Beyond an Age of Chaos: A Time to Rethink the Significance of Elections

In the phase of “democratic backsliding,” political polarization and electoral fraud are becoming more prevalent around the world. Election fraud, including repression, harassment, and vote tampering, is widespread.

Image: Dmitry Kovalchuk / PIXTA

Key points

- Elections are manipulated to stay in power in authoritarian countries

- Political division and growing electoral fraud also in democratic countries

- Administrations calling snap general elections when it suits them should also be scrutinized

Higashijima Masaaki, Associate Professor, University of Tokyo

This year, 2024 is a year with elections around the world. In addition to the United States and Russia, which have a major influence on international politics, national elections are also planned in regional powers such as Indonesia, India, Mexico, South Korea, Taiwan, and other neighboring countries and regions. Depending on the ongoing political funding issue, a dissolution of the Lower House and a general election may also be on the horizon in Japan.

Elections have long been synonymous with representative democracy. What are the implications of the upcoming elections in so many countries for the future of the modern political systems?

◆◆◆ ◆◆◆

Regardless of the political system, be it authoritarianism or democracy, national elections are conducted widely. During the Cold War, the test of whether or not multiple political parties competed in elections was the touchstone that separated the two systems. Nearly 80% of authoritarian countries now hold elections in which opposition parties participate.

At the beginning of the 21st century, when elections became semi-normative in authoritarian regimes as well, the future of democracy looked bright. This was because competitive elections are at the core of representative democracy, so there was an implicit assumption that the world will democratize as it spreads. At the time, Professor Staffan I. Lindberg of the University of Gothenburg and others argued that repeated multi-party elections would deepen democracy. The more elections are experienced, the more politicians and citizens adapt to and learn the election rules. They also come to accept political activities centered on elections as the norm. If elections become the norm, violently seizing power through coups or civil wars becomes less likely. It also improves the elements that make up a free democracy, such as freedom of association, independent media, and the rule of law. This theory of “democratization through elections” emerged from the experiences of African countries in the 1990s, where the dictatorships fell one after another, and was supported by analyses of data from 193 countries around the world from 1919 to 2004.

Ironically, however, since the mid-1980s, when the theory of democratization through elections was advocated, people’s distrust of politics has increased, and populist politicians have emerged. The democratic systems have become unstable, and we have entered a phase called “democratic backsliding.”

Meanwhile, in authoritarian countries that regularly hold elections, there has been an increase in politicians who skillfully manipulate elections to stay in power by means other than violence. The modern world has entered a new phase where retreating democracy and transforming authoritarianism intersect.

It is difficult to expect democratization through elections in this new era. Why have elections become unreliable as a means of deepening democratic practices?

◆◆◆ ◆◆◆

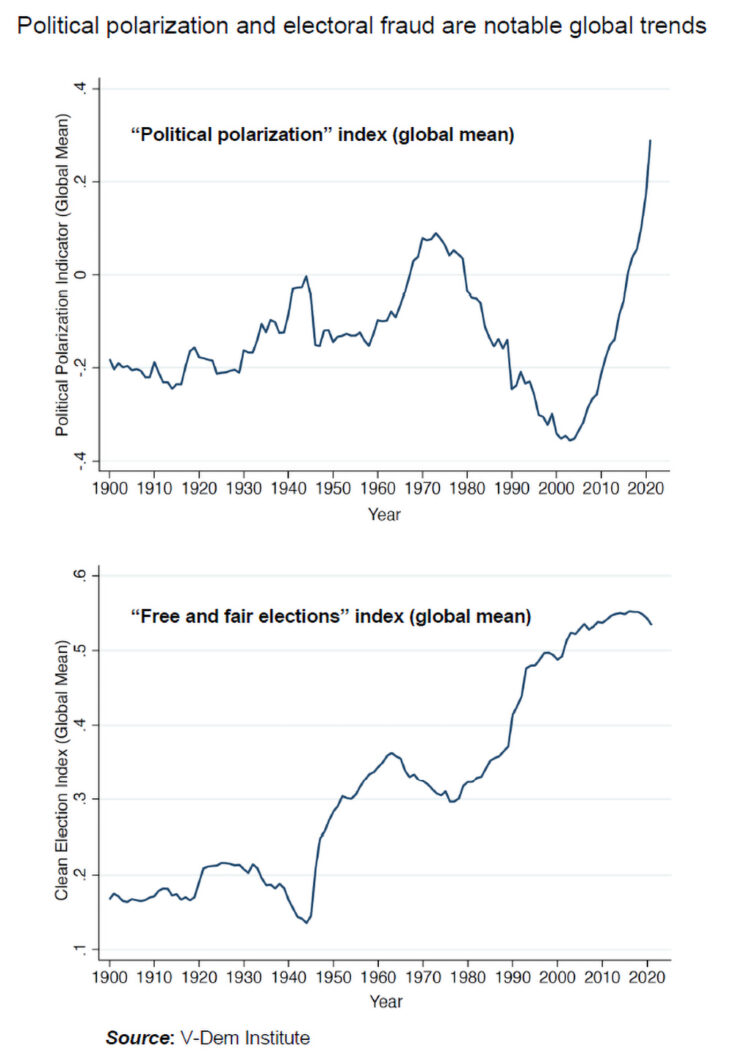

Firstly, voters are divided into two political factions, giving rise to “political differentiation” in which fierce conflicts of political beliefs also lead to differences in people’s behavior and opinions in social life. The Swedish V-Dem Institute’s “political polarization” index has risen rapidly since the mid-1980s and is now at its most serious level in the past 120 years (see figure).

An election is a mechanism by which power is fully delegated to the winning parties or politicians until the next election. Growing political polarization narrows the room for compromise among competing politicians. When the policies promoted by the winners of an election with whom one disagrees have a considerable impact on one’s own life, the cost of accepting an unfavorable election result and waiting until the next election increases. Politics conducted by elected representatives exacerbate conflicts rather than ease them. The rise of populist forces such as former US President Trump, Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary, and Poland’s “Law and Justice” party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) has always been accompanied by serious political polarization. Trump’s rejection of Biden’s victory in the 2020 US Presidential Election deepened the democratic dysfunction and exacerbated the political polarization. The November 2024 US Presidential Election could accelerate a vicious cycle of political polarization and electoral confrontation.

The second reason is widespread electoral fraud, including repression, harassment, and vote tampering. The V-Dem Institute’s “free and fair elections” index was stagnant since the mid-1980s but has deteriorated in recent years (see bottom figure).

Blatant election fraud by incumbent politicians undermines the legitimacy of the system. Associate Professor Ora John Reuter at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and others conducted a survey experiment after the 2016 Russian parliamentary election and analyzed how overt election interference under President Putin’s regime affected voters’ support for the regime.

They found that voters who received information that the candidate of the ruling “United Russia” had falsified or bought votes or harassed opposing candidates were less likely to support the regime than those who had not. The impact of decline in support was stronger among ardent supporters of the ruling party.

It is not hard to imagine that Putin, who has no choice but to invest considerable financial resources in the war in Ukraine, will try to win a landslide victory in the upcoming election through blatant fraud. How the election fraud is carried out and whether it undermines the stability of Putin’s regime should be one of the key issues in the Russian presidential election.

At the same time, policymakers recognize the costs of blatant election fraud and use clever means to distort election results. For example, one of the tools typically used in democratic countries is the arbitrary manipulation of election timing. In many countries, the power to call a snap election lies with the prime minister, so it is easy to use this as a tool to maintain power.

Professor Petra Schleiter at the University of Oxford and others analyzed parliamentary elections (1945–2013) in 27 European countries that have adopted a parliamentary cabinet system, showing that early general elections would boost the ruling party’s share of the vote and seats, increasing its chances of retaining power.

What matters here is that the election timing is manipulated in accordance with election law, so it is less likely to cause voter resentment than blatant election interference. Together with Kadoya Hisashi, Research Associate at Waseda University and Associate Professor Yanai Yuki, Kochi University of Technology, I statistically analyzed data of 340,000 voters in 58 democratic countries. The results showed that trust in the government and parliament did not diminish to a statistically significant degree even immediately after a snap election, even tending to rise in the long run.

The analytical results suggest that the formation of a stable majority by manipulating election timing promotes efficient policymaking and increases support for the government in the long run. However, winning elections through election manipulation that is difficult for voters to recognize is undesirable for healthy electoral development.

Looking at Japanese elections, opportunistic snap general elections have been a trump card of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Now that LDP politics seem to be at an impasse due to the political funding issue, the question is when the government will hold a general election. Voters’ political literacy will be tested to see if they can scrutinize the political motivations and carefully consider their voting behavior so that it contributes to the development of democratic politics.

Competitive elections are not a standard that separates democracy from authoritarianism in the modern world, nor are they a panacea for advancing democracy. Rather, they can arguably be called the cause of various problems in modern politics. At the same time, however, they are a political institution that cannot be avoided as long as we opt for representative democracy. How can we correctly recognize the limitations of elections and reform them? It is surely essential that we engage in open discussions that take into account diverse possibilities.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 8 January 2024 under the title, “Konton no Jidainosakini (III): Senkyo no igiwo toitadasu toki (Beyond an Age of Chaos III: A Time to Rethink the Significance of Elections),” The Nikkei, 24 October 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Higashijima Masaaki

- University of Tokyo

- elections

- power

- authoritarian regime

- authoritarianism

- democracy

- representative democracy

- opposition parties

- political division

- electoral fraud

- snap elections

- democratization through elections

- populism

- democratic backsliding

- political differentiation

- political polarization

- election timing

- Trump

- Putin

- LDP