Prime Minister Abe Shinzo Heads into Third Consecutive Term as President of the Liberal Democratic Party (Part 1) – The Two Faces of the Abe Administration: Can the Divergence Be Stopped?

Key Points

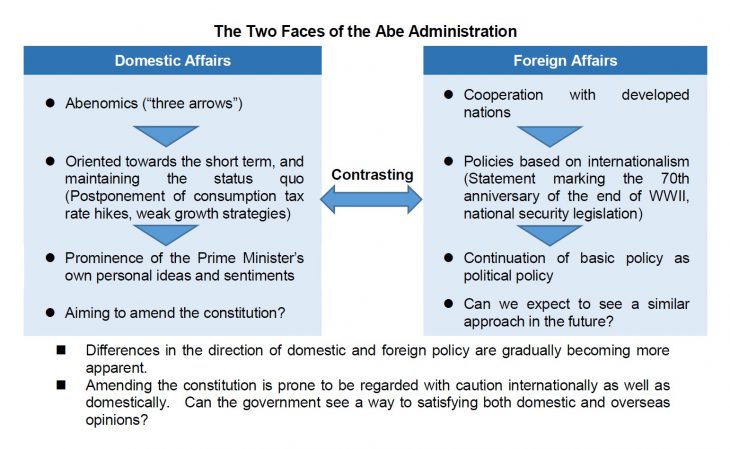

- There are noticeable differences in the administration’s “two faces” in handling domestic and foreign affairs

- The administration has lost its unity/cohesion since the second half of his second term

- They must show us a way to a sustainable economic structure and social security system

Prof. Machidori Satoshi

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo defeated LDP Secretary General Ishiba Shigeru in a recent leadership election to achieve his third victory and secure his position as Party President for a third term. The only others to have won three or more leadership elections in the past (even including uncontested reelections and extensions of term) are Ikeda Hayato, Sato Eisaku, Nakasone Yasuhiro and Koizumi Junichiro; all prime ministers who built and defined their generations.

If things continue smoothly as they are, Prime Minister Abe’s current tenure as Prime Minister will continue until September 2021, having lasted a total of just under nine years, and his numbers of consecutive days in office and total days in office (including his very first term as Prime Minister) will be the longest of any Prime Minister in the history of Japanese constitutional politics.

Despite being such a long-standing administration, I feel that it is still largely unclear how Japanese society has changed during “the era of the Abe administration,” or the “Abe era.” I wonder why that is.

Maybe the greatest reason is that, in contrast with its stable and consistent-feeling approach to foreign diplomacy, the administration has lost sight of its initially clear and comparatively unambiguous key foundation with regard to policies on domestic affairs. The Abe government has two faces, one for domestic affairs and one for foreign affairs, and the differences between the two are becoming gradually larger and more noticeable. (See figure.)

On the domestic front, at the time of the formation of the Second Abe Cabinet at the end of December 2012, the administration had a clear policy, of seeking to achieve economic regeneration through the economic policy known as Abenomics. Regardless of criticisms with regard to the content and direction of this policy, the administration boldly implemented fiscal stimulus and monetary easing, followed by efforts to reform the country’s socioeconomic structure as a growth strategy. The way in which they did this gave many voters hopes and expectations for the future.

However, the administration was reluctant to push ahead with the third arrow of socioeconomic reform. Instead, they shifted to a policy of seeking to ensure temporary buoyancy for their administration through a series of snap general elections over short periods of time. The circumstances surrounding this were probably that there was a need to secure political resources by winning those general elections in order to drive through security legislation and other bold policies on the foreign diplomacy front.

As a result of continuous moves that were overly biased towards the immediate situation, however, it cannot be denied that it has become unclear what the administration wants to do in the future with regard to Japanese society and the economy.

This point relates closely to what the Abe administration will aim to do over the next three years.

In the leadership election, Prime Minister Abe emphasized that the biggest theme of his third term will be amending the constitution to clarify the existence of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). Taken at face value, by emphasizing this point, the Prime Minister probably envisages a scenario of strengthening his unifying power through his victory in the leadership election and using this to push forward with constitutional amendment.

By doing so, he will essentially be repeating a pattern that has continued since around 2015 in the administration’s foreign diplomacy and national security policy.

But does this match up with the expectations of voters? According to the results of a public opinion poll conducted by The Nikkei newspaper, many are of the opinion that there is no need to hurry constitutional amendment to the extent of the timetable that the Prime Minister is envisaging. While there are by no means a shortage of voters who believe that a reform to the constitution is desirable, they do not rank it so highly in their list of priorities as domestic issues such as the economy and social security.

Moreover, if Japan is to emphasize a stance that places importance on international order with a key focus on liberalism, in an age where developed countries are prone to introverted thinking, as demonstrated by US President Donald Trump and his administration strengthening their slant towards conservatism, then it is necessary to accompany this with domestic reforms aiming to create a society commensurate with that image; one that is open and enlightened, and which values diversity. But the comments of certain ruling party members—and the response of the party leadership to those comments—leave some doubts as to the government’s awareness with regard to this point.

Today, the Office of the Prime Minister plays a major role in the policymaking process, and in cases where the intentions of the Prime Minister and trends in public opinion diverge there is a need for the Chief Cabinet Secretary to take a central role and make adjustments within the administration.

It has been widely known since long ago that Prime Minister Abe has conservative political beliefs, and that he has a strong interest in constitutional amendment. The reason why this has not so far become a priority issue for the administration, and why emphasis has instead been placed on economic policy, was that appropriate adjustments have been made within the administration itself.

In other words, the so-called Abe regime has not been based so much on the sole leadership of the Prime Minister himself as by that of the Office of the Prime Minister, or—to put it another way—based on the fact that the government was a unified administration. There is a strong possibility that the high approval rating which the Abe administration was able to maintain into the first half of 2017 did not represent a resonance of public opinion with the Prime Minister’s personal political stance, but literally support for the “administration” itself.

That unity within the administration has been lost since the second half of the Prime Minister’s second term, and it appears that adjustments to the government’s list of political priorities based on that unity have also ceased to be carried out appropriately.

Accordingly, the question of to what extent Prime Minister Abe can recover the unity which existed into the first half of his second term and create a priority ordering of policies as a unified administration will surely be a major key in determining what results he will be able to achieve in his third term. If the Prime Minister’s ideas are too prominent, and an appropriate priority ordering placing value on domestic reform cannot be achieved, then there is a risk that these three years will become a decisive period of “lost time” for Japanese society and the Japanese economy.

At the same time, activities with a view to the “Post-Abe” period to come three years down the line will surely become more energetic. The assessment made by many is that confrontation and disputes within the LDP over what course the party should take will cease to occur, and that leading/influential politicians who are fit to play leading roles in the next generation are not being fostered. But a more mysterious thing is that as long as the LDP continues to win elections under the Abe administration, opponents are appearing from within the party itself, and the movement to oppose the course being taken by the current administration is becoming stronger. The end of the Abe administration is now clearly in sight, and now is the beginning of a period of preparation for the new era to come.

The question now is, how will the government maintain a free and vibrant society in the face of the wave of international protectionism and the domestic issues of declining birthrate and population aging.

Recently, too, there are signs of policy changes, such as the government’s proactive policy towards accepting foreign laborers for what is referred to as “simple” or “unskilled” labor. But this policy has not been advanced in the form of the administration leading the debate and showing its determination head-on. For this reason, this policy change has ended without leaving a lasting impression upon many voters. The question is whether or not the government will continue with this way of doing things.

One possible approach would be to fly the flag of structural reform high, as the Koizumi administration did. Conversely, politicians may also appear who continue to maintain the status quo for as long as possible and follow a path of gradual decline, while at the same time aiming to create a more mature nation. It will be important for politicians aiming to make their mark in the Post-Abe era to clarify their respective stances and to appeal to voters through debate.

We must not forget that the turn of the opposition parties may also be to come. At present, center-left factions—which seek to actively advance a policy of redistribution while maintaining economic international competitiveness—are in a predicament, globally, in that they are unable to offer any realistic policy choices. Additionally, since in Japan’s case the relationship between The Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) is not a good one, these center-left factions are being marginalized to an even greater extent.

However, as became evident with the Moritomo Gakuen and Kake Gakuen scandals, the suspicion that the long-standing administration is creating exclusive vested interests is beginning to spread amongst voters.

In order to ensure that this does not lead to the emergence of populism as in other developed countries, it will be essential for the opposition parties to propose policies that will enable them to take up the challenge of forming a new administration.

There are high probabilities that the economy will take a downturn after the hosting of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games, and that social security costs will increase further in 2025 with members of Japan’s baby boom generation reaching the age of 75 and above. Building a sustainable economic structure and social security system before these events is a pressing issue.

It may not be possible to achieve this with policies that are supported by all voters. However, the greatest value to the existence of a stable long-term administration is in tackling difficult but essential issues by making full use of voter confidence. If we lose sight of this, then three years from now may not only mark the end of the Abe administration, but potentially also the beginning of a serious crisis for Japanese politics.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 3 July 2018 under the title, “Abe shusho, Jimin Sosai sanki-me e (1): ‘Futatsu no kao’ kairi tomerareruka (Prime Minister Abe Shinzo Heads into Third Consecutive Term as President of the Liberal Democratic Party [Part 1] – The Two Faces of the Abe Administration: Can the Divergence Be Stopped?).” The Nikkei, 3 July 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Abenomics

- three arrows

- consumption tax rate hikes

- Policies based on internationalism

- constitutional amendment

- JSDF

- Post-Abe

- foreign laborers

- sustainable economic structure

- sustainable social security system