The focus is on the “security exception” provision in trade; Distance from China

Regarding China, the G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué in May 2023 said, “We are not decoupling or turning inwards. At the same time, we recognize that economic resilience requires de-risking and diversifying. We will take steps, individually and collectively, to invest in our own economic vibrancy.”

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Key points

- High risk of legal instability and unpredictability

- Economic coercion negating the advantages of free trade

- Making rules to correct adverse effects of system differences

WATANABE Mariko, Professor, Gakushuin University

At the G7 Hiroshima Summit in May, there was a directional shift from “decoupling” to “de-risking” in relations with China.

The term “de-risking” was proposed by Ursula von der Leyen, President of the EU, but similar views were expressed in statements by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen.

In a speech in April, Yellen presented three principles of economic China policy: (1) first of all, securing the national security interests of the United States, allies, and partners as well as protecting human rights, (2) otherwise, fair and healthy economic competition with China, and (3) cooperation on global challenges. Sullivan said that “Export controls are also limited to narrow technical areas that influence the military balance, and we are not trying to cut ties with China.”

I feel that this direction was reflected already in the strict semiconductor regulations on China announced by the United States in October 2022. The US banned exports of semiconductors and related equipment for servers to China and from working for Chinese semiconductor companies. Currently, it is difficult for China to build cutting-edge servers on its own. At the same time, semiconductors for smartphones and autonomous driving were not subject to any restrictions.

The technologies that constitute computing power may be diverted to military uses. Since there are currently no agreements in this field, they are likely judging that export controls can be implemented in the same way as for military technologies. The US stance on China seems to have returned to the classic “trade management to ensure national security.”

Meanwhile, it is suggested that if a US company in receipt of subsidies invests in China, that will lead to a suspension of those subsidies in addition to other disciplinary measures. This may contradict Yellen’s intentions regarding fair and healthy economic competition. Is American China policy looking to achieve a compromise between corporations in possession of technologies, military concerns, and political concerns?

◇◇◇ ◇◇◇

So, what is the exact “risk” that “derisking” is confronting? I believe it is the legal instability and unpredictability stemming from China’s “unique system,” which might skew dealings with China in a unilateral way.

China has a state system where only the Communist Party holds the power to enact the constitution, and as a result, politics transcend law. The ongoing “rule by law” in China means “governance of society by law,” not a mechanism where the law restricts power. Thus, there is a significant mismatch between how the law operates inside China and outside, which could be a potential source of friction.

China’s basic economic system, the socialist market economy, unlike the state monopoly capitalism targeted by the communist bloc during the Cold War era, has encouraged robust competition between companies. However, under the principle of “prioritizing state ownership in the economy without hindering the development of private enterprises,” companies are discriminated against based on ownership. Furthermore, their treatment is unstable, fluctuating with the political climate.

Under this system, the Xi Jinping administration prioritizes “national security” and has broadly defined its scope. This could lead to a broad interpretation of clauses that allow for exceptional treatment on the grounds of security in trade rules. This too can be a source of major friction with outside systems.

Specifically, actions like imposing high tariffs on Australian barley and wine, quarantine measures against Taiwan’s pineapples, and refusing customs clearance for Lithuanian products are evident. If such actions are seen to lack general justification and target specific countries, they violate World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Moreover, if economic coercion is perceived as being linked to political intent, disciplines stipulating that the benefits of free trade under trade rules cannot be enjoyed are necessary.

China has yet to join the Government Procurement Agreement, which it had promised to do quickly upon joining the WTO in 2001. While a directive set in October 2021 advocates non-discrimination between domestic companies and foreign-invested companies in China, it discriminates against imported products. It doesn’t meet the standard demanded by the WTO Government Procurement Agreement, making it questionable if they can adhere to the government procurement chapter of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which China has applied to join.

On foreign company investments in China, right after the WTO accession, foreign companies responded to demands from Chinese companies to introduce specific technologies in exchange for market access and technology. However, administrative demands for this should be prohibited, and the TPP’s investment chapter bans it.

There are also concerns in the digital and competition law worlds. Especially in the realm of competition law, where international rules are not yet well-established, there have been cases where China makes excessive demands that could infringe on the benefits of other countries. A rule demanding non-distortionary use of administrative powers is essential.

If administrations excessively prioritize their own countries under the guise of ensuring their national security, other countries can’t ensure the safety of economic transactions under free trade. Indeed, revisions to the counter-espionage law have raised significant concerns in the business world. If a country repeatedly acts without gaining consent from other nations based on their own interpretation, it is necessary to embed in the rules that they cannot enjoy the benefits of free trade under trade regulations.

◇◇◇ ◇◇◇

On the other hand, when pushing for de-risking towards China, if the discussion revolves around differences in values and systems, there’s no way out.

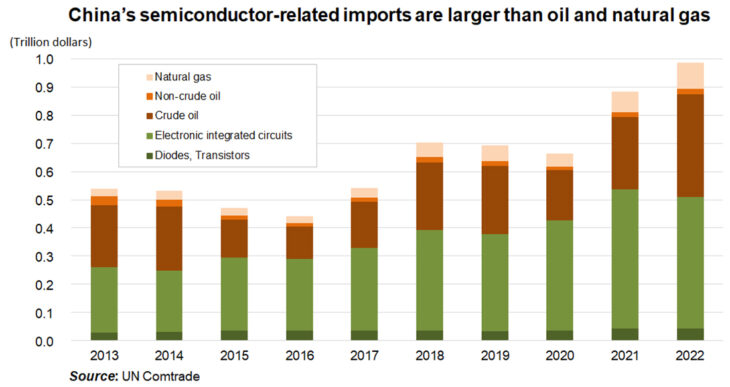

Chinese imports of semiconductor-related products exceed those of natural gas and oil, whose production within China is limited (see figure). China is firmly embedded in global relations in the economic sphere, which is a “substructure.”

If the difference in systems unilaterally poses concerns of harm, it should be subject to rules and disciplined accordingly.

At this juncture, it is imperative to specify to what extent exceptional actions based on security reasons are permitted.

Precedents related to security exceptions under existing WTO rules have been accumulating. Additionally, while the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in East Asia, of which China already is a member, allows countries to define their own security exceptions, the CPTPP obligates member countries to explain their justifications. A process to visualize the boundaries of security exceptions in the world of trade rules is likely necessary to clarify to what extent China’s “national security first” approach can be accepted by other countries.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 4 July 2023 under the title, “Chugoku tono kyorikan (I): Tsusho no ‘Anpo reigai’ kitei ga shoten (A Sense of Distance from China: With a Focus on “Security Exception” Clauses in Trade).” The Nikkei, 4 July, 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Watanabe Mariko

- Gakushuin University

- China

- US

- China policy

- economic coercion

- free trade

- decoupling

- de-risking

- Ursula von der Leyen

- Jake Sullivan

- Janet L. Yellen

- national security

- human rights

- export controls

- military technologies

- semiconductor regulations

- rule by law

- competition law

- security exceptions

- WTO rules