Reconsidering Safety Nets: Making Universal Basic Services Free

“According to a Cabinet Office survey, more than 90% of the public considers themselves to be middle-class. However, the meaning of this all-Japanese-are-middle-class mentality has changed, with today’s middle class maintaining a normal lifestyle only by giving up marriage, childbirth, home ownership, and consumption.”

Photo: Ryuji / PIXTA

Key points

- Not only low-income earners, but also the middle class has serious worries about the future

- Mechanisms for “not creating vulnerable people” anywhere in the whole population

- It is necessary to balance benefits and burdens, e.g., by raising the consumption tax rate

Ide Eisaku, professor, Keio University

Times of crisis destabilize the lives of not just the majority but also the few. Also the COVID-19 crisis brought to the fore how low-income earners were suffering from “anxiety about tomorrow” while the middle class were suffering from “anxiety about the future.” Post-COVID safety nets need to rationally resolve these two anxieties both economically and politically.

The term “safety net” generally conjures up an image of relief for people struggling to make ends meet. Yet the number of people struggling with this is growing, with the middle class now starting to feel the pressure as well. Since the late 1990s, the standard [household] model has become dual-income households, but the incomes of working households [nonetheless] peaked in 1997. Households with incomes of less than 3 million yen account for 34% of the total, while households with incomes of less than 4 million yen account for 47%, bringing us back to 1989 levels.

Spending on food and drink, clothing, accommodation, and education remained unchanged or decreased during the Heisei period (1989–2018), with the homeownership rate also declining. According to a Cabinet Office survey, more than 90% of the public considers themselves to be middle-class. However, the meaning of this all-Japanese-are-middle-class mentality has changed, with today’s middle class maintaining a normal lifestyle only by giving up marriage, childbirth, home ownership, and consumption.

As people have no choice but to protect their own livelihoods, they lose interest in the lives and hardships of others. According to the International Social Survey Programme, Japan ranks first among 35 countries and regions in terms of the percentage of people who do not believe that the government is responsible for providing healthcare for the sick or assistance for the elderly, university students from poor households, and those unable to secure housing. Japan truly is a divided society.

◆◆◆ ◆◆◆

Is there any opening? Despite the intolerance of those struggling to make ends meet, about 80% of Japanese respondents in the World Value Survey agreed with the statement “The government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for.”

From partial relief to total coverage. It is based on this philosophy that I have promoted a policy of freely providing all citizens with universal basic services, including education, healthcare, nursing care, and welfare for the disabled, which are foundational for human survival and living. This means transforming society so as to provide for everyone.

Making universal basic services free will change “helping the vulnerable” to “not allowing anyone to be vulnerable.” If healthcare becomes free, this will remove the need for medical assistance, which accounts for more than 40% of public assistance.

Making nursing care and education free will remove the need for nursing care assistance, educational assistance, school attendance assistance, and so on. The stigma of relief will disappear, and society will change into one where everyone uses services as a right and where dignity belongs to everyone. Of course, there will still be those who need income security, such as the elderly, persons with disabilities, and single-parent households. Support for them should be a “decent minimum” rather than a minimal measure. This will include enhancing living assistance and unemployment benefits as well as introducing permanent housing benefits.

Please note my use of the word “security.” If even one half of a high-income power couple loses their job, the couple’s annual income will plummet, making it difficult for them to cover education costs and mortgage. In Japan, self-payment makes up a large part rather than being covered by public insurance. As such, losing your job is an especially big risk for anyone. A decent minimum is a way to deal with such common risks and not a fixed protection measure for people who have difficulties working. The middle class, which has been callous to those struggling to make ends meet, will be liberated from worries about the future through universal basic services and a decent minimum. Moreover, everyone becomes a beneficiary, eliminating suspicions about fraudulent payouts. While helping to remove social divisions, the same security that the middle class enjoy is also extended to the [low-income] earners who worry about what tomorrow may bring.

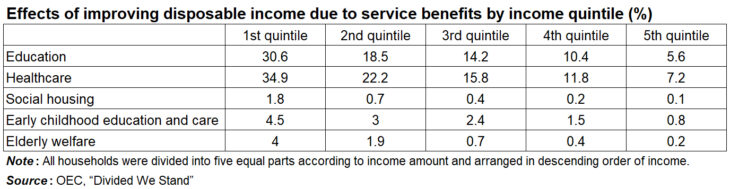

Once the middle class’s worries about the future are dispelled, huge deposits and savings will be diverted to consumption and investment, thus boosting the potential growth rate. Free services also increase the disposable income of low-income earners more than for high-income earners (see table). Adding a decent minimum to this will dramatically decrease economic inequality. With universal basic services and a decent minimum as the twin wheels, it will be possible to boldly guarantee both survival and livelihood. This is what I call the “life security concept.”

◆◆◆ ◆◆◆

The 2020 special cash payments offer ample insights. These cash payments of 100,000 yen necessitated a total budget of 13 trillion yen but making kindergartens and childcare centers free in 2019 only needed about 800 billion yen. Unlike universal basic income-type cash transfers, which go to all citizens, medical care, education, and other universal basic services can keep costs down.

Let us rearrange the 13 trillion yen spent on special cash payments based on the idea of life security. (1) Make university education, nursing care, and welfare for persons with disabilities free for all citizens as well as reduce the part of medical costs to be borne by the working generation to 20%. (2) Establish a housing allowance of 20,000 yen per month for 12 million households, which corresponds to 20% of all households. (3) Increase unemployment benefits by 50,000 yen per month from the current level.

This will drastically reduce the cost of living for the middle class and supply 840,000 yen per person per year to those who have employment difficulties. Life security would efficiently meet social needs by focusing on low-cost service benefits and ensuring that cash transfers mainly go to those with employment difficulties.

The issue is with financial resources. The bottom line is that if the consumption tax is raised by another 6%, it will be possible to not only provide free childcare for one year and free university for low-income earners but also to make medical care, nursing care, and university education for the middle class and above free. Moreover, school lunches, school supplies, and school trips for compulsory education can also be made free, while the salaries of nurses, caregivers, and childcare workers are raised. Of course, it is not necessary to limit this to consumption tax. However, while a consumption tax increase of 1% will generate tax revenue of 2.8 trillion yen, data from the late 2010s suggest that increasing the income tax for incomes over 12.37 million yen by 1%, tax revenue will only yield about 140 billion yen. Even if the corporate tax is raised by 1%, the tax revenue will only be about 500–600 billion yen. A realistic option would be to ensure fiscal fairness by appropriately combining income and corporate tax increases while making consumption tax the main focus.

We have curbed the tax burden by saving for the future. Because of this, even if the burden is increased as described above, the national burden ratio will remain more or less average compared to other major developed countries. Moreover, you cannot necessarily call this a burden increase. The reason is that everyone has been covering university tuition, medical costs, and nursing care in exchange for low taxes, so from a macro perspective, we are simply replacing self-payment with taxes. Yet society changes. Once reborn as a society of solidarity and mutual assistance, peace of mind about the future will serve as a springboard for better competitiveness and growth.

We have seen a trend since the COVID-19 crisis toward the universalization of benefits, with more and more action being taken to remove income restrictions. These are positive changes from where I stand, since I value the idea of security, but universalization without a plan for securing financial resources is no different from reckless spending.

The current fiscal debate assumes a binary choice between laissez-faire fiscal measures to combat high prices and austerity measures to avoid a fiscal crisis. Yet the fundamental middle ground between the two is a “principle of necessary sufficiency.” In a parliamentary democracy, we should identify societal needs and debate what burden should be placed on whom through what taxes. The role of public finance is to consolidate society by identifying and responsibly fulfilling needs. Laissez-faire fiscal policy that lacks an idea about how to secure financial resources and austerity that neglects needs are only quantitatively different, both failing to understand the essence of public finance.

We can pursue social justice by frankly inquiring about how to balance benefits and burdens, creating a society of solidarity and mutual assistance where both peace of mind and pain are shared. I do not mind if you disagree with my opinion. That is because what is decisively lacking in today’s politics is any real struggle of ideas about what kind of society we want to see.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 18 October 2023 under the title, “Saiko Seifuteinetto (II): Kisoteki sabisu no mushoka wo (Reconsidering Safety Nets: Making Universal Basic Services Free),” The Nikkei, 18 October 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Ide Eisaku

- Keio University

- safety net

- universal basic services

- low-income earners

- middle class

- benefits

- burdens

- consumption tax

- COVID-19

- anxiety

- income security

- dual-income households

- public finance

- public assistance

- medical assistance

- healthcare

- nursing care

- welfare

- housing

- education

- vulnerable

- stigma of relief

- “decent minimum”

- unemployment benefits

- housing benefits

- balance benefits and burdens

- social justice

- mutual assistance