Labor Unions Today: The Challenge of Addressing Division Among “Non-regular Workers”

The “voice” function of labor unions in negotiations is said to be important. The unionization ratio of labor unions, which once boasted of their power, has been continuously declining.

Photo: fukagawa@222 / PIXTA

Key points

- The “voice” function of labor unions in negotiations is important

- The cost of organization is increasing with the shift to a service economy

- Increasing the organization of non-regular workers to approach that of regular employees

Umezaki Osamu, Professor, Hosei University

Among the economic entities in Japan today, labor unions are markedly hard to understand. Historically, labor unions boasted a high unionization ratio and had clear goals, such as raising wages in the spring labor offensive (shunto) and eliminating status differences for workers and employees. Moreover, Japanese society accepted that they had the power to do so.

There are few labor issues nowadays, so the presence of labor unions seems to be diminishing. However, with stagnant wage increases and the emergence of new labor problems, labor unions are arguably as important as ever.

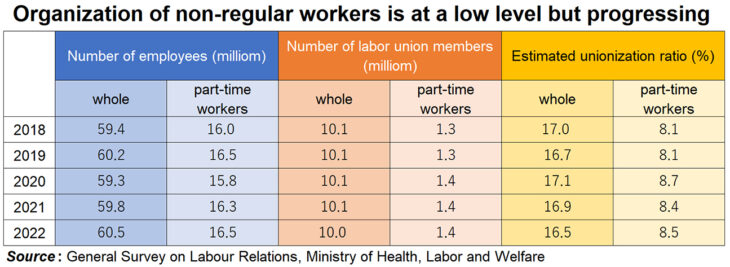

The environment surrounding labor unions is harsh. The unionization ratio has consistently trended downward, reaching a record low of 16.5% in 2022 (see table).

Moreover, when I analyzed the “Questionnaire on Work and Life of Workers” from the JTUC [Japanese Trade Union Confederation] Research Institute for Advancement of Living Standards (RENGO-RIALS), I found that the number of respondents answering “I don’t know if there are labor unions” has risen from 10% to 22% in about 20 years. Labor unions have also become objects of indifference.

Naturally, expectations are also declining. When asked about the impact of labor unions on companies and workers, the number of respondents answering “they have no impact on companies” has risen from 2% to 36%, while those answering “they have no impact on workers” has risen sharply, from 11% to 36%. Now there is even a sense that unions are powerless. These results are causing a dissonance with the actual functions of labor unions. The functions of labor unions can be explained theoretically, and it has not been shown that they are powerless. It is widely known that there are limits to how wages are determined by market mechanisms. Wages are determined based on companies’ assessment and benefits systems, but negotiations between labor and management are key to what kind of systems are designed. Various personnel systems are also involved in how the work is done, so it is necessary to negotiate these one by one. Moreover, there is a limit to how much one person can understand the complexity of a personnel system and influence its design. It is better to train leaders familiar with the systems in organizations called labor unions as well as to create arrangements for the negotiations. There is also the issue of incomplete employment contracts. A worker cannot promise all the details of the labor services for which they will be compensated at the time of concluding the contract. It might be possible if routine work makes up the bulk of the work, but it is difficult to determine work objectives in advance for highly non-routine work that requires flexible responses.

During negotiations, it is stipulated that the function of the labor union is to exercise the power of “voice.” Many empirical studies have been conducted on the “voice-exit” model according to which workers choose to resign (quit their jobs) if they lack the power of speech. Many studies have confirmed that the power of speech affects working conditions, productivity, and retention. Labor unions have been confirmed to be effective in theory as well as empirical research, so why does the unionization ratio continue to decline not only in Japan but also in Western countries? One reason identified is that common social changes in these countries are driving up the costs of organizing, with the costs of organizing increasing faster than the benefits of labor unions. In the past, when manufacturing was the main industry, most workers gathered to work in the same place and at the same time. In-house unions in Japan were likewise basically formed with places of business as their bases. Interacting with people in the same workplace and empathizing with each other made up the basis of the union movement. As business activities became more complex and reached the current state, it became more difficult for workers, except in some industries, to feel a commonality in terms of career at a level of “occupation.” In other words, people in different workplaces and employment categories are now working at different times and in different places. As such, the “cost of solidarity” cannot but be high. The unionization ratio of part-time workers, who often work in different places and at different times, is 8.5%, which is much lower than the overall ratio (see table). Interpreting costs in this way allows us to understand the seriousness of workers. Having ended up alone, you have no choice but to negotiate alone.

Meanwhile, the unionization ratio of part-time workers has barely changed in recent years, which contrasts with the overall downward trend. This is because of the existence of labor unions that yield results with regard to organization. The UA Zensen (the Japanese Federation of Textile, Chemical, Food, Commercial, Service and General Workers’ Unions known as UA Zensen) is the biggest industrial organization in the Japan Trade Union Confederation (Rengo).

UA Zensen, which has seen a remarkable increase in union membership, was originally an industrial organization consisting mainly of workers in the textile industry (manufacturing). As it expanded, it succeeded in organizing workers in service industries, such as distribution, food, and beverage, as well. As such, UA Zensen is not an “industrial union” but a multi-industrial union.

As mentioned above, the shift to a service economy and an increase in non-regular workers leads to a decrease in the unionization ratio. However, while UA Zensen targets the distribution and service industries, about 70% of the unions have 299 or fewer members, about 60% of whom are part-time workers.

The organization of non-regular workers and others in the distribution industry, as represented by UA Zensen, may be termed an achievement of the Japanese union movement. At the same time, however, it also renders labor unions as a whole “difficult to understand.”

Not only are there numerous part-time workers in the distribution industry, but there are also many long-term employees who have become “qualitatively critical” and do work that used to be performed by full-time employees. An easy way to look at this is imagining an increase in part-time workers more familiar with the sales floor than full-time store managers who repeatedly and regularly undergo transfers.

In other words, the success of UA Zensen’s organization is partly due to its organizational structure and know-how, but also because it targets qualitatively critical non-regular workers. When it comes to organization, we often talk about the gap between regular and non-regular workers, but a close examination of the facts shows that organization really starts with non-regular workers who are close to regular employees. UA Zensen’s organization takes on a gradualist character that goes beyond the regular/non-regular worker divide.

At the same time, it creates a hidden divide among non-regular workers, between qualitatively skilled and unskilled workers. Their shared attribute of being skilled makes apparent a gap between them and their unskilled peers. One statement that was once advocated by Marx and that is still repeated in other forms is that “de-skilling of the labor forces comes with technological progress.” Many have argued that a labor union organization that emphasizes a common attribute of being skilled is an anti-historical movement with regard to creating an unskilled working class. This prediction has been proven wrong as history has shown that de-skilling was followed by new skilling.

Still, the problem now is that even though skills are a common element for creating associates in the form of a labor union, whether or not you have certain skills constitutes a barrier to participation. The message of “gradual organization” to qualitatively crucial workers deviates from the message to the labor force as a whole, including unskilled workers.

Labor movements need to overcome the difficult challenge of sending a variety of messages to a variety of positions. For example, UA Zensen has been conducting surveys and issuing information on how to deal with “customer harassment,” which is significant nuisance caused by customers, and has been urging the government to develop countermeasures. Customer harassment measures are an issue that affect unskilled workers in the distribution and service industries, so this may be seen as an attempt at a movement that encompasses diverse positions.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 15 December 2023 under the title, “Rodokumiai no ima (II): “Hi-seiki” nai bundan eno taio kadai (Labor Unions Today: The Challenge of Addressing Division Among ‘Non-regular Workers’),” The Nikkei, 15 December 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Umezaki Osamu

- Hosei University

- labor unions

- labor movements

- unionization

- non-regular workers

- regular employees

- division

- “voice” function

- negotiations

- organization

- labor

- management

- personnel

- service economy

- wages

- shunto

- spring labor offensive

- commonality

- solidarity

- UA Zensen

- Rengo

- customer harrassment