Markets calm, but loss of liquidity will lead to financial crisis starting with nonbanks—The S&L crisis has proven that risks cannot be ignored even if the asset size is small

“On April 4, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a report saying that vulnerability in the nonbanks sector is coming to a head. The report points out that the NBFI have now grown into a major force, holding 49% of the world’s financial assets, and refers to their potential to influence international financial stability.”

Photo: fizkes / PIXTA

Otsuki Nana, Senior Fellow at Pictet Japan

The international credit unease that has spread rapidly since the beginning of March is showing signs of quieting down, the last instance being the Credit Suisse bailout by UBS. There has been some praise for the response from the relevant national authorities, which successfully checked the spread of further unease, but on the other hand, many issues pertaining to the state of financial regulations for liquidity and capital, as well as the handling of banking bailouts, have been exposed. Once again, there is need for a debate on how best to stabilize the financial system. If the supply of liquidity from banks stagnates going forward, the possibility of a new financial crisis with its epicenter in nonbanks, or other entities that are not covered by bailout measures, is not zero.

Unprecedented turmoil around the credit unease drama

The series of dramas around credit unease that started with the bankruptcy of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was striking for the speed at which liquidity and capital concerns spread. This was different from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

As of the end of December 2022, the Tier 1 common equity ratio at SVB was 12.1% (on a consolidated basis), which is well above the industry average of 9.7%. Even so, rumors of weaknesses at SVB started up in early March. On March 8, the bank contained the rumors by presenting a plan to increase capital at SVB, but a mere two days later, on March 10, the bank was driven to bankruptcy. What should have been an effort to provide reassurance for financial aspects through an injection of capital ended up multiplying concerns about financial aspects.

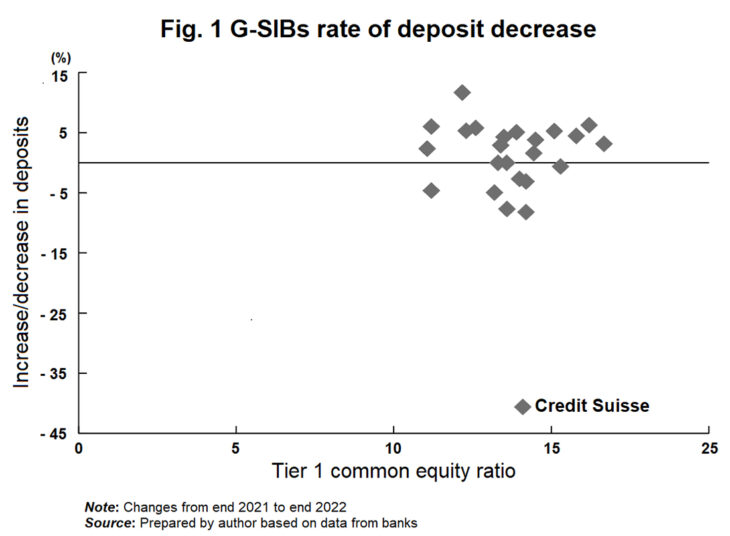

Credit Suisse (CS) differs from SVB in terms of both business category and region, but market concerns about liquidity forced the bank into a rescue merger with UBS. In the past, financial difficulties at major banks have mostly been caused by bad loans, bond losses, capital shortages, and other balance sheet problems. Although such problems had been flagged up at CS in the past, there were no major differences with other Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) apart from a recent decrease in the rate of deposits (Fig. 1). On March 15, the Swiss financial authorities announced their intention to provide CS with liquidity support, but the turmoil on the markets continued. On March 19, a rescue deal was agreed with UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank.

Financial regulations did not function despite having been strengthened

After the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), liquidity regulations and the Capital Adequacy Ratio were strengthened through the Basel 3 framework to stabilize the financial system. In view of the current turmoil, however, it is difficult to claim that these regulations have functioned as originally intended. Rather, it cannot be denied that by signaling movement to secure liquidity and capital, the banks instead stirred up anxious mindsets on the markets with unexpected consequences. There is room for further discussion regarding the nature of such financial regulations.

The debate about the full write-off of the AT1 bonds held by CS is likely to heat up. AT1 bonds are also referred to as “bail-in bonds.” It is a mechanism to enhance capital by canceling debt, including principal reduction, in cases where the equity capital ratio is below a certain level, or the authorities recognize risk of bankruptcy.

In the CS rescue measures, the value (despite depreciation) was not set to zero for CS shareholders, whose shares were exchanged for UBS shares, whereas the value of the bonds, which should be at the top of the repayment hierarchy, was first reduced to zero. Since the relevant matters are included in the contract clauses, this process is not a breach of contract. However, with regard to consistency around equities and bonds when resolving bankruptcies, stakeholders issuing similar bonds will have to hold serious discussions without limiting talks to the current problems at CS.

Optimism is spreading, but the fires are still smoldering

Meanwhile, some market stakeholders have started to express the view that there is no need to be so pessimistic since the character of the situation is completely different from the GFC. Some US banks that have seen their share price fall to one tenth of what it was before the turmoil will not recover the value easily, but all of these banks have assets equal to or lower than SVB.

This is not comparable to Lehman Brothers, which had huge amounts of off-balance sheet transactions and a balance sheet on a scale close to 70 trillion yen. In addition, the US authorities have announced that they will provide guarantees in excess of the upper limit of deposit insurance for SVB and signature banks. Even if something were to happen at a larger bank, there is a strong possibility that the government will protect creditors, and the prevailing mood is that a further outflow of deposits is unlikely.

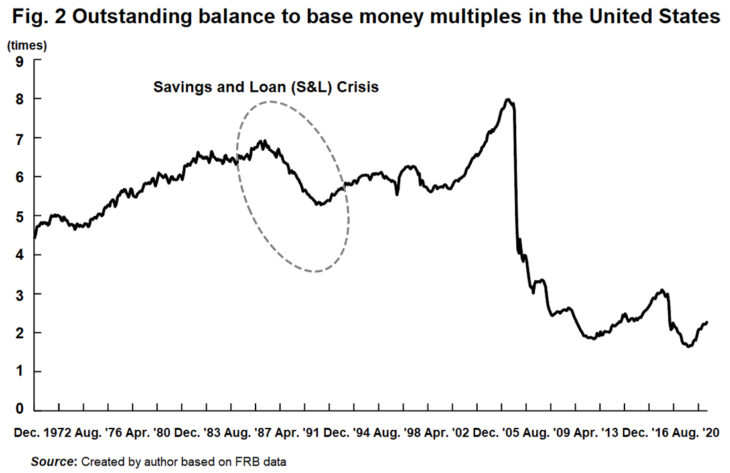

Nonetheless, even if, for argument’s sake, there are no major shocks, there are other possible risks along the lines of the S&L (Savings and Loan Association) crisis-type financial instability that occurred in the 1980s. More than a thousand savings and loan associations failed during the S&L crisis. Even though they were all small in scale, it took nearly ten years before the situation was brought under control and it had significant impact on the subsequent economy, including the continued moderate decline in the bank loan balance as a multiple of base money (Fig. 2). We must not ignore something simply because the scale is small.

Will the next epicenter be nonbanks?

The view among market stakeholders is that a major shock would be better because the market would bounce back quickly. Such a shock scenario is undeniable at present. But assuming there is a shock, would it not come when the turmoil hits an area that cannot be rescued to the same extent?

At the time of the GFC, there were no options to rescue investment banks at the taxpayer’s expense. This is because there was a “norm” (social common sense) that high-earning investment banks who were risk-takers could not be rescued.

The same was true of the financial turmoil in Japan in the late 1990s. After Yamaichi Securities voluntarily wound up its business, the markets were shaken by the bankruptcy of noted banks such as the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan and the Nippon Credit Bank. At the time, bankers were high income earners and it was politically difficult to spend hard-earned tax money on a bailout. However, as a result, the availability of credit at Japanese banks shrank significantly. When a Japan premium was imposed on foreign currency procurement, it became difficult to run overseas operations, which was a major factor in Japan’s prolonged economic recession.

Is it possible that such developments are coming our way in the future? Assuming, as already mentioned, that rescue measures will be taken where major banks are concerned, the problem will be in areas outside the scope of banking regulations. For example, Non-Bank Financial Intermediation (NBFI) or crypto-asset managers and start-ups.

Among these, I would like to pay close attention to the trends in NBFI, formerly ridiculed as “shadow banking.” On April 4, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a report saying that vulnerability in the nonbanks sector is coming to a head. The report points out that the NBFI have now grown into a major force, holding 49% of the world’s financial assets, and refers to their potential to influence international financial stability.

In the near term, the rapid rise in interest rates is making the earnings environment for banks tougher as countries have continued to quickly raise interest rates due to the credit squeeze. Unless the NBFI also create credit, they will have no depositors and there will be little ground for a bailout with public money. The possibility that the supply of liquidity from banks to nonbanks will stagnate, leading to a financial crisis focused on the NBFI, is definitely not zero.

Translated from Shijo wa fuan ippukumo, ryudosei ga ushinawareruto non-banku-hatsu kinyu kiki e (Verify! Echoes of credit unease at US and European banks: Markets calm, but loss of liquidity will lead to financial crisis starting with nonbanks—The S&L crisis has proven that risks cannot be ignored even if the asset size is small) Shukan Kinyu Zaisei Jijo, April 18, 2023, pp. 27–29 (Courtesy of KINZAI Institute for Financial Affairs, Inc.) [June 2023]

Keywords

- Otsuki Nana

- Pictet Japan

- Graduate School of Management

- NUCB Business School

- financial system

- financial crisis

- credit unease

- Credit Suisse bailout

- UBS

- nonbanks

- Silicon Valley Bank

- US banks

- European banks

- Global Systemically Important Banks

- Global Financial Crisis

- AT1 bonds

- bail-in bonds

- Non-Bank Financial Intermediation

- “shadow banking”

- interest rates