Decoding public opinion polls to understand the Japanese people’s fickle attitudes towards the constitution: A look back at the constitutional revision debate and the “Neo 1955 system”

Ideological confrontation repeats itself

Prof. Sakaiya Shiro

For postwar Japan, the constitution issue always exists as a point of dispute (either apparent, or latent), and has characterized the form of politics. The composition of the constitutional revision debate among elites, as well as the nature of attitudes towards constitutional revision among voters that provide the background to debate, appear to typify the particular nature of the political arena at any one period. Viewing the issue from this perspective, we can now describe Japan’s politics as a “Neo 1955 System” (see column below). This doesn’t simply refer to the situation of one strong party and many weak ones that we have seen in recent national elections. A more important point is that the issue of revising article nine of the Japanese constitution has once again arisen to be a key point of debate and as the determining factor in the battle between political parties.

The turmoil caused by the splitting up of the Democratic Party in 2017 was a symbolic event. Just before the Lower House elections of that year, a large number of Democratic Party representatives tried to merge with the Party of Hope. However, the problem was their attitudes towards article nine and national security policies. The Party of Hope side made it a condition of joining the party that there be agreement on fundamental issues related to the security guarantee and attitudes towards the constitution. Because of this, left wing representatives from the Democratic Party were excluded and set up the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan by themselves. The divided opposition parties were forced into a tough battle during the election for the Lower House and this allowed the LDP to steal victory while they fought among themselves.

Today, now that the election is over, the LDP (the massive ruling party) and Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (the largest opposition party) are facing up against each other in the Diet over the constitutional issue. The current political set up, in which a right-wing party actively calls for constitutional revision and a left-wing party opposes those calls, reminds us of scenes from the 1955 System, specifically the ideological confrontation between the LDP and the Japan Socialist Party.

[Column]

The Neo 1955 System — an old yet new right-left split

The difference between the stances of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Constitutional Democratic Party on the issue of article nine revision is very clear. According to a survey of each party’s members by the Asahi shimbun, 74% of Liberal Democratic Party members were in favor of clarifying the role of the Self-Defence Forces via the constitution, while 7% were against. The respective figures for the Constitutional Democratic Party were 2% in favor and 94% against.

This situation, in which the ideological point of dispute that is revision of article nine so clearly divides the stances of the main parties, and in which the issue has effectively become the focus of contention, is similar to the structure of contention between the political parties in the 1950s. The 2017 break-up of the Democratic Party is also reminiscent of the 1950s break-up of the Socialist party over security policy (when its right-wing split off).

Divisions over the security treaty and article nine extend as far as the awareness and actions of ordinary voters. Today’s voters are (correctly) aware that the constitution and security issues are key points of contention for politicians, and they make their political decisions with that in mind.

For example, during the 2017 lower house election, a Yomiuri shimbun poll on support for and opposition to revision of article nine found that 60% of those planning to vote for the Liberal Democratic Party were in favor and 18% against, while of those planning to vote for the Constitutional Democratic Party 10% were in favor and 79% against.

This situation, in which there is such a clear division over the constitution issue between the position of those supporting the Liberal Democratic Party and those supporting the largest opposition party, is also very reminiscent of the 1950s (in fact, the split is even more clear than in the 1950s). According to a November 1955 Asahi shimbun poll, 44% of Liberal Democratic Party supporters were in favor of constitutional revision, while 19% were against. Meanwhile, 26% of Socialist Party supporters were in favor and 48% against.

In fact, Japanese politics from the 1960s to the beginning of the 2000s departed from the pattern mentioned above, while the article nine issue became less important as a point of contention, both among politicians and among voters (please see The Constitution and Public Opinion for more information).

In short, the rise in prominence of the article nine revision issue to this extent is a phenomenon both old and new. This is the reason why I call today’s political situation a “Neo 1955 System.” Roughly sixty years on (the traditional age of retirement in Japan), Japanese politics has returned to its point of origin.

The way in which the stances of opposition parties towards national security policies obstructs their coming together, thus helping the LDP achieve one party rule, is also no different to the 1955 system.

Since the 1990s, there have been various structural reforms aimed at reforming the political economic system (and all ambitious ones at that). Nevertheless, the nature of contention between the political parties today is similar to that sixty years ago. This speaks to the fact that, for the elite, the constitutional issue has continued to be an important and deep point of contention throughout the postwar period.

But why is the constitutional issue so far from solution? Why has constitutional revision not occurred even once, or why doesn’t the issue slowly fade away? Even though the Japanese constitution is classified as a “rigid constitution,” compared to other advanced nations (those that have experience of constitutional revision) there are no unusually high hurdles to revision inherent to the system itself.[1] If this is true, we should think about causes in society that can explain why the issue has remained unsolved. In other words, it is necessary to seek the reason in the attitudes of voters towards the constitution.

The illusion of a strong consciousness of the constitution among the people

However, I do not wish to make some hackneyed statement such as, “it is only the strong will of ordinary people that has preserved the constitution against repeated reactionary plots by advocates of constitutional reform among the elite.” In fact, personally I believe that this interpretation of postwar history has absolutely no validity. That’s because the “truth” that the people have had a strong attachment to the constitution throughout the postwar period in the first place is false.

Although opinion polls are used to measure attitudes among the people, caution is necessary when interpreting those results. When people are asked about the rights and wrongs of article nine revision, the general direction of replies will vary depending not just on how the questions and options are expressed, but also differences in the survey method such as face-to-face or telephone polls. If we don’t pay attention to these methodological characteristics in various polls and just make ad hoc references to poll results as we find them, there is a chance our understanding of public opinion will be distorted.

For example, one poll that has been frequently quoted to date is a May 1946 poll by the Mainichi shimbun that asked, “Is an article to renunciate war necessary?” In answer to this, an overwhelming majority of 70% replied “necessary” while 28% replied “not necessary.” Many commentators have since argued that an overwhelming majority of the people have supported article nine since the enactment of the constitution; and the basis for this argument is chiefly this data.

But the issue here is the distinct method used to conduct this survey; namely, the survey was limited to the “well-informed classes” (the expression used by the Mainichi shimbun). Some 40% of the subjects polled in the survey were university graduates, while women and farmers only accounted for around 10%, so the survey completely failed to reflect the actual make-up of the population at the time.

Once this is pointed out, it becomes clear that it is hard to ascertain the attitude of the average voter at the time from this poll. Yet, during discussion to date almost no attention has been paid to the nature of the poll’s subjects, while this “70% necessary” figure has repeatedly been used as the basis of weakly founded statements concerning the attitude of the whole electorate.[2]

In order to accurately ascertain public opinion during each period, a painstaking comparative investigation of the many and varied past polls is essential, and not just in terms of their results but also their methodology. This is precisely the work I attempted in my book The Constitution and Public Opinion (Chikumasensho). In order to systematically clarify Japanese attitudes towards the constitution, when writing my book I attempted to collect results from all the surveys of attitudes towards the constitution conducted by major organizations in the postwar period. Using these results from the more than 1,200 surveys that were the subject of my investigation, I will now consider the attitude of Japanese people towards the constitution in the postwar period.

Firstly, let us investigate the type of questions that I call “general revision questions.” General revision questions such as, “Do you think it is necessary to revise the constitution?” are those that ask generally about the right or wrong of constitutional revision without specifying an article or articles. There is no great change to how questions of this sort are asked during different periods, and because the survey organizations vary little in form it is easy to compare the results.

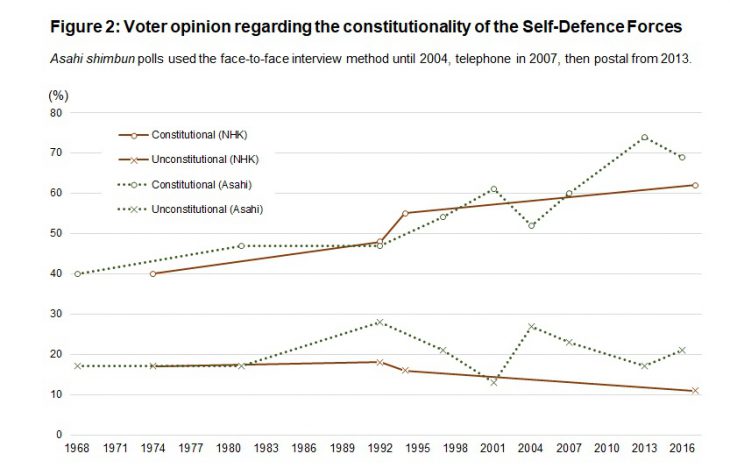

Figure 1 shows the results of general revision questions from postwar polls in chronological order. Each bar on the graph shows the result from one survey. The graph’s vertical axis shows the ratio in favor of revision minus the ratio in favor of protecting the constitution (percentage points). When the figure is close to zero the survey results were a close tie between those in favor and against. The further the bar extends upwards the more respondees to that survey were in favor of revising the constitution.

From this graph, we can establish the fact that there was almost no time during the whole of the postwar period when the argument for protecting the constitution clearly dominated among voters. The only notable time when arguments for protecting the constitution dominated was the 1980s, while during other periods those in favor of revising the constitution were clearly in the majority, or the yes and no sides were at least neck and neck.

We certainly cannot use this data to make statements such as that postwar Japanese have viewed the present constitution as something sacred and a kind of inviolable principle. It is clear that during the 1950s, and the beginning of that decade in particular, the argument for revising the constitution dominated. Even during the high growth period of the 60s and 70s when there is a tendency to assume that the argument for protecting the constitution spread widely in society, there were in fact about as many supporters for revising the constitution as for protecting the constitution.

Incidentally, in the poll which appears to be the origin of general revision questions, a January 1952 survey by the Yomiuri shimbun, there was a large gap between those in favor of constitutional revision (47%) and those against (17%). Regarding this result the Yomiuri made a harsh comment (February 8, 1952): “The people have no particular attachment to the current constitution.”

Yet, because general revision questions do not directly ask which article or articles should be revised (or how) there is a large amount of room for interpretation. Some people may well raise the objection that, if we were to analyze polls with questions that clearly narrowed their focus down to revision of article nine, the results might give an impression different to that in figure 1.

Since there is broad variation in the way that questions regarding revision of article nine are asked, and because that variation creates different tendencies in the answers, comparing such surveys is not easy. In conclusion, however, even if we look at just article nine, it is hard to say that the consensus of opinion in postwar Japan has been one of continuous ardent support.

It is well known, I think, that from the 1990s there were many voters amenable to the idea of article nine revision, but I would like to look at two symbolic sets of survey results that came before that. One is a March 1952 poll by the Mainichi shimbun that is an early example of a question about support and opposition to revision of article nine. This poll asked about support and opposition regarding “constitutional revision in order to have armed forces” and the results showed that support (43%) greatly exceeded opposition (27%). (These results should be compared to the May 1946 Mainichi shimbun poll mentioned earlier). The other is a December 1980 poll by the Asahi shimbun that serves as an example from the 1955 System period. In answer to the question “Should the constitution be changed to clearly recognize the Self Defence Forces,” 44% said they were in favor (and 41% against).

I cannot discuss this in any more detail here, but I recommend consulting my book The Constitution and Public Opinion for a comprehensive investigation, including issues other than article nine. In any case, the simple explanation above should make it clear that the preference for supporting preservation of the constitution among postwar Japanese was, at the very least, not as strong as many intellectuals originally thought.

Japanese people do not have strongly held views on the constitution

Given that voices in society that favor constitutional revision have not been small in number however, why have they not been able to realize that even once so far? The reason is that, even though there were few voters actively opposed to the various arguments for constitutional revision, arguments actively in support of revision did not become widespread either. In figure 1, we can see how at the beginning of the 2000s (the time of the Koizumi administration) there was what we could call an overwhelming number of voters who supported constitutional revision in general. This, however, is due to the influence of the constitutional revision debate focus at that time broadening from article nine to other issues, such as a system for the prime minister to be elected by public vote. Specific issues (in particular the arguments for revising article nine) were not as keenly discussed as this graph would imply.

The average Japanese person does not have strong opinions on either maintaining the current constitution, or revising it. To put that another way, Japanese people during the postwar period have not actually been concerned with the constitution. That is why the elite group that favors constitutional revision has not succeeded in actively mobilizing public opinion to their cause. From the perspective of politicians, the constitutional issue is not an advantage for their election strategy (albeit not a minus either), and is not a point of contention that delivers votes.[3] The “de-ideologicalization” of Liberal Democratic Party politicians during the high growth period, as well as the progression to competitive “vote-bringing” pork-barrel politics, needs to be understood in this context.

Even before we discuss whether Japanese people have a clear stance on the contentious (difficult) issue of constitutional revision, we must acknowledge that most Japanese people have no interest in the text of the constitution in the first place and do not fully grasp its contents. We can see this in various polls, both old and new. According to a February 1952 Asahi shimbun poll, 67% of respondees had not read the constitution, even sections. In a government poll almost two decades later in February 1971, 60% of respondees had still “not read the constitution.” Considering that during this gap there was a dramatic increase in the number of voters who had been made to read the new constitution as part of their school education, we have to surmise that only a very few people decided to read the constitution of their own accord in other circumstances.

Even before we discuss whether Japanese people have a clear stance on the contentious (difficult) issue of constitutional revision, we must acknowledge that most Japanese people have no interest in the text of the constitution in the first place and do not fully grasp its contents. We can see this in various polls, both old and new. According to a February 1952 Asahi shimbun poll, 67% of respondees had not read the constitution, even sections. In a government poll almost two decades later in February 1971, 60% of respondees had still “not read the constitution.” Considering that during this gap there was a dramatic increase in the number of voters who had been made to read the new constitution as part of their school education, we have to surmise that only a very few people decided to read the constitution of their own accord in other circumstances.

Of course, voters who have hardly read the constitution do not have a sufficient grasp of its contents. In fact, according to a 2005 academic poll[4], in answer to the multiple-choice question “what number article do you think includes the article of war renunciation?” 29% of respondents did not know. Some 67% got the answer right, but bearing in mind that it was a multiple-choice question with four answers, perhaps 50% got the answer right without guessing. There is no doubt that had this been a free-answer question rather than multiple choice, the number of people who answered “article nine” would have been much fewer. In short, it is not necessarily true to begin with that the existence of article nine within the constitution is “common knowledge” among the people. That these ordinary voters have any strong interest in the constitution (still less affection for the current constitution) could only be called a very optimistic interpretation.

As one more phenomenon that symbolizes the attitude of Japanese people to the constitution, I would like to point out the lack of opposition to unconstitutional legislation among many voters. For example, an October 1973 Yomiuri shimbun poll asked the question: “If the supreme court determined that the Self-Defence Forces were unconstitutional, what should be done about the Self-Defence Forces?” In answer to this, a total 30% of respondees sought a solution to the unconstitutional situation, with 10% saying “they should be dissolved,” and 20% saying “the constitution should be revised to make the armed forces legitimate.” On the other hand, more than 40% of respondees replied with answers that implied that article nine and the Self-Defence Forces should continue to coexist in some form. Some 13% said they “should be reduced in size,” while 32% said that “the will of the people regarding the status of the Self-Defence Forces should be consulted via a general election.”

In recent years, a debate has developed vis-a-vis accepting the exercise of the right of collective defense. On this point, Yomiuri shimbun polls explained matters to the effect that administrations had to date interpreted the right of collective defense as unconstitutional, then asked whether this prohibition should be lifted or not. According to the results of these polls, in any one year the group that “accepted exercise of the right through constitutional revision by interpretation” was the same size or larger than that which “accepted exercise of the right through explicit change to the wording of the constitution.” For example, in a February 2014 survey, 22% said that “the constitution should be revised to exercise the right of collective defense” while 27% said “the interpretation of the constitution should be changed to exercise the right of collective defense.” These results should be seen as evidencing a lack of attachment to any particular reading of article nine, rather than any affection for the wording of the current article nine.

In this vein, let us now look surveys on the Japanese military legislation enacted in September 2015. There is a widespread awareness among Japanese voters of the unconstitutionality of this legislation. For example, an Asahi shimbun poll that took place right after the legislation was enacted (in September) found that 51% of respondees viewed it as unconstitutional and 22% constitutional. The results of a Mainichi shimbun poll that took place the same month were similar, with an overwhelming majority believing it was unconstitutional (60% vs 24%). Additionally, we can assume that even many of the voters who decided it was constitutional must have heard that numerous legal experts considered it unconstitutional. Yet, in all the polls that asked whether this “unconstitutional legislation” should be repealed, those who sought to do so remained in a minority. In a February 2016 Kyodo News poll, those in favor of repeal were 38% and those against 47%. A poll by the Nihon keizai shimbun the following month showed a similar result (35% vs. 43%).

This data suggests that there are not a few voters who do not seek abolition of the right to collective self-defense, even in situations where they are well aware of inconsistency between the wording of the constitution and current policy.

The tendency of voters to confirm the current situation

But in reality, when it comes to article nine, most ordinary voters are not aware of the issue (i.e. the one that has concerned politicians and intellectuals) that there is inconsistency between the wording of the constitution and actual policy. To put that another way, the portion of the population that considers the security policies actually being put into practice as unconstitutional is not large.

To date, the Japanese government has on a number of occasions made important shifts in its security policies in reaction to changes in the international environment. Most of these changes in policy, at least on the surface of things, have tended to move policy further away from the wording of article nine; even taking into consideration that there are various academic interpretations as to how much may be permitted by the current article nine. Yet, on each occasion voters have in time shifted their understanding of article nine and come to view these new security policies as according with the constitution.

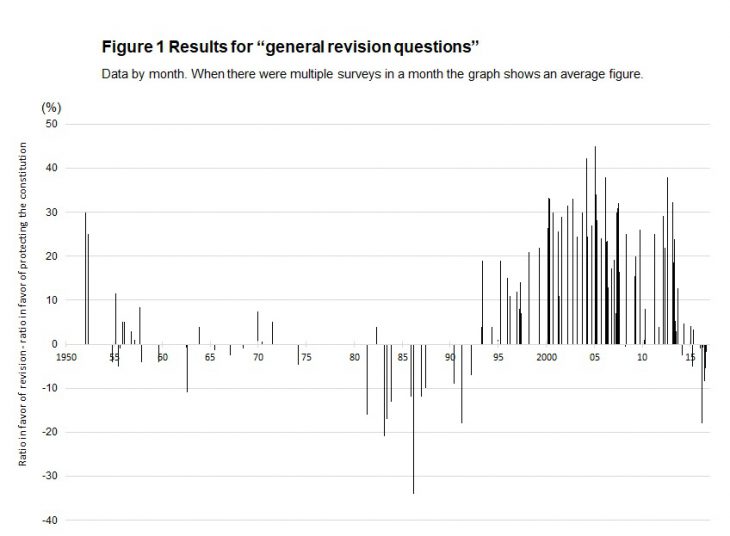

This point is very apparent from attitudes towards the Self-Defence Forces following the shift in GHQ and government policy at the time of their establishment in 1954. Figure 2 chronologically plots the results of NHK and Asahi shimbun polls regarding voter attitudes to the constitutionality of the Self-Defence Forces.

It is necessary to exercise some caution over the results since both polling organizations changed their polling methodology mid-way through the period. Yet, even taking that into consideration, from figure 2 we can conclude that arguments for the constitutionality of the Self-Defence Forces have become more widespread as time has gone on. In the 1968 and 1974 polls, 40% of respondees thought that the Self-Defence Forces were constitutional, but by the second half of the 1990s that figure was over 50%, irrespective of the survey organization or method. Recently, 60% to 70% of respondees are in the “constitutional” group.

In surveys by other organizations too (at least up to the 1970s) there is evidence to suggest the view that the Self-Defence Forces are constitutional was not as prevalent as it is now. A September 1972 Mainichi shimbun poll showed a small gap between unconstitutional (39%) and constitutional (45%). An October 1973 poll by the Yomiuri shimbun asked about the constitutionality of the Self-Defence Forces following a district court judgment (the Numazu case) in the preceding month. The results of that poll showed that more people supported the ruling of unconstitutionality (34%) than opposed it (32%).

As coexistence between the Self-Defence Forces and article nine effectively continues, over time the argument for the constitutionality of the Self-Defence Forces has gradually permeated society. In recent polls we might even say that the shift in opinion has headed in one direction alone. A March 2017 NHK poll found a large gap between those who thought the Self-Defence Forces were unconstitutional (11%) and those who thought they were constitutional (62%). With acceptance of the status quo having come this far, it is not likely that Prime Minister Abe’s suggestion of adding an additional Self-Defence Forces article will receive enthusiastic support.

We can see the same tendency with the issue of overseas dispatch of the Self-Defence Forces, a topic of political contention in the early 1990s. At the time of the Gulf War, the Self-Defence Forces expanded their sphere of operations overseas with peacekeeping operations and other activities. This wasn’t a situation that governments up to the 1980s had imagined and it was a historical and significant turning point for postwar security policy.

Until the second half of the 1980s, the majority opinion of voters was that “it is undesirable for [the Self-Defence Forces] ever to go abroad” (Yomiuri shimbun, July 11, 1988). Yet, when the Self-Defence Forces actually began to be dispatched abroad, public opinion turned 180 degrees. According to the results of polls by the Yomiuri shimbun and the Asahi shimbun, from 1990 to 1993 acceptance of overseas dispatch increased until it was head-to-head with opposition to dispatch (and possibly more). What’s more, as a result of repeated international cooperation activities over time, in recent years 50% of respondees to a February 2012 Yomiuri shimbun poll even said it was “OK to allow” Self-Defence Forces that are participating in peacekeeping operations overseas to use weapons to help foreign forces when they are under attack in a separate location,” which was more than the 39% who said it was “better not to allow” this. And this was despite it being made clear to respondees that the government interpreted use of weapons as unconstitutional.

As a recent example, we can observe a similar shift in public opinion (i.e. an affirmation of changed policy or a trend towards a broader interpretation of the constitution) after the start of the second Abe administration and around the time security policy regarding the right to collective defence shifted direction. According to an Asahi shimbun poll, the proportion of people supporting the Japanese military legislation enacted in 2015 increased from 34% in March 2016 to 41% in March 2017. Meanwhile, the proportion of people who considered this law unconstitutional decreased significantly from 50% to 40% (and in just one year!).

We can see how, in the minds of the Japanese people, the permissible sphere of Self-Defence Forces activity under the current constitution has steadily expanded over time. In the postwar period, Japanese people have “confirmed” each shift in the government’s security policy. Then, once that security policy status quo is affirmed, the voters (who are not particular about the constitution) interpret the policies as being acceptable under the current constitution.

Rather than constitutionalism, we might even see a back-to-front situation here where voters think, “If the security policies implemented by the government are like this, we should read article nine in this way.” This voter way of thinking, in the sense that voters have given their seal of approval to government defence policies after the fact, has contributed to the stability of Liberal Democratic Party administrations. On the other hand, the fact that a sense of contradiction between the wording of the constitution and actual policy has not become an issue in society has helped make the LDP’s policy to revise article nine a more distant prospect.

Is this now the end of the “post-war”?

Japanese people in the postwar period have certainly not considered the constitution some kind of inviolable document. Yet, conversely, most people do not dislike it so much that they have a burning desire to revise it. Since the high growth period at least, most voters have not shown a strong interest in the constitution and have not been particularly fussy about how it is written or interpreted.

No political force that has come before this electorate has able to gather sufficient support by making the constitution a political issue. As a result, there has never been any revision of the wording of the Japanese constitution; instead, there has been a piece-by-piece (albeit with ex post facto approval from the people) broadening of its interpretation.

At the level of the elites, meanwhile, both advocates of constitutional revision and of protecting the constitution have continued to be more and more dissatisfied with the contents of the constitution and how it is applied. Rather than fading away, as time goes on the contentious issue of the constitution has become more acute. What’s more, the existence of this point of contention has continued to be a significant cause of division among the opposition, and as a result has created an underlying structure to postwar politics in which conservative parties have the electoral upper hand. The current opposition between the political parties that we should call the “Neo 1955 System” may be considered a political situation that appeared inevitably as a result of the conditions in society mentioned above.

We should note that the weak awareness of the constitution on which this is based is a result (as well as a cause) of the constitution issue being left unresolved. For a long time now, a situation has existed where actual policy contradicts the wording of the constitution; and for as long as this has not caused any visible harm, it is not impossible that most voters have accepted the situation and that, by extension, their concept of constitutionalism has been weakened. To put this another way, as long as no visible harm (the destruction of the constitutional system?) occurs as a result of continuing to leave the constitution issue unresolved, voters will not by themselves become more concerned with the constitution.

Perhaps there is a chance that before that day comes the elites will take the lead and bring the constitution issue to some kind of conclusion. In general terms, as long as voters are not particularly attached to the constitution, politicians do not need to worry too much about electoral gains and losses, and should be able to debate this issue. If this is recognized, perhaps surprisingly, they might be able to find common ground, even in current Diet debates. Should this happen, perhaps not only the wording of the constitution would change, but also the form of postwar Japanese politics itself.

Translated from “Tokushu: Kenpo kaisei no shonen ba—Yoronchosa kara yomitoku Nihonjin no ‘Utsurigi’ na kenpo-kan: Kaisei-rongi de yomigaeru ‘Neo 55 nen taisei’ (“Special Feature: A critical time for the constitution–Decoding public opinion polls to understand the Japanese people’s fickle attitudes towards the constitution: A look back at the constitutional revision debate and the ‘Neo 1955 system’”),” Chuokoron, May 2018, pp. 76-87. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [September 2018]

[1] Kitamura Takashi, “How rigid is Japan’s constitution?” Ho-seiji-kenkyu, volume 3, 2017

[2] An early example of this is the following statement by the constitutional scholar Kobayashi Naoki. “[Regarding the new draft constitution] while surprised at its unexpected progressiveness, a majority of the ordinary people welcomed democracy/pacifism with an open heart, and generally expressed a very positive attitude towards it. [The results of the Mainichi shimbun survey] clearly demonstrate that the government draft was supported by the majority.” (“An Analysis of Constitutional Developments in Japan,” Iwanami Shoten 1963, page 59)

In recent years, Kato Norihiro wrote the following based on the survey. “The ordinary classes of Japanese society (?) or normal people accepted the war renunciation article with unexpected equanimity, and an overwhelming majority welcomed it.” (“An Introduction to the Post-war,” Chikuma Shoten, 2015, page 353)

[3] On this point, it is probably true that the 1950s were an exception. In the mid-1950s, Ronald P. Dore surveyed Japan’s rural villages and recorded that nationalism, patriotism and arguments for re-militarization remained strong in society. Politicians from the conservative parties put emphasis on rural villages and Dore interpreted their advocation of constitutional revision and re-militarization as meaning it was advantageous to their electoral strategy. (Ronald P. Dore, Japan’s Rural Reforms, translated by Namiki Masayoshi, and others, Iwanami Shoten, 1965, p. 351 to 352.

[4] Waseda University, Survey on Japanese Social and Political Attitudes in the 21st Century.

Keywords

- constitutional revision debate

- Neo 1955 system

- public opinion polls

- article nine

- Self-Defence Forces

- overseas dispatch of the Self-Defence Forces

- peacekeeping operations

- right of collective defense

- Constitutional and Unconstitutional