The Kishida Administration’s Challenges after the Upper House Election: Fiscal and National Sustainability Restructuring

Poster board of candidates for the 2022 Upper House election in Ikebukuro, Tokyo.

Photo: Ryuji / PIXTA

Taniguchi Masaki, Professor, University of Tokyo

Key points

- The impact of Abe’s absence on the administration is uncertain.

- Leaving government debt and population decline unchecked will be fatal.

- There is an urgent need for the CDPJ to restore trust in its economic policies.

Prof. Taniguchi Masaki

Media coverage reported that the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was in the lead from the beginning of the election, and the results were generally as expected. But the shooting of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, which occurred two days before election day, sent shockwaves through the domestic and international communities. Even if the motives were not political, this heinous act undermined Japanese democratic politics and as such should be categorically condemned.

The impact of the tragic events will be reflected in post-election politics. As a hawkish debater, Abe led LDP conservatism from the mid-2000s.

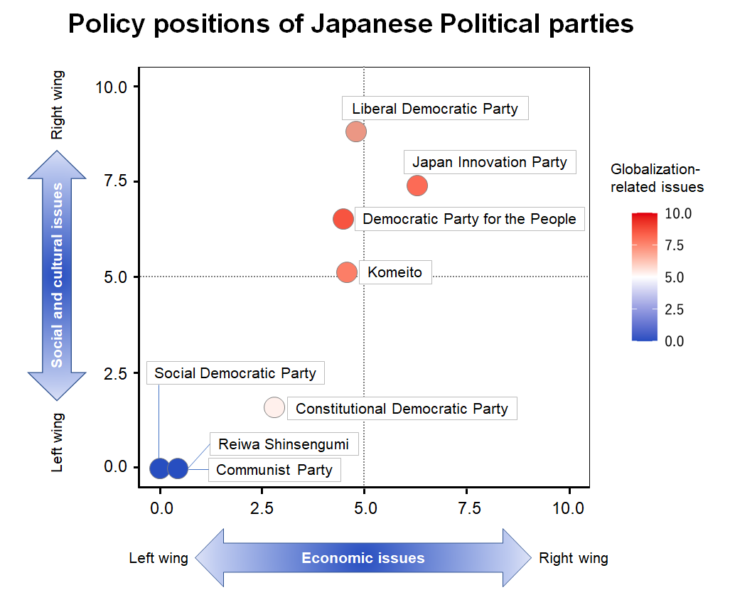

The figure shows the policy positions of political parties based on evaluations by experts in national politics. In the vertical axis of social and cultural issues, the LDP is positioned at the top; that is, it is one of the most right-wing political parties in the world. At the same time, it is a testament to the LDP’s commitment to maintaining a socio-cultural conservative line, which might explain why any growth of right-wing populist parties as seen in European countries has been suppressed. Rather than criticizing existing political parties and establishing new parties, pursuing policy implementation within the LDP can ensure more influence.

Source: Nippon Institute for Research Advancement (NIRA)

Prime Minister Kishida Fumio’s responses to a candidate survey conducted during past elections show no major differences from the responses of former prime ministers Abe and Suga Yoshihide, so it is doubtful whether Kishida can be called a moderate conservative. Yet there is a growing impression that Prime Minister Kishida is distancing himself from Abe, based on the facts that [Kishida] is the leader of the Kochikai faction that has produced former prime ministers Ohira Masayoshi (1910–80) and Miyazawa Kiichi (1919–2007), that he denied Abe’s passive attitude toward fiscal consolidation and rejected his proposal that the Big-Boned Policy (Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform), which was approved by the Cabinet in June, be written to increase defense expenditures to 2% of GDP, and that he disagreed over whom to appoint as Administrative Vice-Minister of Defense.

In this Upper House election, there were a number of political parties with radical right-wing claims, and the fact that some of them won seats, as the Sanseito party did, may be seen as a kind of reaction to seeing Kishida as a moderate.

Within the LDP, Abe was the biggest backer for conservatives and proactive fiscal advocates, and he was also a key person who could restore order in the party simply by calling “cease fire!” It will take some time before we can gauge what impact the absence of that conservative heavyweight and leader [of the Abe faction] will have on how Prime Minister Kishida runs his administration.

By doing their best to drive safely so as not to make a major mistake, the Kishida administration was able to make it over the triple hurdle that might be likened to a triathlon: the LDP presidential election and Lower House election in 2021 as well as the recent Upper House election. Going forward, it will be necessary to clarify the direction of their policy measures and then step on the gas.

Kishida has adopted “New Form of Capitalism” as his feature policy, explaining it as a shift from the neoliberalism that has persisted since Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s structural reform. However, Abe once described his own economic policy as “liberal.” Indeed, as can be seen on the horizontal axis of the figure, the economic policies of LDP governments for at least the past decade or so have been centrist by global standards, taking on a slight left, meaning social democratic nuance. Even if he insists on breaking away from neoliberalism, it is unclear to what extent he will be able to appeal to foreign countries and markets.

There is the view that a “golden three years” have started until the end of the current Lower House term in 2025, during which the LDP can work on policy measures without having to worry about elections. But if Kishida is keen to aim for re-election as the president of the LDP, he has to show that he is a president who won or can win in the next Lower House election, which means that he cannot afford to be complacent.

Starting with the Cabinet reshuffle and the appointment of LDP executives after the Upper House election, there is a host of political challenges that also includes dealing with current rising prices and the COVID-19 7th wave, maintaining relations with the Komeito party as their Chief Representative Yamaguchi Natsuo finishes his term this fall, revising the three defense documents (National Security Strategy, National Defense Program Guidelines, Medium-Term Defense Program), choosing a successor to Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Kuroda Haruhiko whose term expires next spring, and the G7 Hiroshima Summit.

In addition to responding to these issues, I expect the Kishida administration to make fair and honest efforts to address the fundamental problems facing Japan.

Unless you adhere to a minority standpoint like Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), you cannot tolerate a government debt of more than 200% of GDP. There is no getting around the issue of eliminating “a medium level of welfare for a low burden” in social security, especially medical expenses. With a declining birthrate and an aging population, long-term population decline is inevitable. If so, rather than each municipality competing for the dwindling number of residents like a game of musical chairs, it will be necessary to consider the sustainability of national territory and regions based on the premise of population decline as a given.

Even if they are not acute risks that immediately threaten people’s lives and property like disasters and incidents, they are progressive risks for Japanese society that will eventually become fatal if left untreated.

Before the Upper House election announcement, Kishida spoke about the declining birthrate and pointed out that “the middle class is struggling with issues of education and housing,” and also commented on fiscal consolidation by saying that “No matter how much we insist that ‘this is okay,’ we cannot maintain confidence unless we win the approval of the market and the international community.” These perceptions are quite correct. However, to solve these problems, it is necessary to make long-term and tenacious efforts that cannot be contained in the term of office of a single prime minister. I want Kishida to seek his own “political legacy” by taking the first step toward that.

On the other hand, in the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), President Izumi Kenta went for the orthodox method of seeking to showcase stable foreign policies that can take things over from the administration, for example by setting up a working team for national security strategy within the party while trying to differentiate themselves from the LDP. However, in addition to the fact that foreign and security policy remained the LDP’s forte also during the government period of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) [predecessor of the CDPJ] in 2009–2012, the growing interest in security policies following the Russian invasion of Ukraine had negative consequences for the CDPJ in the recent Upper House election.

Another challenge for the CDPJ is restoring voter trust in its economic policies, which it has lost since the DPJ went into opposition in 2012. In this regard, far from catching up with the LDP, it is trailing behind even the Japan Innovation Party (JIP), which has pushed its achievements in Osaka to the forefront. The better way to restore trust is likely to honestly state that to achieve good welfare, there are no free lunches and the burden has to be shared.

The CDPJ ought to possess the broad-mindedness and determination to credibly overcome policy divides, just like the British Labour Party did in the 1990s, when the party leader, Tony Blair (later British Prime Minister), who sought to position himself in the center of British politics, was supported by the deputy leader of the party, John Prescott, who prevented the left from rebelling by supporting Blair.

The Osaka-based JIP surpassed the CDPJ in terms of the number of votes received in the proportional-representation constituencies [in the recent Upper House election]. The next challenge is to develop a strategy to win power by appealing to voters across the country. If it is aiming for a change of government rather than to join the LDP-Komeito coalition government, the JIP cannot use the approaches it used in the past to implement policies in Osaka, like cooperating with Komeito in practice during the election or building close relationships with the then Prime Minister Abe and Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga in the central government.

At the national level, it will be difficult to [demonstrate the strength] it has done at home in Osaka and Hyogo Prefectures to keep the CDPJ down, and relations with the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) and their supporter labor unions are not very good, despite their centrism. Regardless of whether the success of JIP President Matsui Ichiro, who has announced his resignation, comes from Osaka or not, the new leader will be required to have a political strategy that goes beyond the conventional “nationwide expansion of the Osaka model.”

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 20 July 2022 under the title, “Saninsengo no Kishida seiken no kadai (I): Zaisei, kokudo no jizokukanosei, saikochiku wo (The Kishida Administration’s Challenges after the Upper House Election (I): Fiscal and National Sustainability Restructuring).” The Nikkei, 20 July 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Taniguchi Masaki

- University of Tokyo

- Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)

- Kishida Fumio

- Abe Shinzo

- Abe faction

- right-wing

- conservative

- moderate conservative

- populist

- New Form of Capitalism

- neoliberalism

- Komeito

- government debt

- birthrate

- aging population

- Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ)

- Japan Innovation Party (JIP)