Ultra-aging Japan’s “issue of the 24th year of Reiwa” ― Department stores and banks will close down and local governments will reduce by half

The year 2042 will be Japan’s greatest crisis. […] According to projections released by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS), the number of elderly people will reach about 39,352,000, the most ever.

Photo: Luce / PIXTA

Kawai Masashi, writer and journalist

A new emperor has ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne, marking the beginning of the Reiwa era. The whole of Japan is caught up in the celebratory mood. However, given the situation in which Japanese society currently finds itself, we cannot afford to be in high spirits.

In April 2019, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications released population projections as of October 1, 2018. The total population decreased by about 263,000 from the previous year to 126,443,000, a decline for the eighth year in a row. The total population includes foreigners. Because the number of foreigners increased by about 165,000, the Japanese population alone decreased by as many as 430,000. Both the decrease in the population and the rate of decline were the largest ever since the comparable year of 1950.

In addition, the population of people aged 70 or older exceeded 20% in comparison with the total population, while the population of people aged 14 and younger recorded the smallest ever number. This shows that the declining birthrate and population aging are increasingly underway.

Heisei was an era in which people just sat back and watched the decrease in the number of births. In the first year of Heisei (1989), the total fertility rate (TFR), which is the total number of children born to a woman in her lifetime, was 1.57, which was below the rate of 1.58 in the year of hinoe uma (1966), the lowest before that. Of course, the media gave this fact a lot of coverage, but the Japanese people who were living it up during the bubble economy at the time did not listen closely to the reports.

Subsequently, the TFR continued to fall, but the government did not tackle the issue seriously. As Heisei neared its end, the government rushed to attempt to get into full gear for measures to address the declining birthrate. The government was unable to achieve immediate results, however.

Because many people have chosen to remain single or not to have children after marriage, Japan has become a depopulation society. The population increased consistently after World War II, but it entered a decreasing phase following the peak in 2008.

Unfortunately, the Reiwa era falls in the period when Japan’s declining birthrate, population aging and population decline will accelerate more than ever before.

For some time now, I have insisted that the year 2042 will be Japan’s greatest crisis. This is because the first baby boomers who were born in 1947 to 1949 and the second baby boomers who were born in 1971 to 1974 will be 65 or older by then. According to projections released by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS), the number of elderly people will reach about 39,352,000, the most ever.

Although the absolute number of elderly people is increasing, the facilities and staff that accept them are in short supply. In addition, the second baby boomers are also the generation who underwent the employment ice age. Non-regular employees began to increase in number, and there are quite a few cases where even full-time employees face unstable wages because the management situation of their companies is tight. People’s savings for retired life are not sufficient, and the number of elderly people who only receive a low pension or do not receive any pension at all during their retirement will increase sharply. On the other hand, the number of young people is decreasing, and this structure will surface in 2042.

Subsequently, the population decrease will accelerate immediately, just like rolling down a steep downhill slope. According to Population Projections for Japan (2016–2065) compiled by IPSS, Japan’s population will decrease to about 88,000,000 in 2065 and to about 50,600,000 in 2117.

In addition, according to the same projections released by IPSS, in 2067 the population of people aged 100 or older will be 565,000, relative to the annual number of births of 546,000. That is, the population of elderly people aged 100 or older will outnumber the babies born.

Such a rapid population decrease and the acceleration of the declining birthrate and population aging are unprecedented in world history. Japan is now stepping into that crisis situation.

The collapse of an excessive-service society

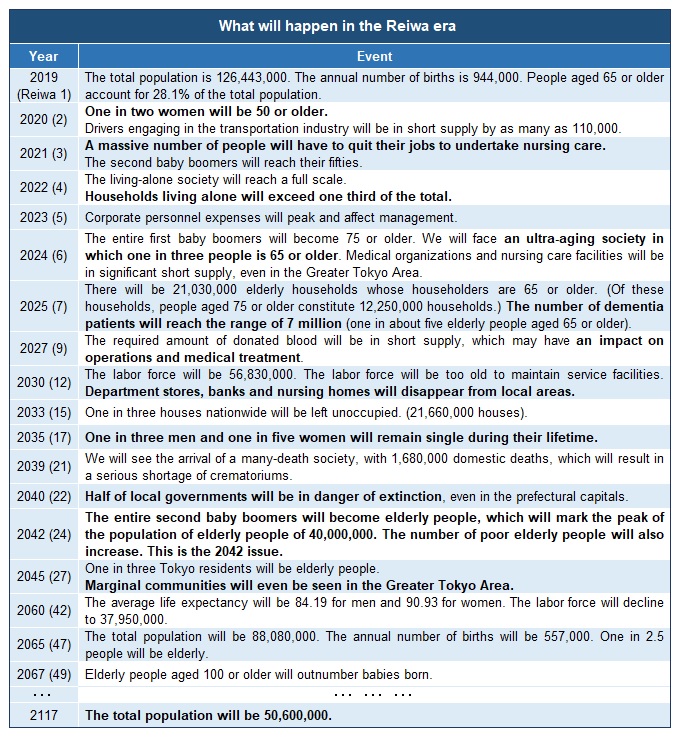

If the government takes no measures and the population continues to decrease as it is now, what will happen to Japanese society in the Reiwa era?

The first thing that will happen is the shortage of workers. This will surface in many areas. According to a national census, the labor force (age 15 and over) was about 60,750,000 in 2015. On the other hand, according to projections calculated tentatively by the Cabinet Office in 2014, supposing that every working environment develops as it is, the labor force is predicted to shrink to about 56,830,000 in 2030 and to about 37,950,000 in 2060.

The labor force will be getting older. In 2015, people aged 50 to 64 numbered around 17,630,000 in the labor force. A simple calculation shows that people aged 50 to 64 account for one third of the labor force at present. According to projections by IPSS, people aged 50 or older will account for more than 40% in 2040.

An overwhelming shortage of service suppliers has already become a social issue. In 2020, truck drivers will be in short supply to the tune of 106,000. (Current Status and Issues for Work Style Reforms in the Motor Truck Transportation Business compiled by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism). Various media have reported on the shortage of home parcel delivery service drivers, which makes delivery sites disastrous.

Behind this is the fact that Japan is becoming an excessive-service society. This tendency became rapidly evident around the end of the Showa period (1926–1989). The manufacturing industry lost the strength that it used to have, and factories were relocated overseas. New receptacles for employment were needed, and the service industry replaced heavy industries and developed rapidly. I guess that the fact that the custom according to which you should pay money to someone and ask him to do work that you find troublesome became common during the bubble economy in the Heisei period was also another factor.

There is currently a lot of talk about whether or not convenience stores that represent the Japanese service industry will continue their around-the-clock operations. This began with stores screaming out for help because they failed to recruit shop assistants to maintain their around-the-clock operations. In response to this request for help, the headquarters first replied that they would bring their staff to support the stores and that they hoped that the stores would continue to operate 24 hours. This answer digresses from the essence of the problem, however.

This is because as well as shop assistants, other things will also be in short supply from now on. People who make box lunches and ready-prepared food and drivers who carry products by truck will also be in short supply. Convenience stores did not have storehouses and worked according to the business model of thoroughly managing when products will be carried in and how many products will be carried in. Depending on the region, however, this business model may not work from now on.

According to Regional Economy 2016, a report compiled by the Cabinet Office, it is predicted that in 38 prefectures, which is 80% of the total, supply capabilities within the regions will be unable to meet demand in fiscal 2030 due to insufficient production capabilities. This would make it impossible to maintain services that are indispensable for residents’ lives. Department stores, banks, hospitals and nursing homes would also be able to maintain stores only in areas where they can expect to secure a certain number of customers and would be unable to survive in many local regions.

The shortage of manpower is not limited to private companies. According to policy recommendations drawn up by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ Study Group on Local Government Strategy 2040 Vision, public administration will need to be supported by half of the current number of officials by 2040. Many of the officials of village and town offices are from those areas. That is, if the local population continues to decrease, the number of public officials who provide local government services will also have to be reduced. Although local residents will get older and will need more help than they do now, the number of public officials will reduce.

In addition, it is also becoming more and more difficult to secure human resources for work that requires a young labor force, such as police officers, fire fighters and Self-Defense Force officials. Japan’s safety and security myth, which people have taken for granted to date, is about to collapse.

Unemployment for nursing care that is projected to increase further will accelerate the labor shortage. Generally speaking, around the time when people reach the age of 50, their parents are old enough to be certified by the municipal government as being in need of nursing care. More and more people, even those in their forties, are now having to care for their parents.

Currently, the number of people who have to quit their jobs each year to undertake nursing care is stable at about as many as 100,000. This is because the government cut down on services by making the standards for entering care homes for the elderly more rigorous or raising the individual share of expenses to avoid the collapse of nursing care insurance finances. As a result of the government’s nursing care policy shift from facilities to homes, nursing care refugees were produced on a large scale, and people had to quit their jobs one after another.

Accordingly, it is thought that unemployment for nursing care will enter the limelight as early as 2021, when the first group of the second baby boomers will reach their fifties.

An increasing number of people will take a day off in the morning or leave the office early to help their parents to receive outpatient treatment, if they do not quit their jobs. The shortage of workers will spread more than the government supposes it will. The current services will be unable to be maintained in most areas.

Consumers’ changing needs

Another thing that will occur in addition to the manpower shortage is the major transformation of society due to the aging population. Japan has succeeded in achieving longevity and has already become an ultra-aging society in which the population of people aged 65 or older is more than 28%.

In 2020, one in two women will be 50 years old or older. Four years later, the entire first baby boomers will be 75 years old or older; one in three Japanese will be 65 years old or older and one in six Japanese will be 75 years old or older. Japan will be an ultra-aging society in which the annual number of deaths will surpass 1.5 million, double the number of births.

Population aging will accelerate rapidly in greater metropolitan areas, including the Greater Tokyo Area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba), as well as local areas. There is concern that medical organizations and nursing care facilities will be unable to keep up with the dramatic increase in the number of acute patients and elderly people in need of nursing care. In addition, it is considered that many issues, such as the increase in the number of dementia patients, the swelling of social security expenditure and how to secure local public transit systems and housing for elderly people, will surface nationwide in 2024.

Conventional ways of thinking will not work for an ultra-aging society. For example, consumers’ needs will change dramatically in terms of business.

It is not simply about products for elderly people selling well and products for young people not selling well. Companies must even consider producing goods that can be used easily by elderly people when they arrive. In the case of beverages, for example, when providing products, companies need to go as far as to think about whether elderly people can open milk packages and whether they can hold a 2-liter pet bottle in their hand and pour it into a cup.

Disappointingly, it is true that many people are still unable to think that way. Because they suppose that the current society will continue as it is, they cannot understand what an aging society will be like.

If I introduce an extreme example, there is a possibility that no matter how much money people have, it will make no sense in Japan in the future. For example, people called house-moving refugees who cannot make a reservation to move to another place have appeared. Even if they say that they will pay double the fee, they cannot move due to the manpower shortage. There have been cases where a dealer has leveled an outrageous price at elderly people and declined their requests aggressively. Such things can occur in every field from now on.

If we face a society in which we have difficulty gaining access to the products and services we want, no matter how much money we have, we will be unable to acquire them even if we pay millions of yen. This is a “society in which money goes rotten,” even if you save tens of millions of yen. A depopulation society is synonymous with the end of a “society in which you can manage only if you have money.”

If you find it difficult to imagine such a society, I suggest that you add 20 or 30 years to your age and imagine that such people are everywhere around you, which will make you realize that many things are quite different from how they are in the current society.

If things are left as they are, Japan will see its population continue to decrease in the future, and it will be unable to handle measures for elderly people properly. Double domestic administration issues will continue to bear down hard on Japan. No matter how many financial resources Japan has, it is clear that the country will reach bankruptcy.

The Abe administration has implemented several measures, but the fact is that they do not work as fundamental solutions.

For example, the Abe administration announced that it would increase the acceptance of foreign workers. Prime Minister Abe, who had declared that he would not adopt an immigration policy, shifted his policy to the full-scale acceptance of foreign workers for the first time. He revised the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act and established a new residence status called “specified skilled worker.” The administration plans to accept a maximum of about 345,000 foreigners as workers, not as trainees, in five years.

Of course, the labor shortage can be compensated for temporarily and partially. But even if production and service provision systems can be maintained with temporary assistance for some time, the market will shrink significantly due to depopulation. Amid population aging, public preferences will change significantly, and per capita consumption will also reduce. The imbalance between supply and demand cannot be controlled.

This is also the case with artificial intelligence development. Reportedly, an AI-related budget totaled around 120 billion yen in the draft budget for fiscal 2019, up 1.5-fold from the previous fiscal year, exceeding 100 billion yen in the initial budget for the first time. Of course, it is wonderful that the government places emphasis on innovation. There is a possibility that some innovation will be produced, and I have expectations for such a future. But these government efforts cannot be fundamentally decisive in terms of depopulation measures.

I predict that human work will be partially replaced by AI in some fields. But this is just a story about facilitating greater operational efficiency. I do not think that AI development will go as far as to resolve the shortage of labor caused by the increase in the number of elderly people. AI researchers aim to achieve greater operational efficiency, but they do not work on technical development with a focus on a grand design for depopulation measures.

In addition, technical possibility is one thing, but it is another thing to put AI into practical use at low cost and promote its use nationwide. It is almost impossible to advance technical development to the level of being able to resolve the manpower shortage nationwide in 10 to 20 years.

In the first place, the biggest question is that the Abe administration’s approach to the population issue starts with maintaining the status quo.

In 2014, the Abe administration approved the goal of “maintaining a population of about 100 million in 50 years with a stable demographic structure” at a Cabinet meeting. I can understand the administration’s setting a numerical target, but the number of 100 million is unrealistic. This number probably includes foreign immigrants. But according to Population Projections for Japan (2016–2065) compiled by IPSS, the Japanese population will drop to 88.08 million by 2065. As a result, even if the birthrate improves significantly, the numeral target will not be able to be achieved unless Japan accepts a considerable number of immigrants.

If the Japanese government tries to achieve this numerical target of 100 million, it will end up just thinking about measures for compensating for it. It cannot be a fundamental solution.

Currently, the government is expected to abandon this vision of maintaining the status quo and to advance policies based on the premise that depopulation and a transformation to an ultra-aging society will be unavoidable.

Aim to build a hub-based nation

What specific action should the government take? I think that it is necessary to accept a depopulation society and “shrink strategically” to rebuild social structures. In this context, shrinking means neither a decline nor a defeat. Shrinking enables Japan to protect itself and become richer than it was before.

I will explain this by using local governments as an example. As a result of the great Heisei municipal merger implemented by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, local governments were combined into an aggregate of small-scale local governments. Their areas increased, but the number of officials declined, and the local residents became older and more interspersed. As a result, according to future projections released by the Japan Policy Council’s Subcommittee for Deliberating on the Depopulation Issue consisting of private experts in 2014, it is said that half of the local governments nationwide will be in danger of extinction by 2040. Some local governments will even face a population of less than 100 and an aging rate of almost 80%.

In the nationwide local elections in April 2019, the candidates won without voting, and the number of candidates did not reach the full number in some local governments. This is largely because more and more people have difficulty working as assembly members due to old age amid the accelerated population aging. The autonomy of local governments itself is in jeopardy.

I want to propose the concept of a hub-based nation before many local governments cannot provide administrative services to too many elderly people due to the depopulation.

A hub-based nation is a society in which a bustling town in a depopulated area is selected as a hub and people concentrate and live in the town. The concentration of local residents in the town enables every single resident to fully enjoy the services. The local residents can enjoy efficient medical, administrative, postal and parcel delivery services by just moving to town blocks in each area. This will enable suppliers to reduce operational costs and local residents to curb unnecessary expenses.

By main service, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism calculated the scale of demand necessary for location with a focus on the conditions under which particular types of business can work in particular areas with a certain number of residents (Grand Design of National Spatial Development towards 2050, released in 2014). According to this calculation, retail stores dealing with food, post offices and general clinics can work with a population of at least 500. That is why hubs need to have at least 500 residents. Of course, you can have hubs with 1,000 to 5,000 residents.

Successful examples of hub-based nations can be found in Italy and Switzerland. In both countries, villages with populations of 500 have jobs that provide benefits to 500 people. What is important is that they do not seek difficult expansion. Those villages sell unique quality products that only they can make. These products become brands, which buyers from around the world come to the villages to buy, which enables the people in the areas to achieve sufficient earnings to make a living.

Up until today, if Japan discovered a lucrative business, it expanded the factories by making plant and equipment investments and increased employment in an effort to expand the business scale as much as possible. But villages making brand products in Italy and Switzerland are not like that. These villages place emphasis on technical innovation, but they do not seek difficult expansion. It is necessary to break away from the concept of working and expanding furiously.

To maintain its wealth and affluence, Japan must shift to the business model of selling each product at a high price by creating added value, even through small-quantity production. Great traditional industries also exist in many parts of Japan. Towns with such industries are often prosperous in the surrounding areas and can be sufficient hubs. If you add new ideas and technologies to those towns and improve them, they will be reborn as hubs that are sufficiently attractive to draw global attention.

For some areas, the method of constructing smart cities, the core of a hub-based nation, is conceivable. But Japan today has no time to spare to construct such smart cities on vacant lots from scratch. First, you designate a certain lot of an urban district in a local city as a special zone. You then reproduce the special zone as a high-tech area, bringing together Japanese science and technology into a town where everyone wants to live. The utilization of advanced technology will enable even elderly people to live on their own.

This is an example of shrinking strategically. I believe that Japan will be able to maintain its wealth and affluence by making companies and families as well as local governments small and compact.

What Japan should do in the Reiwa era

The fact that the decline in the number of births cannot be stemmed does not mean that Japan has no need to take any measures regarding its declining birthrate. If Japan finds anyone who wishes for marriage and children but is unable to achieve these things, the country should support that person. If Japan can get the declining birthrate to slow down, even just a little, it will result in the achievement of more time to rebuild society.

One of the reasons why the government has neglected measures for addressing the declining birthrate to date is that those measures remind people of the policy of giving birth to more children and improving wealth before and during World War II. That is why the Abe administration has placed emphasis on measures for supporting child-rearing, not for addressing the declining birthrate. This is rather ineffective, however.

Many other countries take even better care in economically supporting couples who have many children to raise as measures for addressing the declining birthrate, and Japan should adopt this policy. The main reason why couples decide not to have third children is economic strength. I think that the government should award grants of around 10 million yen in cash to households with three or more children. I believe that the government should take such a bold measure before the number of women of childbearing age decreases sharply.

There is a limit to what the private sector can do to urge social transformation. The government must take the initiative in leading them in the right direction.

Now that we have entered the Reiwa era, if we make a wrong choice from among the imaginable policy options, this country is certain to decline. A new emperor has ascended to the Chrysanthemum Throne at the age of 59. We will face the 2042 issue, which I think will probably be Japan’s largest crisis, during the Reiwa era.

Ahead of this, we will enter a full-blown depopulation age when the population will decline by 900,000 every year. We must change Japanese society during the Reiwa era. There is only a little time left for us.

Translated from “Reiwa no mirai nenpyo: Cho-koreikashakai no ‘Reiwa 24 nen mondai’ ―Hyakkaten ya ginko ga heitenshi jichitai wa hangensuru (The future chronology of Reiwa: Ultra-aging Japan’s “issue of the 24th year of Reiwa”―Department stores and banks will close down and local governments will reduce by half),” Bungeishunju, June 2019, pp. 270–279. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [July 2019]

Keywords

- Kawai Masashi

- Masashi Kawai

- Reiwa

- total fertility rate

- declining birthrate

- first baby boomers

- second baby boomers

- employment ice age

- non-regular employees

- labor force

- labor shortage

- bubble economy

- Heisei

- Showa

- ultra-aging society

- depopulation society

- excessive-service society

- Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act

- specified skilled worker