Kagaku-Tsushin Island Signs: The Sign Language of Miyakubo in Ehime Prefecture

|

|

|

Yano Uiko |

Matsuoka Kazumi |

Yano Uiko, one of this article’s two authors, comes from Miyakubo Town, which is a part of Imabari City in Ehime Prefecture. The town is located on the island of Oshima, which is part of the Shimanami Kaido, a sea route connecting several Seto Inland Sea Islands. This area was notable during the Warring States period, and features the remains of a base that belonged to the Murakami Pirates. It has a thriving fishing industry, and there are many places where you can see rows of boats at their docks. Seafood is also a mainstay of the region’s economy and cuisine.

According to the 2010 national census some 2292 people lived in Miyakubo, and of those 18 were deaf. About 30 years ago more than 30 deaf people lived in the town, where Yano is from. All of her family are deaf: her parents and grandparents, and also her father’s siblings. It is not clear whether the relatively high number of deaf people in the town is related to genetics. In fact, the inhabitants of the town didn’t consider it particularly important whether people were deaf or not and thus never sought a reason.

At one point in time, both deaf people and hearing people in Miyakubo knew and used Miyakubo Sign Language in their home lives and while fishing. Since almost all the hearing people in the town could sign, both spoken Japanese and Miyakubo Sign Language were used in the area. If you went to the shore you would see both deaf and hearing people chatting in sign language, and residents were able to share information quite smoothly. When deaf friends of Yano came from Tokyo or Osaka to visit the island, they might write on a piece of paper, “Where is Yano’s house?” and show it to a passing hearing person. The hearing person would then reply in sign language: “I’ll show you. Follow me,” and lead them to her house. The hearing residents of Miyakubo were so expert at sign language that they could do this on a daily basis.

Japanese Sign Language (JSL) vs Signed Japanese

When people speak of “sign language” in Japan, they actually refer to several linguistically distinct languages, so the use of these terms needs to be clarified. What is referred to as ‘sign language’ can be divided into the following:

1) Japanese Sign Language. This is the native language of children born to deaf parents, and has grammatical features that differ from spoken Japanese.

2) Signed Japanese. This replaces Japanese words with signs borrowed from Japanese Sign Language, but follows the grammar of Japanese. It is also known as Manually Coded Japanese or Simultaneous Communication.

3) Mixed Sign. A mixture of the above two.

JSL is a language that developed naturally among deaf people in Japan and was passed down through the generations. As a language that developed based on the visual mode of meaning transfer, JSL has a set of distinctive grammatical features. On the other hand, Signed Japanese developed based on the auditory mode of meaning transfer, and is artificially made to correspond word by word to spoken Japanese. The grammar of signed Japanese is fundamentally different from JSL and any other sign languages. It is virtually a manually coded version of Japanese and cannot properly be regarded as a natural sign language.

The fact that sign languages of particular regions have linguistic features distinct from local spoken languages was first made clear in the research of primarily American linguists and psychologists in the 1960s. In Japan too, there is growing interest in research investigating the distinct features of JSL (as summarized in Saito 2016 (1) and Matsuoka 2015 (2)). However, people in Japan are not sufficiently aware of the plain fact that JSL is a separate language from Japanese.

Deaf people and those with hearing disabilities are a minority in Japanese society, but even among them native signers of JSL are a minority and are in an even more difficult position. First of all, as with anywhere in the world, the proportion of deaf children born to deaf parents is extremely low (around 10%, it is thought). Thus, the number of signers using sign language as their native language is extremely limited, even among deaf people.

What’s more, native signers of JSL struggle to have their voices heard in Japanese society. Native signers need to learn Japanese as a second language, which has many grammatical features that are different from JSL. Yet, with rare exceptions, deaf education in Japan doesn’t take into account the distinct differences between JSL and Japanese. For that reason, it has not been easy for native signers of JSL to acquire sufficient ability in Japanese. When people do not acquire sufficient ability in the dominant language of their community their opportunities to make their “voice” heard will be limited, and they will be forced into the position of a suppressed “minority within a minority”.

A language shared between deaf and hearing people: village sign languages and island sign languages

There are many regions and countries where it is recognized that multiple distinct languages are used. To date, there have also been a number of accounts from around the world (Perniss et al. 2007 (3), Zeshan and de Vos 2012 (4)) of relatively defined regions where not only are different spoken languages used, but there are also “village signs” (shared sign languages in the community) that function as a shared language for deaf and hearing people.

When village signs are used on an island they may be known as “island signs”. But when traffic with other regions becomes more frequent due to changes in the economic and political situation, the number of village sign users tends to rapidly decrease or disappear, and hence many village sign languages reach the verge of extinction.

It has been reported that there are regional varieties (dialects) of JSL in various parts of Japan, just like regional dialects of spoken Japanese. Unlike many dialects of JSL, Miyakubo Sign Language shows major variations beyond differing sets of vocabulary items. It can be considered an island sign language due to its grammatical features distinct from JSL. Below, we will give an example of the unique grammatical features of Miyakubo Sign Language.

The special linguistic features of Miyakubo sign language

We have been researching Miyakubo’s sign language since 2014. Like other village sign languages reported outside Japan, Miyakubo Sign language can be considered as being at an intermediary stage of development between gesture and language.

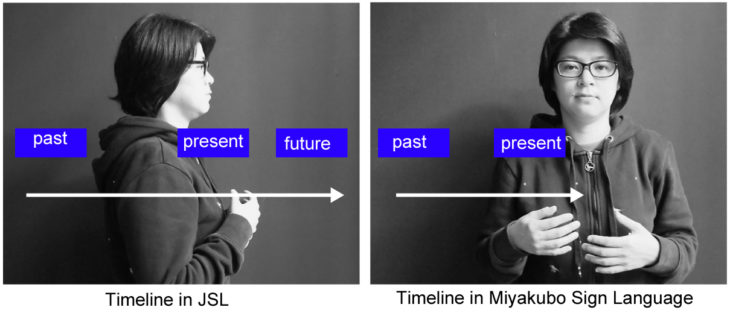

As mentioned earlier, the differences between JSL and Miyakubo Sign Language are not just those of signed words. An example is given in the illustration below, which shows a spatial representation of time known as a “timeline”. JSL uses a timeline (see the illustration on the left) which represents the time from the back of the signer’s shoulder to the space in front of the signer: i.e. past behind the body, present at the body, and future in front of the body. The timeline for Miyakubo sign language, on the other hand, (see the illustration on the right) shows the flow of the time horizontally from the dominant side to center.

It is of particular interest that the flow of time expressed in Miyakubo Sign Language timeline covers the past to the present. The future is expressed without any particular spatial position. Various forms of timelines are often discussed as examples to show the diversity of sign languages in the world. It is notable that the diversity of the timelines can be found within different regions of the same country.

Expressions for the flow of time in JSL and in Miyakubo Sign Language

Miyakubo Sign Language today

Yano, like many other deaf children in Japan, left the island and entered a school for the deaf in Matsuyama City. Back then, she mistakenly thought that all the people in the world used a sign language. For that reason, when she moved into the dorm, the fact that she couldn’t freely use sign language was more of a shock than being separated from her parents.

When her grandmother came to meet her at the dormitory each week to take her home for weekend visits, the deaf and hearing staff who learned Signed Japanese criticized her grandma’s signing as being “strange”. Grandma was so hurt that she wouldn’t talk for some time, and the whole family was furious. Outside the island, other deaf people looked down on the sign language cherished by people in Miyakubo.

Even though Yano wanted to stress how Miyakubo Sign Language was an important language, spoken Japanese was considered far more important than sign language at schools for the deaf. Educators were convinced that sign language wouldn’t be useful when students left the school, and unfortunately that policy has barely changed in deaf education today. Opportunities for deaf children to interact with each other in their own sign language have not been sufficiently provided in educational institutions. When Yano wonders how long the deaf will have to struggle to recover their own language, she feels overwhelmed by the unreasonableness of the situation.

Though Yano was not happy with the situation at school, she was still able to communicate in Miyakubo Sign Language with islanders whenever she returned to the island until 10 years ago. Around the year 2000, however, a bridge was completed that connected Ehime-Oshima Island to th1e rest of the Imabari City and other islands, and it became easier to travel to and from other areas. On top of that, there were other major changes in the social environment, such as the spread of the Internet. Instead of asking questions to hearing neighbors using sign language, younger deaf people in Miyakubo began to search for information by themselves. With fewer opportunities to meet face-to-face and communicate using sign language, young hearing people on the island have less chance to use Miyakubo Sign Language.

The deaf people of Miyakubo are becoming more isolated. The paternal aunt of Yano, 73 years old, laments the situation, saying:

“Before, we could talk and understand freely so we were able to share all the pleasures and pains of life. These days, no one knows the sign language. There are many sign words new to me, so I don’t even know what other deaf people are saying. I want people to continue to use and treasure Miyakubo Sign Language.”

As deaf Miyakubo residents age, Miyakubo Sign Language faces extinction. As one of the inheritors of the sign language, Yano feels strongly that Miyakubo Sign language must be properly recorded and preserved to prevent it from disappearing without a trace.

Translated from “Kagaku Tsushin, Ehime-ken Oshimamiyakubo-cho no shuwa: airando sain (Kagaku-Tsushin, Island Signs: The Sign Language of Miyakubo in Ehime Prefecture” Kagaku, May 2017, pp. 0415-0417, ©2017 by Yano Uiko and Matsuoka Kazumi. Reprinted by permission of the authors c/o Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. [May 2017]