Employment policy issues in light of Abenomics: Aims of the policy to raise the minimum wage and negative scenarios

Genda Yuji, Professor, University of Tokyo

Context for the increase in the number of workers during the Abe administration

Prof. Genda Yuji

In response to the end of the second Abe Shinzo administration, the longest serving cabinet in the history of constitutional government in Japan, newly appointed Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide signaled that he would continue the policies of the previous administration.

On August 28, 2020 when then Prime Minister Abe held a press conference to announce his unexpected resignation, he cited the increase in the number of workers as part of his self-assessment of the administration.

In actual fact, between 2012, when Abe became prime minister for the second time, and 2019, before the spread of COVID-19, Japan as a whole recorded a substantial increase of 4.44 million workers (Labour Force Survey” by the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications).

Previously, the number of workers had decreased by 2.77 million between 1997, when the number of workers peaked, and 2012. This suggests that the second Abe administration straight away recovered the employment opportunities that had been lost during the long period of economic stagnation, the so-called “lost decade.”

If we break down the figures, we find a substantial increase in employment for women and the elderly since 2012 with 3.34 million women and 2.96 million workers aged sixty-five or older in the workforce. It is said that the second Abe administration, which won every election it fought, was successful because it focused on issues directly linked to the daily lives of many citizens, such as the economy and job recovery, rather than on abstract political ideas and its long-cherished opinions on constitutional amendments. Employment policy is also an important agenda item for the Suga Cabinet, possibly because of the lingering effects of the pandemic.

But is the Abe administration really to be commended for the increase in the number of workers?

At the press conference mentioned earlier, Prime Minister Abe said, “In politics, the most important thing is to deliver results.” But even if the increase of more than four million workers is fact, is it not possible that the reasons are found elsewhere?

Where politicians look for results, academics look for reasons. In this article, I will assess the achievements of the former administration with regard to employment from the perspective of the reasons and context for the expanding job opportunities. I will also discuss some of the challenges for the new administration.

Abenomics and employment policies

The increase in the number of workers was due to a complex set of factors at work during the second Abe administration. There are at least four reasons.

Firstly, there was the effect of Abenomics, which was put forward when Prime Minister Abe took office. In cooperation with the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which welcomed a new governor in 2013, surprisingly expansive monetary policies were implemented in rapid succession based on the “three arrows” launched at the start of the administration. As a result, the economic situation took a turn for the better with improvements in exports when the ongoing trend for a strong yen was corrected. The government put together a budget with economic stimulus measures on a scale of ten trillion yen and its fiscal policies had a substantial impact on demand creation.

The jobs-to-applicants ratio, which hit rock bottom after the worldwide financial crisis in 2009 caused by the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, had already started to show signs of recovery and was rising. The ratio remained above 1 for the whole period from November 2013 to August 2020 when Abe announced his retirement.

It is appropriate to attribute some of the increase in the number of workers to Abenomics as corporations expanded job offers due to these economic policies.

Secondly, even if the government policies had results, it is possible that employment policies were more important than the monetary and fiscal policies.

Enacted in fiscal 2013 during the term of the administration, the revised Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons, which made it mandatory to guarantee employment opportunities up to the age of sixty-five, had a major impact on expanding employment opportunities for the elderly. In 2012 before the Act was enforced, the proportion of workers in the 60–64 age bracket was 57.7%, but by 2019, the proportion had risen by ten percentage points to 70.3%. The revised Act not only expanded employment for workers aged up to sixty-five, it was linked to a large increase in the number of elderly workers and it also became a valuable path to employment for workers who wished to stay in employment after age sixty-five.

However, if we look at the particulars, all these revisions are the result of the efforts of many stakeholders among government, labor unions, and employers over a long period of time leading up to 2012. The persistent arguments by labor unions and management and the careful design of the legal system by the government began to show the way before the second Abe administration was formed. In that sense, it would be more natural to think of the expanding job opportunities for the elderly as bearing fruit during the administration. (Further revision of the Act to make it mandatory to make efforts to secure job opportunities up to the age of seventy will be enacted after fiscal 2021. This is an initiative of the former administration).

It is also possible that employment policies intended to support those who balance work with childcare had a solid effect on expanding job opportunities for women. But, the revised Act on Childcare Leave and Caregiver Leave was enacted in 2010, so it can hardly be considered an achievement of the Abe Cabinet. This is another example where the Abe administration has benefited from an opportunity to show off the results. (The Act on Child Care and Caregiver Leave was also revised in 2016 and 2017 during the Abe administration.)

Incidentally, whether or not the employment policies of the Abe Cabinet contributed to the increase in productivity is being questioned at every turn. The website of The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) grandly proclaims, “Businesses that have improved labor productivity will be given more employment-related subsidies” and lists a large number of subsidies. Policies that focus on raising labor productivity will probably be strengthened rather than toned down by the Suga Cabinet. Whether to regard the policy as an opportunity to improve labor market efficiency, or as a cold shower for corporations and persons who are unable to increase productivity for various reasons is where assessments of the significance and role of employment policies differ.

The impact of long-term depopulation

Other than the outcome of a government policy, there may be a third reason behind the substantial increase in the number of workers during the second Abe administration. It is the impact of long-term shifts in the population such as the ongoing depopulation and the aging population.

In Japanese society, depopulation began in earnest at the start of the 2010s. Once the population aged fifteen and older passed its peak in 2011, the segment of the population aged under forty decreased by 4.86 million by 2019. The substantial decrease in the relatively young age bracket increased the rarity value of that age bracket, and stimulated improvements in working conditions and the working environment. For example, unpaid overtime in the service industry and sexual harassment, commonly accepted in some sectors until the early 2000s, were no longer permissible.

This also presented women who had been constrained in their ability to work with an opportunity to overcome barriers. By the 2010s, it had also become clear that the workplace would not operate without the contributions of women. As a result, there were substantial and overall improvements in the employment rate for women in their forties increasing by 1.09 million workers from 2012 to 2019. Although boosted by policy, this would not have happened without demographic change.

During the same term, workers aged sixty-five and older also increased by nearly three million, but here, the rise in the elderly population had a direct impact. Though elderly, many people are confident about their health and motivated to continue working, which is directly linked to an increase in workers. The presence of elderly people with a positive attitude to employment also became a major conduit for the expansion in job openings focused on non-regular employees.

Ultimately, major aspects of the employment increase were linked to the ongoing demographic change, which picked up speed at the start of the 2010s. The impact of factors due to changes in the population structure should be assessed in a way that is clearly differentiated from man-made policies.

Working to make ends meet

Lastly, the fourth reason is the possibility that insufficient income and inadequate social security have reinforced a situation where people who struggle to make ends meet have no choice but to work.

Women and the elderly, who have contributed much to the expanding job opportunities, account for a fair share of non-regular employees. Whether married or not, insufficient household income means that employment is a given for relatively young women of the employment ice-age generation. Many elderly people do not have sufficient savings for their old age as other generations did in the past because of a drop in income due to the protracted recession since the Heisei era. Since it is difficult to survive on the state pension alone, the reality is that they have to continue working.

I served as one of the editors of Kiki taio no shakai kagaku (Social Sciences of Crisis Thinking) where Dr. Osawa Mari (Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo), who specializes in comparative gender analysis of social policies, identified this point. Dr. Osawa criticized the second Abe administration for neglecting to update the social security system to a twenty-first century model, and basically keeping the 1970s model without breaking away from the conventional system. The several data tell us that distribution is working in reverse under the current system in Japan where households with higher-income and full-time homemakers are given favorable treatment, while dual-income households with low earnings, single mothers, and other households are punished.

A situation has been created where people who have difficulties making ends meet are forced to work because they cannot live comfortably due to the failure of the income redistribution function of social security. If the increase in the number of workers is blindly touted as an achievement for the former administration, while the new administration continues with the same goals without reviewing the facts, it is likely that a significant portion of the public will feel dissatisfied and uncomfortable.

Employment bipolarization

Although the number of workers increased during the former administration, critics claim that the majority of these workers were in insecure, non-regular employment. But, this is not necessarily the case.

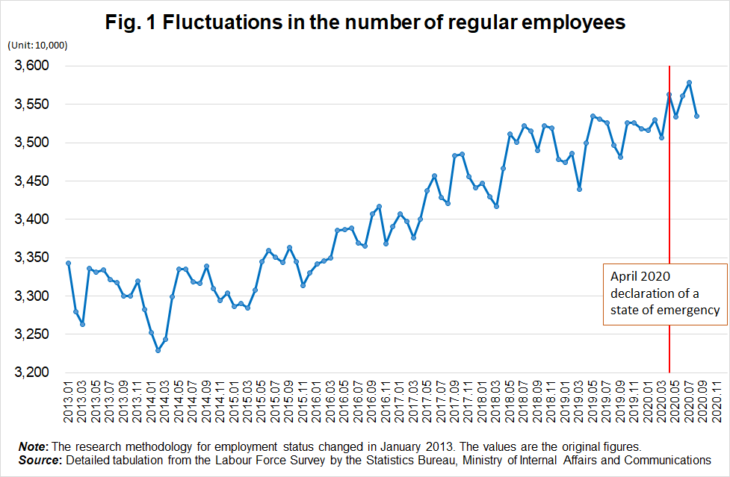

Figure 1 shows fluctuations in the number of regular employees in recent years. As is apparent at first glance, the number has risen steadily since early 2014. This is not emphasized in the press, but in April 2020, when a state of emergency was declared due to the spread of COVID-19, regular employees numbered 35.63 million, the highest figure recorded since 2013. Even five months later, there is as of yet no significant downward trend in the number of regular employees.

From the long-term perspective, the average number of regular employees in the April to June period in 2020 was 35.43 million, which is the highest level since the April-June period in 2002 (The Labour Force Survey, detailed tabulation). The decline in full-time employees, which has continued since 2000, made a V-shaped recovery during the second Abe administration.

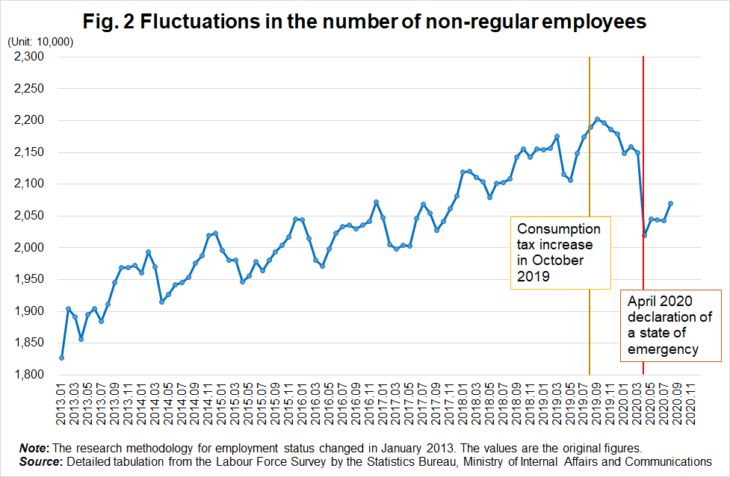

On the other hand, the increase in the number of non-regular employees has, of course, outpaced the increase in regular employees as indicated in Figure 2. Whereas regular employees increased by 1.49 million from 2012 to 2019, non-regular employees increased by as much as 3.49 million.

Incidentally, the bullish rise in non-regular employees actually peaked in September 2019 immediately before the consumption tax increase and had already started to show a downward trend. Approximately half a year later, more than one million non-regular employees were lost in a mere month from March to April when COVID-19 was out of control.

Not limited to the economy alone, year-on-year changes are normally the focus of attention as indicators of a particular situation. However, even if the heat in one year was on a par with previous years, a comparison with the immediately preceding year may create the impression that the year in question was comparatively cool if the preceding year was extremely hot. Therefore, weather forecasts generally compare the temperature to an average year, meaning the average temperature over the past thirty years.

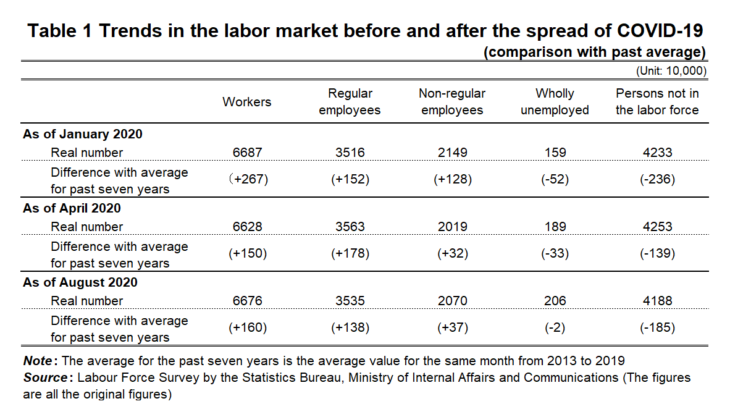

Although not extending as far as the past thirty years, we tried to assess the employment situation before and after the spread of COVID-19 based on a comparison with the average level for the seven years from 2013 to 2019, which nearly overlap with the second Abe administration. The results are shown in Table 1.

In January 2020, immediately before the spread of COVID-19, the employment bonus, which indicates the extent of employment improvement compared to the previous seven-year average, was accumulated for 2.67 million workers. With regard to employment bonuses, full-time employees already exceeded non-regular employees at the time with 1.52 million regular employees to 1.28 million non-regular employees.

By April when COVID-19 had spread, approximately one million employment bonuses for workers and non-regular employees had disappeared in a short period of time. Meanwhile, bonuses for regular employees had increased by more than one month. At the time of writing, the latest figures of August 2020 indicate that the structure remains the same with regular employees retaining most of their bonuses despite a slight weakening.

As of January, the number of the wholly unemployed remained unchanged at 520,000 persons below the seven-year average. By April, the gap had shrunk and by August, the number was approaching the seven-year average. By the start of the new Cabinet, the advantage of a low number of unemployed during the Abe administration had almost disappeared.

In January, the number of persons not in the labor force had dropped to 2.36 million below the seven-year average in response to the plan to promote the dynamic engagement of all citizens. By April, the gap shrank as an increasing number of people stopped working as COVID-19 spread. While participation in the labor force had resumed by August, many people are still hesitant about returning to work due to COVID-19 and other risks.

The new Cabinet has had a difficult start in terms of employment amid an increasing bipolarization where regular employees have access to stable employment opportunities, while non-regular employees and the unemployed are under increasing pressure.

Focus on the minimum wage

On October 6, 2020, the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy held its first meeting since the start of the Suga Cabinet. Reference materials submitted by one of the expert members, Niinami Takeshi, contains a proposal to raise productivity by promoting DX (digital transformation) as a trigger to raise the national average minimum wage to 1,000 yen. Other reference materials jointly submitted by expert members suggest that companies that have exited the market have consistently forced down productivity.

The underlying claim is that encouraging companies with generally low productivity to exit the market should boost the productivity of the economy as a whole. Enjoying the tailwind of such arguments, it seems that it is the ambition of the new Cabinet to make its name by raising wages significantly, which the Abe administration ultimately failed to do, and to break away from the accompanying deflation. Keeping in mind the Lower House elections, a substantial increase in the minimum wage next year may emerge as a winning ticket.

Had it not been for the spread of COVID-19, the minimum wage was expected to increase significantly across the country in 2020 reflecting the unprecedented labor shortage. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been widespread concern that a significant decrease in the number of job openings would destabilize the employment situation, so the increase in the regional minimum wage was limited to forty prefectures and the amount of increase was limited to one to three yen.

If the spread of COVID-19 has been halted and if there is a certain level of job retention by spring in 2021, it is expected that the Prime Minister’s Office will issue a major order to speed up the preparations to raise the minimum wage across the country. One example might be to promote subsidies for business improvement to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and small businesses trying to raise the lowest wages.

This has the potential to be welcomed by non-regular employees who struggle to make ends meet on low wages. Even if a wage hike means that running a business is not feasible for some companies and the number of business failures increase, the surviving companies may strengthen new investment and other management strategies, and improve their productivity to meet the higher labor costs associated with the increase in minimum wage. If so, the benefit of a raised minimum wage could conceivably extend to regular employees.

Prudent shock therapy

However, it must be remembered that such a scenario for the increase in the minimum wage is the ideal. In reality, if there is an increase in corporate bankruptcies, large numbers of people may lose employment opportunities, and the majority is likely to be non-regular employees who were working for an hourly pay just around the minimum wage. There should also be proposals for a set of policies to strengthen job training and other skills development to enable displaced workers to earn a high wage. However, it takes time for the effects of training to emerge and there is potential for long-term unemployment among the young age brackets in regions where many people are unable to move to urban areas where jobs are plentiful.

To avoid such a serious situation, the government should be cautious about administering the shock therapy of major increases in the minimum wage across the country unless there are indications that moderate labor shortages will be sustainable in the foreseeable future. If there is a labor shortage, people who lose their jobs because of wage increases will find new jobs relatively quickly, which will to some degree suppress the side effects.

As a rough guide to moderate labor shortage, we have to make the firm assumption that the average jobs-to-applicant ratio for the country as a whole will be maintained at the 1.0 to 1.2 level, and that the ratio in most prefectures will be above 1.0. According to the statistics at the time of writing, the jobs-to-applicant ratio for the whole country is 1.04 (August 2020), and although the ratio has more or less remained at 1.0, twelve prefectures are already below 1.0 on a workplace basis (seasonally adjusted). Dark clouds are already starting to gather over the proposal to increase wages across the board.

Many labor market trends cannot be controlled by policy alone. I expect that the new administration is fully aware of this and will take a prudent approach to policy management.

Translated from “Abenomikusu sokatsu kara mieru koyo seisaku no kadai: ‘Saitei-chingin hikiage’ saku no nerai to fu no sinario (Employment policy issues in light of Abenomics: Aims of the policy to raise the minimum wage and negative scenarios),” Chuokoron, December 2020, pp. 46-53. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [January 2021]

Keywords

- Genda Yuji

- University of Tokyo

- Institute of Social Science

- employment policy

- labor force

- job opportunities

- Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons

- Act on Childcare Leave and Caregiver Leave

- depopulation

- demographic change

- social security

- employment ice-age generation

- employment bipolarization

- non-regular employees

- full-time employees

- unemployed

- COVID-19

- minimum wage