Calling Us Minzoku, an Ethnic Group

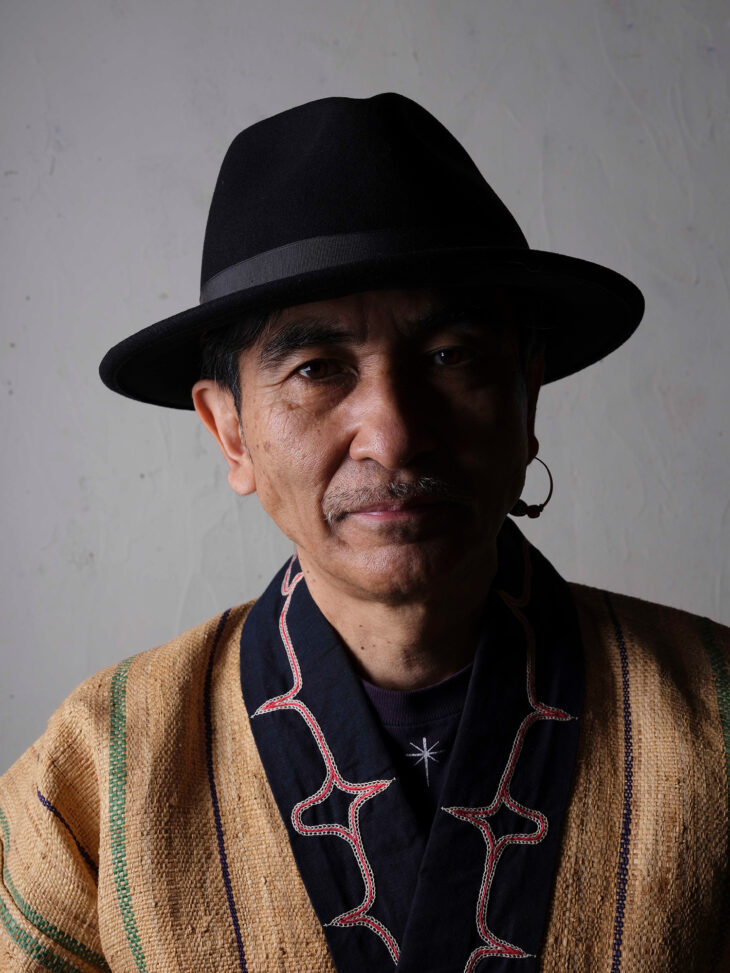

OKI, musician

Irankarapte. The low voice of the conductor echoes through the quiet train. The Ainu greeting is used casually to make people feel more familiar with Ainu culture, in the same way that saying “nihao” might be in China, but when this announcement is made, I unintentionally become defensive. I feel like I want to erase my presence. My home is the next town over from Asahikawa (in north central Hokkaido). It is mainly an agricultural town, but many newcomers have moved to the town, too. A young man whose father is Niikappu Ainu (in Hidaka, southern Hokkaido) and whose mother is Filipino recently moved in. This gives the town two Ainu households. Just as I moved here because I liked the town, this is not a place that was home to an Ainu village in the past. Compared to places with concentrated Ainu populations like Akan (eastern Hokkaido) and Shiraoi (central and southern Hokkaido), the environment here is different. My neighbors know that I am Ainu and a musician, but I am living a normal life, having blended in to my surroundings. Positions within the neighborhood association rotate, and currently I am in charge of the shrine committee.

We are in the midst of an ongoing Ainu boom now, perhaps due to the impact of media attention to the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park which opened two years ago (in 2020). There are Ainu articles in regional Hokkaido newspapers every day, so everyone knows about Upopoy. The museum even came up in conversation with the farmer next door. Even while Upopoy has been criticized from all directions, I sense that Ainu status within Hokkaido has been elevated a little now that a national museum has been built. It feels like something hidden in plain sight has now been exposed by the light.

When I turn on the TV, there is news of multiple movies in production which feature Ainu themes. None of these movies seem to star Ainu people in the leading roles. While some are calling for more Ainu people to be cast in these films, at the same time, other people are scared to appear in a film where the viewers have no interest in whether Ainu people are in the cast or not, while others take a wait-and-see approach. This is kind of frustrating. From my perspective, the real problem is that Ainu people are unable to compose their own script or direct a film on their own. If I were a director, I’d make a movie about an Ainu bank robbery. Thirty Shamo (Ainu language term for ethnic Japanese, shortened from original “Shisamu”) and 30 Ainu would die in the film. There would be no shortage of actors.

Recently, my wife went to the clinic for intense lower back pain. She reported that the doctor appeared to be a kind older man, but he has another face – he is a highly vocal Ainu denier. He has published three books with the following titles: “The Ainu Indigenous People, an Inconvenient Truth,” “The National Ainu Museum is an Interest Group mired in Lies and Fabrications with Close Ties to Anti-Japanese Forces” and “Ainu Organizations, their North Korean Backers, and their Plans to take control over Local Governments.” I am concerned that this doctor, whose dislike for Ainu in these books is so intense, would change his treatment of my wife if he knew that she was Ainu.

The Hokkaido Utari Association, which was the predecessor to the Ainu Association of Hokkaido, began holding the Ainu Culture Festival in 1989. The program for this festival consisted of a keynote speech by a wajin (ethnic Japanese) scholar on “this is what Ainu culture is,” followed by traditional dances, songs, and Ainu language plays, as if to say “and this is what the Ainu people are like today.” While it was a rather colonial program, it didn’t bother us and we enjoyed the festival and the after-party. The venue was in a different district each year, so we were able to meet with Ainu people that we don’t normally see.

These days we hear the term “Ainu” quite frequently, but until just a few decades ago, we called ourselves “utari” (friends or comrades). For me this word sounds like a mixture of joy, sadness, love, and hate, all together. It feels like something that cannot be wrapped neatly under the term “ethnic group.”

After Ainu were recognized as Indigenous peoples in 2008, the Utari Association changed its name to the Ainu Association as they had decided to proudly identify as Ainu from then on. Responsibility for the Ainu Festival was then shifted to the Foundation for Ainu Culture whose main agenda is to spread appreciation of Ainu culture. Nowadays the festival is held in relatively large venues across Japan several times a year. It has transformed into an educational event for ordinary citizens, maintaining the same structure as the Ainu Culture Festival of the past featuring a wajin-authored keynote speech and dances by the traditional dance groups. While times may have changed, the festival’s role as a place for socializing among Ainu people is over. Spreading culture and deepening culture are two different things.

I was struck by this realization when we held the first Ainu Music Festival in Mitsuishi, Hidaka district, a town rimmed by the Pacific Ocean. Mitsuishi, with the Hidaka Mountains in the background, is famous for producing kelp. It also has an interesting history. In the 17th century, a conflict between Shakushain and Onibishi, who was allied with the Tokugawa shogunate and in control of the western side of the river, escalated into a war involving the Matsumae clan as well. Shakushain’s fortress was on the eastern banks of the Shizunai River. Mitsuishi, on the eastern flank of Shizunai, allied itself with Shakushain.

At the urging of Mitsuishi Ainu Association’s director, “we should hold an Ainu Music Festival!” six individual artists and groups were chosen to participate. This was a new approach: there were no performances of traditional Ainu dance or music by preservation societies. There were no keynote speeches by a researcher. I was put in charge of stage production. On October 23, 2022, the hall was so packed that the audience could not be seated even at showtime. Hidaka has a large Ainu population, so many Ainu people came to the hall. Ainu language teachers also came. Actually, it takes some nerves to sing or perform in front of fellow Ainu and language teachers. The Ainu of the past were so accomplished that many Ainu of today feel that we cannot surpass what our ancestors created. Am I doing this all right? Did I get the Ainu language right? As each of us approached the stage we tried to shrug off this immense pressure. Even so, once the songs began, singers were encouraged by the cheers and applause of their aunties who rushed the stage to applaud them, and later they realized they had been worrying too much.

During the singing contest finale, everyone blended their own local Ainu songs with the rhythm of the tonkori, a Sakhalin Ainu stringed instrument. Each artist had a distinct personality and each displayed particular forms of vocal expression, and yet we share a common foundation as Ainu. We reaffirmed this foundation by weaving our voices together and communicated that with the audience, as well. In recent years, the Ainu have been pulled into all sorts of promotional campaigns, yet I think it would be good to reconsider who Ainu culture belongs to once again. It seems like we have forgotten how to enjoy ourselves on our own terms. The 2022 Ainu Music Festival was the first “By Utari and For Utari” festival in a long time.

After the performance, a reporter asked me how many songs had been performed, but this was an irrelevant question that would not appear in the article anyway. Without answering the question, I jokingly replied, “The music of the Ainu people: Rocking the Soul,” that’s what the title will be, won’t it?” The title published in the newspaper the next day was, “Songs of the Ainu people: Performance, Heartrending.” The reporter had used a mere thirty characters from a total of about 400 characters to describe the concert, writing, “At the end, artists performed and danced to the mukkuri (Ainu mouth harp) together.” While we did sing and dance, it is strange that such a supposedly seasoned reporter would write in such a shallow manner. Wouldn’t it have been much better if the journalist had simply written about what they felt and experienced through the performance, rather than listing audience names and comments about how it was rare to see all the performers gathered together?

There is a rule at the Hokkaido Shimbun newspaper where any reporting related to the Ainu must use the term, “minzoku” (“ethnic group”). Apparently, referring to us simply as “Ainu” is rude. For example, news articles that mention me should introduce me as an “Ainu-minzoku tonkori player.” It feels awkward for me living in a rural community to see such exaggerated words in the newspaper. After all, we don’t use the term “Yamato-minzoku singer” (to refer to a Japanese singer). Because the newspaper has decided to label us as “Ainu-minzoku,” they have chosen to have uniform reporting as it relates to ethnic groups.

The word “Indigenous” was also discussed by the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations, which met over the course of a decade in the 1990s. We should create a pathway to obtain collective rights using the plural “Indigenous peoples” rather than the singular “indigenous people” (which is limited to individual rights.) After all, we are an ethnic community, but it is difficult to exist as one unified group with the ongoing pressure of assimilation policies. We want to be recognized as an ethnic group and we want to regain our ethnic identity. For this to happen, we want the government to return our land and fishing rights, which we did not give up. We have lost our ethnic coherence and vitality due to pressures from assimilation. This is why many Indigenous peoples have appealed to their governments to reflect upon the situation and improve the environment. As Indigenous peoples around the world raised their voices, the Japanese government could no longer make lame excuses that there were no Ainu in Japan, and instead only the Utari people. This increasing pressure pushed the Japanese government to finally recognize Ainu as an Indigenous people. Even the enactment of the Ainu New Law has been criticized as insufficient because Ainu exercise of basic rights as Indigenous people are limited to culture, with a very narrow definition of culture. In reality, we Ainu have not yet exercised our rights as a collective Indigenous people, even while the newspaper insists on referring to us as “Minzoku” (ethnic group).

Even while some areas assert their fishing rights, it is not necessarily the case that the Ainu as a whole want to exercise their rights, including autonomy. On December 10, 1992, in his commemorative speech at the United Nations General Assembly “International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples,” Nomura Giichi, Executive Director of the Hokkaido Utari Association, said that we Ainu had no intention to declare independence or secede from Japan, but would demand the right of ethnic self-determination. However, after Nomura’s sudden resignation and the appointment of an LDP-affiliated executive director in 1996, the Act on the Promotion of Ainu Culture, and Dissemination and Enlightenment of Knowledge about Ainu Tradition, etc. (Act for the Promotion of the Ainu Culture) was suddenly enacted. This law was limited to promoting Ainu culture, and differed notably from what Ainu people had been campaigning for until then. The Ainu leadership accepted a culture-only law rather than taking on the daunting task of how to achieve self-determination. During Nomura’s time as executive director, there was an attempt to bring Ainu together, but now I sense that the individuality of each region with a significant Ainu community has become more pronounced. Though it may appear as if the Ainu have been diminished and our assertion of Indigenous rights have been eclipsed, this is not the case. Here lies the secret to Ainu-style survival. The Ainu are a people who once abandoned the Ainu name and the Ainu language in order to survive. While dissatisfied, we accepted the new law without making any waves. And we are now taking back the Ainu culture that our ancestors once shunned, and creating a path to consider the next steps. We will no doubt continue to pass on the legacy of our ancestors while living strongly and embracing change.

Note: English translation supervised by ann-elise lewallen, Associate Professor of Pacific and Asian Studies at the University of Victoria.

Translated from “Minzoku to yobarete (Calling Us Minzoku, an Ethnic Group),” Shiso, December 2022, pp. 2–6. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [June 2023]

Keywords

- Oki

- musician

- Oki Dub Ainu Band

- Ainu

- Ainu language

- Ainu culture

- Ainu music

- Ainu dance

- utari

- minzoku

- ethnic group

- Ainu-minzoku

- indigenous populations

- Ainu boom

- Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park

- Upopoy

- Ainu Festival

- Foundation for Ainu Culture

- Ainu Music Festival

- Mitsuishi Ainu Association

- tonkori

- mukkuri

- Hokkaido Shimbun newspaper

- Hokkaido Utari Association

- Nomura Giichi

- Act for the Promotion of the Ainu Culture