Thinking About the Abe Cabinet in the Next Three Years

The ruling parties in the coalition, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and New Komeito, comprised the second largest force in the House of Councillors until the Upper House election this summer, in which they won more than half the seats. The parties consequently took a stable majority in both the Upper and Lower Houses, resolving a condition that had been dubbed a “twisted” Diet. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo probably could not have asked for a better election result.

YOSHIZAKI Tatsuhiko, Chief Economist, Sojitz Research Institute, Ltd.

Thinking generally about this, there will be no election in Japan in the next three years. Chances are that a stable period, which is rare in the kaleidoscopic world of Japanese politics, will arrive. What will the Abe administration aim for in this quiet period ahead? Many observers take the view that he might embark on revising the Japanese Constitution, a long-cherished dream Abe’s grandfather, former Prime Minister Kishi Shinsuke, passed down to him.

However, the degree of freedom allowed to Abe is not that high in light of the political agenda. In this article, I would like to consider priority issues for the Abe Cabinet in the next three years.

LDP with a Majority of Seats in Both Houses

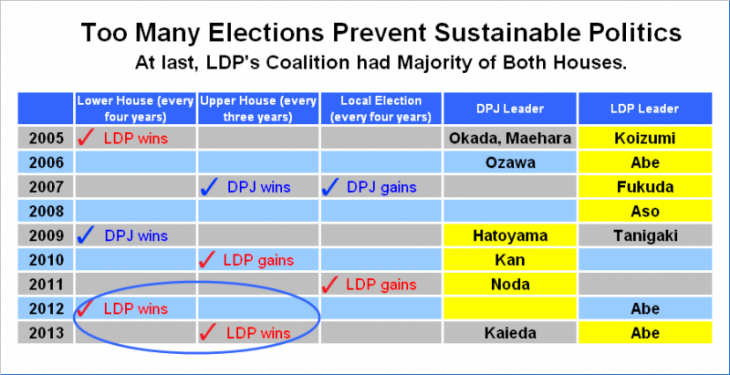

Critics have ridiculed the condition, with expressions like “revolving-door politics,” in which the Japanese prime minister has changed in almost every one of the last six years. Why has such a political situation emerged? It means that Japan’s political system itself has problems. There are simply too many elections in Japan.

In the first place, there are House of Representatives elections. The tenure of office for Lower House members is four years, but their actual tenure averages about three years because the House is dissolved. Then there are House of Councillors elections. The tenure of office for Upper House members is six years. The Upper House does not dissolve. Half of its seats are contested every three years. In addition to these, nationwide local elections take place every four years. Under these circumstances, Japanese politicians always need to be thinking about the next race. The revolving door for the prime minister came as the result of the two major parties continually fighting internally to find a new leader likely to secure victory in the next race. That is how things have been in the last six years.

The condition of the twisted Diet in which the two houses are at loggerheads had continued for a particularly long period after a crushing defeat the LDP suffered in the House of Councillors election in 2007. This Diet condition made it difficult for the ruling parties to run the government. The international financial crisis then struck Japan in 2008 and the Great East Japan Earthquake hit in 2011 while the ruling and opposition parties devoted all their time to politics, instead of policies, in this way. Such bad luck continued for Japanese politics for those six years.

The inauguration of the Abe administration as a result of the House of Representatives election at the end of 2012 and the LDP’s victory in the latest House of Councillors election mean this period of confusion has finally ended. Fortunately, the yen which had appreciated too much has been corrected under the positive effects of “Abenomics.” Share prices have been climbing too. The Japanese economy is beginning to enter a path of growth at a real GDP rate of about 3%. As a member of the country’s business community I am, frankly, rejoicing over the long-awaited end of the unproductive six years.

Is Japan Really Making a Shift to the Right?

The other day I had a chance to talk with an American scholar who was knowledgeable about Japan. I was a little surprised that this scholar was keeping a watch over the Abe administration with quite a bit of apprehension. It is fine for the administration to lift the Japanese economy up with Abenomics, but Japan’s nationalistic turn may set off China and South Korea and interfere with U.S. policies in Asia. The scholar was anxious about the direction in which Abe was heading.

People in the United States seem to think problems with how Japan perceives history disappeared under the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which ruled the country for three years and three months. Yet that is a long way from the truth.

Due to the nature of my job, I have many opportunities to give lectures at economic seminars held around the country. And on those occasions I speak with business managers in the regions. Many of them are absolutely furious about the three years and three months that the DPJ was in power. They are angry about the indecisive attitude the DPJ administrations adopted over territorial and historical perception issues, which allowed China and South Korea to apply pressure on Japan in an unrestricted manner. I have every reason to believe that such a sense of rage among conservatives became a driving force that gave Abe another chance to serve his country as prime minister.

However, more essential anger toward the DPJ lies in a place other than issues of territorial and historical perception. The DPJ once attacked the LDP over the national pension scheme and medical care issues. With those attacks, the DPJ requested that it be put in charge of these areas at least once, and said it could be replaced if it did a poor job.

Agreeing to that proposal, Japanese voters gave the DPJ a chance to actually take charge of their government. Once they came to power, the DPJ caused public finances to dramatically worsen by increasing annual expenditures such as by a child allowance without cutting other budget areas. They also put Japan’s security in danger by deteriorating Japan-U.S. relations. Dissatisfaction and anxiety had of course existed in the previous LDP era, but voters had never truly worried about public finance and security in those days. Compared with public finance and security, the national pension scheme, medical care and education, about which the DPJ was enthusiastic, were trivial issues for voters. Ultimately they came to think that giving political power to the DPJ was a mistake. They hated the DPJ’s incompetence, not its principles and position. The DPJ had let them down.

Thus the number of Upper and Lower House members affiliated with the DPJ dropped sharply, from more than 360 at its peak to a little over 100 through the last two elections. In the meantime, Diet members belonging to the LDP doubled, from 200 to 400. As a result of these developments, as many as 102 Diet members, including 73 LDP members, this year visited Yasukuni Shrine on August 15, the anniversary of the end of World War II. People overseas might interpret their behavior as a sign of Japan’s rightward shift, but we cannot ignore the aspect that their controversial visit to the shrine was only a byproduct of the strict voter appraisal of what the DPJ had achieved.

Prime Minister Abe seems to know the position he occupies well. To a certain extent he must meet the expectations of conservatives who have supported him. But he must also maintain a delicate balance. He has to do this because Japanese diplomacy may enter dangerous territory should its prime minister seriously take a confrontational stance against China or South Korea.

Abe’s stock phrase for China is: “The door for dialogue is always open.” This means he does not take the initiative and approach China himself, but he is ready to discuss matters whenever China knocks on his door. Diplomatic relations with Japan are in large part driven by domestic issues in China. Anti-Japanese demonstrations would not look good for the newly inaugurated Xi Jinping regime should they take place immediately after a Sino-Japanese summit. Given that, the only thing Japan can do is leave judgment to the other party and deepen friendships with other countries ahead of China and South Korea. In this connection, Abe seems to judge that relations with South Korea will naturally improve if relations with China should take a turn for the better.

Thus Abe has visited about twenty countries, most of them in Southeast Asia, in the eight months since his latest administration’s inauguration. For the record, the three prime ministers from the DPJ traveled to only seventeen countries in the three years and three months their party was in power. These figures clearly indicate how active Abe is in the field of diplomacy.

Abe’s Game Plan for the Next Three Years

We often hear the concern that the Abe administration might make a bid for constitutional revisions in the next three years and cause Japan to make a further shift toward the right. Each time someone voices this concern I reply that Prime Minister Abe must concentrate on economic issues at least for the next two years. He cannot afford to direct political resources to matters such as constitutional revision. I believe this script is obvious when we think, without harboring any strange illusions, about what he must do in the period ahead.

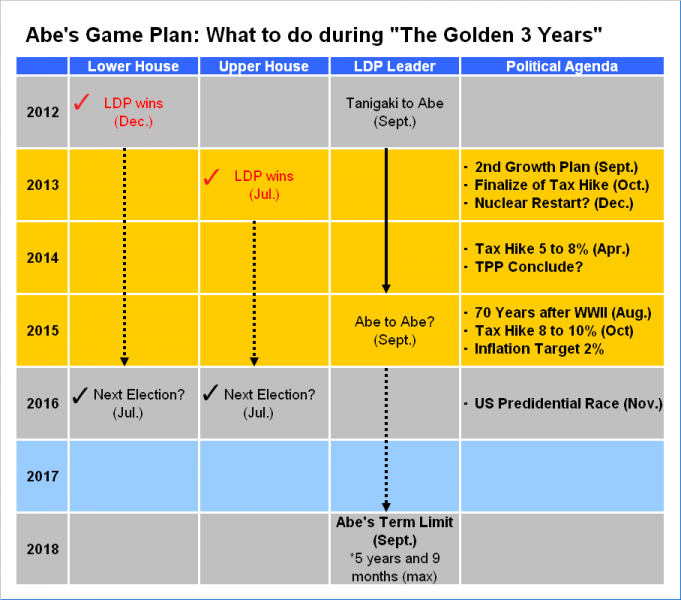

As I explained earlier, Abe does not need to worry about national elections for the next three years. The next House of Councillors election will be in July 2016. The House of Representatives election is expected to be held simultaneously with this Upper House election. A double election for the House of Councillors and House of Representatives has not been held for some time though it has happened many times in the past. I believe simultaneous elections will be a natural choice for Abe.

In that case, the period from the summer of 2013 to the summer of 2016 will be an almost miraculous period, one that could be called three golden years for Japanese politics. What will Abe aim to achieve in this period of stability? What will he position as political priorities for these three years?

The LDP has set two terms or six years as the maximum tenure for its president. The absolute must for Abe is to stay in the post through reelection in the LDP presidential contest in the summer of 2015. This is because approximately 400 LDP members, without exception, now in the Diet will go into an election in the summer of 2016. They will immediately start a campaign to oust Abe when they find their leader is unpopular. This same game was repeated over and over again in the last six years.

However, a long-term administration all the way through September 2018 comes into view if Abe wins this LDP presidential race and overcomes the double election in July 2016. His administration will be stretched to five years and nine months in that case. The duration will make Abe’s service as prime minister the third longest in the period since the end of World War II, replacing Koizumi Junichiro in third place.

The summer of 2015 will be a crucial period for Abe for that reason. But three obstacles stand in his way; all are economic issues.

(1) Consumption tax

There is a Japanese law that stipulates the consumption tax will be raised from its current level of 5% to 8% in April 2014. The Japanese government must implement the tax increase without inviting an economic downturn. The government must also aim at reducing budget deficits because it has made a public commitment to reducing them on a primary balance basis by 2015. The government must also study whether or not raising the consumption tax to 10% in October 2015 is possible.

(2) Commodity prices

Kuroda Haruhiko, governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), has set a 2% increase in consumer prices within two years as an inflationary target. This target is of course a public commitment made by the BOJ. The Japanese government is not responsible for its achievement. However, whether or not the target is within reach will become clear to everyone in the summer of 2015. In other words, the success or failure of Abenomics will be clear by that summer.

(3) TPP

Within the year 2013 has been called the target for concluding the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP Agreement). However, the actual conclusion of the TPP Agreement is likely to be delayed into next year. There is a strong possibility that the details of compromises for the agreement will be shaped into a bill and the bill will be in the stage of waiting for Diet ratification in the summer of 2015. Whether or not this could really happen is the third obstacle.

Handling the consumption tax is particularly important among the three obstacles. At the end of August 2013 under the title of “Intensive Examination Meetings,” Abe asked sixty experts for their opinions on the tax increase timetable. He is planning to make a final decision on the tax increase in early October. The tax hike is currently a subject of endless argument among economists.

There appears to be virtually no problem with the all-important Japanese economy through the end of March 2014. Personal consumption has been active. Capital investment in the private sector is likely to increase from this summer too. However, the situation may become entirely different at the start of the new fiscal year in April 2014. In other words, we can expect the Japanese economy to grow at a rate of about 3% a year in FY2013, but that prediction will become risky the moment FY2014 gets underway. This is because the burden on households will increase by a rough estimate of 15 trillion yen when summing up factors such as (1) a 3% increase in the consumption tax, (2) reactions to public works spending made in FY2013, and (3) last-minute demand growth before the tax hike anticipated at the end of March 2014 and a reactionary fall in demand from April of the same year.

Stated in another way, a downward pressure about 3% of GDP in size will emerge. Perhaps we can call this problem the Japanese “fiscal cliff.” All designs, including financial reconstruction plans and commodity price targets, will break down in the case the problem invites an economic downturn.

My opinion in this connection is to raise the consumption tax according to plan. For doing so, I think the government must take countercyclical measures at a considerable scale in the spring of 2014.

More Haste, Less Speed – It’s the Economy, Stupid!

Under the second Abe administration, politics have been working properly for the first time in a long while. The ruling parties have agreed to targets set by the prime minister without showing internal disorder. Bureaucratic machines have been performing their job of deciding matters without making a fuss. These are what I see as differences from the last six years. They are the reason why the approval rating for the Abe Cabinet has remained at a high level. The question is if Prime Minister Abe can sustain these conditions for two more years and generate tangible effects on his country’s economy.

Abe will have an extremely strong position in Japan if prospects arise for the three conditions of the consumption tax, commodity price targets and the TPP by the summer of 2015. After all, he will have the Japanese economy out of deflation, which has been a problem for many years, will have taken a step toward financial reconstruction and will have completed a large piece of homework called the TPP. In this case, Abe would have to be entering his third summer as the prime minister with accumulated political resources.

Political issues for conservatives will take on a touch of real possibility after Abe concentrates that much on the economic issues. To put it plainly, a crack may finally open on the issue of constitutional revision, which conservatives have had in mind for a long time since the end of World War II, when Abe in his third summer as prime minister starts saying, “I would like to seek the judgment of the people about constitutional revision in the double election scheduled next year.”

To the contrary, the view that the Abe administration will finally end with the election in the coming year will gain favor if Abe fails to fulfill the three conditions above. In that case, strong rivals will start appearing to announce their candidacy in the LDP presidential election scheduled in September 2015. The emergence of a strong opposition party is not necessary to overthrow the Abe administration.

To conclude, items on conservatives’ agenda, such as constitutional revision and historical perception, depend on how much Abe’s economic policies achieve in the next two years. With more haste and less speed Prime Minister Abe must first devote all his energies to economic issues.

Constitutional debates tend to shift in extreme directions by accident. I feel that both conservatives, who expect that Abe will surely carry out constitutional revision, and liberals, who think Abe is dangerous because he looks likely to revise the Japanese Constitution, belong to the same school of romanticism.

(August 31, 2013)