Challenge for IPEF: Reflection of IPEF Outcomes in Existing Trade Agreements

On May 23, 2022, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, U.S. President Joseph Biden, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and summit-level and cabinet-level representatives from 10 other countries attended a meeting on the launch of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) in a hybrid format in Tokyo.

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Mukunoki Hiroshi, Professor, Gakushuin University

Key points

- Doubts over the effectiveness of any rules or agreement reached under the IPEF

- Expectations for the IPEF as a bridge connecting different cooperation frameworks

- Opportunity for discussion of export restrictions, which existing trade agreements leave untouched

Prof. Mukunoki Hiroshi

With the global economy facing a myriad of risks and with the emphasis being put on economic security, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is attracting attention as a new opportunity for international economic cooperation among nations.

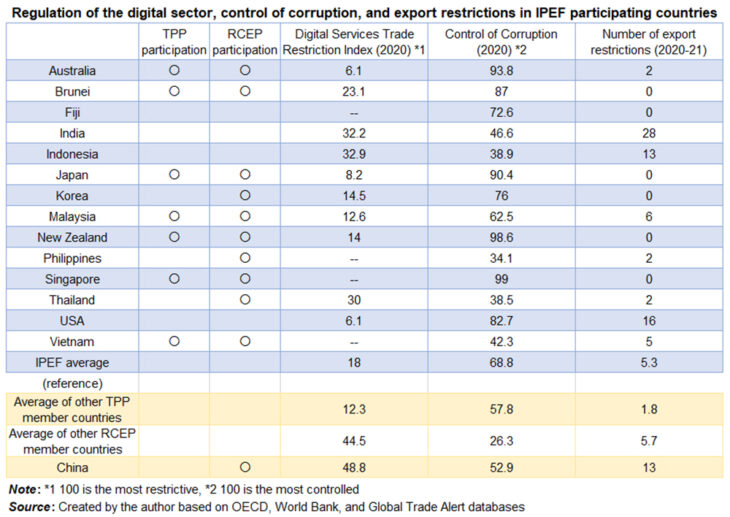

The IPEF was proposed by President Biden in May. It is a mechanism to build international cooperation, focusing on four pillars: trade; supply chains; clean energy, decarbonization and infrastructure; tax and anti-corruption. Fourteen countries, including Japan, South Korea, India, as well as countries from Southeast Asia and Oceania, have agreed to join (see Table).

Whilst the United States has seen its presence in the international cooperation arena weaken with its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), China is strengthening its economic ties with various countries by advancing its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), becoming a signatory of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) and applying to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The underlying purpose of the IPEF is to form a new economic trade bloc under the leadership of the United States whilst pushing back against China.

The IPEF includes other countries besides the United States that have left existing cooperation frameworks, such as India which exited from the RCEP. The IPEF is hugely significant in that it creates an opportunity for fresh dialogue in the Indo-Pacific Region. The details are still unclear, but on the trade pillar, the IPEF is expected to pave the way for rules on the digital economy, and the fact that the four pillars comprehensively cover global economic issues is also something to be welcomed.

The table shows a comparison of the strictness of rules on the digital economy in IPEF participating countries based on the “Digital Services Trade Restriction Index” developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). It indicates that, overall, rules are not strict; however, there are some participating countries with comparatively strict rules such as India, Indonesia, and Thailand. A comparison based on the “Control of Corruption” index published by the World Bank also shows significant variation among participating countries.

Existing trade agreements do not necessarily deal with such areas. If progress was made through the IPEF on the development of rules on the digital economy or on anticorruption through mutual supervision, this would be a major outcome.

However, the proposed mechanism of the IPEF is significantly different from existing frameworks. In multilateral trade negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and negotiations of free trade agreements (FTAs) and economic partnership agreements (EPAs), including the TPP and the RCEP, participants have sought comprehensive economic cooperation by setting legally binding rules in various areas in addition to mutual tariff reductions.

On the other hand, cooperation on tariffs is not specifically covered by the IPEF. Furthermore, participating countries do not need to focus on all four pillars and can participate in negotiations in selected areas. The IPEF is likely to be a framework for exploring soft cooperation through the establishment of common targets.

Consequently, the barriers to entry are low and the number of participating countries is expected to grow. Since only willing countries will be involved in negotiations on each pillar, conflicts of interest are also unlikely to arise. The approach of implementing elements sequentially as outcomes are generated offers flexibility. That said, if countries grappling with issues on each pillar are reluctant to participate in negotiations, the outcomes will be limited. Since the IPEF is not a legally binding agreement requiring congressional approval, there is doubt over the effectiveness of any rules and agreements established under it.

Given that there is no legal basis, the introduction of penalties will probably be difficult. Even if they are introduced, they will diminish the IPEF’s advantage in facilitating countries’ participation in negotiations. The IPEF is unlikely to replace the hard comprehensive trade agreements that already exist.

If anything, the IPEF should be seen as a supplementary initiative and an opportunity to strengthen and update existing trade agreements. With WTO negotiations in deadlock in the early 2000s, nations rapidly sought trade cooperation by signing bilateral FTAs and expanding customs unions such as the EU. On the downside, this profusion of trade agreements with different rules became an obstacle to supply chain diversification.

Subsequently, region-wide FTAs such as the TPP and RCEP began to be signed, encouraging the development of more extensive supply chains and enabling the establishment of standardized rules. That said, a large number of participating countries made negotiations difficult, causing key countries to exit the agreements.

The IPEF could potentially serve as a bridge connecting different cooperation frameworks. Participating countries should not only aim to realize the rules and ideas developed under the IPEF but should also explore a way to realize them in a way that is legally binding, albeit only partially by incorporating them into revisions of existing trade agreements. This would enhance the effectiveness of agreements under the IPEF and lead to their application to non-IPEF participating countries.

◇ ◇

TPP member countries that have not agreed to join the IPEF have less digital regulation than participating countries (see Table), and there is not much of a difference between members and non-members in terms of control of corruption. Accordingly, it indicates that outcomes under the IPEF in these areas could also be applied to other TPP member countries comparatively easily

Conversely, rules on electronic commerce and anti-corruption established under the TPP, along with the content of the environment chapter that promotes mutually supportive trade and environmental policies, could also conceivably be useful for IPEF negotiations. Reconciliation of the IPEF with existing agreements will encourage the United States to return to the TPP and new members to join and will also help expand region-wide FTAs.

However, China and RCEP member countries not participating in the IPEF have stricter digital regulation than IPEF participating countries and also have much less corruption control, making reconciliation more difficult. That said, 11 out of 15 RCEP member countries are participating in the IPEF, providing a basis for reconciliation between the two.

Furthermore, the four pillars are interrelated and the IPEF should ideally restrict participating countries to some extent from “cherry-picking” what they like in these pillars. One of the effective ways to build more diverse and resilient supply chains is to reduce procurement risks and diversify suppliers by increasing the quality of systems including anticorruption. Meanwhile, tariff cooperation is helpful for decarbonization. According to research by Joseph S. Shapiro, Associate Professor at the University of California Berkeley, the existing import tariffs and non-tariff barriers are substantially lower on dirty than on clean industries, where an industry’s “dirtiness” is defined as its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per dollar of output. Efforts to discuss measures for liberalizing the trade of clean goods and preventing imports of dirty goods as part of IPEF negotiations will no doubt contribute to decarbonization.

Initiatives to address export restrictions are also important. Looking at the number of times export restrictions were introduced in 2020–2021 before the sanctions against Russia, specific IPEF participating countries have introduced export restrictions many times (see Table). Export restrictions on key commodities are a cause of supply chain disruptions and also lead to inflation around the world. The rules on export restrictions in existing trade agreements do not go far enough and the IPEF should be used as an opportunity for more in-depth discussion.

The IPEF is based on antagonism towards China but this initiative must not be something that fans antagonism between nations. As a mechanism for soft cooperation, the IPEF should be an opportunity for non-exclusive dialogue.

Unlike the United States, Japan is in both the TPP, which China has applied to join, and the RCEP, which includes China. Leveraging this position, Japan has an important role to play in encouraging China and other foreign nations to abandon digital protectionism, control corruption, and rein in export restrictions whilst seeking reconciliation between the IPEF and existing trade agreements.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 4 August 2022 under the title, “IPEF goi heno kadai (II): Kison no boekikyotei ni seika hanei (Challenges for the IPEF Agreement (II): Reflection of Results in Existing Trade Agreements).” The Nikkei, 4 August 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Mukunoki Hiroshi

- Gakushuin University

- Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

- IPEF

- economic cooperation

- trade

- supply chains

- clean energy

- tax

- anti-corruption

- electronic commerce

- tariff cooperation

- export restrictions

- Trans-Pacific Partnership

- TPP

- Belt and Road Initiative

- BRI

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

- RCEP

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- OECD