Ishibashi Tanzan and the Significance of International Cooperation: The Importance of Designing Systems to Support Ideals

Ishibashi Tanzan (1884–1973)

Source: Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures

(https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/)

Makino Kuniaki, Professor, Keio University

Key points

- Emphasis on international division of labor rather than securing colonies

- Lofty Anglo-American ideals severely criticized as deception in Japan

- Demonstrate benefits of liberalization to avoid a crisis in the international order

Prof. Makino Kuniaki

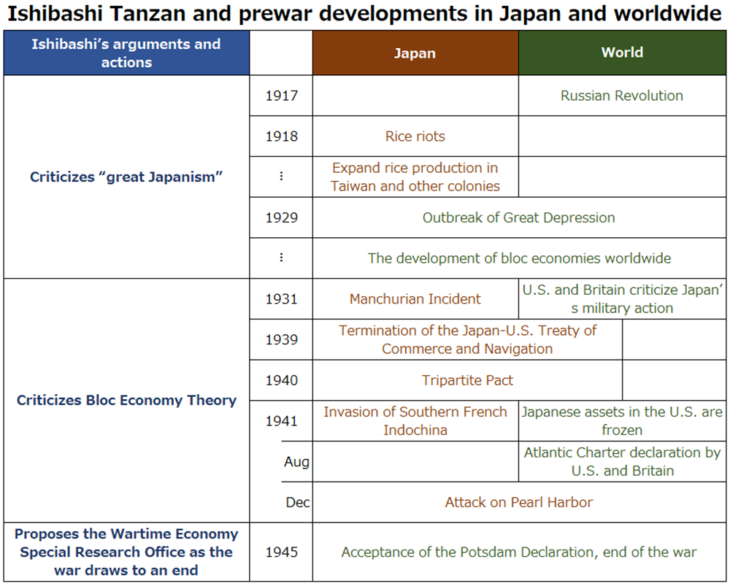

Ishibashi Tanzan (1884–1973), the economist who played a role in the gold embargo controversy in the early Showa period, turned to politics after the war and became prime minister. He is known for his criticism of the “great Japanism” that aimed to acquire colonies in the Taisho period (1912–1926) and for championing the so-called “little Japanism.”

The ideas that Ishibashi developed based on his research of classical economics in Britain, including Adam Smith and David Ricardo, provided the context for his arguments. According to Ishibashi, the source of wealth is found in labor and the economy is based on the division of labor among free individuals. He also believed that to develop the economy, all countries, not only Japan, should enhance the skill sets of their respective nationals through education to increase labor productivity, and that the international division of labor should be promoted through trade to broaden the scope of labor division.

Consequently, Japan’s “surplus population,” viewed as problematic at the time, would instead be an advantage for economic development based on the division of labor. Even if Japan has no natural resources, this does not pose a problem from the perspective of the international division of labor as long as peace is maintained and trade is conducted freely. Today, Ishibashi is highly acclaimed for the foresight of his argument for peaceful economic development, arguing as he did that trying to secure and maintain colonies would require large military expenditure, and that Japan could obtain far more advantages through trade even if Korea and Taiwan and other colonies were abandoned.

However, being alive today, we know that prewar Japan headed in the opposite direction from Ishibashi’s arguments. Why is that?

The utilitarian claim that colonies are not profitable can be reversed to say that profitable colonies are good. In response to the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Rice Riots (popular uprisings against high rice prices) of 1918, the goal was to provide a stable supply of rice for the urban population, but rather than importing rice, rice production was expanded in the colonies of Taiwan and Korea when the international balance of payments deteriorated after World War I.

As a result, Japan achieved rice self-sufficiency by the 1930s, but this also meant that Taiwan and Korea became indispensable to the stability of Japanese society. Investment in Manchukuo, the state created in 1932, as well as the increase in exports following the decline in the exchange rate caused by the expansionary fiscal policy and reimposition of the gold embargo implemented under finance minister Takahashi Korekiyo (1854–1936) contributed to Japan’s economic rebound after the Showa Depression (1929–30). Contrary to Ishibashi’s arguments, Japan benefited from its control of Taiwan, Korea and Manchukuo.

This experience of success also led to the North China Buffer State Strategy, which was an attempt to place North China under Japanese control. This further aggravated relations between Japan and China, leading to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45).

Meanwhile, the rapid increase in exports from Japan after the Showa Depression caused severe trade friction with Britain, in particular. To protect its valuable markets, Britain sought to strengthen the sterling bloc. In Japan, the national public opinion, including both the military authorities and the financial circles, argued for building a “Manchukuo-Japan economic bloc” and, with the addition of China, a “Japan-Manchukuo-China economic bloc.”

Ideologically close to Ishibashi, the economist Takahashi Kamekichi (1891–1977) came to criticize Britain, which had always argued for free trade, for switching to a bloc economy, and cooperated with the military authorities by arguing for the creation of the Japan-Manchukuo-China economic bloc. Even though Ishibashi accepted the hard facts behind Japan’s actions, he maintained his basic ideas and continued to argue for improving relations with Britain and to stress the importance of international trade while criticizing bloc economic theory, but he was unable to change the course of events.

In Japan, the attitudes of Britain, which talked about free trade or bloc economy depending on the situation, and the United States, which limited Japanese migration while professing to be a free country, were regarded as hypocritical, and the prevailing mood was for have-not Japan to challenge the international order of the haves centered on Britain and the United States.

This mood grew stronger when the United States implemented economic sanctions to curb Japan’s military actions. In September 1940, Japan concluded the Tripartite Pact with the intention of opposing the United States, and also occupied Northern French Indochina.

World War II had already begun and the United States, which had strengthened its stance in support of Britain, decided to impose an export ban on scrap iron to Japan to further rein in Japan, which had allied itself with Germany. As it became difficult for Japan to obtain resources, the arguments for the Nanshin-ron (Southward Advance Policy) to expand into Southeast Asia to secure resources grew stronger. Japan invaded Southern French Indochina in July 1941, but the United States immediately froze all Japanese assets in the U.S. and suspended oil exports, as did Britain.

Shortly after, on August 14, the Atlantic Charter (referred to as the “Anglo-American joint declaration” in Japan at the time) was jointly released by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill following their meeting. In economic terms, the Atlantic Charter extolled the importance of free trade, economic cooperation, freedom from fear and want, and freedom of the seas. In particular, the Charter specified efforts “to further the enjoyment by all states, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.”

The Atlantic Charter became the foundation for the subsequent international order based on the United Nations, but there was a strong backlash in Japan, which regarded the principles adopted by the United States and Britain in the immediate aftermath of economic sanctions as a form of deception and did not take them seriously. The economic sanctions imposed by Britain and the United States in an attempt to restrain the actions of the Japanese military had the opposite effect of driving home the gap with these principles. Japan entered the Pacific War to solve the practical problem of securing oil, and to build the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to counter the international order centered on Britain and the United States.

Meanwhile, even before the war started, Ishibashi had been stressing the importance of looking to the future and thinking about the period after the war. At Ishibashi’s suggestion, the Ministry of Finance set up the Wartime Economy Special Research Office as the war was drawing to a close. In addition to Ishibashi, economists and financial experts served on the committee to conduct research on the postwar period. The committee discussed the preferred world order while studying the Bretton Woods Agreement issued by the Allied side.

During the discussions with the Committee members, Ishibashi argued that even if its territory was limited to the mainland only, postwar Japan could develop fully by focusing on domestic development and taking advantage of the restoration of free trade in the world based on the international order. After the war, the economist Nakayama Ichiro (1898–1980), who served on the committee, was a great admirer of Ishibashi for his foresight.

The postwar Bretton Woods system = General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)/ International Monetary Fund (IMF) system was created based on the realization that bloc economies had caused World War II. Ishibashi’s foresight became the focus of attention when the principle of free trade was secured by the system and many countries, including Japan, profited and actually achieved growth under the system.

Even if the ideals are lofty and the ideas are superior from a logical viewpoint, people will be disappointed and reject those ideas and ideals if the systems for implementing them do not function well and people see no advantage in abiding by them. Today, the liberalization of trade and investment is progressing and the globalization of capitalism is advancing, but the international order is in a critical situation due to the actions of countries and people who do not see the benefits.

As well as reexamining Ishibashi’s ideas on the importance of free economic activity, it is now a pressing issue to think about what kind of system should be designed to realize these ideas and to spread the benefits to many people and countries.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 15 August 2022 under the title, “Ishibashi Tanzan ni manabu Kokusaikyocho no Igi: Rinen sasaeru Seido no Sekkei Kanyo (Ishibashi Tanzan and the Significance of International Cooperation: The Importance of Designing Systems to Support Ideals).” The Nikkei, 15 August 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Makino Kuniaki

- Keio University

- Ishibashi Tanzan

- economics

- international cooperation

- ideals

- division of labor

- trade

- investment

- liberalization

- international order

- great Japanism

- little Japanism

- colonies

- Manchukuo

- Britain

- United States

- World War II

- Bretton Woods Agreement

- GATT

- IMF