Co-creation with Asia in the era of “business and human rights (BHR)”

The Biden administration has set out to return to a path of international cooperation. Within this, the strategy was to counter China by building a network of encirclement with “like-minded” countries that shared “values” such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which Biden launched in Tokyo in May 2022, is a key component of this strategy. One of the main value axes in this is human rights, or “business and human rights (BHR).”

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

The unipolar era in which Japan unilaterally “chose” its Asian partners is over, and we are entering a multipolar era in Asia. How should Japan deal with this evolving dynamism in order to be “chosen” as a trusted partner? This paper will discuss viable strategies in the “age of values,” with a focus on “business and human rights (BHR).”

Goto Kenta, Professor, Faculty of Economics, Kansai University

The era of connectivity

The 21st century is the era of connectivity. Increased mobility of goods, people, capital, and information has deepened connections across borders. Most goods and services are now produced in global value chains (GVCs), connecting various types of companies in countries at different income levels. GVCs have developed most extensively in Asia, where these complex intra and inter-firm organizational forms have elevated it to the “factory of the world.” In recent years, however, Asia has become much more than just the “factory.” It has also emerged as the world’s “market,” “investor,” and “innovator.” Its global economic influence is now on par with regions such as North America and Europe.

Looking back at Asia in the post-World War II era, we see a Japan which growth has always been achieved in a global context. Export-led industrialization through processing trade, in which Japan was dependent on natural resource imports from Asia, has put it on a rapid growth trajectory in the 1960s. This has contributed to transforming and upgrading Japan’s economic structure. In the process, however, some of the domestic industrial sectors that lost their international comparative advantages were transferred to neighboring countries through trade and investment, inducing development and structural changes in these countries as well.

This is the so-called “flying-geese” model of economic development. As discussed in the 1993 World Bank report, The East Asian Miracle, postwar economic performance in Asia was far beyond the global average, and Japan has played the leading role in this.

Japan’s position in Asia, however, started to shift significantly, as the Japan-led “flying-geese” model begun to erode in the 21st century. Countries in Asia have become more competitive and relevant in the global economy, and as a result businesses from those other than Japan started to influence the shaping of the Asian economic order as well. As such, it has become imperative for Japan to respond and adopt to this evolving context with a new strategy (Goto, 2019).

This paper will provide an overview of the changes regarding Japan’s position in the regional economy by focusing on GVCs, which underpin contemporary economic dynamism in Asia. Given the transformation in regional economic order from “Japan’s unipolar era” to “Asia’s multipolar era,” how should Japan relate and co-create with Asia? We will approach this question by looking at “values,” with a focus on human rights. Human rights, or “business and human rights (BHR),” have become a key issue influencing how GVCs will be organized particularly in the 2020s and beyond. Much of the background of this paper is based on my book Ajia-keizai towa Nanika (What is the Asian economy?) (2019, Chuko Shinsho).

From internationalization to GVCs

Japan’s postwar economic development unfolded through its connections with the world economy. In the 1950s, Japan’s main exports were predominantly labor-intensive industry based, producing products such as the “one-dollar blouse” for the US market. Those connections with the US and European markets provided access to advanced technologies and knowledge, contributing significantly to Japan’s industrialization.

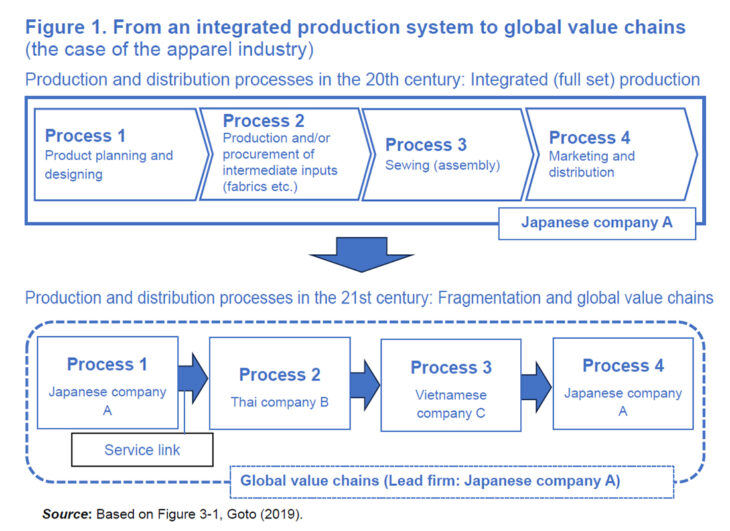

As Japan’s economic structure became more sophisticated, companies actively adopted an internationalization strategy to manufacture their products overseas. This was basically a “multidomestic strategy” in which a full set of domestic production processes was deployed overseas. Around the 1990s, however, there was a shift from this integrated strategy towards a network-based one, connecting different companies in various countries through complex investments and inter-firm relationships. This shift from integration to disintegration of production processes is what characterizes the era of GVCs.

Whether it’s apparel or smartphones, the production flow consists of many different processes and functions. Some of the processes may be labor-intensive, such as assembly, while others can be capital-intensive. There might also be functions that are knowledge-intensive, such as marketing and designing. GVC is rational because it allows businesses to optimize overall efficiency by slicing up the integrated production processes with different degrees of factor intensities, and relocate them to companies in locations that are endowed with suitable factors of production, enabling them to capitalize on their international comparative advantages (fragmentation).

Figure 1 describes the apparel value chain. As discussed, the planning and marketing related functions such as “Process 1” and “Process 4” tend to be of high knowledge-intensity, and therefore developed countries like Japan typically have international comparative advantages in these. On the other hand, “Process 2,” which produces fabrics, is a capital-intensive process, suitable for middle-income countries such as China and Thailand. Countries with abundant labor such as Vietnam and Cambodia tend to exhibit strong comparative advantages in “Process 3,” which is highly labor intensive. The Japanese company A in Figure 1 is the most important actor in the entire value chain as they control the entry of firms into the value chain. They also set key parameters related to how production and distribution should take place, determining the organization of the value chain. These companies are called “lead firms.” Lead firms normally have advanced technological and branding capabilities, and are in a superior position over other companies in the value chain.

From Japan’s unipolar era to Asia’s multipolar era

In the 21st century, Japan’s relative position in the regional economy has declined significantly. GVCs in Asia used to be organized mostly by Japanese lead firms because of their overwhelming technological superiorities. However, new actors from countries other than Japan have also emerged as lead firms coordinating value chains in Asia. There are multiple factors behind this, one of which is the change in “product architecture” from “integral” to “modular.”

“Product architecture” is the basic design plan regarding product attributes and production processes. There are two major types of this. First, there is the “integral product architecture,” which aims for overall optimization by coordinating the technical specifications of parts and components for a particular product. The other type is the “modular product architecture,” in which the interface of parts and components are standardized, and as such enable production of different products by combining them flexibly according to common rules. In the 1990s, the product architecture began to shift from integral to modular in many sectors, particularly in the electronics industry, which was once dominated by Japanese companies (Kawakami and Goto, 2018).

When Japan was leading many of the globalized industries, product architecture was primarily integral. There were close collaborations between manufacturers of final products such as electronics companies and suppliers of parts and components, in which new technologies and specialized (relationship-specific) inputs were jointly developed. As such, there were strong interdependence and complementarity between the components, making it difficult to replace and substitute them with others. Japanese companies developed and accumulated technology and knowledge internally through this process.

Asian companies with low levels of technological accumulation were unable to compete with the Japanese, and were integrated into GVCs coordinated by Japanese lead firms. However, as modularization progressed, substitutability of parts increased, making it easier to externalize and outsource specific processes and functions. This allowed Asian companies to focus on a specific modularized processes, providing them new opportunities to enter into GVCs and upgrade. This has led to substantial changes in the power relationship between different companies in those GVCs, weakening the relative positions of Japanese companies.

A typical example of this shift can be seen in the electric vehicle (EV) industry. While conventional vehicles equipped with internal combustion engines are characterized by an integral architecture, EVs are overwhelmingly modular. As a result, companies that previously were not involved in the automobile industry are suddenly entering the EV industry. VinFast of Vietnam is a typical example, which is a subsidiary of Vingroup, which main area of business used to be in real estate. It was founded in 2017, and released its first EV on the market in 2021. In August 2023, it was listed on the NASDAQ in the US, attracting great attention.

In addition to these changes in the technological base, the expansion of each country’s domestic market has also raised the position of Asian companies. The unipolar era in which Japan was able to lead the formation of Asia’s economic order by unilaterally choosing its Asian partners has ended, and we have entered an Asian multipolar era. Japan now needs to be “chosen” by Asian businesses as a trusted and reliable partner. Given this, how should Japan interact with Asia? This has become one of Japan’s most relevant and pressing questions today.

GVC in an era of “division”

In the 2020s, a new factor has emerged to influence the dynamics of GVCs. Politics began to come to the fore. The friction between the US and China, which became progressively apparent in the 2010s, intensified and manifested as trade conflicts around 2019. This led to some sort of an economic and political division, which effects propagated beyond the US-China bilateral relationship across Asia, including Japan. GVCs in Asia, which were closely connected to both the US and China, were also affected, having repercussions on the local economies of each of the countries. Connectivity based on mutual interdependence in GVCs has underlain regional economic growth as well as innovation. The division between the US and China led to some disruptions in value chains, and possible decoupling between the two economies has been among the topics of discussions since.

The coronavirus pandemic that broke out at the end of 2019 also disrupted GVCs due to measures taken to prevent the spread of the disease. However, as the pandemic became more or less under control, ushering the world into the post-corona era, the risks of disconnection did not disappear. On the contrary, it became more acute over export controls on strategic goods such as semiconductors in the context of national security and technological hegemony. The competitive strategy in Asia’s open and stable regional political and economic environment was to pursue efficiency based solely on economic variables. However, such an approach seems to have reached a certain limit.

Non-economic variables such as values including democracy and sustainability have begun to play major roles in the formulation of GVCs. For example, concerns on forced labor involvement in the production of cotton products in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region prompted the US to impose import restrictions. As a result, the apparel value chains for the US market were forced to undergo some level of reorganization. The paper will next focus on human rights as a major business variable, and examine the challenges and possibilities for future GVC development in the context of BHR.

BHR and GVC

One of the core issues of Japan’s current trade policy is human rights. When the second Kishida administration was launched in November 2021, the post of Special Advisor to the Prime Minister in charge of international human rights issues was created. Human rights divisions were also established in the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Behind these movements is the global geopolitical dynamism mentioned above.

Prior to the inauguration of the Kishida administration, the Biden administration came into office in the US in January 2021, renouncing the inward-looking policies of the previous administration and returning to a path of international cooperation. On the other hand, in response to the intensifying conflict with China, the US has strengthened its solidarity with “like-minded countries” that share values such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. The strategy was to counter China by encircling and isolating it. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) launched by the Biden administration embodies exactly this, and one of the value axes in this strategy is human rights.

BHR is an issue both old and new. Its origin dates to the 1970s, when the influence of multinational corporations was growing, particularly on developing countries. As the Cold War ended and globalization reached its peak in the 1990s, calls for companies to act responsibly grew stronger. These eventually led to the unanimous endorsement of The Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2011, which is regarded the most authoritative guidelines on BHR.

The responsibility to protect and promote human rights have traditionally been considered to rest upon the State. However, the UNGP clearly states that businesses, in addition to the State, also have a responsibility to respect human rights. While the UNGP remains essentially voluntary in nature, laws and regulations have been drafted and enacted in Europe and the US that require businesses to respect human rights in GVCs, particularly by implementing due diligence (Goto, 2022a). Due diligence refers to the continuous process of identifying and assessing potential and actual human rights and other risks, integrating findings and provide remedy, tracking effectiveness of measures taken, and reporting the processes to wide-ranging stakeholders. For example, in Germany, the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG) came into effect in January 2023, making human rights and environmental due diligence mandatory. Similar laws are in place in France and the UK, and an EU directive is now being discussed. Doing business in these countries require businesses to look at non-economic variables such as human rights in addition to the traditional economic variables such as quality and productivity. Businesses in Asia, including Japan, are facing an entirely new type of challenge in which they must organize and manage GVCs in a way that align competitiveness and good human rights practices.

GVC is often discussed in relation to technological hegemony and national security, as discussed earlier. Many Asian businesses and their workers, however, make their living through connections with value chains of apparel, food, and consumer electronics and machinery, which are distinct from these sensitive and strategic sectors. How can we advance together in Asia in the “era of values,” which have started to also affect these “ordinary” value chains? I trust that Japan can make important contributions in this.

Towards a new co-creative relationship between Japan and Asia

The main challenge of aligning competitiveness and good human rights practices in the era of GVCs has to do with the fact that it must be in place throughout the value chain, which typically involves highly heterogeneous groups of actors. Asia is very diverse in terms of economic and political systems, as are the realities and reactions regarding human rights issues, including labor rights. When the guidelines and regulations mentioned above become more widespread and substantial in GVCs in Asia in the future, it is highly likely that various issues will arise. This is where Japan should come in as a trusted partner. It can actively play a role in sharing of the good practices, or the “tacit knowledge,” that are embedded in its business practices, which often evolve from purely profit seeking motivation while being highly compatible with good human rights practices.

There is no doubt that the UNGP and legal frameworks in Europe and the US are powerful tools to ensure good corporate behavior in respecting human rights. Such an approach with enforcement is called a “de-jure” approach. On the other hand, “desirable” business practices can also reside in purely competitive strategies. Because these business strategies emerge from profit-seeking motivation even in the absence of enforceable rules, it is highly self-enforcing. This is called the “de-facto” approach (Goto, 2022b).

The author has observed many sustainable business practices embedded as tacit knowledge, including those in relation to human rights, at Japanese companies operating both in and outside of Japan. For companies in developing countries, the biggest advantage in connecting to GVCs is the access to advanced technology and knowledge. Some of them are explicit, but some are intrinsically tacit. Both types are important, and Japanese businesses are well endowed with tacit knowledge. The so-called “Japanese-style management” may include practices that are outdated in the global and modular era. However, there still remain a lot of practical knowledge in Japanese companies in the form of tacit knowledge that is useful in the era of BHR. For example, emphasizing stability in inter-firm and employment relationships, or creating and valuing informal dialogue opportunities between internal and external stakeholders can be such win-win practices (Goto and Arai, 2018, Goto 2022b).

Japan’s experience can be useful in addressing the new challenges unfolding in the “era of values.” The first step is to discover together with Asian partners the tacit knowledge rooted in Japanese practices and reevaluate them in the context of BHR. In many cases, it may be difficult for Japanese businesses to see the value of their own practices, and may be easier identified by Asian partners. In order for Japan’s practices to be useful in Asia as sustainable competitive strategies, the process of adaptation given the local social and economic context is crucial. This will only be possible if Japan and Asia engage in constructive dialogue on an equal footing and move forward with an attitude of mutual learning. Such co-creative relationships will be the basis of a sustainable future for Japan and Asia.

References:

Kawakami Momoko and Goto Kenta, 2018. “Factory Asia: global value chains and local firm development” Endo Tamaki, Ito Asei, Oizumi Keiichiro, Goto Kenta (eds.) “Contemporary Asian Economy: Learning about the Asian century,” Yuhikaku, pp. 72-93.

Goto Kenta, 2019. “What is the Asian Economy? Its Growth Dynamism and Japan’s Future” (Chuoko Shinsho) Chuokoron-Shinsha.

Goto Kenta. 2022a. “‘Business and human rights in the era of globalization” “Asia-Pacific and Kansai – Kansai Economic White Paper <2022>” Asia-Pacific Institute of Research, pp. 44-51.

Goto Kenta 2022b. “Responsible Supply Chains in Asia: The Case of Japan’s Electronics Industry” (Japanese version) International Labour Office, Tokyo: ILO.

Goto, Kenta and Yukiko Arai. 2018. More and Better Jobs through Socially Responsible Labour and Business Practices in the Electronics Sector of Viet Nam. International Labour Office, Geneva: ILO.

Translated from “‘Bijinesu to Jinken’ jidai no Ajia tono Kyoso (Co-creation with Asia in the era of ‘business and human rights’),” Voice, November 2023, pp. 82–89. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [December 2023]

Keywords

- Goto Kenta

- Kansai University

- economy

- business

- values

- global value chains

- GVCs

- economic development

- flying-geese model

- Japan’s unipolar era

- Asia’s multipolar era

- apparel industry

- electric vehicle industry

- product architecture

- integral

- modular

- modularization

- politics

- democracy

- sustainability

- human rights

- freedom

- rule of law

- Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF)

- Principles on Business and Human Rights

- Japanese-style management

- mutual learning

- co-creation