Interpreting the Upper House Elections: Please don’t squander your political capital, Prime Minister! ―Putting growth strategies and fiscal health ahead of constitutional reform

< Key Points >

- Important to push ahead with the TPP, deregulation and infrastructure development

- Need to think rationally about whether constitutional reform is really a top priority

- DP needs to set out economic policies to put pressure on LPD

Takenaka Harukata, Professor, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies

Both the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Komeito emerged victorious from the Upper House elections. In addition to the decision to delay an increase in consumption tax, voters sided with the Abe administration’s diplomatic and security policies, including related legislation, as well as the government’s economic and social policies.

In this article, I would like to take a look at future political issues from the point of view of domestic affairs. By way of a conclusion, I would like to see Prime Minister Abe Shinzo prioritize growth strategies, including deregulation, and fiscal health ahead of constitutional reform.

The LDP has restored a single-party majority in both houses for the first time in twenty-seven years. Prime Minister Abe has now won four national elections in succession, thereby establishing an even stronger power base for his administration. Komeito appears to have lost some of its say within the administration. Nonetheless, the LDP and Komeito have formed a close relationship through the election. As the LDP will also need to work with Komeito to push through constitutional reform, Komeito is likely to retain a certain degree of influence.

Including the likes of Initiatives from Osaka (IfO) and the Party for Japanese Kokoro (PFG), as well as the pro-reform LDP and Komeito, more than two thirds of the seats in the Upper House are now occupied by “pro-constitutional reform forces.” The ruling party also holds more than two thirds of the seats in the Lower House, meaning that the stage is set for the government to initiate constitutional reform.

With that in mind, one of the issues that the Prime Minister should be addressing is that of policies to promote economic growth, as stressed by the Prime Minister himself during the election. One thing that the government can do to breathe life into the economy is to create an environment that will make it easier for companies and entrepreneurs to go about their activities. It is important to focus on areas such as trade liberalization, deregulation and infrastructure development.

The immediate priority in terms of trade liberalization first of all is to enact legislation relating to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement. Although open to influence by the US presidential elections, it is essential that Japan demonstrates that it is fully committed to liberalizing trade. Japan should also be pushing ahead with trade liberalization negotiations on other fronts, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in East Asia.

The second key point is deregulation. When the current administration came to power, Prime Minister Abe said that he would make Japan “the most friendly country in the world to do business,” and that he would make himself as a “drill” breaking bedrock regulations. Unfortunately, the pace has slowed somewhat, particularly over the last year.

Of the various deregulation measures that have been discussed to date, the bill to introduce non-time-based wage systems (“white collar exemption”), based on results rather than time, are yet to be introduced. Similarly, agricultural land owned by companies remains tightly regulated. In the World Bank’s business environment rankings, Japan has slipped from 20th in 2012 to 34th in 2016.

One fact that needs to be taken into consideration when exploring deregulation is that, although advances in information and communications technology have paved the way for new businesses, the existing regulations often work as barriers that impede the launching of new businesses.

For example, the provision of passenger services using a private vehicle, as typified by Uber Technologies in the United States, is currently against the Road Transportation Act in Japan. Rather than allowing exceptions in certain areas, the ban should be lifted everywhere, including Tokyo. There are also plans to lift the ban on people providing accommodation services in privately owned houses and apartments such as the AirBnB under certain conditions. Accommodations in “owner-occupied” homes should be fully liberalized at least.

The third key point is infrastructure development. In view of increasingly fierce international competition to attract companies with neighboring Asian countries, particularly important measures include increasing arrival and departure slots at Haneda Airport, setting up smaller airports for international flights, and improving airport access from major cities.

Prime Minister Abe has already set out guidelines on formulating economic measures. These revolve around improving infrastructure, including upgrading port facilities and building bullet train lines, and reducing the pension eligibility age. I had hoped that the Prime Minister might capitalize on his election victory to tackle deregulation in more politically difficult areas.

Another priority that the Prime Minister should be focusing on is fiscal restructuring. Japan is in the worst fiscal situation among the G7 countries, with over 35% of its budget dependent on borrowing. It is highly likely that such a fiscal condition has made younger generations feel anxious about the future and slow down consumer spending. Despite such a serious fiscal condition, the Prime Minister has postponed plans to increase consumption tax to 10% until October 2019.

The more serious issue however is the strong possibility that Japan will be unable to achieve its target of improving fiscal condition even after another hike in the consumption tax rate.

Abe’s government is sticking to a target of bringing Japan’s primary balance, at both the national and local levels, back into the black by fiscal 2020. Perhaps the Prime Minister is thinking that this can be achieved by increasing taxes in October 2019. According to cabinet estimates however, the country’s primary balance will still be 6.5 trillion yen in deficit by fiscal 2020, even allowing for the increase in consumption tax and a real growth rate of at least 2% from fiscal 2018 onwards.

The only options are therefore to reduce spending or take steps to increase revenue. Although Abe’s government has adopted a policy of limiting increases in spending on social security to around 500 billion yen annually, it will need to come up with additional measures on top of that. Examples that would be worth considering include reducing medical expenditure based on analysis of differences in spending between regions, or raising the pension age.

One potential option over the medium to long term would be to increase consumption tax over 10%. Taking into account the regressive nature of consumption tax however, and fairness in terms of tax burden, the government would be better to start by increasing tax on income from financial asset or introducing a consolidated taxation system, if they want to get the public on board. High income earners, who tend to earn a higher percentage of their overall income from financial transactions, are currently taxed separately on income from financial asset, which is taxed at a lower rate than salaried income in many cases.

Prime Minister Abe has set out his position on initiating discussions regarding constitutional reform via the Commission on the Constitution, commenting, “although based on our party’s proposal, it will take political skill to establish a two thirds majority.”

There is no denying that it is worth discussing constitutional reform. The issue is the order of priority given to individual policies. It takes a great deal of political capital to bring about constitutional reform. The trade-off is that other policies inevitably get delayed. This is something we have already experienced previously.

In the general election in December 2014, the Prime Minister set out his plans for the country’s economic policy in the form of “Abenomics.” After the election however, Abe focused on enacting security-related legislation. As a result, certain other policies took longer to materialize. Revisions to the Labor Standards Act to introduce the aforementioned white collar exemption policy, were not enacted. The fact that Abe’s government chose not to call an extraordinary Diet session meant that policy implementation was delayed further still. The proposed revisions to the Labor Standards Act still remains tabled.

From the point of view of the international situation, security-related legislation was a necessity. If you stop to think about current economic and social conditions however, is constitutional reform really a top priority?

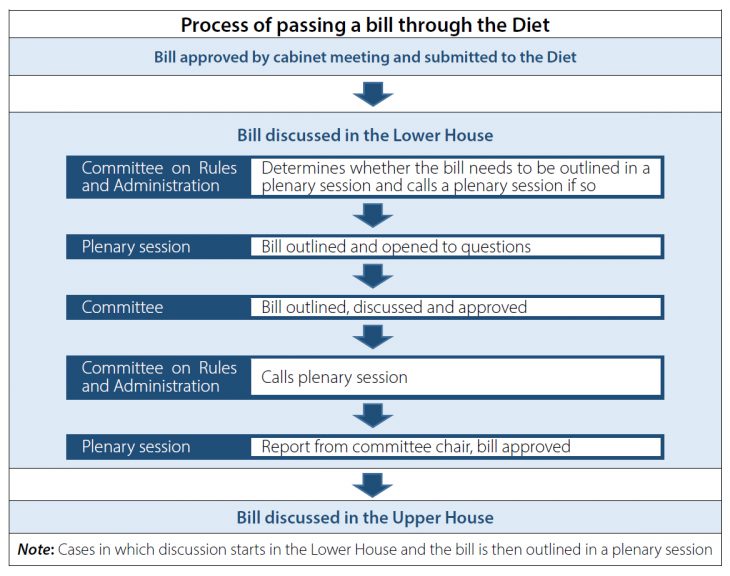

The Prime Minister may have honed his leadership skills, but he is still limited to some extent. The reason for this is down to the way the Diet operates. Bills have to go through the Diet based on the procedure outlined in the diagram before they can be enacted. Each committee has a great deal of authority, with important bills channeled through a select number of committees such as the Committee on Health, Labor and Welfare. This structure means that certain lawmakers from the ruling party have a great deal of influence over the success of individual bills. Even a prime minister might cannot ignore the wills of the important legislators in formulating policies.

This is the main reason why it will take a tremendous amount of time and energy to make headway with deregulation. It will require a considerable amount of political capital to implement growth strategies and improve fiscal condition. I would urge the Prime Minister to think rationally about his priorities and prioritize these two issues above all else.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the role of the Democratic Party (DP). Despite forming a united front with other opposition parties and achieving some success in individual seats, the DP ended up with fewer seats overall. This was an inevitable outcome. From Abenomics and constitutional reform to the TPP, the DP did nothing but oppose. This relentless negativity made it hard to appeal to voters.

The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the DP’s predecessor, challenged the LDP administrations by making pledges to structural reform and tackling social disparity. If the party intends to stand up to the LDP, including blocking constitutional reform, the DP needs to put forward economic policies and engage in political debate, so that the LDP starts to feel under pressure. That will no doubt be the key to restoring the party to full strength over the long term.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 18 July 2016 under the title, “Saninsen wo do yomitokuka (2): “’Shusho, Seijishihon Katsuyo Ayamaruna ― Kaiken yori Seicho-senryaku Zaisei ni” (Interpreting the Upper House Elections (Part 2 of 3): Please don’t squander your political capital, Prime Minister! ―Putting growth strategies and fiscal health ahead of constitutional reform)” The Nikkei, 18 July 2016, p. 16. (Courtesy of the author)