Making Use of an Empty House in the Countryside: The Soja Art House Project

Isoyama Tomoyuki, Business Journalist, President, Economic Strategy Initiative

You have inherited a house in your home town from your parents. It’s been empty for a while, but it’s not easy to knock down a house so full of family memories. This is an issue faced by many Japanese people who once left their home town in the countryside to live in the city. A survey in 2013 recorded 8.2 million empty houses across Japan. Since there are a 60.63 million houses in Japan, empty houses account for 13.5% of the total. The low birthrate is one factor, but there are many old houses across Japan which are empty, but which the owners are reluctant to demolish.

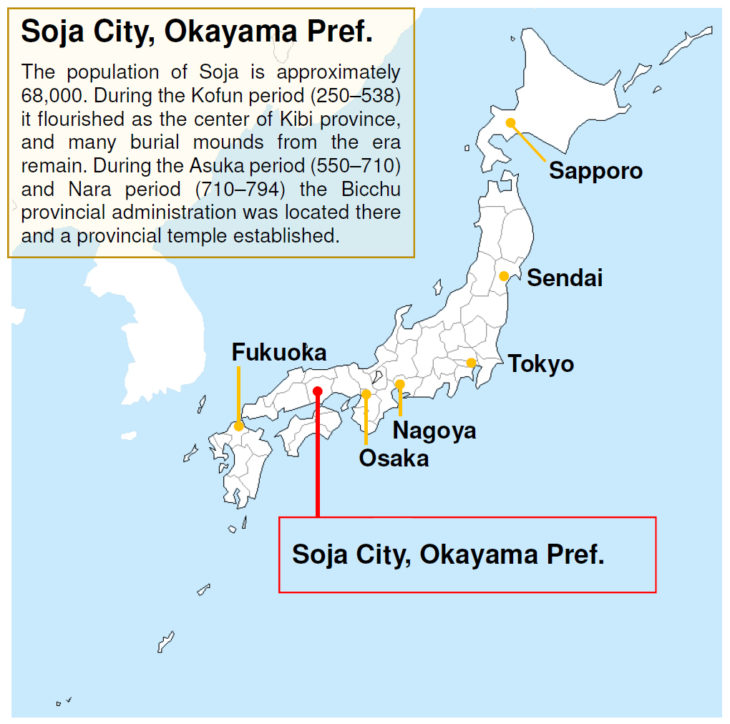

Ikenoue Shinpei, who lives in Isehara City in Kanagawa Prefecture, is the owner of such a house. It was originally built in the same country and reconstructed in Soja City, Okayama Prefecture, by his great-grandfather during the Taisho period (1912–1926). When his grandmother died some twenty years ago, it was left empty. Although Ikenoue was born in this house, his family moved for his father’s job, and he was raised in Kyoto then lived and worked in East Japan. For a while the house was lent to an NGO group for people with disabilities, but following that it was left to fall into ruin.

The Ikenoue residence was once used by Soja’s first mayor (then town mayor), and is an example of traditional Japanese architecture: a study and central living space facing a garden containing large decorative rocks, and a earthen wall encompassing the residence. Behind the house there was also a storehouse and tea house. “I thought about tearing it down,” says Ikenoue, “but I was told that just demolishing it would cost around 10 million yen, so hesitated.”

At that time, he was introduced to architect and artist Matsumoto Gotaro.

In 2006 Matsumoto had closed his architectural practice and moved to the town of Wake in east Okayama Prefecture where he renovated an old house by himself, turning it into an atelier where he could work on his painting and sculpture. When Matsumoto saw the Ikenoue residence, he suggested completely renovating it and turning it into an art house where people could gather. That was in 2014. He would be assisted in the project by his close collaborator Korenaga Kazuhiro, a modern artist who works with silk screen prints and other media.

In return for taking on the renovation in full, Matsumoto would not be charged any rent, and Ikenoue also agreed to cover part of the cost of materials used. “It ended up costing less than demolishing the house,” says Ikenoue. The contract period was a minimum ten years; the agreement didn’t end with the renovation but was a long-term commitment for it to be used as an art house.

“Matsumoto and Korenaga and their art works played a role to provide a catalyst which might develop something unexected. Even more important is the communication between the people who come to see them. They wanted to make a place where people could meet, and they caused things to happen,” Ikenoue recalls.

It needed a bar counter

The major renovation started in 2015 and was more or less finished by the summer of 2016.

“The wood carvings in the window by the tokonoma alcove were done with incredible attention to detail. The instant I saw them I thought what a waste it would be to destroy them,” says Matsumoto. We replaced the stairs, removed walls to make the rooms bigger, and carefully strengthened the house against earthquakes. Unfortunately the tea house had deteriorated and had to be demolished, but we reinforced the storehouse to stop it from leaning.

“When I dug up the garden I found traces of a fine lake, and stones arranged to make a waterfall,” says Matsumoto enthusiastically. He continued to work on the project without any outside help. Although he has managed to make a space adequate for exhibitions, the project is far from completely finished.

At the main entrance, where there used to be an earthen floor, Ikenoue has laid a wooden floor and installed a long wooden counter. Korenaga, who was responsible for planning the renovation, explains:

“It is a gallery where you can learn about the artists themselves. If it isn’t comfortable as a space, people won’t come. That’s why, first of all, we needed a bar.”

The idea is for the artists to hold solo exhibitions at the Ikenoue residence, and the art lovers who come to see the exhibition to enjoy drinking at the bar.

“It has become one of Soja’s culture hubs,” says Korenaga with a smile.

Korenaga has taken on the organization of the Okayama prefecture sponsored “Town Arts Management Project,” and has a range of personal contacts among local officials and artists. He is making full use of those connections.

From November 11 to 13, 2016, the former Ikenoue residence, newly christened the Soja Art House, held its first art exhibition, named “Iron and Enoki Chu.” It featured a number of art pieces by Enoki Chu, known for his work using scrap iron. Matsumoto has been friends with Inoki since their youth, and Korenaga has also known him for many years. Despite them only publicizing the exhibition via fliers issued by Soja, over 350 people visited the exhibition.

In fact, the reason they chose iron as the theme for the exhibition wasn’t just because they knew the artist Inoki.

“Soja is the birthplace of iron culture,” says Korenaga. The Kibi region of Soja was home to the ancient tatara method of iron-making. According to legend, iron-making was transmitted to Kibi by the demon Ura, and the iron-making town was inhabited by blacksmiths and iron-casters who were his descendants. There is a theory that the demons vanquished by the famous folk hero Momotaro were actually the tatara iron-makers of Kibi. That’s why iron, with its deep links to Soja, was chosen as the theme for the Art House’s first exhibition.

Workshops were also held before and after the exhibition — art events that were given the title, “Demon, Iron, Loyalty: A Project to Examine Prehistory to Modernity through Iron.”

Linked to this was an October event held in a Soja park to faithfully recreate the sixth-century tatara method of iron-making. The recreation of tatara iron-making was led by Hayashi Masami whose ancestors were iron-casters, and who has been working to revive genuine tatara culture since completing his career at a financial institution. At the same time, for the last sixteen years he has been running a private night school in Soja, called “Kinojo-Juku” (demon castle night school). He has organized lectures by artists and others invited from all over Japan, a network of artist contacts that became an important resource for Soja as an art hub.

“It was painful to watch the house crumbling away, so this really is fantastic,” says Ikenoue smiling. Ikenoue Yoko, who is part of the family still living in Soja, is also pleased. “The house has been brought back to life without losing its atmosphere of elegance,” she says. “I hope it will lead to a revitalization of this area as a place where people can meet and be active.”

This house was home to generations of the Ikenoue family, and was filled with laughter. Now it has been turned into a beautiful work of art, and reborn as a place for even more people to experience happiness.

What might the future bring for the Art House? Will it become an art hub for Soja, a place where artists gather, and play a role in the revitalization of the area? Let’s watch and find out.

Translated from “Kokyo no akiya wo katsuyo — Soja aato housu no chosen (Making Use of an Empty House in the Countryside: The Soja Art House Project),” Wedge, February 2017, pp. 76-78. (Courtesy of WEDGE Inc.) [February 2017]