlled by the Japanese economy.

To ensure that the burden of high costs does not lead to a reduction in labor costs for companies, it is necessary to make it easy to pass on the cost increases to sales prices. In other words, it is necessary to make it easier for companies to raise prices. Ongoing monetary easing, specifically the low-level suppression of long-term interest rates, needs to continue until we see a clear rise in the inflation rate of domestic products.

In order to steadily advance this inflationary policy given the current circumstances, the government will need a considerable amount of courage. Inflation is a policy that is “broad and shallow” and is disliked by everyone.

However, if Japan were to resurrect the demons of deflation by prioritizing currying short-term favor with voters, the damage will be even worse than the COVID-19 shock or the Ukraine crisis. It will result in long-term losses to the Japanese economy.

Of course, supporting demand for domestic products is not driven solely by monetary policy. Fiscal policy is another important tool. Where do we want government spending to go? Pay attention to goods whose prices are currently rising. Oil, gas and wheat are all goods whose price formation the government is heavily involved in.

Promising candidates include the ongoing increases in subsidy amounts paid to each oil wholesaler and the trigger clause for gasoline provisional tariff rate that is popular in both the ruling and the opposition parties. Furthermore, electricity charges can be reduced by more than 10% by financial burdens and temporary suspension of levies for the promotion of renewable energy power generation. This is to say nothing of wheat, whose price is actively determined by the state as a rule. We ought not to spare fiscal resources to curb these individual prices.

Nuclear and coal-fired thermal power

Moreover, the present shock has made the world recognize the dangers of relying on overseas imports for a large part of energy and having imports from a narrow set of places in certain regions. In response to this, countries around the world are seeking to change their energy policy. Here, nuclear and coal-fired thermal power are garnering attention. Europe’s commitment to renewable energy has been based on a stable supply of the baseload electricity source of natural gas from Russia. Japan must also take seriously the fact that renewable energy is not a baseload electricity source and change its energy policy.

The first thing to consider is restarting the nuclear power plants. Nothing but public opinion stands in the way of allowing nuclear power plants to restart under enhanced safety standards. Public opinion is also changing in the wake of the recent surge in electricity prices. This is also a policy tool that can be implemented without a need for fiscal resources, a measure that should be given the highest priority.

It should also be noted that the energy efficiency of Japan’s coal-fired power generation is extremely high. By replacing old thermal power generation with new coal-fired power generation, we can reduce the total carbon dioxide emissions. Furthermore, coal carries low geopolitical risk due to the dispersion of its production areas. I believe the construction of new coal-fired power plants would be a great candidate for government spending in the medium term. We also must not forget that this growing focus on geopolitical risk in energy among countries can be an opportunity for Japan to spread its coal-fired power generation to Europe, forced to resume its coal-fired power generation in the future, as well as to developing and middle-income countries.

There is nothing the Japanese government can do directly to address the current surge in resources prices. The priority should be to minimize the contraction of domestic economies. This requires an expansion of government spending. Moreover, government spending in response to the current crisis is not merely a short-term economic support measure but is significant also as an investment to enhance our capacity to respond to similar crises in the future. Rather than fearing short-term financial burdens, we need proactive government spending to prevent future destabilization in Japan.

Translated from “Roshia no bokyo, Yuragu chitsujo—Ukuraina josei ijo no risuku toshite ‘Endaka taiboron ga maneku kiki’ (Russian Violence and a Shaken Order: A “Crisis from an Eagerly Awaited Yen Appreciation” Posing a Greater Risk than the Situation in Ukraine),” Chuo koron, June 2022, pp. 84–91. (Courtesy of Chuokoron Shinsha) [July 2022]

Keywords

- Iida Yasuyuki

- Meiji University

- Russia

- Ukraine

- COVID-19

- yen appreciation

- depreciation

- exchange rate

- real exchange rate

- energy prices

- oil price

- wheat price

- resources prices

- consumer price

- CPI

- inflation

- deflation

- economic policy

- terms of trade

- nuclear power

- coal-fired power generation