Shinkokinshu: An Anthology for Our Times

Portrait of the Emperor Go-Toba (1180-1239)

Source: Via Wikipedia, Public Domain

Most Japanese newspapers carry a weekly column of waka (poems in 31 syllables) and haiku (poems in 17 syllables) submitted by readers. This journalistic feature indicates to what extent poetry permeates the everyday lives of the Japanese.

Similarly, at the beginning of each year the Emperor holds a competition for waka composed on a topic of his choice, and the people of Japan submit their poems.

These modern poetic practices have their roots in the long tradition of court waka. Superior poems produced at the Japanese court over the centuries were collected in a series of anthologies compiled by imperial command. One of these, the Shin Kokin Waka Shu (New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poetry, usually abbreviated to Shinkokinshu), is considered by many to represent the summit of the art, and has the unusual distinction of having been edited personally by the emperor who commanded the creation of the anthology. This year [2005] marks the eight-hundredth anniversary since the compilation of this magnificent and unique collection.

The novelist Maruya Saiichi [1925-2012] offers his words of congratulation.

On the 26th day of the third month (April 17) of 1205 a celebration was held to mark completion of the Shinkokinshu. As a matter of fact, the collection continued to be revised for some years afterwards, but if, forgetting this for the moment, we accept 1205 as the date of completion, the Shinkokinshu marks its eight-hundredth anniversary this year [2005]. The event is truly something to celebrate. This anthology represents the very pinnacle of the art of Japanese literature and as such is the highest flowering of Japanese literature. The great scholar of literature Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), after declaring that the Shinkokinshu was the supreme anthology of Japanese poetry, went so far as to stigmatize anyone who did not appreciate the masterpieces among the poems of the collections as an insensitive lout with no understanding of poetic beauty. I would add that the Shinkokinshu exercised a decisive influence on other masterpieces of the Japanese tradition, including Heike monogatari (The Tale of the Heike), the noh plays of Zeami Motokiyo, and the haiku of Basho.

Heike monogatari, believed to have been committed to writing in the thirteenth century, is an epic poem describing the rise and fall of the Heike clan in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Although it recounts the turbulence of war, it is infused with a Buddhist sense of sadness, a masterpiece comparable to Homer’s. Noh, a refined and elegant form of theater, originated in the fourteenth century and was perfected in the fifteenth century by Zeami. The Irish poet and playwright W. B. Yeats was inspired by noh to write such plays as At the Hawk’s Well. Basho, the great poet of the haiku, was the author of Oku no hosomichi (The Narrow Road to Oku), which combines haiku and prose in the form of a travel diary. This work has been translated by the celebrated Mexican poet Octavio Paz. As these examples suggest, the imperial anthology gave birth to literary works of the first importance, including the epic, drama, poetry, and travel diaries.

What Are Imperial Anthologies?

Imperial anthologies were collections of superior waka compiled by imperial command. Originally, such compilations were made in imitation of Chinese court practices, but they were far more numerous, reaching a total of twenty-one anthologies. These collections were a mechanism for displaying the cultural power of the court, and this of course could be used to assert political power.

The first characteristic of the collections was an insistence on orthodoxy. Superior poems were chosen both from the classical canon and recent works and were arranged as a rule in linear fashion with no duplication. The compilers of the various anthologies, though deeply respectful of precedents in the topics of the poems, the prefaces, the subject categories, and the arrangement within the categories, devoted great attention to obtaining new effects. They evidently wished it to be believed that the court represented the mainstream of the culture of the time, and this of course served at the same time as proof of the court’s legitimacy.

Second, the majority of recent poems included in the anthologies were written by members of the aristocracy, proof that the court boasted excellent poets.

Third, the anthologies demonstrated that the court also harbored capable critics. It was incumbent on the compilers (critics who were poets themselves and possessed both a discerning eye and extensive knowledge) to choose the best poems from the past and the present. Their choices of poems from the past were especially important. They were expected to find poems that differed from those chosen by previous anthologies, works that possessed some connection with the poetic style of their own time and which were congruent with new literary taste. By so doing, they could convince the world that the court was not only in step with current times but also capable of giving new life to tradition.

Fourth, because having one’s poem included in the anthologies conferred a great deal of prestige, they functioned as a system for bestowing honors. The anthologies were arranged starting with poems by the present or retired emperors and empresses, followed by poems by high-ranking officials and nobles, and going on down to poems by prostitutes; anthologies of poetry thus became a court ceremonial based on word play.

Fifth, the anthologies functioned as journalism that disseminated and advertised the court culture. Manuscript copies were repeatedly made, and the literary sensitivity they embodied came to dominate all of Japanese civilization. The fondness of the Japanese people for natural scenery and the changes in the seasons, as well as their manner of courtship, were learned from the imperial anthologies.

In this way, court poetry (the best of which was included in the imperial anthologies) formed the foundation of Japanese culture. Their decisive pattern colors even the customs of present day society. At the beginning of each year a call goes out for waka to be composed on a topic prescribed by the emperor, and a literary competition under the sponsorship of the court is held. The emperor and empress attend this ceremonial (known as yoshuku, or “advance celebration”) and the successful poems are read aloud. On a more popular level, many of the names adopted by professional dancers and sumo wrestlers are taken from court poetry. Even today, Japanese live with court poetry as their canon. In this context, it bears repeating that the most beautiful of the twenty-one imperial anthologies is the Shinkokinshu.

Many scholars have studied the Shinkokinshu, but among modern scholars Kojima Yoshio [1901-1989] achieved the most remarkable results. Kojima demonstrated in his Shinkokin waka shu no kenkyu zokuhen (A Study of the Shinkokin Waka Shu, Volume Two) that the Shinkokinshu was unlike other imperial anthologies in that the Retired Emperor Gotoba, who commanded the compilation, actually selected the poems himself. The others named as compilers— Minamoto no Michitomo, Fujiwara no Ariie, Fujiwara no Teika, and Fujiwara no Masatsune—were no more than his assistants. It is true that some earlier scholars had come to the conclusion that the Shinkokinshu was compiled by the Retired Emperor himself, but for a variety of reasons this had never become the prevailing opinion.

First of all, it was customary for the compilers, not the emperor, to edit imperial anthologies (although there were instances of an emperor examining the final manuscript and making partial corrections). This was true of all seven anthologies that preceded the Shinkokinshu, and both prefaces of the Shinkokinshu (one in Chinese, the other in Japanese) record the name of five compilers. Second, one of the nominal compilers, Fujiwara no Teika, was a renowned poet, and for generations his descendants proudly exercised authority over the art of poetry. Teika’s fame not only lasted until the Meiji Restoration (1868) but also remains untarnished to this day. This led modern scholars to believe that Teika was the real editor in chief and not the Retired Emperor Gotoba. Another factor contributed to their unwillingness to admit Gotoba was the compiler: it seems certain that nineteenth-century Western literary thought, Romanticism, and the concept of democracy provided the psychological backdrop to their conviction Gotoba was not the compiler. Under this European influence, they displayed feelings of reverence for artists and a reluctance to admit that an emperor might have literary ability. For one thing, there was no example in the history of Western literature of a ruler who possessed great literary talent. Again, the ability as a poet of the Emperor Meiji had been used for purposes of propaganda by the Meiji government, and this adversely affected the judgment of scholars, who found Meiji’s poems unimpressive, though they were certainly numerous. These two factors no doubt strongly influenced scholarly opinion concerning Gotoba’s literary efforts.

If, however, we examine Teika’s diary and other sources, it becomes absolutely clear that virtually every aspect of the creation of the Shinkokinshu was personally supervised by the Retired Emperor Gotoba—the selection of the poems, the assignment to categories, the order of arrangement, and the style of the headnotes and prefaces. The Shinkokinshu was the emperor’s work, a work highly imprinted with the authority of the imperial editor in chief. Kojima’s researches, which combined rigorous empirical methodology and a refined literary sensibility, established this irrefutably.

The Waka of the Retired Emperor

It goes without saying that the Retired Emperor Gotoba was a great poet. His poems are rich in poetic sentiment and display the easy mastery of technique characteristic of the Shinkokinshu as a whole.

Here are three representative examples.

miwataseba

yamamoto kasumu

Minase-gawa

yube wa aki to

nani omoiken

When I gaze far off

The mountain slopes are misery.

Minase River—

Why did I ever suppose

Evenings were best in autumn?

nohara yori

tsuyu no yukari wo

tazune kite

waga koromode ni

akikaze zo fuku

From fields and meadows

The autumn wind comes searching

For the dew and for

Something rather like the dew—

How it blows into my sleeves!

omoiizuru

oritaku shiba no

yukikeburi

musebu mo ureshi

wasuregatami ni

When, thinking of her,

I break kindling for the fire,

I choke in evening smoke,

But the smoke also brings joy—

A memento of the dead.

(Translated for this article by

Donald Keene)

What sets these poems apart is their relaxed, almost casual tone—a quality one would never find in poems composed by a professional poet (Teika, for example). Gotoba’s poems are bold and open-hearted, yet avoid ostentation. Although they are colored by an inborn imperial tone, there is not the slightest hint of the specious ennui so commonly found in poems by other emperors. They incorporate popular kouta (song) forms, yet convey an extremely high level of refinement. Even when they toy with allusion, the poems always manage to seem fresh and original. No wonder Teika acknowledged their superiority. If one had to select the ten greatest Japanese poets of all time, it would be difficult not to include Gotoba in their ranks.

Gotoba also possessed outstanding critical abilities, as is clearly evidenced by Gotoba no in gokuden (The Former Emperor Gotoba’s Secret Teachings), a treatise on poetry he wrote about the same time that he compiled the Shinkokinshu. His editorial skills, however, provide an even more important proof of his critical acumen. Some might think that compiling an anthology does not constitute an act of critical judgment. This may be true if the anthology is purely historical or merely follows established reputations or indulges in personal whims, but if its purpose is to contribute something to the tradition of the literary arts and to change the tastes of a civilization, the act of compiling an anthology of poetry becomes a splendid example of criticism. In such instances the personal taste and assertions of the poet-editor can change the course of literary history. Such anthologies exist in England today: Yeats’ The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, Michael Roberts’ The Faber Book of Modern Verse, and Auden’s The Oxford Book of Light Verse. Many others have attempted the feat, but none with more glorious success than the Shinkokinshu.

Origins of the Waka

As was true of poetry in other countries, the origins of the waka are to be found in incantations. Waka of celebration and of mourning were believed to possess magical properties that they retained even after the waka had become a form of greeting. Waka, originally simple and unsophisticated, were refined by the imperial court; in the process, they began to be composed for amusement and used as an instrument of social intercourse. By the Heian period (794–1185), a custom had arisen that required members of the aristocracy to write and send poems expressing amorous feelings to the objects of their desire, a process described in great detail in Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji). In writing her great work, Murasaki Shikibu invented a new prose style that made use of the rich treasure of court poetry that had accumulated by her time. In addition, the characters in the tale itself use poems to great effect in a variety of circumstances.

Stimulated in part by Genji, there were increasing efforts to raise the artistic level of the waka as a means of social inter- course. However, there were rivalries among the different families of professional poets. The conservative attitudes at this time of the Rokujo family of poets (including Fujiwara no Kiyosuke and Kenjo) were not to Gotoba’s liking. The young emperor much preferred the Mikohidari family (which included the father and son Fujiwara no Shunzei and Teika, as well as poets of the same traditions, Fujiwara no Ryokei and Jien). Their poetry appealed to him because of its symbolist, pictorial quality, its depth of feeling, and its freshness. The result was that the Rokujo family went into a decline, while the Mikohidari family occupied a dominant position in the world of poetry that lasted many years. The Shinkokinshu scholar Kojima Yoshio believed that Gotoba actually reconstituted the world of waka poetry even before he started to compile the Shinkokinshu. One can say that the Shinkokinshu consists of the products of the world of court poetry over which the Retired Emperor Gotoba presided along with the old poems that were intensely loved by poets belonging to that world. It is interesting to note that, among the contemporary poets who were included, Shunzei was represented by 72 poems, Teika by 46, Ryokei by 79, and Jien by 92, as compared with only 12 for Kiyosuke and 2 for Kenjo.

One might liken Gotoba as a literary organizer to Ezra Pound’s activities within the modernist literary movement in England and the United States during the twentieth century. Pound’s contributions to modernism were enormous, beginning with his discovery of Joyce and the help he gave him, and his editing of Eliot’s The Waste Land. Without Pound, modernist literature would have undoubtedly developed in a very different way. In short, both Gotoba and Pound changed the climate of literature.

One important reason for viewing Gotoba as a literary organizer is that, as Kojima pointed out, he completely changed the uta-awase, or poetry contest, which at that time was the basic mechanism for the “publication” of waka. In a poetry contest the participating poets were divided into two teams whose members criticized the poems presented by the other side, leading to a final decision by a judge as to which of the two sides had won. What began as a gentlemanly pastime gradually evolved into a merciless competition with an accompanying decline in sportsmanlike gentility. The judges, concentrating on exposing faults, carped over trivialities, rather like prosecuting attorneys. It was Shunzei who changed this situation by adopting a warm and sympathetic attitude when judging. Gotoba approved of this change, and the result was that he succeeded in creating of the poetry contest a cooperative entity characterized by literary forbearance and generosity. New styles were recognized and encouraged, making an unhasty development possible. In other words, changing and showing respect for the social nature of the poetry contests made it possible to elevate the waka, an instrument of social intercourse, to a high level of artistry.

This phenomenon brings to mind Yamazaki Masakazu’s Shako suru ningen (People in Society). I learned a great deal from this work, which forced me to reexamine my ideas on such subjects as the necessity for politicians to be consummate masters of social intercourse. I was particularly struck by Yamazaki’s theory that there has always been an “other” culture that provided a model for the social intercourse that is the foundation of human relations. In the case of the social world of the Renaissance or the court salons of seventeenth century France, the models were the classical cultures of Greece and Rome and the medieval romances. In the case of the social groups of the Muromachi and Momoyama periods, it was the aesthetics of the Heian period and of China. These “other” cultures were images that served to clarify the object of their vague yearnings.

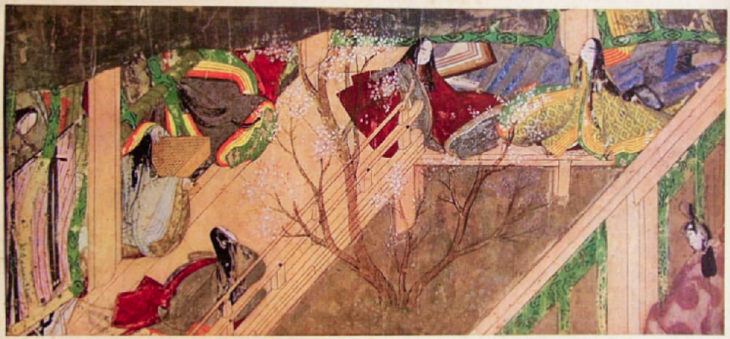

A scene of the Chapter “Takekawa “(Bamboo River) of Illustrated handscroll of Tale of Genji

Source: Via Wikipedia, Public Domain

The Shinkokinshu was a thirteenth-century “modernist” work that came into being by creating an awareness of the waka as occasional verse—poetry for social intercourse and for greeting—and by then ripening and refining it. In this process The Tale of Genji was of the greatest relevance. Shunzei warned that it was shocking for anyone to compose poetry without having read Genji, and one scholar has counted no fewer than thirty-three poems in the Shinkokinshu that allude to the work (including “From fields and meadows”). Yamazaki, the critic and playwright, is correct in this respect too. He points out that, in this age of globalization, when the influence of nations is waning, social intercourse has become an increasingly important element in our ethics.

If this is the case, the relationship between court culture and popular culture, which we have conventionally considered rather tenuous, is actually far more acute and immediate than we have supposed. In fact, it seems certain that a reexamination of the Shinkokinshu, which may be the highest expression of court culture anywhere in the world, will again be a matter of urgency to modern man. The Retired Emperor Gotoba is a contemporary of ours.

Related articles in Discuss Japan

The World of the Japanese Newspaper Poetry Column

/archives/culture/pt20180629160350.html

Remembering Ooka Makoto, The Poet from Mount Fuji

/archives/culture/pt20170731131605.html

Haiku: “Sharing Makes Peace”

/archives/culture/pt20170417145754.html

Reprinted from The Japan Journal, August 2005 (Vol. 2 No.4), pp. 34-37.

Keywords

- Emperor Go-toba

- Shin kokin waka shu

- waka

- tanka

- haiku

- Maruya Saiichi

- Japanese anthology

- Heian

- Muromachi

- Momoyama

- Fujiwara no Shunzei

- Minamoto no Michitomo

- Fujiwara no Ariie

- Fujiwara no Teika

- Fujiwara no Masatsune

- Donald Keene

- Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji)

- Murasaki Shikibu