A New Era of Michi-no-eki Takes Off! – Ever-evolving community hubs for local rejuvenation –

Michi-no-eki or the roadside station system was launched in 1993, and has since expanded nationwide to a total of 1,040 locations, with annual sales reaching 210 billion yen (as of fiscal year 2012). This nationwide initiative continues evolving as a spearhead for local rejuvenation efforts promoted by the government. The following article reports on the program’s current status and outlook based on discussions held between Ishida Haruo, professor of the Department of Social Systems and Management at the University of Tsukuba, and Hashimoto Goro, Specail editorial board member at the Yomiuri shimbun. (The discussions were held at the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo.)

The Michi-no-eki of the Ritsuryo period are reborn

Hashimoto Goro: It has been twenty-two years since the start of the project to install Michi-no-eki, or roadside stations. These are rest areas located along standard roads. They have become very popular spots, and there are 1,040 of them all over Japan today. What is the background behind this national program?

Ishida Haruo: The progress of motorization has resulted in an increase in the number of long-distance travelers and drivers, who need rest facilities after driving long distances. Traditionally, comfortable rest areas and other facilities including toilets were often lacking along conventional roads. Furthermore, there was no adequate coordination in place involving both road users and the local people living in the area to improve the situation. Given the circumstances, we proposed a concept of building stations along conventional roads that are similar to the ones installed along railway lines. We believed that they would serve as rest facilities for travelers and drivers, and furthermore as locations to promote communication between visitors and people living in the region. That is the background story behind the project for building the Michi-no-eki.

As a matter of fact, the historical origin of Japan’s station system goes back to ancient times, when it was used for roads. When an ancient trunk road network named the Shichido Ekiro (or public roads connecting the seven regions of Japan) was built during the Ritsuryo period, stations were established along the roads, at which things like messages, documents and goods were relayed from one person to another. In the years that followed, however, the function of the ancient road system was replaced by marine transport and railroads, and consequently Japan’s ancient road system with stations lost its reason for existence. However, after a long silence lasting centuries, the system has been reborn today as the Michi-no-eki.

Hashimoto: I believe that the Michi-no-eki or roadside stations of today are not merely rest areas with parking lots and toilets where local produce and goods are sold, but that they are more like our historical resources or a revival of the ancient system for the Ritsuryo period.

A further important function: a hub for disaster prevention activities

Hashimoto: Michi-no-eki have historical significance indeed, as you mentioned earlier. They also served as disaster prevention hubs at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Ishida: As they did after the Great East Japan Earthquake, Michi-no-eki demonstrated their capability to serve as hubs for disaster prevention activities in the wake of the Chuetsu Earthquake in 2004. Those who survived the disaster in the area and drivers gathered together at the roadside stations in order to exchange information and deliver relief aid and supplies to those who needed them, which demonstrated the significant function of Michi-no-eki as disaster prevention hubs. Given this experience, Michi-no-eki must have played a significant role at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, I believe. Michi-no-eki focus on sales of local produce brought in by farmers living near the facilities, which means that they offer a significant advantage in the event of a disaster as a distribution center of emergency food supplies.

Management with the original, creative ideas of the local people

Hashimoto: When it comes to performing relief activities in the wake of a catastrophic earthquake disaster, it is more important and effective to take a regional approach than a national-level approach, which is often criticized as being inflexible and bureaucratic. Have Michi-no-eki been effective in terms of this regional approach?

Ishida: Michi-no-eki are equipped with a minimum of 24-hour parking and toilet facilities. For the most part, daily operations are managed by the people living in the area with their original, creative ideas, and this has led to the success of Michi-no-eki, I guess.

Hashimoto: I believe that it is important for the people in the region to have clear and specific ideas as to how they wish to sustain and grow their local lives and economies in order for Michi-no-eki to become successful.

Ishida: Michi-no-eki have a wide range of roles as hubs creating vibrant local communities through collaborative efforts with the region, serving as a gateway to bring in more tourists, or as a local community center to support people’s lives in collaboration with the local town office and clinics. This has helped lead to the expansion of the facilities, which are now found in 1,040 locations all over Japan. With a centralized approach, Michi-no-eki would not have achieved such great success, I am afraid. That may be one of the major reasons why the concept of Michi-no-eki is attracting such a lot of attention today.

Designation as National Model Cases and other Cases with Significant Potential

Hashimoto: On January 30 in 2015, the Advisory Panel of Experts on Michi-no-eki chaired by you announced those roadside facilities serving as successful examples, with Michi-no-eki utilized as a hub to promote local rejuvenation efforts. Six stations have been designated as National Model Cases, with thirty-five other facilities chosen as Cases with Significant Potential.

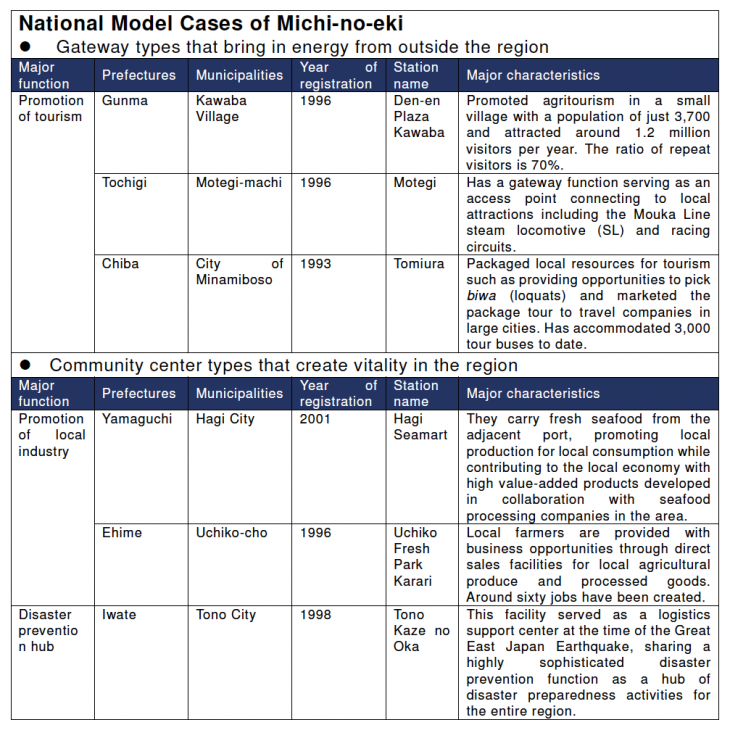

Ishida: Those designated as National Model Cases compare to Michelin’s three-star rating. We have categorized the National Model Cases into two types: gateway types that bring in energy from outside the region; and community center types that create vitality within the region. For the gateway type, three stations were selected: Den-en Plaza Kawaba, Kawaba Village, Gunma Prefecture; Motegi, Motegi-machi, Tochigi Prefecture; and Tomiura, City of Minamiboso, Chiba Prefecture. For the community center type, another three stations were selected: Hagi Seamart, Hagi City, Yamaguchi Prefecture; Uchiko Fresh Park Karari, Uchiko-cho, Ehime Prefecture; and Tono Kaze no Oka, Tono City, Iwate Prefecture. Den-en Plaza Kawaba attracts around 1.2 million visitors a year, as it has become popular as a destination, not just as a rest area.

Hashimoto: That is the point. Michi-no-eki are no longer places where people merely stop by; they are more like visitor destinations.

Ishida: Roadside stations such as Motegi and Tomiura also focus on sales of locally processed produce. These two facilities have also become destinations for visitors, with a high ratio of repeat customers. Furthermore, these stations contribute a great deal to the expansion of local employment and the regional economy, as most of the goods on sale are made in the surrounding villages and towns within the region.

Women are the main players in creating vitality and confidence in the region

Hashimoto: Yanagita Kunio, a legendary folklorist, lauded the powers of Japanese women in his book entitled Imoto no chikara (The Powers of the Sister). The powers of women

appear to be indispensable in order to promote regional vitality, and this holds true, not only with regard to Michi-no-eki.

Ishida: Women are now the main players in promoting the regional economies, creating vitality and confidence in the local communities, and this has been underpinned by the spread in the success of Michi-no-eki throughout the nation. A rural rejuvenation project was launched by the government late last year. The government aims to promote regional economies with initiatives combining agriculture and tourism, but its attempts have made little progress to date. Efforts to promote inbound tourism (attracting international visitors to Japan) do not seem to have paid off yet either in the context of rural rejuvenation. But the women working at Michi-no-eki (mostly housewives) have demonstrated that their work does indeed pay off. This type of successful experience must be communicated and shared more widely by many other people in a variety of local businesses, including tourism.

Women create vitality and confidence in the region. Michi-no-eki, Den-en Plaza Kawaba (Kawaba Village, Gunma Prefecture) |

Thirty-three types of original products have been developed. Michi-no-eki, Motegi (Motegi-machi, Tochigi Prefecture) |

Networking leads to a new stage of development

Hashimoto: Based on what you have told me so far, I assume that Michi-no-eki are doing very well in general. However, are there any issues that need to be addressed with respect to Michi-no-eki? If so, I wonder if you could elaborate on these.

Ishida: I am a little disappointed that there is a lack of effective coordination among Michi-no-eki facility operators, who have traditionally tended to manage facility operations independently with original and creative ideas.

Hashimoto: Do you mean that they are competing against one another?

Ishida: That’s right. Having said that, there are signs of new developments in this area. We are beginning to see new developments with respect to the Izu Michi-no-eki Network and the Shimanami Kaido Area Michi-no-eki. The Izu Michi-no-eki Network connects eight roadside stations (some are under construction) located on the Izu Peninsula, allowing

Significant potential for inbound tourism. Michi-no-eki, Arai (Myoko City, Niigata Prefecture)

them to share a wide range of information related to the regions where other stations operate so that it is possible to obtain information regarding other areas on the Peninsula provided by other stations in the network at any station. The Shimanami Kaido Area Michi-no-eki connects five stations in the region together, serving as a gateway to the Shimanami Kaido Cycling Course and a cluster of islands in the Seto Inland Sea. Any attempt like this is extremely important in order for the Michi-no-eki to play a role as connection points for the roads in a real sense. I believe that these cases with significant potential will evolve further, and I expect that they will come up with many more innovative ideas to attract international visitors and encourage them to stay and travel for longer within the region, while aiming to increase the ratio of repeat visitors.

Aiming to become a regional hub in a real sense

Hashimoto: I believe it is important for municipal governments as well as those living in the regions to have a clear idea as to how their Michi-no-eki will blend with community development initiatives as a whole, so that they can play a pivotal role in promoting local rejuvenation.

Ishida: I believe that municipal leaders are well aware of the importance of what you have just mentioned, as they are responsible for installing Michi-no-eki, which is good news. I hope that they will succeed in achieving local rejuvenation by building Michi-no-eki with significant potential in full consideration of visitor needs and expectations, their relationships with the area, and their mobility preferences. The three locations that we have chosen for the “community center” type under National Model Cases of Michi-no-eki are representative cases in point here. They were selected for the list in appreciation of their successful efforts to produce high value-added local charm, expand local employment, and serve as a hub for disaster prevention activities.

Michi-no-eki are installed by a municipal government and managed by a designated operator, which means that they must operate profitably. This is now a big headache for them to overcome.

Hashimoto: Is it like a joint venture company of local government and private capital?

Ishida: Some are like joint venture companies. Others are directly operated by municipal governments. There are some very unusual cases where people living in the region provide capital to form a corporation that manages the operations of a Michi-no-eki. In such a case, the local people are the shareholders of the company, so they do not pull out easily. This is a very good example of collaboration with local communities.

Hashimoto: The harder you work, the more you will be rewarded, right?

Ishida: Michi-no-eki must be managed profitably. That is the basic premise. Having said that, there is also high value placed on functions to improve local welfare, introduce folklore, and express local pride. It is true that some of these functions cannot be performed profitably. Many people currently seem to feel that they will make money out of Michi-no-eki, but this does not necessarily turn out to be the case. People need to take a more prudent approach here.

In the United States, national parks have visitor centers where it is possible to browse authentic local history exhibits as well as quality books written by local historians like those we have in our local communities in Japan. They are very educational. Aside from these exhibits, they offer a wide variety of guided tours, providing visitors with various options to enjoy themselves in the parks. They serve as local community hubs in a real sense! I hope that our Michi-no-eki will evolve to become like this in future, but this has not yet been addressed, as “operating profitably” appears to be a priority issue today. The Michi-no-eki station heads are struggling to make this happen, but they have not had any luck so far.

Michi-no-eki to create employment in regional areas

Hashimoto: I believe that the ones you have designated as model case stations are doing well in general. But I presume that some of the other facilities may be struggling to operate profitably.

Ishida: Quite a few facilities are not profitable, I’m afraid. An example of such unprofitable operations can be found in the regions, where municipal mergers and dissolutions, which are often referred to as the “Great Heisei Mergers,” have left redundant Michi-no-eki facilities within the same municipal district. Lingering legacy relationships among pre-merger municipalities make things even tougher i

n terms of integrating pre-merger facilities.

Hashimoto: Not all of the facilities always enjoy profitable management. This being the case, some municipal governments may run the risk of financing huge debts arising from the unprofitable operations of Michi-no-eki.

Ishida: It is not our policy to abandon the designations for those facilities that are operating unprofitably. Instead, we will make suggestions or recommendations to help the struggling municipalities operate their facilities profitably.

Michi-no-eki can contribute to creating jobs in the regional areas, which is their most attractive function. People living in the regions are already benefiting from the increased job opportunities created by Michi-no-eki, which helps them to feel confident in themselves. They also enjoy solid rewards in business areas including local tourism and the sixtiary industry, which involves processing and sales. This is a very important aspect, and we will provide assistance in these fields. In order to accelerate the pace of such developments, the government must hammer out effective measures and seek ideas from local communities. The government and the local community must help each other with complementary ideas.

Michi-no-eki can be found in as many as 1,040 locations all over Japan. Some are doing well and some are not. It is important to follow up on their performance and help the struggling operators to run better. Michi-no-eki were launched twenty-two years ago but, in a real sense, I believe that they have only just taken their initial step on the first rung of the ladder. I hope that Michi-no-eki will soon evolve to serve as local rejuvenation hubs.

Hashimoto: I hope that Michi-no-eki will grow successfully going forward. Thank you very much.

Special thanks to the All Nippon Michi-no-Eki Network.

Translated from “Tokubetsu Kikaku: Hanahiraku! ‘Michi-no-eki’ Shinjidai – Shinka shitsuzukeru chiiki-sosei no kyoten – (Special Feature: A new era of Michi-no-eki takes off! – Ever-evolving community hubs for local rejuvenation –),” Chuokoron, March 2015, pp. 234–239. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [March 2015]