Concerns over Abenomics Regarding Projects to “Build National Resilience” Increasing Government Spending Again Will Do Little to Solve Anything

Japan’s regional areas are currently suffering from a declining economy, while the phenomenon of underpopulation is making matters even worse in those areas.

One possible solution that has been presented to solve this problem calls for increasing public works spending, supported by the idea of “Building National Resilience.”

This government strategy, however, which aims to revitalize regional communities through the help of large-scale infrastructure investment, appears to be going against the long-time social trend, and I am concerned that it will have the opposite effect and end up hampering the emerging community-driven initiatives to revive the economy and business in those regions.

KOMINE Takao, professor of Hosei University

Japan’s regional areas are plagued by a “population onus”

Currently, a population onus is taking place all across Japan. Let me briefly explain what a “population onus” is, as this concept doesn’t seem to be well known to the general public.

The term “population onus” was coined as the antonym to a “population bonus.” A so-called population bonus is when a demographic transition has a beneficial effect on the economy, and is typically used to characterize a period when there is a low dependent population ratio; i.e., the ratio of the population defined as dependent (the combined elderly and youth population) divided by the population of productive age. Conversely, a “population onus” (meaning a demographic burden) refers to a period when there is a high dependent population ratio.

Generally, the dependent population ratio tends to fall significantly when “baby boomers” reach working age after a certain period characterized by low birthrates. This period is characterized as a population bonus era, and Japan’s high economic growth period in the postwar years was a case in point.

But, as time goes on, baby boomers, who were once in the working-age group, will start to become senior citizens en masse, and the size of the productive population will shrink as a result of the low birthrates experienced in the preceding decades. This represents a “population onus” era, and Japan has been going through the population onus phase since around 1990. In a society characterized by a population onus, some phenomena are typically observed, such as a low labor force population, a low savings rate, and a faltering social security system. As seen from the above, we can conclude that a population onus presents a fundamental problem regarding our population issues.

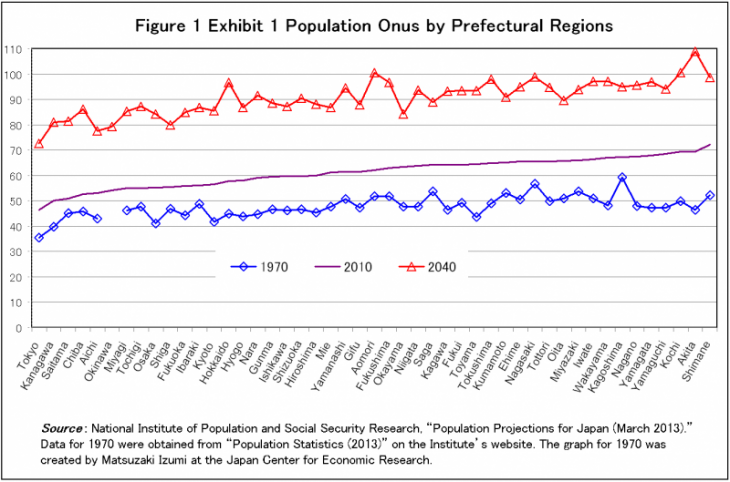

A population onus also poses a big problem for local communities, because an increase in the population onus shrinks the population of working-age people, which can cause the economies of local communities to decline. As proof of this, I would like to discuss the dependent population ratios of individual prefectures in Japan (see Exhibit 1). As seen in the graph, in the survey-selected years of 1970 (representing the past), 2010 (the present) and 2040 (the future), the extent of the population onus tends to be low in those urban areas that generally have high growth potential, such as Tokyo and Kanagawa, while regional prefectural areas such as Shimane and Akita with relatively low growth potential tend to be exposed to the risk of developing a population onus.

The difference in economic growth potential among prefectural areas leads to a shift in the productive population, which moves from regional cities with low growth potential to metropolitan cities with high growth potential. This, in turn, causes the population onus in regional cities to worsen. In sum, a vicious cycle is created due to the difference in economic growth potential among the prefectures, depending on the magnitude of the population onus, which encourages the labor force to move from low-potential to high-potential cities, which creates an even greater disparity in the degree of the population onus, and this widening gap, in turn, fuels even larger disparities in economic growth potential among prefectural areas.

To put an end to this vicious cycle, regional governments must create more stable jobs within their regions to prevent the productive population from flowing out of their regional communities and into metropolitan cities. I believe this is our most important challenge, and must be immediately addressed by regional governments and communities.

Evaluating a regional revitalization initiative driven by increased state public works spending

This raises a question: “How is the Abe administration dealing with this situation?” I must say that I am nervous about the country’s current rapidly expanding spending on public works as part of the three arrows of Abenomics, or Prime Minister Abe’s policy to revive the sluggish economy.

The “second arrow” of Abenomics is a massive fiscal stimulus, which I believe intends to increase public works spending in order to promote economic growth. This strategy is now steadily being implemented. In January 2013, right after the Abe administration was inaugurated, the government launched an emergency economic stimulus package consisting of 5.2 trillion yen in public works projects, with 15.6% more spending than the previous year in the approved FY2013 fiscal budget for infrastructure development. On top of this, a substantial new public works spending budget will very likely be included in the 5 trillion yen economic stimulus package to be launched in October, in an effort to cushion the impact of the forthcoming consumption tax hike.

In retrospect, the importance of Japan’s public works spending has a history of changing with the times while maintaining a close relationship with various socioeconomic issues in the respective regions. Based on my past professional experience as Director General at the National Land Agency, I am extremely concerned about the public works spending that is currently being expanded at a rapid rate. My concerns are based on the historical relationship that I have observed between state spending and regional areas, as explained below.

Historically, among industrialized nations, Japan’s fiscal spending on infrastructure projects has long been maintained at a relatively high level. This spending has gone up even further as a result of the series of economic stimulus packages featuring public works that have been launched since the 1990s in an effort to bail the country out of economic recession after the bursting of the bubble economy. For instance, the ratio of public investment (or public-sector fixed capital formation) to nominal GDP surged in the early 1990s, reaching 6.3% in 1993, two or three times the level of other industrialized nations at the time (3.5% for France, 2.1% for the United Kingdom, and 2.3% for the United States).

One characteristic of this surge in public investment is that it was utilized in an attempt to revitalize regional communities. Areas where per capita income is low have tended to show high per capita public investment.

In sum, the Japanese economy as a whole has tended to heavily rely on public works projects, and, among other things, regional economies’ dependency on public works is quite high, as public works spending has been used as a means of reallocating incomes among regional governments. The relatively large-scale public works projects being undertaken in regions with low per capita income or in areas with natural handicaps (described below) means that the scale of the corresponding public projects undertaken in urban cities is relatively small in

relation to their fiscal burdens. In other words, the government is reallocating incomes from metropolitan cities to rural regions through its fiscal spending.

When I was with the National Land Agency (currently part of the National Land and Transportation Ministry), in charge of revitalization projects for regions with natural handicaps, such as underpopulated areas, remote islands, mountain villages, and snowy areas, public investment was utilized as an effective means of reviving these areas. Each of these environmentally challenged areas was provided with additional fiscal assistance as prescribed by the respective laws focusing on regional development, where the central government provided a certain percentage of additional assistance to facilitate public investment projects while alleviating the socioeconomic burden for regional governments. In places such as remote islands and mountain villages, it is difficult to attract industries that have high employment capacity because of these environmental challenges. To deal with this situation, the government tried to artificially generate extra jobs in the fields of civil engineering and construction by undertaking infrastructure development projects in these regions.

As a result, regions with low growth potential have become highly dependent on state spending.

New initiatives are emerging to revive regional communities, while Abenomics is out of step with the times

A cutback in public works spending followed. Following the Koizumi cabinet, public investment was greatly reduced, with its ratio to nominal GDP falling to as low as 3.0% in 2008, down from its previously recorded peak level of 6.3%. Regional areas, which had grown used to getting help from the fiscal spending on infrastructure projects they had received over the years of generous state spending, were seriously affected by the cutback in fiscal spending.

Despite this, it seems that new initiatives are now emerging to redevelop regional communities—a social movement that represents a departure from the conventional way of regional development, which was driven by public works spending. This movement can be summarized as follows.

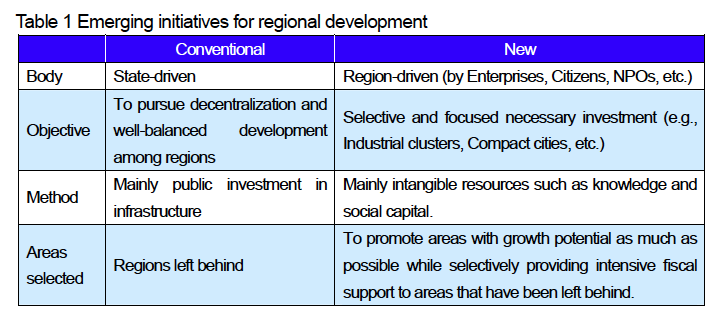

The first consideration is, “Who is going to take the initiative in a regional revitalization project?” In conventional efforts, the central government was the main player in implementing regional policies. The basic guidelines for strengthening the nation’s infrastructure are prescribed in the “Comprehensive National Development Plan” formulated by the government, and based on this, the nation’s infrastructure-related policies were gradually formulated. But this kind of state-driven regional development policy seems to have reached a critical limit due to fiscal constraints, and so on.

Recently, however, regional areas themselves have started to become major players in their redevelopment, with diverse bodies including regional governments, enterprises, colleges and universities, non-profit organizations (NPOs), and civil groups joining regional redevelopment initiatives.

The second consideration is, “What direction are we going in?” In conventional regional development efforts, the government has consistently taken the position of controlling “centralization” while promoting “decentralization.” This development concept has also failed to meet current needs, and has been replaced by a “centralization-oriented” attitude in recent years, as a shift toward the service industry along with the IT revolution has led to urban concentration, while local governments have begun pursuing compact cities amid a declining population. An “industrial cluster,” a platform consisting of the geographic concentration of interconnected businesses and research institutions, which exerts synergistic effects, is also related to this movement toward centralization.

Regional governments are also pursuing unique directions in development, capitalizing on their own community-specific resources rather than following across-the-board state-driven guidelines.

The third consideration is, “What kind of regions should be selected for development?” Essentially, there are two categories of regional development policies: (1) a policy to promote regions that deserve promotion efforts; and (2) a policy to save those regions that have been left behind. In conventional development efforts, government policy has tended to focus on answering the question, “How do we support those regions that have been left behind?”

As the government has been demanding that regions increase their respective average growth rates in recent years, regional governments are increasingly being asked to do their best to raise their local growth potential. Going forward, the central government will be required to “selectively support those regions that actually require state support.” In recent years, the government’s policy has shifted toward “promoting areas with growth potential as much as possible while selectively providing intensive fiscal support to those areas that have been left behind.”

The fourth consideration refers to development methods. In a conventional development program, as previously mentioned, tangible infrastructure investment has been a major component of fiscal spending. Again, this approach has also reached a critical limit, and in recent years it has been replaced by a software-oriented approach, such as “social capital-based” historical traditions and interpersonal confidence, as well as an industrial cluster comprising a geographic concentration of interconnected intellectual resources such as colleges and universities, research institutions, and a platform for business start-ups, all of which are believed to significantly contribute to regional growth.

Innovative approaches reflecting the paradigm shifts mentioned above have been gradually emerging (see Table 1).

However, the massive public works projects implemented as part of Abenomics’ economic policy seem to be rolling back the emerging new trends of regional initiatives to redevelop regional areas.

Prime Minister Abe’s aggressive fiscal spending on infrastructure projects is supposed to boost the economy and increase national resilience. With the rapid expansion of public works spending, the ratio of state spending to nominal GDP is quite likely to rise again, with the civil engineering and construction companies that were expected to go away coming back. A regional development approach that is less dependent on infrastructure projects is likely to revert to its previous form. What we learned from our experience in the 1990s is that economic growth or regional development driven by public works spending isn’t sustainable, and will leave us with an adverse legacy called a “budget deficit.”

Public works will, indeed, create demand, helping to raise the economic growth rate as long as the works projects are being executed. But this approach is finite, with a limited fiscal budget. When the projects end, growth in the public works-dependent regions will stop at the same time.

I am concerned that the regional economic growth that will be provided by these public works might be a departure from the direction that many of these regions are moving in, and therefore, the growth is likely to be unsustainable.

From an industrial perspective, it seems that many regional areas are striving to revitalize their economies and generate employment opportunities by promoting local businesses that capitalize on indigenous traditions, agriculture, forestry and fisheries linked to local communities, and service industries such as tourism. Very few regions plan to expand the civil engineering/construction business created by public works to become local leading industries.

Regarding jobs creation, many of these civil engineering and construction workers come from outside the relevant region on temporary assignment, which doesn’t necessarily directly help to provide stable opportunities for the local labor market.

The idea of building national resilience also involves some hidden political factors that may promote a return to the old-fashioned state-controlled public works in regional areas. “A Draft Proposal for Building National Resilience,” as originally drawn up by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), features three pillars, which can be summarized as follows:

1. To realize the formation of multiaxial national land, while decentralizing Tokyo’s capital functions and eliminating vulnerabilities in national land.

2. To achieve well-balanced development among different regions (create multiaxial national land) by promoting regional development that capitalizes on a region’s characteristics, while expanding the size of the residential population in the regions.

3. To implement large-scale disaster measures while ensuring the sustainability of political and socioeconomic systems in case a disaster actually occurs.

The above draft proposal stipulates that the government will create a “National Land Resilience Basic Plan,” based on which broad regional areas, including regional municipalities such as prefectures, cities, towns and villages, will be responsible for developing “resilience” policies.

The draft initially proposed by the LDP is not necessarily going to be finalized as the National Resilience Bill, but the points I have described above do reflect the initial ideas in the draft. There is no doubt about that. Having reviewed the contents of the draft bill proposed by the LDP, I am under the impression that such a framework would lead to more “state control (meaning the regional government will be subject to the central government’s basic nationwide scheme),” further “decentralization,” more “hardware-oriented public investments,” and more “focused spending, mainly on the regions being left behind (under the banner of pursuing “well-balanced development among different regions”).

The above observations have raised concerns that Prime Minister Abe’s economic policy of aggressive fiscal spending on infrastructure projects will not lead to sustainable regional growth. Further, his economic policy may even run the risk of discouraging the new redevelopment initiatives that are emerging in the respective regions and promote a return to the old conventional framework.

Translated from “Tokushu – Kaishisuru Chihotoshi / Abenomikusu “Kokudo Kyojin-ka” eno Kenen: Kokyo-toshi Kaiki dewa Nanimo Kaiketsushinai (Feature – The Decline of Regional Cities / Concerns over Abenomics Regarding Projects to “Build National Resilience”: Increasing Government Spending Again Will Do Little to Solve Anything),” Chuokoron, December 2013, pp. 40–45. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [December 2013]